Contents Overview

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Evolution of Star Habitable Zones

The Evolution of Star Habitable Zones Jeffrey J. Wolynski November 17, 2018 Rockledge, FL 32922 Abstract: It was discovered that planets are older, evolving stars. This means the Circumstellar Habitable Zone collapses and/or shrinks into the star itself, thus evolves as the star evolves. Explanation is provided. The habitable zone of a star is the area where liquid water exists or can exist. Since stars cool down and become water worlds as they evolve, combining their hydrogen with the leftover oxygen in large amounts, it is easy to see what happens. The star is too hot in the beginning to form water, or sustain it, but it can heat up other much colder stars allowing them to pool water on their surfaces from a distance. As the star cools and evolves, the distance it can do this diminishes considerably and its habitable zone shrinks. Blue giants have the largest habitable zones, but they quickly contract because they are so young and are evolving rapidly to cooler, less massive states. What this means is that the time variable for the habitable zones of these objects is quite small. The activity of more evolved stars around blue giants should be short-lived, but interesting to say the least. White stars have smaller habitable zones but are still very large. Orange dwarfs have even smaller habitable zones, as well show a noticeable thinning of the zone as opposed to earlier stages. Red dwarfs have very small external habitable zones and the smallest external habitable zone belongs to only the smallest brown dwarfs, which still have a small amount of heat to radiate the surface of another more evolved star. -

Introduction to Astronomy from Darkness to Blazing Glory

Introduction to Astronomy From Darkness to Blazing Glory Published by JAS Educational Publications Copyright Pending 2010 JAS Educational Publications All rights reserved. Including the right of reproduction in whole or in part in any form. Second Edition Author: Jeffrey Wright Scott Photographs and Diagrams: Credit NASA, Jet Propulsion Laboratory, USGS, NOAA, Aames Research Center JAS Educational Publications 2601 Oakdale Road, H2 P.O. Box 197 Modesto California 95355 1-888-586-6252 Website: http://.Introastro.com Printing by Minuteman Press, Berkley, California ISBN 978-0-9827200-0-4 1 Introduction to Astronomy From Darkness to Blazing Glory The moon Titan is in the forefront with the moon Tethys behind it. These are two of many of Saturn’s moons Credit: Cassini Imaging Team, ISS, JPL, ESA, NASA 2 Introduction to Astronomy Contents in Brief Chapter 1: Astronomy Basics: Pages 1 – 6 Workbook Pages 1 - 2 Chapter 2: Time: Pages 7 - 10 Workbook Pages 3 - 4 Chapter 3: Solar System Overview: Pages 11 - 14 Workbook Pages 5 - 8 Chapter 4: Our Sun: Pages 15 - 20 Workbook Pages 9 - 16 Chapter 5: The Terrestrial Planets: Page 21 - 39 Workbook Pages 17 - 36 Mercury: Pages 22 - 23 Venus: Pages 24 - 25 Earth: Pages 25 - 34 Mars: Pages 34 - 39 Chapter 6: Outer, Dwarf and Exoplanets Pages: 41-54 Workbook Pages 37 - 48 Jupiter: Pages 41 - 42 Saturn: Pages 42 - 44 Uranus: Pages 44 - 45 Neptune: Pages 45 - 46 Dwarf Planets, Plutoids and Exoplanets: Pages 47 -54 3 Chapter 7: The Moons: Pages: 55 - 66 Workbook Pages 49 - 56 Chapter 8: Rocks and Ice: -

