The Grieving Kangaroo Photograph Revisited

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Constitutional Status of Morals Legislation

Kentucky Law Journal Volume 98 | Issue 1 Article 2 2009 The onsC titutional Status of Morals Legislation John Lawrence Hill Indiana University-Indianapolis Follow this and additional works at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/klj Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, and the Law and Society Commons Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits you. Recommended Citation Hill, John Lawrence (2009) "The onC stitutional Status of Morals Legislation," Kentucky Law Journal: Vol. 98 : Iss. 1 , Article 2. Available at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/klj/vol98/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Kentucky Law Journal by an authorized editor of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TKenf]iky Law Jornal VOLUME 98 2009-2010 NUMBER I ARTICLES The Constitutional Status of Morals Legislation John Lawrence Hiff TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION I. MORALS LEGISLATION AND THE HARM PRINCIPLE A. Some Difficulties with the Concept of "MoralsLegislation" B. The Near Irrelevance of the PhilosophicDebate C. The Concept of "Harm" II. DEFINING THE SCOPE OF THE PRIVACY RIGHT IN THE CONTEXT OF MORALS LEGISLATION III. MORALS LEGISLATION AND THE PROBLEMS OF RATIONAL BASIS REVIEW A. The 'RationalRelation' Test in Context B. The Concept of a Legitimate State Interest IV. MORALITY AS A LEGITIMATE STATE INTEREST: FIVE TYPES OF MORAL PURPOSE A. The Secondary or IndirectPublic Effects of PrivateActivity B. Offensive Conduct C. Preventingthe Corruptionof Moral Character D. ProtectingEssential Values andSocial Institutions E. -

Rhode Island Historical Cemetery Commission Handbook

Rhode Island Historical Cemetery Commission Handbook December 2014 Table of Contents 1. Opening Statement. .................................................................................................................................. 1 2. Working in a historical cemetery. ............................................................................................................ 2 3. Rhode Island General Laws pertaining to Cemeteries. CHAPTER 11-20 Graves and Corpses § 11-20-1 Disinterment of body. .................................................................................................... 3 § 11-20-1.1 Mutilation of dead human bodies – Penalties – Exemptions. ..................................... 3 § 11-20-1.2 Necrophilia. .................................................................................................................. 3 § 11-20-2 Desecration of grave. ...................................................................................................... 4 § 11-20-3 Removal of marker on veteran's grave........................................................................... 4 CHAPTER 19-3.1 Trust Powers § 19-3.1-5 Financial institutions administering burial grounds. ..................................................... 5 CHAPTER 23-18 Cemeteries § 23-18-1 Definitions. ..................................................................................................................... 6 § 23-18-2 Location of mausoleums and columbaria. ..................................................................... 6 -

Of Iowa Code

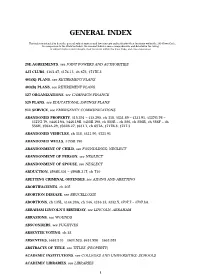

GENERAL INDEX This index is intended to describe general subject matters and law concepts and to identify their locations within the 2014 Iowa Code. In comparison to the Skeleton Index, the General Index is more comprehensive and detailed in the listing of subject matters and concepts, their locations within the Iowa Code, and cross-references. 28E AGREEMENTS, see JOINT POWERS AND AUTHORITIES 4-H CLUBS, §163.47, §174.13, ch 673, §717E.3 401(K) PLANS, see RETIREMENT PLANS 403(B) PLANS, see RETIREMENT PLANS 527 ORGANIZATIONS, see CAMPAIGN FINANCE 529 PLANS, see EDUCATIONAL SAVINGS PLANS 911 SERVICE, see EMERGENCY COMMUNICATIONS ABANDONED PROPERTY, §15.291 – §15.295, ch 318, §321.89 – §321.91, §327G.76 – §327G.79, §446.19A, §446.19B, §455B.190, ch 555B – ch 556, ch 556B, ch 556F – ch 556H, §562A.29, §562B.27, §631.1, ch 657A, §717B.8, §727.3 ABANDONED VEHICLES, ch 318, §321.90, §321.91 ABANDONED WELLS, §455B.190 ABANDONMENT OF CHILD, see FOUNDLINGS; NEGLECT ABANDONMENT OF PERSON, see NEGLECT ABANDONMENT OF SPOUSE, see NEGLECT ABDUCTION, §598B.301 – §598B.317, ch 710 ABETTING CRIMINAL OFFENSES, see AIDING AND ABETTING ABORTIFACIENTS, ch 205 ABORTION DISEASE, see BRUCELLOSIS ABORTIONS, ch 135L, §144.29A, ch 146, §216.13, §232.5, §707.7 – §707.8A ABRAHAM LINCOLN’S BIRTHDAY, see LINCOLN, ABRAHAM ABRASIONS, see WOUNDS ABSCONDERS, see FUGITIVES ABSENTEE VOTING, ch 53 ABSENTEES, §633.510 – §633.520, §633.580 – §633.585 ABSTRACTS OF TITLE, see TITLES (PROPERTY) ACADEMIC INSTITUTIONS, see COLLEGES AND UNIVERSITIES; SCHOOLS ACADEMIC LIBRARIES, see -

