Magazine Articles November / December 2007

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Life Beyond Death by Swami Abhedananda

Life Beyond Death Lectures of Swami Abhedananda A Great Yogi and Direct Disciple of Sri Ramakrishna Life Beyond Death – lovingly restored by The Spiritual Bee An e-book presentation by For more FREE books visit the website: www.spiritualbee.com Dear Reader, This book has been reproduced here from the Complete Works of Swami Abhedananda, Volume 4. The book is now in the public domain in India and the United States, because its original copyright has expired. “Life beyond Death” is a collection of lectures delivered by Swami Abhedananda in the United States. Unlike most books on the subject which mainly record encounters with ghosts and other kinds of paranormal activities, this book looks at the mystery from a soundly rational and scientific perspective. The lectures initially focus on providing rational arguments against the material theory of consciousness, which states that consciousness originates as a result of brain activity and therefore once death happens, consciousness also ends and so there is no such thing as a life beyond death. Later in the book, Swami Abhedananda also rallies against many dogmatic ideas present in Christian theology regarding the fate of the soul after death: such as the philosophies of eternal damnation to hell, resurrection of the physical body after death and the belief that the soul has a birth, but no death. In doing so Swami Abhedananda who cherished the deepest love and respect for Christ, as is evident in many of his other writings such as, “Was Christ a Yogi” (from the book How to be a Yogi?), was striving to place before his American audience, higher and more rational Vedantic concepts surrounding life beyond the grave, which have been thoroughly researched by the yogi’s of India over thousands of years. -

Conversations with Swami Turiyananda

CONVERSATIONS WITH SWAMI TURIYANANDA Recorded by Swami Raghavananda and translated by Swami Prabhavananda (This month's reading is from the Jan.-Feb., 1957 issue of Vedanta and the West.) The spiritual talks published below took place at Almora in the Himalayas during the summer of 1915 in the ashrama which Swami Turiyananda had established in cooperation with his brother-disciple, Swami Shivananda. During the course of these conversations, Swami Turiyananda describes the early days at Dakshineswar with his master, Sri Ramakrishna, leaving a fascinating record of the training of an illumined soul by this God-man of India. His memories of life with his brother-disciples at Baranagore, under Swami Vivekananda’s leadership, give a glimpse of the disciplines and struggles that formed the basis of the young Ramakrishna Order. Above all, Swami Turiyananada’s teachings in the pages that follow contain practical counsel on many aspects of religious life of interest to every spiritual seeker. Swami Turiyananda spent most of his life in austere spiritual practices. In 1899, he came to the United States where he taught Vedanta for three years, first in New York, later on the West Coast. By the example of his spirituality he greatly influenced the lives of many spiritual aspirants both in America and India. He was regarded by Sri Ramakrishna as the perfect embodiment of that renunciation which is taught in the Bhagavad Gita Swami Shivananda, some of whose talks are included below, was also a man of the highest spiritual realizations. He later became the second President of the Ramakrishna Math and Mission. -

SWAMI YOGANANDA and the SELF-REALIZATION FELLOWSHIP a Successful Hindu Countermission to the West

STATEMENT DS213 SWAMI YOGANANDA AND THE SELF-REALIZATION FELLOWSHIP A Successful Hindu Countermission to the West by Elliot Miller The earliest Hindu missionaries to the West were arguably the most impressive. In 1893 Swami Vivekananda (1863 –1902), a young disciple of the celebrated Hindu “avatar” (manifestation of God) Sri Ramakrishna (1836 –1886), spoke at the World’s Parliament of Religions in Chicago and won an enthusiastic American following with his genteel manner and erudite presentation. Over the next few years, he inaugurated the first Eastern religious movement in America: the Vedanta Societies of various cities, independent of one another but under the spiritual leadership of the Ramakrishna Order in India. In 1920 a second Hindu missionary effort was launched in America when a comparably charismatic “neo -Vedanta” swami, Paramahansa Yogananda, was invited to speak at the International Congress of Religious Liberals in Boston, sponsored by the Unitarian Church. After the Congress, Yogananda lectured across the country, spellbinding audiences with his immense charm and powerful presence. In 1925 he established the headquarters for his Self -Realization Fellowship (SRF) in Los Angeles on the site of a former hotel atop Mount Washington. He was the first Eastern guru to take up permanent residence in the United States after creating a following here. NEO-VEDANTA: THE FORCE STRIKES BACK Neo-Vedanta arose partly as a countermissionary movement to Christianity in nineteenth -century India. Having lost a significant minority of Indians (especially among the outcast “Untouchables”) to Christianity under British rule, certain adherents of the ancient Advaita Vedanta school of Hinduism retooled their religion to better compete with Christianity for the s ouls not only of Easterners, but of Westerners as well. -