The Evolving Universe and the Origin of Life

Pekka Teerikorpi · Mauri Valtonen · Kirsi Lehto · Harry Lehto · Gene Byrd · Arthur Chernin The Evolving Universe and the Origin of Life The Search for Our Cosmic Roots Second Edition The Evolving Universe and the Origin of Life Pekka Teerikorpi • Mauri Valtonen • Kirsi Lehto • Harry Lehto • Gene Byrd • Arthur Chernin The Evolving Universe and the Origin of Life The Search for Our Cosmic Roots Second Edition 123 Pekka Teerikorpi Mauri Valtonen Department of Physics and Astronomy Department of Physics and Astronomy University of Turku University of Turku Turku, Finland Turku, Finland Kirsi Lehto Harry Lehto Department of Biology Department of Physics and Astronomy University of Turku University of Turku Turku, Finland Turku, Finland Gene Byrd Arthur Chernin Department of Physics and Astronomy Sternberg Astronomical Institute The University of Alabama Moscow University Tuscaloosa, AL, USA Moscow, Russia ISBN 978-3-030-17920-5 ISBN 978-3-030-17921-2 (eBook) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-17921-2 1st edition: © 2009 Springer Science+Business Media, LLC 2nd edition: © Springer Nature Switzerland AG 2019 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specific statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. -

![Arxiv:2005.14671V2 [Astro-Ph.EP] 30 Jun 2020 Tion Et Al](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8147/arxiv-2005-14671v2-astro-ph-ep-30-jun-2020-tion-et-al-408147.webp)

Arxiv:2005.14671V2 [Astro-Ph.EP] 30 Jun 2020 Tion Et Al

Draft version July 1, 2020 Typeset using LATEX twocolumn style in AASTeX62 The Gaia-Kepler Stellar Properties Catalog. II. Planet Radius Demographics as a Function of Stellar Mass and Age Travis A. Berger,1 Daniel Huber,1 Eric Gaidos,2 Jennifer L. van Saders,1 and Lauren M. Weiss1 1Institute for Astronomy, University of Hawai`i, 2680 Woodlawn Drive, Honolulu, HI 96822, USA 2Department of Earth Sciences, University of Hawai`i at M¯anoa, Honolulu, HI 96822, USA ABSTRACT Studies of exoplanet demographics require large samples and precise constraints on exoplanet host stars. Using the homogeneous Kepler stellar properties derived using Gaia Data Release 2 by Berger et al.(2020), we re-compute Kepler planet radii and incident fluxes and investigate their distributions with stellar mass and age. We measure the stellar mass dependence of the planet radius valley to +0:21 be d log Rp/d log M? = 0:26−0:16, consistent with the slope predicted by a planet mass dependence on stellar mass (0.24{0.35) and core-powered mass-loss (0.33). We also find first evidence of a stellar age dependence of the planet populations straddling the radius valley. Specifically, we determine that the fraction of super-Earths (1{1.8 R⊕) to sub-Neptunes (1.8{3.5 R⊕) increases from 0.61 ± 0.09 at young ages (< 1 Gyr) to 1.00 ± 0.10 at old ages (> 1 Gyr), consistent with the prediction by core-powered mass- loss that the mechanism shaping the radius valley operates over Gyr timescales. Additionally, we find a tentative decrease in the radii of relatively cool (Fp < 150 F⊕) sub-Neptunes over Gyr timescales, which suggests that these planets may possess H/He envelopes instead of higher mean molecular weight atmospheres. -

Westminsterresearch the Astrobiology Primer V2.0 Domagal-Goldman, S.D., Wright, K.E., Adamala, K., De La Rubia Leigh, A., Bond

WestminsterResearch http://www.westminster.ac.uk/westminsterresearch The Astrobiology Primer v2.0 Domagal-Goldman, S.D., Wright, K.E., Adamala, K., de la Rubia Leigh, A., Bond, J., Dartnell, L., Goldman, A.D., Lynch, K., Naud, M.-E., Paulino-Lima, I.G., Kelsi, S., Walter-Antonio, M., Abrevaya, X.C., Anderson, R., Arney, G., Atri, D., Azúa-Bustos, A., Bowman, J.S., Brazelton, W.J., Brennecka, G.A., Carns, R., Chopra, A., Colangelo-Lillis, J., Crockett, C.J., DeMarines, J., Frank, E.A., Frantz, C., de la Fuente, E., Galante, D., Glass, J., Gleeson, D., Glein, C.R., Goldblatt, C., Horak, R., Horodyskyj, L., Kaçar, B., Kereszturi, A., Knowles, E., Mayeur, P., McGlynn, S., Miguel, Y., Montgomery, M., Neish, C., Noack, L., Rugheimer, S., Stüeken, E.E., Tamez-Hidalgo, P., Walker, S.I. and Wong, T. This is a copy of the final version of an article published in Astrobiology. August 2016, 16(8): 561-653. doi:10.1089/ast.2015.1460. It is available from the publisher at: https://doi.org/10.1089/ast.2015.1460 © Shawn D. Domagal-Goldman and Katherine E. Wright, et al., 2016; Published by Mary Ann Liebert, Inc. This Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by- nc/4.0/) which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited. The WestminsterResearch online digital archive at the University of Westminster aims to make the research output of the University available to a wider audience. -