Pseudonecrophilia Following Spousal Homicide

CASE REPORT J. Reid Meloy, I Ph.D. Pseudonecrophilia Following Spousal Homicide REFERENCE: Meloy, J. R., "Pseudonecrophilla Following children, .ages 1. and 3, and her common law husband, aged 26. Spousal Homicide," Journal of Forensic Sciences, JFSCA, Vol. 41, No.4, July 1996, pp. 706--708. She was m the hthotomy position with her hips extended and her knees flexed. ABSTRACf: A c.ase of pseudonecrophilia by a 26-year-old male She was nude except for clothing pulled above her breasts. following the mulliple stabbing death of his wife is reported. Intoxi Blood stains indicated that she had been dragged from the kitchen cated wah alco~~J at the .tim~, the man positioned the corpse of approximately seven feet onto the living room carpet. The murder hIS ~~ouse t? faclh!ate vagInal Intercourse with her in the lithotomy weapon, a 14.5 inch switchblade knife, was found in a kitchen posltlon while he viewed soft core pornography on television. Clini drawer. The children were asleep in the bedroom. Autopsy revealed cal interview, a review ofhistory, and psychological testing revealed .. 61 stab wounds to her abdomen, chest. back, and upper and lower dIagnoses of antisocial per~on~lity dis<;>rder and major depression (DSM-IV, Amencan Psychlatnc AssocIation, 1994). There was no extremities, the latter consistent with defensive wounds. Holes in evidence of psychosis, but some indices of mild neuropsychological the clothing matched the wound pattern on the body. Vaginal Impainnent. T~e moti~ations for this rare case ofpseudonecrophilia smears showed semen, but oral and anal smears did not. -

NECROPHILIC and NECROPHAGIC SERIAL KILLERS Approval Page

Running head: NECROPHILIC AND NECROPHAGIC SERIAL KILLERS Approval Page: Florida Gulf Coast University Thesis APPROVAL SHEET This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science Christina Molinari Approved: August 2005 Dr. David Thomas Committee Chair / Advisor Dr. Shawn Keller Committee Member The final copy of this thesis has been examined by the signatories, and we find that both the content and the form meet acceptable presentation standards of scholarly work in the above mentioned discipline. NECROPHILIC AND NECROPHAGIC SERIAL KILLERS 1 Necrophilic and Necrophagic Serial Killers: Understanding Their Motivations through Case Study Analysis Christina Molinari Florida Gulf Coast University NECROPHILIC AND NECROPHAGIC SERIAL KILLERS 2 Table of Contents Abstract ........................................................................................................................................... 5 Literature Review............................................................................................................................ 7 Serial Killing ............................................................................................................................... 7 Characteristics of sexual serial killers ..................................................................................... 8 Paraphilia ................................................................................................................................... 12 Cultural and Historical Perspectives -

Fantasies of Necrophilia in Early Modern English Drama

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 2-2014 Exquisite Corpses: Fantasies of Necrophilia in Early Modern English Drama Linda K. Neiberg Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/1420 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] EXQUISITE CORPSES: FANTASIES OF NECROPHILIA IN EARLY MODERN ENGLISH DRAMA by LINDA K. NEIBERG A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in English in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2014 ii © 2014 LINDA K. NEIBERG All Rights Reserved iii This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in English in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Mario DiGangi Date Chair of Examining Committee Carrie Hintz Date Acting Executive Officer Mario DiGangi Richard C. McCoy Steven F. Kruger Supervisory Committee THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iv Abstract EXQUISITE CORPSES: FANTASIES OF NECROPHILIA IN EARLY MODERN ENGLISH DRAMA by LINDA K. NEIBERG Adviser: Professor Mario DiGangi My dissertation examines representations of necrophilia in Elizabethan and Jacobean drama. From the 1580s, when London’s theatres began to flourish, until their closure by Parliament in 1642, necrophilia was deployed as a dramatic device in a remarkable number of plays. -

