Arxiv:2005.14671V2 [Astro-Ph.EP] 30 Jun 2020 Tion Et Al

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Introduction to Astronomy from Darkness to Blazing Glory

Introduction to Astronomy From Darkness to Blazing Glory Published by JAS Educational Publications Copyright Pending 2010 JAS Educational Publications All rights reserved. Including the right of reproduction in whole or in part in any form. Second Edition Author: Jeffrey Wright Scott Photographs and Diagrams: Credit NASA, Jet Propulsion Laboratory, USGS, NOAA, Aames Research Center JAS Educational Publications 2601 Oakdale Road, H2 P.O. Box 197 Modesto California 95355 1-888-586-6252 Website: http://.Introastro.com Printing by Minuteman Press, Berkley, California ISBN 978-0-9827200-0-4 1 Introduction to Astronomy From Darkness to Blazing Glory The moon Titan is in the forefront with the moon Tethys behind it. These are two of many of Saturn’s moons Credit: Cassini Imaging Team, ISS, JPL, ESA, NASA 2 Introduction to Astronomy Contents in Brief Chapter 1: Astronomy Basics: Pages 1 – 6 Workbook Pages 1 - 2 Chapter 2: Time: Pages 7 - 10 Workbook Pages 3 - 4 Chapter 3: Solar System Overview: Pages 11 - 14 Workbook Pages 5 - 8 Chapter 4: Our Sun: Pages 15 - 20 Workbook Pages 9 - 16 Chapter 5: The Terrestrial Planets: Page 21 - 39 Workbook Pages 17 - 36 Mercury: Pages 22 - 23 Venus: Pages 24 - 25 Earth: Pages 25 - 34 Mars: Pages 34 - 39 Chapter 6: Outer, Dwarf and Exoplanets Pages: 41-54 Workbook Pages 37 - 48 Jupiter: Pages 41 - 42 Saturn: Pages 42 - 44 Uranus: Pages 44 - 45 Neptune: Pages 45 - 46 Dwarf Planets, Plutoids and Exoplanets: Pages 47 -54 3 Chapter 7: The Moons: Pages: 55 - 66 Workbook Pages 49 - 56 Chapter 8: Rocks and Ice: -

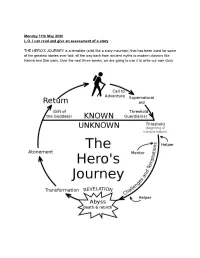

Monday 11Th May 2020 L.O. I Can Read and Give an Assessment of a Story

Monday 11th May 2020 L.O. I can read and give an assessment of a story THE HERO’S JOURNEY is a template (a bit like a story mountain) that has been used for some of the greatest stories ever told, all the way back from ancient myths to modern classics like Narnia and Star wars. Over the next three weeks, we are going to use it to write our own story One of the reasons STAR WARS is such a great movie is it because it follows the HERO’S JOURNEY model. Today, you are going to read / watch this version of the Hero’s journey and see how it fits into the format for our first act! The subtitles just refer to the stages of the story - don’t worry about them yet! Just read the story and if you have internet access look up / click on the clips on youtube. ORDINARY WORLD Luke Skywalker was a poor and humble boy who lived with his aunt and uncle in a scorching and desolate planet world called Tatooine. His job was to fix robots on the family farm and and he spent his free time flying planes through the rocky canyons. He loved his aunt and uncle but dreamed of a more exciting and adventurous life https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8wJa1L1ZCqU Search for ‘Luke Skywalker binary sunset’ CALL TO ADVENTURE One day, Luke found a broken old R2 astromech droid. It was called R2-D2 and it was a mischievous, cheeky robot who made lots of bleeps and flashes. -

ISSUE 134, AUGUST 2013 2 Imperative: Venus Continued

Imperative: Venus — Virgil L. Sharpton, Lunar and Planetary Institute Venus and Earth began as twins. Their sizes and densities are nearly identical and they stand out as being considerably more massive than other terrestrial planetary bodies. Formed so close to Earth in the solar nebula, Venus likely has Earth-like proportions of volatiles, refractory elements, and heat-generating radionuclides. Yet the Venus that has been revealed through exploration missions to date is hellishly hot, devoid of oceans, lacking plate tectonics, and bathed in a thick, reactive atmosphere. A less Earth-like environment is hard to imagine. Venus, Earth, and Mars to scale. Which L of our planetary neighbors is most similar to Earth? Hint: It isn’t Mars. PWhy and when did Earth’s and Venus’ evolutionary paths diverge? This fundamental and unresolved question drives the need for vigorous new exploration of Venus. The answer is central to understanding Venus in the context of terrestrial planets and their evolutionary processes. In addition, however, and unlike virtually any other planetary body, Venus could hold important clues to understanding our own planet — how it has maintained a habitable environment for so long and how long it can continue to do so. Precisely because it began so like Earth, yet evolved to be so different, Venus is the planet most likely to cast new light on the conditions that determine whether or not a planet evolves habitable environments. NASA’s Kepler mission and other concurrent efforts to explore beyond our star system are likely to find Earth-sized planets around Sun-sized stars within a few years. -