Monday, November 13, 2017 WHAT DOES IT MEAN to BE HABITABLE? 8:15 A.M. MHRGC Salons ABCD 8:15 A.M. Jang-Condell H. * Welcome C

Monday, November 13, 2017 WHAT DOES IT MEAN TO BE HABITABLE? 8:15 a.m. MHRGC Salons ABCD 8:15 a.m. Jang-Condell H. * Welcome Chair: Stephen Kane 8:30 a.m. Forget F. * Turbet M. Selsis F. Leconte J. Definition and Characterization of the Habitable Zone [#4057] We review the concept of habitable zone (HZ), why it is useful, and how to characterize it. The HZ could be nicknamed the “Hunting Zone” because its primary objective is now to help astronomers plan observations. This has interesting consequences. 9:00 a.m. Rushby A. J. Johnson M. Mills B. J. W. Watson A. J. Claire M. W. Long Term Planetary Habitability and the Carbonate-Silicate Cycle [#4026] We develop a coupled carbonate-silicate and stellar evolution model to investigate the effect of planet size on the operation of the long-term carbon cycle, and determine that larger planets are generally warmer for a given incident flux. 9:20 a.m. Dong C. F. * Huang Z. G. Jin M. Lingam M. Ma Y. J. Toth G. van der Holst B. Airapetian V. Cohen O. Gombosi T. Are “Habitable” Exoplanets Really Habitable? A Perspective from Atmospheric Loss [#4021] We will discuss the impact of exoplanetary space weather on the climate and habitability, which offers fresh insights concerning the habitability of exoplanets, especially those orbiting M-dwarfs, such as Proxima b and the TRAPPIST-1 system. 9:40 a.m. Fisher T. M. * Walker S. I. Desch S. J. Hartnett H. E. Glaser S. Limitations of Primary Productivity on “Aqua Planets:” Implications for Detectability [#4109] While ocean-covered planets have been considered a strong candidate for the search for life, the lack of surface weathering may lead to phosphorus scarcity and low primary productivity, making aqua planet biospheres difficult to detect. -

Steven D. Vance –

Steven D. Vance Research Focus My research focuses on using geophysical and geochemical methods to understand ocean worlds: how oceans couple to the thermal evolution and composition, and what this might mean for life. I am also interested in the global geochemical fluxes in ocean worlds, by analogy to biogeochemical fluxes in the Earth system. My experimental research involves collecting thermodynamic equations of state for fluids and ices. I have applied these equations of state to evaluating oceanic heat transport and double diffusive convection in Europa, and to the geophysical constraints imposed by ocean composition on the radial structures of Europa, Ganymede, Callisto, Enceladus, and Titan. In recent years I have used these models to explore the parameter space of possible geophysical signals—seismic, magnetic, and gravitational—in the interest of improving the fidelity of returned science from investigations of ocean composition and habitability. Education 2001–2007 Ph.D., University of Washington, Seattle, Geophysics and Astrobiology. 1996–2000 B.S., University of California, Santa Cruz, Physics (with honors). Ph.D. Thesis title Thesis title: High Pressure and Low Temperature Equations of State for Aqueous Sulfate Solutions: Applications to the Search for Life in Extraterrestrial Oceans, with Particular Reference to Europa advisor Prof. J. Michael Brown Bachelor Thesis title The Role of Methanol Frost in Particle Sticking and the Formation of Planets in the Early Solar Nebula advisor Prof. Frank G. Bridges Current Appointments Research -