Humanistic Climate Philosophy: Erich Fromm Revisited

Humanistic Climate Philosophy: Erich Fromm Revisited by Nicholas Dovellos A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Philosophy College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Co-Major Professor (Deceased): Martin Schönfeld, Ph.D. Co-Major Professor: Alex Levine, Ph.D. Co-Major Professor: Joshua Rayman, Ph.D. Govindan Parayil, Ph.D. Michael Morris, Ph.D. George Philippides, Ph.D. Date of Approval: July 7, 2020 Key Words: Climate Ethics, Actionability, Psychoanalysis, Econo-Philosophy, Productive Orientation, Biophilia, Necrophilia, Pathology, Narcissism, Alienation, Interiority Copyright © 2020 Nicholas Dovellos Table of Contents Abstract .................................................................................................................................... iii Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 1 Part I: The Current Climate Conversation: Work and Analysis of Contemporary Ethicists ........ 13 Chapter 1: Preliminaries ............................................................................................................ 16 Section I: Cape Town and Totalizing Systems ............................................................... 17 Section II: A Lack in Step Two: Actionability ............................................................... 25 Section III: Gardiner’s Analysis .................................................................................... -

Sexual Attraction to Corpses: a Psychiatric Review of Necrophilia

Sexual Attraction to Corpses: A Psychiatric Review of Necrophilia Jonathan P. Rosman, MD; and Phillip J. Resnick, MD The authors review 122 cases (88 from the world literature and 34 unpublished cases) manifesting necrophilic acts or fantasies. They distinguish genuine necro- philia from pseudonecrophilia and classify true necrophilia into three types: ne- crophilic homicide, "regular" necrophilia, and necrophilic fantasy. Neither psychosis, mental retardation, nor sadism appears to be inherent in necrophilia. The most common motive for necrophilia is possession of an unresisting and unrejecting partner. Necrophiles often choose occupations that put them in contact with corpses. Some necrophiles who had occupational access to corpses committed homicide nevertheless. Psychodynamic themes, defense mechanisms, and treatment for this rare disorder are discussed. "Shall I believe about King Waldemar and Charle- That unsubstantial death is amorous, mag~e.'.~Necrophilia was considered by And that the lean abhorred monster keeps Thee here in dark to be his paramour?" the Catholic Church to be neither whor- -William Shakespeare' ing ("fornicatio") nor bestiality, but "pollution with a tendency to ~horing."~ Necrophilia, a sexual attraction to corpses, In more recent times, necrophilia has is a rare disorder that has been known been associated with cannibalism and since ancient times. According to Hero- myths of vampirism. The vampire, who dotus,' the ancient Egyptians took pre- has been romanticized by the Dracula cautions against necrophilia by prohib- tales, obtains a feeling of power from his iting the corpses of the wives of men of victims, "like I had taken something rank from being delivered immediately powerful from them."' Cannibalistic to the embalmers, for fear that the em- tribal rituals are based on the notion that balmers would violate them. -

Critical Corpse Studies: Engaging with Corporeality and Mortality in Curriculum

Taboo: The Journal of Culture and Education Volume 19 Issue 3 The Affect of Waste and the Project of Article 10 Value: April 2020 Critical Corpse Studies: Engaging with Corporeality and Mortality in Curriculum Mark Helmsing George Mason University, [email protected] Cathryn van Kessel University of Alberta, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/taboo Recommended Citation Helmsing, M., & van Kessel, C. (2020). Critical Corpse Studies: Engaging with Corporeality and Mortality in Curriculum. Taboo: The Journal of Culture and Education, 19 (3). Retrieved from https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/taboo/vol19/iss3/10 This Article is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Article in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Article has been accepted for inclusion in Taboo: The Journal of Culture and Education by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 140 CriticalTaboo, Late Corpse Spring Studies 2020 Critical Corpse Studies Engaging with Corporeality and Mortality in Curriculum Mark Helmsing & Cathryn van Kessel Abstract This article focuses on the pedagogical questions we might consider when teaching with and about corpses. Whereas much recent posthumanist writing in educational research takes up the Deleuzian question “what can a body do?,” this article investigates what a dead body can do for students’ encounters with life and death across the curriculum. -