No Snowball Bifurcation on Tidally Locked Planets

Abbot Dorian - poster University of Chicago No Snowball Bifurcation on Tidally Locked Planets I'm planning to present on the effect of ocean dynamics on the snowball bifurcation for tidally locked planets. We previously found that tidally locked planets are much less likely to have a snowball bifurcation than rapidly rotating planets because of the insolation distribution. Tidally locked planets can still have a small snowball bifurcation if the heat transport is strong enough, but without ocean dynamics we did not find one in PlaSIM, an intermediate-complexity global climate model. We are now doing simulations in PlaSIM including a diffusive ocean heat transport and in the coupled ocean-atmosphere global climate model ROCKE3D to test whether ocean dynamics can introduce a snowball bifurcation for tidally locked planets. Abraham Carsten - poster University of Victoria Stable climate states and their radiative signals of Earth- like Aquaplanets Over Earth’s history Earth’s climate has gone through substantial changes such as from total or partial glaciation to a warm climate and vice versa. Even though causes for transitions between these states are not always clear one-dimensional models can determine if such states are stable. On the Earth, undoubtedly, three different stable climate states can be found: total or intermediate glaciation and ice-free conditions. With the help of a one-dimensional model we further analyse the effect of cloud feedbacks on these stable states and determine whether those stabalise the climate at different, intermediate states. We then generalise the analysis to the parameter space of a wide range of Earth-like aquaplanet conditions (changing, for instance, orbital parameters or atmospheric compositions) in order to examine their possible stable climate states and compare those to Earth’s climate states. -

15 Exoplanets: Habitability and Characterization

15 Exoplanets: Habitability and Characterization Until recently, the study of planetary atmospheres was 15.1 The Circumstellar Habitable Zone largely confined to the planets within our Solar System We focus our attention on Earth-like planets and on the plus the one moon (Titan) that has a dense atmosphere. possibility of remotely detecting life. We begin by defin- But, since 1991, thousands of planets have been identi- ing what life is and how we might look for it. As we shall fied orbiting stars other than our own. Lists of exopla- see, life may need to be defined differently for an astron- nets are currently maintained on the Extrasolar Planets omer using a telescope than for a biologist looking Encyclopedia (http://exoplanet.eu/), NASA’s Exoplanet through a microscope or using other in situ techniques. Archive (http://exoplanetarchive.ipac.caltech.edu/) and the Exoplanets Data Explorer (http://www.exoplanets .org/). At the time of writing (2016), over 3500 exopla- nets have been detected using a variety of methods that 15.1.1 Requirements for Life: the Importance of we discuss in Sec. 15.2. Furthermore, NASA’s Kepler Liquid Water telescope mission has reported a few thousand add- Biologists have offered various definitions of life, none of itional planetary “candidates” (unconfirmed exopla- them entirely satisfying (Benner, 2010; Tirard et al., nets), most of which are probably real. Of these 2010). One is that given by Gerald Joyce, following a detected exoplanets, a handful that are smaller than suggestion by Carl Sagan: “Life is a self-sustained chem- 1.5 Earth radii, and probably rocky, are at the right ical system capable of undergoing Darwinian evolution” distance from their stars to have conditions suitable (Joyce, 1994). -

ASTROBIOLOGY ASTROBIOLOGY: an Introduction

Physics SERIES IN ASTRONOMY AND ASTROPHYSICS LONGSTAFF SERIES IN ASTRONOMY AND ASTROPHYSICS SERIES EDITORS: M BIRKINSHAW, J SILK, AND G FULLER ASTROBIOLOGY ASTROBIOLOGY ASTROBIOLOGY: An Introduction Astrobiology is a multidisciplinary pursuit that in various guises encompasses astronomy, chemistry, planetary and Earth sciences, and biology. It relies on mathematical, statistical, and computer modeling for theory, and space science, engineering, and computing to implement observational and experimental work. Consequently, when studying astrobiology, a broad scientific canvas is needed. For example, it is now clear that the Earth operates as a system; it is no longer appropriate to think in terms of geology, oceans, atmosphere, and life as being separate. Reflecting this multiscience approach, Astrobiology: An Introduction • Covers topics such as stellar evolution, cosmic chemistry, planet formation, habitable zones, terrestrial biochemistry, and exoplanetary systems An Introduction • Discusses the origin, evolution, distribution, and future of life in the universe in an accessible manner, sparing calculus, curly arrow chemistry, and modeling details • Contains problems and worked examples and includes a solutions manual with qualifying course adoption Astrobiology: An Introduction provides a full introduction to astrobiology suitable for university students at all levels. ASTROBIOLOGY An Introduction ALAN LONGSTAFF K13515 ISBN: 978-1-4398-7576-6 90000 9 781439 875766 K13515_COVER_final.indd 1 10/10/14 2:15 PM ASTROBIOLOGY An Introduction -

