Designing the German Monetary Union in 19901

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

German-Russian Natural Gas Relations in the Context of a Common European Energy Policy

Graduate School of Social Sciences (GSSS) German-Russian natural gas relations in the context of a common European energy policy Thesis to obtain the academic title of Master of Science (MS) in the program Political Science (International Relations) Academic year 2018/2019 Date of submission: June 21st 2019 Author: Caspar M. Henke (12299804) Supervisor: Dr. Mehdi P. Amineh Second Reader: Dr. Henk W. Houweling Research Project: The Political Economy of Energy Abstract This thesis analyses the interwoven commercial and political fabric of German-Russian natural gas relations. A theoretical lens that combines liberalist interdependence theory and the critical theoretical concepts of the state-society complex and social networks against the background of selected energy security dimensions will be employed. It will be argued that in order to assess the prospects for a common European Union energy policy, it is crucial to understand the importance of social forces and external relations shaping the energy policy of EU member states vis-á-vis the Russian Federation. It will be highlighted how the different perceptions of Russian natural gas as a political tool and a commercial commodity have resulted in different actors taking the lead in the natural gas strategies of the European Commission, the Central and Eastern European member states, and Germany. Portraying the Russian state-society complex of natural gas, it will be concluded that the German commercial-led approach is not compatible with a European Union energy policy that responds to the geopolitical threats of Russian gas perceived by other member states. Key words: Natural Gas, Russia, Germany, European Union, State-society complex 2 AcKnowledgements I would like to express my sincere gratitude to my thesis supervisor Dr. -

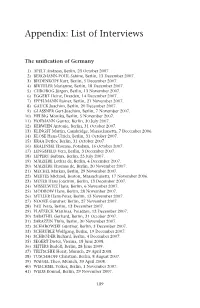

Appendix: List of Interviews

Appendix: List of Interviews The unification of Germany 1) APELT Andreas, Berlin, 23 October 2007. 2) BERGMANN-POHL Sabine, Berlin, 13 December 2007. 3) BIEDENKOPF Kurt, Berlin, 5 December 2007. 4) BIRTHLER Marianne, Berlin, 18 December 2007. 5) CHROBOG Jürgen, Berlin, 13 November 2007. 6) EGGERT Heinz, Dresden, 14 December 2007. 7) EPPELMANN Rainer, Berlin, 21 November 2007. 8) GAUCK Joachim, Berlin, 20 December 2007. 9) GLÄSSNER Gert-Joachim, Berlin, 7 November 2007. 10) HELBIG Monika, Berlin, 5 November 2007. 11) HOFMANN Gunter, Berlin, 30 July 2007. 12) KERWIEN Antonie, Berlin, 31 October 2007. 13) KLINGST Martin, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 7 December 2006. 14) KLOSE Hans-Ulrich, Berlin, 31 October 2007. 15) KRAA Detlev, Berlin, 31 October 2007. 16) KRALINSKI Thomas, Potsdam, 16 October 2007. 17) LENGSFELD Vera, Berlin, 3 December 2007. 18) LIPPERT Barbara, Berlin, 25 July 2007. 19) MAIZIÈRE Lothar de, Berlin, 4 December 2007. 20) MAIZIÈRE Thomas de, Berlin, 20 November 2007. 21) MECKEL Markus, Berlin, 29 November 2007. 22) MERTES Michael, Boston, Massachusetts, 17 November 2006. 23) MEYER Hans Joachim, Berlin, 13 December 2007. 24) MISSELWITZ Hans, Berlin, 6 November 2007. 25) MODROW Hans, Berlin, 28 November 2007. 26) MÜLLER Hans-Peter, Berlin, 13 November 2007. 27) NOOKE Günther, Berlin, 27 November 2007. 28) PAU Petra, Berlin, 13 December 2007. 29) PLATZECK Matthias, Potsdam, 12 December 2007. 30) SABATHIL Gerhard, Berlin, 31 October 2007. 31) SARAZZIN Thilo, Berlin, 30 November 2007. 32) SCHABOWSKI Günther, Berlin, 3 December 2007. 33) SCHÄUBLE Wolfgang, Berlin, 19 December 2007. 34) SCHRÖDER Richard, Berlin, 4 December 2007. 35) SEGERT Dieter, Vienna, 18 June 2008. -

