July / August 2007

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 EDUCATION New Dimensions PUBLISHERS' NOTE Swami

EDUCATION New Dimensions PUBLISHERS' NOTE Swami Vivekananda declares that education is the panacea for all our evils. According to him `man-making' or `character-building' education alone is real education. Keeping this end in view, the centres of the Ramakrishna Math and the Ramakrishna Mission have been running a number of institutions solely or partly devoted to education. The Ramakrishna Math of Bangalore (known earlier as Sri Ramakrishna Ashrama) started the `Sri Ramakrishna Vidyarthi Mandiram' in 1943, as a hostel for college boys wherein the inculcating of moral and spiritual values in the minds of the inmates was given the primary importance. The hostel became popular very soon and the former inmates who are now occupying important places in public life, still remember their life at the hostel. In 1958, the Vidyarthi Mandiram was shifted to its own newly built, spacious and well- designed, premises. In 1983, the Silver Jubilee celebrations were held in commemoration of this event. During that period a Souvenir entitled ``Education: New Dimensions'' was brought out. Very soon, the copies were exhausted. However, the demand for the same, since it contained many original and thought-provoking articles, went on increasing. We are now bringing it out as a book with some modifications. Except the one article of Albert Einstein which has been taken from an old journal, all the others are by eminent monks of the Ramakrishna Order who have contributed to the field of education, in some way or the other. We earnestly hope that all those interested in the education of our younger generation, especially those in the teaching profession, will welcome this publication and give wide publicity to the ideas contained in it. -

Reminiscences of Swami Prabuddhananda

Reminiscences of Swami Prabuddhananda India 2010 These precious memories of Swami Prabuddhanandaji are unedited. Since this collection is for private distribution, there has been no attempt to correct or standardize the grammar, punctuation, spelling or formatting. The charm is in their spontaneity and the heartfelt outpouring of appreciation and genuine love of this great soul. May they serve as an ongoing source of inspiration. Memories of Swami Prabuddhananda MEMORIES OF SWAMI PRABUDDHANANDA RAMAKRISHNA MATH Phone PBX: 033-2654- (The Headquarters) 1144/1180 P.O. BELUR MATH, DIST: FAX: 033-2654-4346 HOWRAH Email: [email protected] WEST BENGAL : 711202, INDIA Website: www.belurmath.org April 27, 2015 Dear Virajaprana, I am glad to receive your e-mail of April 24, 2015. Swami Prabuddhanandaji and myself met for the first time at the Belur Math in the year 1956 where both of us had come to receive our Brahmacharya-diksha—he from Bangalore and me from Bombay. Since then we had close connection with each other. We met again at the Belur Math in the year 1960 where we came for our Sannyasa-diksha from Most Revered Swami Sankaranandaji Maharaj. I admired his balanced approach to everything that had kept the San Francisco centre vibrant. In 2000 A.D. he had invited me to San Francisco to attend the Centenary Celebrations of the San Francisco centre. He took me also to Olema and other retreats on the occasion. Once he came just on a visit to meet the old Swami at the Belur Math. In sum, Swami Prabuddhanandaji was an asset to our Order, and his leaving us is a great loss. -