1437033987698.Pdf

P a g e | 1 P a g e | 2 D C Designer Paul Elliott Publisher in PDF format Zozer Games 2015 Cover Art Ian Stead Cover Design Stephanie McAlea Interior Art Ian Stead S. Joshi Visit Zozer Games at www.zozer.weebly.com Find me on Facebook as Zozer Games All rights reserved. Reproduction of this work by any means is expressly forbidden. “Traveller” and the Traveller logo are Trademarks owned by Far Future Enterprises, Inc. and are used according to the terms of the Traveller Logo Licence version 1.0c. A copy of this licence can be obtained from Mongoose Publishing. The mention or reference to any company or product in these pages is not a challenge to the trademark or copyright concerned. “Traveller” and the Traveller logo are Trademarks owned by Far Future Enterprises, Inc. and are used with permission. The Traveller Main Rulebook is available from Mongoose Publishing. P a g e | 3 CONTENTS Introduction Star Systems Planetary Bodies Other Stars Mainworld Gas Giants Asteroids Planets The Universal World Profile Size Atmosphere Hydrographics Population Government Law Level Technology Level Bases Trade Classifications Travel Zones Starport The Procedure Part 1 – The Physical Stats Part 2 – The Social Stats Part 3 – Linking Physical & Social Stats Part 4 – The Hook P a g e | 4 INTRODUCTION The World Creator's Handbook provides advice and assistance for any Traveller referee wanting to flesh out the bones of a Universal World Profile (UWP), to turn a random string of numbers into a memorable and exciting scenario setting. Traveller is amazing, it is a tool kit that puts the creation of an entire universe into the hands of the players, allowing them to create heroes and villains, vehicles, starships, sectors of space, alien lifeforms and of course, the planets themselves. -

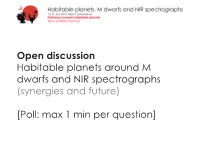

Open Discussion Habitable Planets Around M Dwarfs and NIR Spectrographs (Synergies and Future)

Open discussion Habitable planets around M dwarfs and NIR spectrographs (synergies and future) [Poll: max 1 min per question] Q1: do M dwarfs have planets? a) Yes, from microlensing (e.g. OGLE) b) Yes, from radial velocity (e.g. HARPS) c) Yes, from transits (e.g. Kepler) d) Yes, from protoplanetary disc observations e) All of the above f) No Q2: spectral type of inactive dwarfs for which NIR “>” VIS? a) M3V or earlier b) M4V c) M5V or later Q3: impact of tidal locking on habitability? a) 0% (i.e. 100% of planet surface is habitable) b) 100% (i.e. 0% of planet surface is habitable) c) 1-99% (i.e. only certain areas are habitable) Q4: spectral type of active dwarfs for which NIR “>” VIS? a) K7V or earlier b) M0V c) M1V or later Q5: impact of stellar activity on habitability? a) 0% (i.e. 100% of planet surface is habitable) b) 100% (i.e. 0% of planet surface is habitable) c) 1-99% (i.e. only certain areas are habitable) Q6: best passband for RV monitoring ~M4V? a) V, R, I b) Z c) Y d) J e) H f) K g) >3.5 μm Q7: most important parameter for HZ in M dwarfs? (but tidal locking and stellar activity) a) Ocean/initial water content b) Atmospheric composition c) Atmospheric pressure/scale height d) Stellar spectral type e) Planet magnetosphere f) Planet Bond albedo g) Other (e.g. Multiplanet system, continent distribution, migration, asteroid belt, tectonics, carbonate-silicate cycle…) Q8: best NIR spectral resolution? a) R=60,000 or less b) R=70,000-90,000 c) R=100,000 or more Q9: most probable habitable planet example? a) Tatooine (Mars, Arrakis): -