Mario Draghi: Laudatio for Theo Waigel

Mario Draghi: Laudatio for Theo Waigel Speech by Mr Mario Draghi, President of the European Central Bank, in honour of Dr Theodor Waigel, at SignsAwards, Munich, 17 June 2016. * * * James Freeman Clarke, a 19th century theologian, once observed that “a politician is a man who thinks of the next election, while a statesman thinks of the next generation”. This captures well why we are here to honour Theo Waigel today. Theo Waigel’s political career cannot just be defined by the elections he won, however many there were during his 30 years in the Bundestag. Nor can it be defined by his time as head of the CSU and as finance minister of Germany. It is defined by his legacy: a legacy that is still shaping Europe today. He became finance minister in 1989 at a turning-point in post-war European history – when the Iron Curtain that divided Europe was being lifted; when the walls and barbed wire that divided Germany were being removed. It was a time of great hopes and expectations. But it was also a time of some anxiety. It was clear that the successful reunification of Germany would be a tremendous undertaking. And many wondered what those changes would mean for the European Community – whether it would upset the balance of power that had prevailed between nations since the war. In that uncertain setting, Theo Waigel’s leadership was pivotal – both as a German and as a European. He was one of the strongest advocates of German reunification, and was instrumental in getting Germany’s federal and state governments to finance the reconstruction and modernisation of East Germany. -

What Does GERMANY Think About Europe?

WHat doEs GERMaNY tHiNk aboUt europE? Edited by Ulrike Guérot and Jacqueline Hénard aboUt ECFR The European Council on Foreign Relations (ECFR) is the first pan-European think-tank. Launched in October 2007, its objective is to conduct research and promote informed debate across Europe on the development of coherent, effective and values-based European foreign policy. ECFR has developed a strategy with three distinctive elements that define its activities: •a pan-European Council. ECFR has brought together a distinguished Council of over one hundred Members - politicians, decision makers, thinkers and business people from the EU’s member states and candidate countries - which meets once a year as a full body. Through geographical and thematic task forces, members provide ECFR staff with advice and feedback on policy ideas and help with ECFR’s activities within their own countries. The Council is chaired by Martti Ahtisaari, Joschka Fischer and Mabel van Oranje. • a physical presence in the main EU member states. ECFR, uniquely among European think-tanks, has offices in Berlin, London, Madrid, Paris, Rome and Sofia. In the future ECFR plans to open offices in Warsaw and Brussels. Our offices are platforms for research, debate, advocacy and communications. • a distinctive research and policy development process. ECFR has brought together a team of distinguished researchers and practitioners from all over Europe to advance its objectives through innovative projects with a pan-European focus. ECFR’s activities include primary research, publication of policy reports, private meetings and public debates, ‘friends of ECFR’ gatherings in EU capitals and outreach to strategic media outlets. -

DEFENDING the WOLF the Useful Contradiction of the Bundesbank Carlo Bastasin

DEFENDING THE WOLF The Useful Contradiction of the Bundesbank Carlo Bastasin SEP Policy Brief No. 1 - 2014 The Deutsche Bundesbank, the German central bank, is commonly regarded as the Euroarea's boogeyman. The pressure imparted by the German monetary authority, for instance, rendered the European Central Bank reluctant to follow the footprints of the Federal Reserve and of other central banks, and engage in non- standard monetary policy measures that might rapidly put an end to the crisis that has been plaguing the euro zone. At several stages, during the current crisis, the ECB has been forced to take actions and prevent severe economic and financial dislocations. Given the institutional vacuum at the area-wide level and the lack of political capacity of the other institutions, the European Central Bank had often to move across the borders of its traditional domain. This has given reason to a slew of criticisms repeatedly and loudly voiced by the Bundesbank. Being also the most vocal policy actor evoking the fiscal risks associated with effecting implicit cross-border transfers via the ECB's balance sheet, the Bundesbank has appeared to have a “non- monetary” hidden agenda or even a “national political” mission. In fact, the Bundesbank has regularly appealed to two fundamental principles of sound economic and monetary policy management that cannot be easily overlooked by anybody concerned that monetary policy may lose its ability to preserve price stability. Should monetary independence be eroded by the increasing tasks devolved to the central banks, wider economic and political consequences might then arise. The first principle is the need to avoid fiscal dominance, not allowing inflation to be determined by the level of fiscal debts; the second is the “principle of responsibility” that sees a contradiction if individual responsibility is blurred by the intervention of joint liability as in the case of a State running unsound fiscal policies and being automatically bailed out by the mutualization of its liabilities. -