1 EDUCATION New Dimensions PUBLISHERS' NOTE Swami

EDUCATION New Dimensions PUBLISHERS' NOTE Swami Vivekananda declares that education is the panacea for all our evils. According to him `man-making' or `character-building' education alone is real education. Keeping this end in view, the centres of the Ramakrishna Math and the Ramakrishna Mission have been running a number of institutions solely or partly devoted to education. The Ramakrishna Math of Bangalore (known earlier as Sri Ramakrishna Ashrama) started the `Sri Ramakrishna Vidyarthi Mandiram' in 1943, as a hostel for college boys wherein the inculcating of moral and spiritual values in the minds of the inmates was given the primary importance. The hostel became popular very soon and the former inmates who are now occupying important places in public life, still remember their life at the hostel. In 1958, the Vidyarthi Mandiram was shifted to its own newly built, spacious and well- designed, premises. In 1983, the Silver Jubilee celebrations were held in commemoration of this event. During that period a Souvenir entitled ``Education: New Dimensions'' was brought out. Very soon, the copies were exhausted. However, the demand for the same, since it contained many original and thought-provoking articles, went on increasing. We are now bringing it out as a book with some modifications. Except the one article of Albert Einstein which has been taken from an old journal, all the others are by eminent monks of the Ramakrishna Order who have contributed to the field of education, in some way or the other. We earnestly hope that all those interested in the education of our younger generation, especially those in the teaching profession, will welcome this publication and give wide publicity to the ideas contained in it. -

Reminiscences of Swami Prabuddhananda

Reminiscences of Swami Prabuddhananda India 2010 These precious memories of Swami Prabuddhanandaji are unedited. Since this collection is for private distribution, there has been no attempt to correct or standardize the grammar, punctuation, spelling or formatting. The charm is in their spontaneity and the heartfelt outpouring of appreciation and genuine love of this great soul. May they serve as an ongoing source of inspiration. Memories of Swami Prabuddhananda MEMORIES OF SWAMI PRABUDDHANANDA RAMAKRISHNA MATH Phone PBX: 033-2654- (The Headquarters) 1144/1180 P.O. BELUR MATH, DIST: FAX: 033-2654-4346 HOWRAH Email: [email protected] WEST BENGAL : 711202, INDIA Website: www.belurmath.org April 27, 2015 Dear Virajaprana, I am glad to receive your e-mail of April 24, 2015. Swami Prabuddhanandaji and myself met for the first time at the Belur Math in the year 1956 where both of us had come to receive our Brahmacharya-diksha—he from Bangalore and me from Bombay. Since then we had close connection with each other. We met again at the Belur Math in the year 1960 where we came for our Sannyasa-diksha from Most Revered Swami Sankaranandaji Maharaj. I admired his balanced approach to everything that had kept the San Francisco centre vibrant. In 2000 A.D. he had invited me to San Francisco to attend the Centenary Celebrations of the San Francisco centre. He took me also to Olema and other retreats on the occasion. Once he came just on a visit to meet the old Swami at the Belur Math. In sum, Swami Prabuddhanandaji was an asset to our Order, and his leaving us is a great loss. -

Swami Dayatmananda)

Magazine Articles July / August 2009 1. Divine Wisdom 2. Editorial: Saints as Beacon Lights (Swami Dayatmananda) 3. Saint Namadeva - Swami Lokeswarananda 4. Pathways of Realization (cont.) - Clement James Knott 5. Conversations with Swami Turiyananda (cont.) - Swami Raghavananda 6. Indian Thought and Carmelite Spirituality - Swami Siddheshwarananda 7. Leaves of an Ashrama 30: The Truly Great as Friends and Models - Swami Vidyatmananda 8. Book Reviews - John Phillips Divine Wisdom MANILAL: "What is our duty?" MASTER: "To remain somehow united with God. There are two ways: karmayoga and manoyoga. Householders practise yoga through karma, the performance of duty. There are four stages of life: brahmacharya, garhasthya, vanaprastha, and sannyas. Sannyasis must renounce those karmas which are performed with special ends in view; but they should perform the daily obligatory karmas, giving up all desire for results. Sannyasis are united with God by such karmas as the acceptance of the staff, the receiving of alms, going on pilgrimage, and the performance of worship and japa."It doesn't matter what kind of action you are engaged in. You can be united with God through any action provided that, performing it, you give up all desire for its result. "There is the other path: manoyoga. A yogi practising this discipline doesn't show any outward sign. He is inwardly united with God. Take Jadabharata and Sukadeva, for instance. There are many other yogis of this class, but these two are well known. They shave neither hair nor beard. "All actions drop away when a man reaches the stage of the paramahamsa. He always remembers the ideal and meditates on it. -