America Without the Death Penalty

................................ America without the Death Penalty .................................. America without the Death Penalty States Leading John F. Galliher the Way Larry W. Koch David Patrick Keys Teresa J. Guess Northeastern University Press Boston published by university press of new england hanover and london To Hugo Adam Bedau Northeastern University Press Published by University Press of New England One Court Street, Lebanon, NH 03766 www.upne.com ᭧ 2002 by John F. Galliher First Northeastern University Press/UPNE paperback edition 2005 Printed in the United States of America 54321 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review. Members of educational institutions and organizations wishing to photocopy any of the work for classroom use, or authors and publishers who would like to obtain permission for any of the material in the work, should contact Permissions, University Press of New England, One Court Street, Lebanon, NH 03766. ISBN for the paperback edition 1–55553–639–5 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data America without the death penalty : states leading the way / John F. Galliher . [et al.]. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 1–55553–529–1 (cloth : alk. paper) Capital punishment—United States—States. I. Galliher, John F. HV8699.U5 G35 2002 364.66Ј0973—dc21 2002004923 -

The Constitution After Death

THE CONSTITUTION AFTER DEATH Fred O. Smith, Jr.* From mandating separate and unequal gravesites, to condoning mutilation after lynchings, to engaging in cover-ups after wrongful police shootings, governmental actors have often degraded dignity in death. This Article offers an account of the constitutional law of the dead and takes aim at a legal rule that purports to categorically exclude the dead from constitutional protection. The rule rests on two faulty premises. The first is that the dead are incapable of being rights-holders. The second is that there are no sound policy reasons for recognizing constitutional rights after death. The first premise is undone by a robust common law tradition of protecting the dead’s dignitary interests and testamentary will. As for the second premise, posthumous rights can promote human pursuits by pro- tecting individuals’ memory, enforcing their will, and accommodating their diverse spiritual beliefs. Posthumous legal rights can also foster equality by shielding against the stigma and terror that have historically accompanied the abuse of the dead. The Constitution need not remain silent when governmental actors engage in abusive or unequal treatment in death. Understanding the dead as constitutional rights-holders opens the door to enhanced ac- countability through litigation and congressional enforcement of the Reconstruction Amendments. Beyond that, understanding the dead as rights-holders can influence the narratives that shape our collective legal, * Associate Professor, Emory Law School. I am tremendously grateful for the feedback and guidance received from Bradley Arehart, Rick Banks, Will Baude, Dean Mary Anne Bobinski, Dorothy Brown, Erica Bruchko, Emily Buss, Adam Chilton, Deborah Dinner, Mary Dudziak, Martha Fineman, Meirav Furth-Matzkin, Daniel Hemel, Joan Heminway, Todd Henderson, Steven Heyman, Timothy Holbrook, Aziz Huq, Daniel LaChance, Alison LaCroix, Genevieve Lakier, Matthew Lawrence, Kay Levine, Jonathan S. -

Death Anxiety Among Handicapped and Normal Women Dr

The International Journal of Indian Psychology ISSN 2348-5396 (e) | ISSN: 2349-3429 (p) Volume 2, Issue 3, Paper ID: B00395V2I32015 http://www.ijip.in | April to June 2015 Death Anxiety among Handicapped and Normal Women Dr. D. A. Dadhania1 ABSTRACT: The present study is main aim was to comparative study of death anxiety among handicapped and normal women. The study was conducted on a sample consisted of 90 people out which 45 were handicapped women and 45 normal women in Jamnagar city (Gujarat). Collected data from the women as Death Anxiety scale – by Prof. K. D. Broata. The obtained data were analyzed though „t‟ test to know the mean difference between the two groups handicapped women and normal women. The results show that there is significant difference in the death anxiety level of the normal women and handicapped women. Keywords: Death Anxiety, handicapped Death anxiety is the morbid, abnormal or persistent fear of one's own mortality. One definition of death anxiety is a "feeling of dread, apprehension or solicitude (anxiety) when one thinks of the process of dying, or ceasing to „be‟". It is also referred to as than to phobia (fear of death), and is distinguished from necrophilia, which is a specific fear of dead or dying persons and/or things (i.e. others who are dead or dying, not one's own death or dying). Lower ego integrity, more physical problems, and more psychological problems are predictive of higher levels of death anxiety in elderly people. Death anxiety refers the fear of and anxiety related to the anticipation, and awareness, of dying, death, and nonexistence.