Lu X Embu Rg

01 01 21 21 GESELLSCHAFTSANALYSE UND LINKE PRAXIS Lia Becker | Eric Blanc | Marcel Bois | Ulrike Eifler | Naika Foroutan | Alexander Harder | Paul Heinzel | Susanne Hennig-Wellsow | EMBURG Olaf Klenke | Elsa Koester | Kalle Kunkel | X Susanne Lang | Max Lill | Thomas Lißner | LU Rika Müller-Vahl | Sarah Nagel | Benjamin Opratko | Luigi Pantisano | Hanna Pleßow | Katrin Reimer-Gordinskaya | Thomas Sablowski | Daniel Schur | Jana Seppelt | Jeannine Sturm | Selana Tzschiesche | Jan van Aken | Moritz Warnke | Florian Weis | Janine Wissler | Lou Zucker Grün-schwarze Lovestory Corona und die Kultur der Ablehnung Aufbruch Ost Enteignen lernen Wahlkampf mit Methode Zetkin entdecken Antisemitismus im Alltag GEWINNEN LERNEN DIE ZEITSCHRIFT DER ROSA-LUXEMBURG-STIFTUNG ISSN 1869-0424 GEWINNEN LERNEN » Man muss ins Gelingen verliebt sein, nicht ins Scheitern. Ernst Bloch GEWINNEN LERNEN Wenn du anfängst, hast du einen Hammer. Und wenn du einen Hammer hast, sieht alles aus wie ein Nagel. Aber wenn man mehr Methoden kennenlernt, dann hat man plötzlich einen Schrauben - schlüssel, man hat eine Zange und man kann seinen Werkzeugen immer neue hinzufügen. »Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez EDITORIAL Manchmal verdichten sich gesellschaftliche Krisen- PRONOMEN BUSFAHRERIN mo mente in einem einzigen Wort. So war »Corona- Fridays for Future goes Arbeitskampf pan de mie« Wort des Jahres 2020, davor war es »Re spektrente«, und 2018 »Heißzeit«. Es sind die Gespräch mit Rika Müller-Vahl und Heraus forderungen unserer Gegenwart: das Ringen Paul Heinzel um eine solidarische Pandemiepolitik und gute Da- seinsvorsorge für alle, das Rennen gegen die Klima- katastrophe und der Kampf um einen Strukturwan- ALLIANZ DER del, der niemanden zurücklässt. Und das Wort des AUSGEGRENZTEN? Jahres 2021? Derzeit scheinen »Kanzlerkandidatin«, Was Ostdeutsche und »Schwarz-Grün« oder »Weiter-so« hoch im Kurs. -

Ostracized in the West, Elected in the East – the Successors of the SED

Volume 10. One Germany in Europe, 1989 – 2009 The Red Socks (June 24, 1994) The unexpected success of the successor party to the SED, the Party of Democratic Socialism (PDS), at the ballot box in East Germany put the established (Western) parties in a difficult situation: what response was called for, ostracism or integration? The essay analyzes the reasons behind the success of the PDS in the East and the changing party membership. The Party that Lights a Fire Ostracized in the West, voted for in the East – the successors to the SED are drawing surprising support. Discontent over reunification, GDR nostalgia, or a yearning for socialism – what makes the PDS attractive? Last Friday, around 12:30 pm, a familiar ritual began in the Bundestag. When representative Uwe-Jens Heuer of the PDS stepped to the lectern, the parliamentary group of the Union [CDU/CSU] transformed itself into a raging crowd. While Heuer spoke of his party’s SED past, heckling cries rained down on him: “nonsense,” “outrageous.” The PDS makes their competitors’ blood boil, more so than ever. Saxony-Anhalt votes for a new Landtag [state parliament] on Sunday, and the successor to the SED could get twenty percent of the vote. It did similarly well in the European elections in several East German states. In municipal elections, the PDS has often emerged as the strongest faction, for example, in Halle, Schwerin, Rostock, Neubrandenburg, and Hoyerswerda. A specter is haunting East Germany. Is socialism celebrating a comeback, this time in democratic guise? All of the Bonn party headquarters are in a tizzy. -

