Stevenssamuel Fall2017.Pdf (3.667Mb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Military History Anniversaries 01 Thru 14 Feb

Military History Anniversaries 01 thru 14 Feb Events in History over the next 14 day period that had U.S. military involvement or impacted in some way on U.S military operations or American interests Feb 01 1781 – American Revolutionary War: Davidson College Namesake Killed at Cowan’s Ford » American Brigadier General William Lee Davidson dies in combat attempting to prevent General Charles Cornwallis’ army from crossing the Catawba River in Mecklenburg County, North Carolina. Davidson’s North Carolina militia, numbering between 600 and 800 men, set up camp on the far side of the river, hoping to thwart or at least slow Cornwallis’ crossing. The Patriots stayed back from the banks of the river in order to prevent Lieutenant Colonel Banastre Tartleton’s forces from fording the river at a different point and surprising the Patriots with a rear attack. At 1 a.m., Cornwallis began to move his troops toward the ford; by daybreak, they were crossing in a double-pronged formation–one prong for horses, the other for wagons. The noise of the rough crossing, during which the horses were forced to plunge in over their heads in the storm-swollen stream, woke the sleeping Patriot guard. The Patriots fired upon the Britons as they crossed and received heavy fire in return. Almost immediately upon his arrival at the river bank, General Davidson took a rifle ball to the heart and fell from his horse; his soaked corpse was found late that evening. Although Cornwallis’ troops took heavy casualties, the combat did little to slow their progress north toward Virginia. -

Colonial Contractions: the Making of the Modern Philippines, 1565–1946

Colonial Contractions: The Making of the Modern Philippines, 1565–1946 Colonial Contractions: The Making of the Modern Philippines, 1565–1946 Vicente L. Rafael Subject: Southeast Asia, Philippines, World/Global/Transnational Online Publication Date: Jun 2018 DOI: 10.1093/acrefore/9780190277727.013.268 Summary and Keywords The origins of the Philippine nation-state can be traced to the overlapping histories of three empires that swept onto its shores: the Spanish, the North American, and the Japanese. This history makes the Philippines a kind of imperial artifact. Like all nation- states, it is an ineluctable part of a global order governed by a set of shifting power rela tionships. Such shifts have included not just regime change but also social revolution. The modernity of the modern Philippines is precisely the effect of the contradictory dynamic of imperialism. The Spanish, the North American, and the Japanese colonial regimes, as well as their postcolonial heir, the Republic, have sought to establish power over social life, yet found themselves undermined and overcome by the new kinds of lives they had spawned. It is precisely this dialectical movement of empires that we find starkly illumi nated in the history of the Philippines. Keywords: Philippines, colonialism, empire, Spain, United States, Japan The origins of the modern Philippine nation-state can be traced to the overlapping histo ries of three empires: Spain, the United States, and Japan. This background makes the Philippines a kind of imperial artifact. Like all nation-states, it is an ineluctable part of a global order governed by a set of shifting power relationships. -

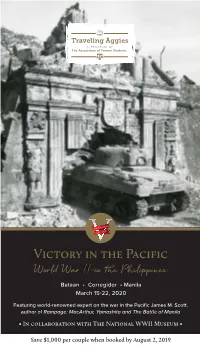

2020 Philippines A&M V2.Indd

y th Year of Victor Victory in the Pacific M A Y 19 4 World War II in the Philippines 5 Bataan • Corregidor • Manila March 15-22, 2020 Featuring world-renowned expert on the war in the Pacific James M. Scott, author of Rampage: MacArthur, Yamashita and The Battle of Manila • In collaboration with The National WWII Museum • Save $1,000 per couple when booked by August 2, 2019 1946 Corregidor Muster. Photo by James T. Danklefs ‘43 Howdy, Ags! On December 7, 1941, the Imperial Japanese Navy attacked the US Pacific Fleet The Traveling Aggies are pleased to partner with The National WWII Museum on at Pearl Harbor. Just a few hours later, the Philippines faced the same fury Victory in the Pacific: World War II in the Philippines. This fascinating journey will as the Japanese Army Air Force began bombing Clark Field, located north of begin in the lush province of Bataan, where tour participants will walk the first Manila. Five months later, the Japanese forced the Americans in the Philippines kilometer of the Death March and visit the remains of the prisoner of war camp at to surrender, but not before General MacArthur could slip away to Australia, Cabanatuan. On the island of Corregidor, 27 miles out in Manila Bay, guests will famously vowing, “I shall return.” see the blasted, skeletal remains of the mile-long barracks, theater, hospital, and officers’ quarters, as well as the monument built and dedicated by The Association After the fall of the Philippines, 70,000 captured American and Filipino soldiers near Malinta Tunnel in 2015, flying the Texas A&M flag and representing the were sent on the infamous “Bataan Death March,” a 65-mile forced march into sacrifice, bravery and Aggie Spirit of the men who Mustered there. -