Halasuru Math Book List

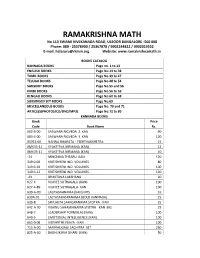

RAMAKRISHNA MATH No.113 SWAMI VIVEKANADA ROAD, ULSOOR BANGALORE -560 008 Phone: 080 - 25578900 / 25367878 / 9902244822 / 9902019552 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.ramakrishnamath.in BOOKS CATALOG KANNADA BOOKS Page no. 1 to 13 ENGLISH BOOKS Page No.14 to 38 TAMIL BOOKS Page No.39 to 47 TELUGU BOOKS Page No.48 to 54 SANSKRIT BOOKS Page No.55 and 56 HINDI BOOKS Page No.56 to 59 BENGALI BOOKS Page No.60 to 68 SUBSIDISED SET BOOKS Page No.69 MISCELLANEOUS BOOKS Page No. 70 and 71 ARTICLES(PHOTOS/CD/DVD/MP3) Page No.72 to 80 KANNADA BOOKS Book Price Code Book Name Rs. 002-6-00 SASWARA RIGVEDA 2 KAN 90 003-4-00 SASWARA RIGVEDA 3 KAN 120 05951-00 NANNA BHARATA - TEERTHAKSHETRA 15 0MK35-11 VYAKTITVA NIRMANA (KAN) 12 0MK35-11 VYAKTITVA NIRMANA (KAN) 10 -24 MINCHINA THEARU KAN 120 349.0-00 KRITISHRENI IND. VOLUMES 80 349.0-10 KRITISHRENI IND. VOLUMES 100 349.0-12 KRITISHRENI IND. VOLUMES 120 -43 BHAKTANA LAKSHANA 20 627-4 VIJAYEE SUTRAGALU (KAN) 100 627-4-89 VIJAYEE SUTRAGALA- KAN 100 639-A-00 LALITASAHNAMA (KAN) MYS 16 639A-01 LALTASAHASRANAMA (BOLD KANNADA) 25 639-B SRI LALITA SAHASRANAMA STOTRA - KAN 25 642-A-00 VISHNU SAHASRANAMA STOTRA - KAN BIG 25 648-7 LEADERSHIP FORMULAS (KAN) 100 649-5 EMOTIONAL INTELLIGENCE (KAN) 100 663-0-08 VIDYARTHI VIJAYA - KAN 100 715-A-00 MAKKALIGAGI SACHITRA SET 250 825-A-00 BADHUKUVA DHARI (KAN) 50 840-2-40 MAKKALA SRI KRISHNA - 2 (KAN) 40 B1039-00 SHIKSHANA RAMABANA 6 B4012-00 SHANDILYA BHAKTI SUTRAS 75 B4015-03 PHIL. -

Remembering Sri Sarada Devi's Disciple

Copyright 2010 by Esther Warkov All rights reserved First printed in 2010 Cover Design by Gregory Fields No portion of this book or accompanying DVD may be reproduced anywhere (including the internet) or used in any form, or by any means (written, electronic, mechanical, or other means now known or hereafter invented including photocopying, duplicating, and recording) without prior written permission from the author/publisher. Exceptions are made for brief excerpts used in published reviews. Photographs on the accompanying disc may be printed for home use only. The song appearing on the accompanying disc may be duplicated and used for non-commercial purposes only. ISBN 978-0-578-04660-0 To order copies of this publication please visit Compendium Publications www.compendiumpublications.com or contact the author at [email protected] (Seattle, WA, USA) Table of Contents Introduction and Acknowledgements v About the Contributors ix Remembrances from Monastic Devotees Swami Yogeshananda 3 Swami Damodarananda “Swami Aseshanandaji: Humble and Inspiring‖ 8 Swami Manishananda “Reminiscences of Swami Aseshananda‖ 11 Pravrajika Gayatriprana 15 Pravrajika Brahmaprana “Reminiscences of Swami Aseshananda‖ 25 Swami Harananda 33 Pravrajika Sevaprana 41 Swami Tathagatananda ―Reminiscences of Revered Swami Aseshanandaji‖ 43 Swami Brahmarupananda “Swami Aseshananda As I Saw Him‖ 48 Anonymous Pravrajika 50 Vimukta Chaitanya 51 Six Portraits of Swami Aseshananda Michael Morrow (Vijnana) 55 Eric Foster 60 Anonymous ―Initiation Accounts‖ 69 Alex S. Johnson ―The Influence and Example of a Great Soul‖ 72 Ralph Stuart 74 Jon Monday (Dharmadas) ―A Visit with a Swami in America‖ 88 The Early Years: 1955-1969 Vera Edwards 95 Marina Sanderson 104 Robert Collins, Ed. -

THE LION of VEDANTA a Cultural and Spiritual Monthly of the Ramakrishna Order Since 1914