Abscicon 2019 Summary

Summary of AbSciCon (Astrobiology Science Conference) 2019 • AbSciCon 2019 Theme: Understanding and Enabling the Search for Life on Worlds Near and Far • Event Details: • Event Location: Bellevue, WA • Approximate # of attendees: 900 (>3x larger than 2 years ago) • Attendee Demographics: Academia / Researchers / NASA Kate Craft, JHU APL, [email protected] 1 AbSciCon 2019 Topics • Star-planet-planetary system interactions and habitability • Alternative and agnostic biosignatures • Understanding the environments of early Earth • Evidence for early life on Earth • Subsurface habitability and life • Ocean worlds near and far • Characterizing habitable zone exoplanets • Transition of prebiotic chemistry to biology • Energy sources in the environment and metabolic pathways that use that energy • Terrestrial planets orbiting M dwarfs 2 Nature May Present Challenges to Higher- order Life Forms • Earth has special conditions that may skew our view of how common higher-order life is – We have learned that Ocean Worlds are more common than had been thought – Ocean Worlds with frozen crusts are blocked from solar energy, depend on chemical energy from rocks, may limit the biosphere – Ocean Worlds with a deep ocean will have a bottom layer of “ice-VI” that might block water from rock, starving nutrients / chemical energy. – Most Ocean Worlds likely occur around M-dwarf stars like Proxima Centauri. They flare early and push planets in the “habitable zone” through an early Venus phase. Sun-like G-type stars are much more stable. Artist’s conception of Earth- sized planet discovered – Planets orbiting their stars can have large variations in obliquity orbiting Proxima Centauri causing extreme climate change on liquid surfaces. -

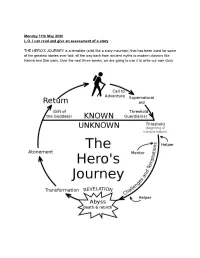

Monday 11Th May 2020 L.O. I Can Read and Give an Assessment of a Story

Monday 11th May 2020 L.O. I can read and give an assessment of a story THE HERO’S JOURNEY is a template (a bit like a story mountain) that has been used for some of the greatest stories ever told, all the way back from ancient myths to modern classics like Narnia and Star wars. Over the next three weeks, we are going to use it to write our own story One of the reasons STAR WARS is such a great movie is it because it follows the HERO’S JOURNEY model. Today, you are going to read / watch this version of the Hero’s journey and see how it fits into the format for our first act! The subtitles just refer to the stages of the story - don’t worry about them yet! Just read the story and if you have internet access look up / click on the clips on youtube. ORDINARY WORLD Luke Skywalker was a poor and humble boy who lived with his aunt and uncle in a scorching and desolate planet world called Tatooine. His job was to fix robots on the family farm and and he spent his free time flying planes through the rocky canyons. He loved his aunt and uncle but dreamed of a more exciting and adventurous life https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8wJa1L1ZCqU Search for ‘Luke Skywalker binary sunset’ CALL TO ADVENTURE One day, Luke found a broken old R2 astromech droid. It was called R2-D2 and it was a mischievous, cheeky robot who made lots of bleeps and flashes. -

ISSUE 134, AUGUST 2013 2 Imperative: Venus Continued

Imperative: Venus — Virgil L. Sharpton, Lunar and Planetary Institute Venus and Earth began as twins. Their sizes and densities are nearly identical and they stand out as being considerably more massive than other terrestrial planetary bodies. Formed so close to Earth in the solar nebula, Venus likely has Earth-like proportions of volatiles, refractory elements, and heat-generating radionuclides. Yet the Venus that has been revealed through exploration missions to date is hellishly hot, devoid of oceans, lacking plate tectonics, and bathed in a thick, reactive atmosphere. A less Earth-like environment is hard to imagine. Venus, Earth, and Mars to scale. Which L of our planetary neighbors is most similar to Earth? Hint: It isn’t Mars. PWhy and when did Earth’s and Venus’ evolutionary paths diverge? This fundamental and unresolved question drives the need for vigorous new exploration of Venus. The answer is central to understanding Venus in the context of terrestrial planets and their evolutionary processes. In addition, however, and unlike virtually any other planetary body, Venus could hold important clues to understanding our own planet — how it has maintained a habitable environment for so long and how long it can continue to do so. Precisely because it began so like Earth, yet evolved to be so different, Venus is the planet most likely to cast new light on the conditions that determine whether or not a planet evolves habitable environments. NASA’s Kepler mission and other concurrent efforts to explore beyond our star system are likely to find Earth-sized planets around Sun-sized stars within a few years. -