Interview with J.D. Bindenagel

Library of Congress Interview with J.D. Bindenagel The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project AMBASSADOR J.D. BINDENAGEL Interviewed by: Charles Stuart Kennedy Initial interview date: February 3, 1998 Copyright 2002 ADST Q: Today is February 3, 1998. The interview is with J.D. Bindenagel. This is being done on behalf of The Association for Diplomatic Studies. I am Charles Stuart Kennedy. J.D. and I are old friends. We are going to include your biographic sketch that you included at the beginning, which is really quite full and it will be very useful. I have a couple of questions to begin. While you were in high school, what was your interest in foreign affairs per se? I know you were talking politics with Mr. Frank Humphrey, Senator Hubert Humphrey's brother, at the Humphrey Drugstore in Huron, South Dakota, and all that, but how about foreign affairs? BINDENAGEL: I grew up in Huron, South Dakota and foreign affairs in South Dakota really focused on our home town politician Senator and Vice President Hubert H. Humphrey. Frank, Hubert Humphrey's brother, was our connection to Washington, DC, and the center of American politics. We followed Hubert's every move as Senator and Vice President; he of course was very active in foreign policy, and the issues that concerned South Dakota's farmers were important to us. Most of farmers' interests were in their wheat sales, and when we discussed what was happening with wheat you always had to talk about the Russians, who were buying South Dakota wheat. -

'Keynes Was an Extremely Political Person and We Should Be Too, Shouldn't

European Journal of Economics and Economic Policies: Intervention, Vol. 16 No. 1, 2019, pp. 1–7 ‘Keynes was an extremely political person and we should be too, shouldn’t we?’ Interview with Jan Priewe Jan Priewe is a retired Professor of Economics. He is a Senior Research Fellow of the Macroeconomic Policy Institute (IMK) and a Fellow and member of the coordination group of the Forum for Macroeconomics and Macroeconomic Policies (FMM). His research areas include macroeconomics, economic policies and development economics. He has authored, co-authored or co-edited 16 books and numerous articles. Jan received his PhD in economics at the University of Bremen, Germany, in 1982 and has been a professor since then, first at the University of Applied Sciences Darmstadt, Germany, and from 1993 onwards at the HTW Berlin, Germany, before he retired in 2014. Soon after the student movements of 1968 you started your academic life, right? I started in Konstanz, Germany, and after the first semester I moved to Marburg in 1970 where my friends from high school lived. There I faced an extremely conservative faculty and at that time it did not provide a good education. In a way I regret that I switched from the University of Konstanz to Marburg. However, there was a very active student life, including radical movements and especially Marxists of all kinds. I learned more from the post-1968 student activities and self-studies, including immense amounts of reading in social science and economics, than in the lecture rooms. We felt that something was wrong with standard economics textbooks but we had hardly any academic ‘masters’ in West Germany, so we had to teach ourselves. -

The Group of Twenty: a History

THE GROUP OF TWENTY : A H ISTORY The study of the G-20’s History is revealing. A new institution established less than 10 years ago has emerged as a central player in the global financial architecture and an effective contributor to global economic and financial stability. While some operational challenges persist, as is typical of any new institution, the lessons from the study of the contribution of the G-20 to global economic and financial stability are important. Because of the work of the G-20 we are already witnessing evidence of the benefits of shifting to a new model of multilateral engagement. Excerpt from the closing address of President Mbeki of South Africa to G-20 Finance Ministers and Central Bank Governors, 18 November 2007, Kleinmond, Western Cape. 2 Table of Contents Excerpt from a Speech by President Mbeki....................................................................2 Executive Summary...........................................................................................................5 The Group of Twenty: a History ......................................................................................7 Preface............................................................................................................................7 Background....................................................................................................................8 The G-22 .............................................................................................................12 The G-33 .............................................................................................................15 -