nd Price: ` 10 YEAR OF PUBLICATION 㼀㼔㼑㻌㼂㼑㼐㼍㼚㼠㼍㻌㻷㼑㼟㼍㼞㼕 THE LION OF VEDANTA A Cultural and Spiritual Monthly of the Ramakrishna Order since 1914 Ramakrishna Advaita Ashrama, Kalady, Kerala July 2015 2 India's Timeless Wisdom Knowledge is the (real) wealth of a man while staying in foreign lands. His intelligence is his only wealth in adversities. His righteous behaviour is his wealth in other world (after the death). Good conduct (however) is the wealth every where. —A Traditional saying Sunrise on Periyar River, Kalady, Kerala Editor: SWAMI ATMASHRADDHANANDA Managing Editor: SWAMI GAUTAMANANDA PrintedPri and published by Swami Vimurtananda on behalf of Sri Ramakrishna Math Trustst 2 fromThe No.31, RamakrishnaV edanta KMathesari Road, ~ Mylapore, ~ JULY Chennai 2015 - 4 and Printed at Sri Ramakrishna Printing Press, No.31 Ramakrishna Math Road, Mylapore, Chennai - 4. Ph: 044 - 24621110 㼀㼔㼑㻌㼂㼑㼐㼍㼚㼠㼍㻌㻷㼑㼟㼍㼞㼕 102nd YEAR OF PUBLICATION VOL. 102, No. 7 ISSN 0042-2983 A CULTURAL AND SPIRITUAL MONTHLY OF THE RAMAKRISHNA ORDER Started at the instance of Swami Vivekananda in 1895 as Brahmavâdin, it assumed the name The Vedanta Kesari in 1914. For free edition on the Web, please visit: www.chennaimath.org CONTENTS JULY 2015 Gita Verse for Reflection 245 Editorial The Story of Desire 246 Articles Learning to Contribute: An Approach to Karma Yoga 255 V Srinivas Balaram Mandir and Swami Brahmananda 260 Hiranmoy Mukherjee Dissolving Boundaries 264 Pravrajika Virajaprana Four Encounters with Surdas 272 N. Krishnaswamy Story God Exists And We Can See Him—Two -

Readings on the Spiritual Teachings of Swami Brahmananda

READINGS ON SWAMI BRAHMANANDA’S SPIRITUAL TEACHINGS by Swami Yatiswarananda Reference is to: SPIRITUAL TEACHINGS OF SWAMI BRAHMANANDA (with a foreword by Sister Devamata) 1931, Sri Ramakrishna Math, Madras Republished 1978, under title of THE ETERNAL COMPANION SPIRITUAL TEACHINGS OF SWAMI BRAHMANANDA [Including the biographical material of Swami Prabhavananda’s 1944 ETERNAL COMPANION] Offered to: The Participants, EUROPEAN VEDANTA CONFERENCE Brabant, Holland 1993 Published by: John Manetta Beles 28 (Koukaki) GR 117 41 Athens, Greece Phone +30 210 923 4682 e-mail: [email protected] Printed in Athens, Greece April, 1993 Printed to CD August 2004 Processed with: Ventura Publisher Typeset in Helvetica 10/12 PUBLISHER’S NOTE Dear Friends, We are happy to share with you, in the original format, the complete text of Swami Yatiswarananda’s READINGS ON SWAMI BRAHMAN- ANDA’S SPIRITUAL TEACHINGS, as delivered from November 21st, 1933 through January 7th, 1934, at Wiesbaden, Germany, to an intimate group of European students he had begun intensively training. These READINGS in English—the first of a series, copies of which were preserved by Vedanta devotees in Germany, have never been pub- lished in their entirety. Apart from a few extracts which appeared in VEDANTA FOR EAST & WEST (Bourne End’s magazine), only READ- INGS 1 through 17 (out of 48) were appended in French to Jean Herbert’s translation of the original SPIRITUAL TEACHINGS OF SWAMI BRAHM- ANANDA1 — first published in 1949 by Editions Derain, Lyons, France, under the title of: ‘Swami Brahmananda: DISCIPLINE MONASTIQUE’. We are grateful to Kurt Friedrichs of Hamburg, a disciple of the Swami, for sharing his copy of these READINGS with us. -

Essentials of Meditative Life 5

SwamiYatiswarananda ESSENTIALS OF MEDITATIVE LIFE MEDITATION&SPIRITUALLIFE Chapter18 Publishedby SriRamakrishnaMath BullTempleRoad Bangalore560019,India FirstEdition1979 (EditedversionofrecordinginaudiosectionoftheCD) uu Read:A5_READ.pdffileinAdobeReader ClickonContentstojumptosubjects Enlarge/ReducetextviaCtrl+/-(Keypad) ReflowenlargedtextviaCtrl4(Keypad) InvertvideocoloursviaCtrlK:Accessibility Print:A4_PRINT.pdffilefromAdobeReader (Printodd/evenasbookletonA4bothsides) ` VEDANTASTUDYCIRCLE Athens,Greece–2003 -2012 Sourceofthetext : MEDITATION&SPIRITUALLIFE Firstpublishedin1979by: SriRamakrishnaMath BullTempleRoad Bangalore560019India “This book, a compilation of class-talks given by Swami Yatiswarananda to groups of earnest spiritual aspirants in Eu- rope, the USA and India is a practical manual of spiritual life, with special emphasis on meditation. Though designed for the use of religious people in general, it is specially intended for those who sincerely practise prayer, Japa [repetition of holy name] and meditation and are eager to attain some spiritual fulfilment. The true seeker of Truth will find in it simple but valu- able guidance regarding preliminary preparations, different techniques of meditation, various obstacles that are to be over- come, the nature of genuine spiritual experiences, and other important details of meditative life which can otherwise be gainedonlythroughintimatecontactwithanilluminedGuru.” (Fromtheinsideflapofthecover) Thebookwascompiledandeditedby SwamiBhajanananda Theaudioversionisfromatape-reel wegotinBangalorein1979 -