Thevedanta Kesari February 2020

1 TheVedanta Kesari February 2020 1 The Vedanta Kesari The Vedanta Cover Story Sri Ramakrishna : A Divine Incarnation page 11 A Cultural and Spiritual Monthly 1 `15 February of the Ramakrishna Order since 1914 2020 2 Mylapore Rangoli competition To preserve and promote cultural heritage, the Mylapore Festival conducts the Kolam contest every year on the streets adjoining Kapaleswarar Temple near Sri Ramakrishna Math, Chennai. Regd. Off. & Fact. : Plot No.88 & 89, Phase - II, Sipcot Industrial Complex, Ranipet - 632 403, Tamil Nadu. Editor: SWAMI MAHAMEDHANANDA Phone : 04172 - 244820, 651507, PRIVATE LIMITED Published by SWAMI VIMURTANANDA, Sri Ramakrishna Math, Chennai - 600 004 and Tele Fax : 04172 - 244820 (Manufacturers of Active Pharmaceutical Printed by B. Rajkumar, Chennai - 600 014 on behalf of Sri Ramakrishna Math Trust, Chennai - 600 004 and Ingredients and Intermediates) E-mail : [email protected] Web Site : www.svisslabss.net Printed at M/s. Rasi Graphics Pvt. Limited, No.40, Peters Road, Royapettah, Chennai - 600014. Website: www.chennaimath.org E-mail: [email protected] Ph: 6374213070 3 THE VEDANTA KESARI A Cultural and Spiritual Monthly of The Ramakrishna Order Vol. 107, No. 2 ISSN 0042-2983 107th YEAR OF PUBLICATION CONTENTS FEBRUARY 2020 ory St er ov C 11 Sri Ramakrishna: A Divine Incarnation Swami Tapasyananda 46 20 Women Saints of FEATURES Vivekananda Varkari Tradition Rock Memorial Atmarpanastuti Arpana Ghosh 8 9 Yugavani 10 Editorial Sri Ramakrishna and the A Curious Boy 18 Reminiscences Pilgrimage Mindset 27 Vivekananda Way Gitanjali Murari Swami Chidekananda 36 Special Report 51 Pariprasna Po 53 The Order on the March ck et T a le 41 25 s Sri Ramakrishna Vijayam – Poorva: Magic, Miracles Touching 100 Years and the Mystical Twelve Lakshmi Devnath t or ep R l ia c e 34 31 p S Editor: SWAMI MAHAMEDHANANDA Published by SWAMI VIMURTANANDA, Sri Ramakrishna Math, Chennai - 600 004 and Printed by B. -

Ramakrishna-Vedanta in Southern California: from Swami Vivekananda to the Present