Ocean Worlds : May 21–23, 2018, Houston, Texas

Program Ocean Worlds May 21–23, 2018 • Houston, Texas Organizers Lunar and Planetary Institute Universities Space Research Association Convener Louise Prockter Lunar and Planetary Institute Science Organizing Committee Julie Castillo NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory Christopher German Wood Hole Oceanographic Institution Jonathan Kay Lunar and Planetary Institute Marc Neveu NASA Headquarters Beth Orcutt Bigelow Laboratory for Ocean Sciences Paul Schenk Lunar and Planetary Institute Christophe Sotin NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory Hajime Yano Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency Lunar and Planetary Institute 3600 Bay Area Boulevard Houston TX 77058-1113 Abstracts for this meeting are available via the meeting website at www.hou.usra.edu/meetings/oceanworlds2018/ Abstracts can be cited as Author A. B. and Author C. D. (2018) Title of abstract. In Ocean Worlds, Abstract #XXXX. LPI Contribution No. 2085, Lunar and Planetary Institute, Houston. Guide to Sessions Monday, May 21, 2018 1:00 p.m. Lecture Hall Opening Session: Setting the Framework 5:30 p.m. Great Room Poster Session Tuesday, May 22, 2018 8:30 a.m. Lecture Hall Session I 12:45p.m. Great Room Poster Viewing Tuesday, May 22, 2018 1:30 p.m. Lecture Hall Session II Wednesday, May 23, 2018 8:30 a.m. Lecture Hall Session III 1:00 p.m. Lecture Hall Session IV Program Monday, May 21, 2018 OPENING SESSION: SETTING THE FRAMEWORK 1:00 p.m. Lecture Hall Chair: Christopher German 1:00 p.m. German C. R. * Prockter L. * Opening Remarks 1:15 p.m. Hand K. P. * Ocean Worlds of the Outer Solar System [#6042] I will provide an overview of why we think we know ocean worlds exist, what we know about the physical and chemical conditions that likely persist on these worlds, and how we may proceed in our search for biosignatures on these worlds. -

Curriculum Vitae for Cecilia M. Bitz 22 May 2019 Department of Atmospheric Sciences Box 351640 University of Washington Seattle, WA 98195-1640

Curriculum Vitae for Cecilia M. Bitz 22 May 2019 Department of Atmospheric Sciences Box 351640 University of Washington Seattle, WA 98195-1640 Education 1997 PhD Atmospheric Sciences University of Washington Dissertation title: A Model Study of Natural Variability in the Arctic Climate 1990 MS Physics University of Washington 1988 BS Engineering Physics Oregon State University Professional positions held 2019 (July) –Present Chair of Department of Atmospheric Sciences, University of Washington 2017–Present Directory Program on Climate Change, University of Washington 2013–Present Professor, Atmospheric Sciences, University of Washington 2012–Present Faculty, Astrobiology Program, University of Washington 2006–Present Adjunct Physicist, Polar Science Center, University of Washington 2009–2013 Associate Professor, Atmospheric Sciences, University of Washington 2005–2009 Assistant Professor, Atmospheric Sciences, University of Washington 2001–2005 Physicist, Polar Science Center, Applied Physics Lab, University of Washington 2000 - 2001 NOAA Climate and Global Change Visiting Scholar, Polar Science Center, Applied Physics Laboratory, University of Washington 1999 Apr.-Dec. Research Associate, Quaternary Research Center, University of Washington 1997 -1999 Research Associate, School of Earth & Ocean Sciences, Univ. of Victoria, Canada. 1993-1997 Research Assistant, Department of Atmospheric Sciences, University of Washington 1988-1993 Research Assistant, Department of Physics, University of Washington Awards and Honors Graduate Student Invited