Magazine Articles November / December 2007

Magazine Articles November / December 2007 1. Divine Wisdom 2. Editorial 3. Conversations with Swami Turiyananda Swami Raghavananda 4. Questions and Answers - Swami Ghanananda 5. Transformation and Transcendence - Swami Bhajanananda 6. Lessons of Life - Swami Vidyatmananda 7. Seeds (continued) - Swami Yatiswarananda 8. Book Review - John Phillips Divine Wisdom Master: "One cannot obtain the Knowledge of Brahman unless one is extremely cautious about women. Therefore it is very difficult for those who live in the world to get such Knowledge. However clever you may be, you will stain your body if you live in a sooty room. The company of a young woman evokes lust even in a lustless man. "But it is not so harmful for a householder who follows the path of knowledge to enjoy conjugal happiness with his own wife now and then. He may satisfy his sexual impulse like any other natural impulse. Yes, you may enjoy a sweetmeat once in a while. (Mahimacharan laughs.) It is not so harmful for a householder. "But it is extremely harmful for a sannyasi. He must not look even at the portrait of a woman. A monk enjoying a woman is like a man swallowing the spittle he has already spat out. A sannyasi must not sit near a woman and talk to her, even if she is intensely pious. No, he must not talk to a woman even though he may have controlled his passion. "A sannyasi must renounce both 'woman' and 'gold'. As he must not look even at the portrait of a woman, so also he must not touch gold, that is to say, money. -

Readings on the Gospel of Sri Ramakrishna

SwamiYatiswarananda READINGS ON THE GOSPEL OF SRI RAMAKRISHNA VolumeI(Madras1911) VolumeII(Madras1922) Wiesbaden,Germany April26,1934throughJanuary9,1935 VedantaStudyCircle Athens,Greece 1994 Publishedby: JohnManetta Beles28(Koukaki) GR11741Athens,Greece Phone:[+30]2109234682 email: [email protected] website: www.vedanta.gr Printedin Athens,Greece Printing 1st—September,1994 PrintedtoCD—August2004 Processedwith: VenturaPublisher Typesetin: Helvetica10/12 PUBLISHER’SNOTE Dear Friends, Further to Swami Yatiswarananda’s READINGS on SWAMI BRAH- MANANDA’S SPIRITUAL TEACHINGS, and the READINGS on the VEDANTASARA, the NARADA BHAKTI SUTRAS, the DRG-DRSYA VIVEKA and the BHAGAVAD-GITA, we are happy to share with you Swami Yatiswarananda’s READINGS ON THE GOSPEL OF SRI RA- MAKRISHNA VOL. I & II, the notes of class-talks delivered at Wies- baden, Germany, to an intimate group of European students, from April 25, 1934 through January 9, 1935. Our search in Germany for Readings generated between 1933-1938 had already revealed a German translation of the Gospel Readings, and we were lucky to find a copy of the English original during our 1993 search at Sri Ramakrishna Math, Bangalore, India. Along with the original carbon copies of class-notes, there was also a slightly edited version with topic-titles, compiled by Mr. Wolfram K. Koch (Swami Yatiswarananda’s host at Wiesbaden) apparently intended for eventual publication, which we have verified and supplemented for the present publication. In view of its historical interest, we give Mr. Koch’s Introduction to the Gospel Readings, just after this Publisher’s Note. It is due to Mr. Koch’s painstaking labour that these notes were manually taken down, decoded, verified, and hard copies made for circulation among the members of the Wiesbaden Group. -

Sri Trailinga Swami Swami Amareshananda on Spiritual Practice Swami Yatiswarananda