Ramakrishna-Vedanta in Southern California: From Swami Vivekananda to the Present Appendix I: Ramakrishna-Vedanta Swamis in Southern California and Affiliated Centers (1899-2017) Appendix II: Ramakrishna-Vedanta Swamis (1893-2017) Appendix III: Presently Existing Ramakrishna-Vedanta Centers in North America (2017) Appendix IV: Ramakrishna-Vedanta Swamis from India in North America (1893-2017) Bibliography Alphabetized by Abbreviation Endnotes Appendix 12/13/2020 Page 1 Ramakrishna-Vedanta in Southern California: From Swami Vivekananda to the Present Appendix I: Ramakrishna Vedanta Swamis Southern California and Affiliated Centers (1899-2017)1 Southern California Vivekananda (1899-1900) to India Turiyananda (1900-02) to India Abhedananda (1901, 1905, 1913?, 1914-18, 1920-21) to India—possibly more years Trigunatitananda (1903-04, 1911) Sachchidananda II (1905-12) to India Prakashananda (1906, 1924)—possibly more years Bodhananda (1912, 1925-27) Paramananda (1915-23) Prabhavananda (1924, 1928) _______________ La Crescenta Paramananda (1923-40) Akhilananda (1926) to Boston _______________ Prabhavananda (Dec. 1929-July 1976) Ghanananda (Jan-Sept. 1948, Temporary) to London, England (Names of Assistant Swamis are indented) Aseshananda (Oct. 1949-Feb. 1955) to Portland, OR Vandanananda (July 1955-Sept. 1969) to India Ritajananda (Aug. 1959-Nov. 1961) to Gretz, France Sastrananda (Summer 1964-May 1967) to India Budhananda (Fall 1965-Summer 1966, Temporary) to India Asaktananda (Feb. 1967-July 1975) to India Chetanananda (June 1971-Feb. 1978) to St. Louis, MO Swahananda (Dec. 1976-2012) Aparananda (Dec. 1978-85) to Berkeley, CA Sarvadevananda (May 1993-2012) Sarvadevananda (Oct. 2012-) Sarvapriyananda (Dec. 2015-Dec. 2016) to New York (Westside) Resident Ministers of Affiliated Centers: Ridgely, NY Vivekananda (1895-96, 1899) Abhedananda (1899) Turiyananda (1899) _______________ (Horizontal line means a new organization) Atmarupananda (1997-2004) Pr. -

019Mar05.Pdf(1M)

JANUARY 2005 MARCH 2005 Volume 3 Number 3 Thus Spake ... "Never quarrel about religion. All quarrels and disputations concerning religion simply show that spirituality is not present. Religious quarrels are always over the husks. When purity, when spirituality goes, leaving the soul dry, quarrels begin, and not before." ... Swami Vivekananda "He who believes in one God and the life beyond, let him speak what is good or remain silent." ... Prophet Muhammad The February Retreat In This Issue: “Naren has Accepted Mother Kali” • Thus Spake ... page 1 • Monthly Calendar ... page 1 The monthly retreat at Zushi Centre on • February Retreat ... page 1 Sunday, February 20, celebrated the • News from Headquarters ... page 2 143rd birth anniversary of Swami • Retreat - Afternoon Session ... page 2 Vivekananda. With a ringing of the bell, • Thought of the Month ... page 4 members and guests quietly assembled in • A Story to Remember ... page 6 the main shrine where Swami Medhasananda conducted a brief worship. • Retreat Photo Collage ... page 7 Afterwards, focus shifted to the adjacent meeting room for the morning session talk Monthly Calendar which began with Vedic chanting and Birthdays readings in Japanese and English from • • Swami Vivekananda's talks on Raja Yoga. Sri Sri Ramakrishna Deva Saturday, March 12 The swami offered his welcoming Swami Yogananda comments in both English and Japanese, Thursday, March 29 as our usual interpreter, Mr. Ito, had yet to arrive, but upon surveying the room, • Kyokai Events • determined that it would be more practical March Retreat to proceed in Japanese only, since the majority in attendance were Japanese and Sri Sri Ramakrishna Deva most of the others were competent in the Birthday Celebration SUNDAY - March 20 language. -