Modelling Inhomogeneous Exoplanets

Cover Page The handle http://hdl.handle.net/1887/20830 holds various files of this Leiden University dissertation. Author: Karalidi, Theodora Title: Broadband polarimetry of exoplanets : modelling signals of surfaces, hazes and clouds Issue Date: 2013-04-23 1 Introduction 1.1 A short history of exoplanets In this thesis our goal is to model the broadband polarimetric signal of exoplan- ets containing various forms of inhomogeneities, like for example continents and oceans, hazes, clouds etc. Some of these inhomogeneities, like water clouds in a planetary atmosphere are very important for the existence of life as we know it, and as we will see in this thesis tend to leave a characteristic signal on the planetary signal. Man kind has been pondering for centuries over the possible existence of exo- planets, i.e. planets that orbit around a star other than our Sun, that could harbor life. Already in ancient Greece, philosophers like Democritus and Epicurus were speaking of the existence of infinite worlds, either like or unlike ours. “In some worlds there is no Sun and Moon, in others they are larger than in our world, and in others more numerous. In some parts there are more worlds, in others fewer (...); in some parts they are arising, in others failing. There are some worlds devoid of living creatures or plants or any moisture.” - Democritus (460–370 B.C.) Aristotle’s authority and opinion that there “cannot be more worlds than one”, shadowed any further advancement on the topic for centuries. Giordano Bruno and a couple of centuries later Christiaan Huygens among others will come back to this topic, and claim the existence of multiple worlds like ours. -

The Atmospheres of Extrasolar Planets and Brown Dwarfs

Publications of the Astronomical Society of Australia (PASA) c Astronomical Society of Australia 2018; published by Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/pasa.2018.xxx. The Dawes Review 3: The Atmospheres of Extrasolar Planets and Brown Dwarfs Jeremy Bailey1 1School of Physics, University of New South Wales, NSW, 2052, Australia Abstract The last few years has seen a dramatic increase in the number of exoplanets known and in the range of methods for characterising their atmospheric properties. At the same time, new discoveries of increasingly cooler brown dwarfs have pushed down their temperature range which now extends down to Y-dwarfs of <300 K. Modelling of these atmospheres has required the development of new techniques to deal with the molecular chemistry and clouds in these objects. The atmospheres of brown dwarfs are relatively well understood, but some problems remain, in particular the behavior of clouds at the L/T transition. Observational data for exoplanet atmosphere characterization is largely limited to giant exoplanets that are hot because they are near to their star (hot Jupiters) or because they are young and still cooling. For these planets there is good evidence for the presence of CO and H2O absorptions in the IR. Sodium absorption is observed in a number of objects. Reflected light measurements show that some giant exoplanets are very dark, indicating a cloud free atmosphere. However, there is also good evidence for clouds and haze in some other planets. It is also well established that some highly irradiated planets have inflated radii, though the mechanism for this inflation is not yet clear. -

Thesearchforetlifeintheunivers

Chapter-1 (The Grand Cosmos) - Why Extra-terrestrials.............................................................. 1 - In the Beginning....................................................................... 5 - The other Fantastic Four.......................................................... 8 - Let there be Light................................................................... 14 - To Be or not to Be.................................................................. 16 - Future from the Beyond......................................................... 23 Chapter-2 (Religions, Ancient Astronauts, Histories, UFOs & E.Ts) - The Sacred Whispers............................................................. 26 - The Ancient Astronauts Theory............................................. 30 - UFO s in Medieval Paintings.................................................. 34 - Ancient Astronauts or Ancient Archeology?........................ 35 - UFOs themselves................................................................... 38 - The Search for Extra-Terrestrial Life: The Beginning.............44 Chapter-3 (Echoes from our Solar District) -The Story So Far..................................................................... 50 -The Water Worlds................................................................... 50 -Solar System: A very brief Tour.............................................. 52 - The Red Planet...................................................................... 53 - The Evening Star.................................................................. -

Mars Is the Fourth Planet from the Sun and Is a Dusty, Cold, Desert Planet with a Thin Atmosphere

Image Courtesy of NASA Mars is the fourth planet from the Sun and is a dusty, cold, desert planet with a thin atmosphere. It is one of the most explored celestial bodies and has polar ice caps, Mars weather, and seasons like Earth. It is the only planet that NASA has sent rovers to, which are Terrestrial Planet currently exploring the planet’s surface. The Curiosity Rover has sent back numerous photographs and data it has collected while Year = 687 Earth Days roaming the planet for the last eight years. One of the missions of the Mars rovers is to Day = 24.6 Earth Hours search for evidence of life. The field of 1.9 times smaller than earth Astrobiology, exploring the potential for life Radius = 2,106 miles beyond Earth, has been intertwined with the study of Mars since 1976 when NASA first 142 million miles from Sun looked to the planet for life. Gravity = 12.2 ft/s^2 Alien life has long been associated with Mars and has also fascinated humans throughout our history. While there has been no evidence of life found on Mars or any of the other planets in our solar system, that has not stopped humans from fantasizing about what that life may look and act like. In popular culture we frequently see little humanoid creatures, often Image Courtesy of NASA green or grey, that travel in disc Johannes Kepler, a shaped flying saucers. What do you sixteenth and think extraterrestrial life looks like? seventeenth century German astronomer, developed theories he called the laws of planetary motion by observing the Public Domain movements of Mars.