379 SEPTEMBER- OCTOBER 2014 On Spiritual Practice Swami Yatiswarananda Sri Trailinga Swami Swami Amareshananda Divine Wisdom Teachings of Swami Vijnanananda As you think, so you become. As thoughts of love help in expanding the self, so do thoughts of anger and jealousy lead to its contraction. Unless one can restrain one's passion, anger; etc. it is impossible to get anywhere near God. If you want to control your passion, anger, etc., you have to meditate on the Master and the Holy Mother and you will then be free from all degrading thoughts. You better leave debates and arguments alone. We have got a brain of very limited capacity; and for realizing God, all this hair-splitting is of no use. What you require is burning faith in Him. In order to be firmly established in that faith, you may raise one or two valid points, but nothing more. Our arguments are just like armchair discussions; they lead us nowhere. We argue about God and then go home and lie down in bed. That is not religion, and it does not contribute to peace of mind. Faith is the foundation of spiritual life. Too much of ar- gumentation is of no avail . In order to be firmly established in that faith, you may raise one or two valid points, but nothing more. Unless you have faith, arguments and discussions will only cloud the issue and create confusion. When, therefore, our entire existence depends on Him, why should we form an attachment for worldly things? World- ly attachments draw people away from God and scorch them in the wildfire of the world. -

Concentration & Meditation

Swami Bhajanananda Concentration and Meditation An in-depth look at the theory and practice of Hindu meditation, including an overview of Yoga psychology. Contents 1.ConcentrationandMeditation OrdinaryConcentrationandMeditation................................................4 Prayer,Worship,Meditation ................................................................10 MeditationDuringtheEarlyStages.....................................................11 2.WhatTrueMeditationIs PsychologicalBasisofMeditation.......................................................17 3.DissociationandConflict TwoTypesofSamskaras ....................................................................25 ControloftheVrittis .............................................................................26 PurificationofSamskaras ....................................................................27 TheActionofSamskaras.....................................................................28 TheFiveStatesofSamskaras .............................................................30 StagesinPurification ...........................................................................32 DissociationandtheThreeStatesofConsciousness ........................32 4.TheFiveStatesoftheMind TheFiveStatesoftheMind.................................................................33 FunctionsoftheMind ..........................................................................35 TheWillandItsFunction .....................................................................37 StagesinConcentration ......................................................................40 -

Readings on the Gospel of Sri Ramakrishna

SWAMI YATISWARANANDA IN EUROPE CD — Contents Click on any of the PDF files below to VIEW it [While viewing, Click HOME KEY to return to this page] Introduction Spiritual Instructions - (pdf) >>> CD_Intro (pdf) <<< The Spiritual Path - (pdf) READINGS: 1933–38 CLASS-NOTES Aids to Meditation - (pdf) The Ancient and Eternal Battle - (pdf) 1. Spiritual Teachings of Swami Brahmananda - (pdf) The Way to the Divine - (pdf) 2. Vedantasara - (pdf) Vedanta Work in Europe [incl. 1933-34 Diaries] - (pdf) 3. Narada Bhakti Sutras - (pdf) Vedanta Work in Europe - France - (pdf) 4. Bhagavad Gita - (pdf) Vedanta Work in USA [1941 Diary] - (pdf) 5. Gospel of Sri Ramakrishna The Ramakrishna-Vedanta Movement - (pdf) 6. Drg Drsya Viveka - (pdf) Swami Yatiswarananda - An obituary and Swami Y's 7. Sri Krishna and Uddhava - (pdf) Reminiscences of Swami Brahmananda - (pdf) 8. Passages for Daily Reading & Reflection - (pdf) Preface to "Spiritual Teachings of SwBrahm” - (pdf) “VEDANTA” Quarterly Essentials of Meditative Life (Med&SpLife.18) - (pdf) Hints for Meditation & Chart Spiritual Unfoldmt - (pdf) “Vedanta” Journal - 1937 - (pdf) “Vedanta” Journal - 1938 - (pdf) AUDIO [Open in MP3 player] Misc. Class-notes Click here for titles 1935 - Wiesbaden - (pdf) PHOTOGRAPHS: 1917–1965 1935 - St Moritz - (pdf) Photo Gallery (pdf) 1935 - Campfér: On Chastity - (pdf) BOOKLET PRINTING (On both sides of A4 paper) 1938 - St.Moritz: Readings on the Gita - (pdf) Click here for titles 1949 - St.Mortiz: Spiritual Awakening - (pdf) OTHER OTHER TEXTS Troubleshooting — Click here