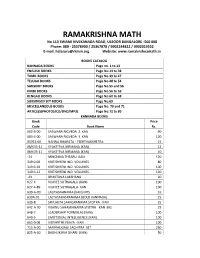

Halasuru Math Book List

RAMAKRISHNA MATH No.113 SWAMI VIVEKANADA ROAD, ULSOOR BANGALORE -560 008 Phone: 080 - 25578900 / 25367878 / 9902244822 / 9902019552 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.ramakrishnamath.in BOOKS CATALOG KANNADA BOOKS Page no. 1 to 13 ENGLISH BOOKS Page No.14 to 38 TAMIL BOOKS Page No.39 to 47 TELUGU BOOKS Page No.48 to 54 SANSKRIT BOOKS Page No.55 and 56 HINDI BOOKS Page No.56 to 59 BENGALI BOOKS Page No.60 to 68 SUBSIDISED SET BOOKS Page No.69 MISCELLANEOUS BOOKS Page No. 70 and 71 ARTICLES(PHOTOS/CD/DVD/MP3) Page No.72 to 80 KANNADA BOOKS Book Price Code Book Name Rs. 002-6-00 SASWARA RIGVEDA 2 KAN 90 003-4-00 SASWARA RIGVEDA 3 KAN 120 05951-00 NANNA BHARATA - TEERTHAKSHETRA 15 0MK35-11 VYAKTITVA NIRMANA (KAN) 12 0MK35-11 VYAKTITVA NIRMANA (KAN) 10 -24 MINCHINA THEARU KAN 120 349.0-00 KRITISHRENI IND. VOLUMES 80 349.0-10 KRITISHRENI IND. VOLUMES 100 349.0-12 KRITISHRENI IND. VOLUMES 120 -43 BHAKTANA LAKSHANA 20 627-4 VIJAYEE SUTRAGALU (KAN) 100 627-4-89 VIJAYEE SUTRAGALA- KAN 100 639-A-00 LALITASAHNAMA (KAN) MYS 16 639A-01 LALTASAHASRANAMA (BOLD KANNADA) 25 639-B SRI LALITA SAHASRANAMA STOTRA - KAN 25 642-A-00 VISHNU SAHASRANAMA STOTRA - KAN BIG 25 648-7 LEADERSHIP FORMULAS (KAN) 100 649-5 EMOTIONAL INTELLIGENCE (KAN) 100 663-0-08 VIDYARTHI VIJAYA - KAN 100 715-A-00 MAKKALIGAGI SACHITRA SET 250 825-A-00 BADHUKUVA DHARI (KAN) 50 840-2-40 MAKKALA SRI KRISHNA - 2 (KAN) 40 B1039-00 SHIKSHANA RAMABANA 6 B4012-00 SHANDILYA BHAKTI SUTRAS 75 B4015-03 PHIL. -

Holy Mother Sri Sarada Devi

american vedantist Volume 15 No. 3 • Fall 2009 Sri Sarada Devi’s house at Jayrambati (West Bengal, India), where she lived for most of her life/Alan Perry photo (2002) Used by permission Holy Mother, Sri Sarada Devi Vivekananda on The First Manifestation — Page 3 STATEMENT OF PURPOSE A NOTE TO OUR READERS American Vedantist (AV)(AV) is dedicated to developing VedantaVedanta in the West,West, es- American Vedantist (AV)(AV) is a not-for-profinot-for-profi t, quarterly journal staffedstaffed solely by pecially in the United States, and to making The Perennial Philosophy available volunteers. Vedanta West Communications Inc. publishes AV four times a year. to people who are not able to reach a Vedanta center. We are also dedicated We welcome from our readers personal essays, articles and poems related to to developing a closer community among Vedantists. spiritual life and the furtherance of Vedanta. All articles submitted must be typed We are committed to: and double-spaced. If quotations are given, be prepared to furnish sources. It • Stimulating inner growth through shared devotion to the ideals and practice is helpful to us if you accompany your typed material by a CD or fl oppy disk, of Vedanta with your text fi le in Microsoft Word or Rich Text Format. Manuscripts also may • Encouraging critical discussion among Vedantists about how inner and outer be submitted by email to [email protected], as attached fi les (preferred) growth can be achieved or as part of the e mail message. • Exploring new ways in which Vedanta can be expressed in a Western Single copy price: $5, which includes U.S. -

Life of Swami Brahmananda (Raja Maharaj)

Direct Disciples of Sri Ramakrishna Life of Swami Brahmananda (Raja Maharaj) (1863-1922) "Mother, once I asked Thee to give me a companion just like myself. Is that why Thou hast given me Rakhal?" -- Sri Ramakrishna (conversing with the Divine Mother) "Ah, what a nice character Rakhal has developed! Look at his face and every now and then you will notice his lips moving. Inwardly he repeats the name of God, and so his lips move. "Youngsters like him belong to the class of the ever-perfect. They are born with God- Consciousness. No sooner do they grow a little older than they realize the danger of coming in contact with the world. There is the parable of the homa bird in the Vedas. The bird lives high up in the sky and never descends to earth. It lays its eggs in the sky, and the egg begins to fall. But the bird lives in such a high region that the egg hatches while falling. The fledgling comes out and continues to fall. But it is still so high that while falling it grows wings and its eyes open. Then the young bird perceives that it is dashing down toward the earth and will be instantly killed. The moment it sees the ground, it turns and shoots up toward its mother in the sky. Then its one goal is to reach its mother. "Youngsters like Rakhal are like that bird. From their very childhood they are afraid of the world, and their one thought is how to reach the Mother, how to realize God." -- Sri Ramakrishna Swami Brahmananda (1863-1922), whose life and teachings are recorded in this, was in a mystical sense, an 'eternal companion' of the Great Master, Sri Ramakrishna.