Xpenditures to More Socially Productive Uses

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 322 068 SO 030 105 AUTHOR Renner, Michael TITLE Swords into Plowshares: Converting to a Peace Economy. Worldwatch Paper 96. INSTITUTION Worldwatch Inst., Washington, D.C. REPORT NO ISBN-0-916468-97-6 PUB DATE Jun 90 NOTE 90p. AVAILABLE FROMWorldwatch Institute, 1776 Massachusetts Avenue, NW, Washington, DC 20036 ($4.00). PUB TYPE Reports - Descriptive (141) EDRS PRICE MF01 Plus Postage. PC Not Available from EDRS. DESCRIPTORS Disarmament; *Economics; Foreign Countries; Futures (of Society); Global Approach; *International Relations; *National Defense; *Peace; Social Change; World Problems IDENTIFIERS China; *Economic Conversion; Europe (East); USSR ABSTRACT Recent world developments have created an opportune time for nations to vigorously pursue a policy of converting the huge portion of their economies that traditionally have been devoted to military expenditures to more socially productive uses. This paper outlines a strategy for such a conversion, and discusses the issues that must be confronted in such a process. Specific aspects of conversion include: (1) misconceptions about lessening military spending; (2) building a conversion coalition; (3) the paths forged by China and the Soviet Union; (4) upheaval in Eastern Europe; and (5) grassroots initiatives in the West. It is concluded that the gathering pressLre for disarmament suggests that conversion will bea topic gaining importance during the 1990's. A number of statistical tables, chalts, and maps appear throughout this paper, and 127 endnotes are provided. (DB) -

Dezember 2017

★ ★ ★ Dezember ★ ★ 2017 ★ ★ ★ Vereinigung ehemaliger Mitglieder des Deutschen Bundestages und des Europäischen Parlaments e. V. Editorial Rita Pawelski Informationen ...Grüße aus dem Saarland Termine Personalien Titelthemen Mitgliederreise Saarland und Luxemburg Berichte / Erlebtes Europäische Assoziation Jahreshauptversammlung in Bonn Mein Leben danach Erlesenes Aktuelles Die Geschäftsführerin informiert Jubilare © Carmen Pägelow Editorial Informationen Willkommen in der Vereinigung der ehemaligen Abgeordneten, Termine © Thomas Rafalzyk liebe neue Ehemalige! 20.03.2018 Frühlingsempfang der DPG (voraussichtlich) Für mehr als 200 Abgeordnete 21.03.2018 Mitgliederversammlung der DPG (voraussichtlich) beginnt nun eine neue Lebens- 14./15.05.2018 Mitgliederveranstaltung mit zeit. Sie gehören dem Deutschen Empfang des Bundespräsidenten / Bundestag nicht mehr an. Je Jahreshauptversammlung mit Wahl / nach Alter starten sie entweder Studientag „Die Zukunft Europas“ in eine neue Phase der Berufs- 12.-20. Juni 2018 Mitgliederreise nach Rumänien tätigkeit oder sie bereiten sich auf ihren dritten Lebensabschnitt vor. Aber egal, was für sie für sich und ihre Zukunft geplant haben: die Zeit im Bundestag ist nun Vergangenheit. Personalien Ich weiß aus Erfahrung, dass der Übergang in die neue Zeit von vielen Erinnerungen – und manchmal auch von Wehmut – begleitet wird. Man hat doch aus Überzeugung im Deutschen Bundestag gearbeitet… und oft auch mit Herzblut. Man hatte sich an den Arbeitsrhythmus gewöhnt und daran, dass der Tag oft 14 bis 16 Arbeitsstunden hatte. Man schätzte die fleißigen Mitarbeiterinnen und Mitarbeiter im Büro, die Planungen über- © Deutscher Bundestag / Achim Melde nommen, Reisen gebucht, an Geburtstage erinnert, den Termin- kalender geführt, Sitzungen vorbereitet und Akten sortiert haben. Auf einmal ist man selbst dafür zuständig: welchen Zug muss ich nehmen, wann fährt der Bus, wer hat wann Geburtstag.