World War Ii in the Philippines

WORLD WAR II IN THE PHILIPPINES The Legacy of Two Nations©2016 Copyright 2016 by C. Gaerlan, Bataan Legacy Historical Society. All Rights Reserved. World War II in the Philippines The Legacy of Two Nations©2016 By Bataan Legacy Historical Society Several hours after the bombing of Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, the Philippines, a colony of the United States from 1898 to 1946, was attacked by the Empire of Japan. During the next four years, thou- sands of Filipino and American soldiers died. The entire Philippine nation was ravaged and its capital Ma- nila, once called the Pearl of the Orient, became the second most devastated city during World War II after Warsaw, Poland. Approximately one million civilians perished. Despite so much sacrifice and devastation, on February 20, 1946, just five months after the war ended, the First Supplemental Surplus Appropriation Rescission Act was passed by U.S. Congress which deemed the service of the Filipino soldiers as inactive, making them ineligible for benefits under the G.I. Bill of Rights. To this day, these rights have not been fully -restored and a majority have died without seeing justice. But on July 14, 2016, this mostly forgotten part of U.S. history was brought back to life when the California State Board of Education approved the inclusion of World War II in the Philippines in the revised history curriculum framework for the state. This seminal part of WWII history is now included in the Grade 11 U.S. history (Chapter 16) curriculum framework. The approval is the culmination of many years of hard work from the Filipino community with the support of different organizations across the country. -

War Crimes in the Philippines During WWII Cecilia Gaerlan

War Crimes in the Philippines during WWII Cecilia Gaerlan When one talks about war crimes in the Pacific, the Rape of Nanking instantly comes to mind.Although Japan signed the 1929 Geneva Convention on the Treatment of Prisoners of War, it did not ratify it, partly due to the political turmoil going on in Japan during that time period.1 The massacre of prisoners-of-war and civilians took place all over countries occupied by the Imperial Japanese Army long before the outbreak of WWII using the same methodology of terror and bestiality. The war crimes during WWII in the Philippines described in this paper include those that occurred during the administration of General Masaharu Homma (December 22, 1941, to August 1942) and General Tomoyuki Yamashita (October 8, 1944, to September 3, 1945). Both commanders were executed in the Philippines in 1946. Origins of Methodology After the inauguration of the state of Manchukuo (Manchuria) on March 9, 1932, steps were made to counter the resistance by the Chinese Volunteer Armies that were active in areas around Mukden, Haisheng, and Yingkow.2 After fighting broke in Mukden on August 8, 1932, Imperial Japanese Army Vice Minister of War General Kumiaki Koiso (later convicted as a war criminal) was appointed Chief of Staff of the Kwantung Army (previously Chief of Military Affairs Bureau from January 8, 1930, to February 29, 1932).3 Shortly thereafter, General Koiso issued a directive on the treatment of Chinese troops as well as inhabitants of cities and towns in retaliation for actual or supposed aid rendered to Chinese troops.4 This directive came under the plan for the economic “Co-existence and co-prosperity” of Japan and Manchukuo.5 The two countries would form one economic bloc. -

Race and Ethnicity in the Era of the Philippine-American War, 1898-1914

Allegiance and Identity: Race and Ethnicity in the Era of the Philippine-American War, 1898-1914 by M. Carmella Cadusale Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the History Program YOUNGSTOWN STATE UNIVERSITY August, 2016 Allegiance and Identity: Race and Ethnicity in the Era of the Philippine-American War, 1898-1914 M. Carmella Cadusale I hereby release this thesis to the public. I understand that this thesis will be made available from the OhioLINK ETD Center and the Maag Library Circulation Desk for public access. I also authorize the University or other individuals to make copies of this thesis as needed for scholarly research. Signature: M. Carmella Cadusale, Student Date Approvals: Dr. L. Diane Barnes, Thesis Advisor Date Dr. David Simonelli, Committee Member Date Dr. Helene Sinnreich, Committee Member Date Dr. Salvatore A. Sanders, Dean of Graduate Studies Date ABSTRACT Filipino culture was founded through the amalgamation of many ethnic and cultural influences, such as centuries of Spanish colonization and the immigration of surrounding Asiatic groups as well as the long nineteenth century’s Race of Nations. However, the events of 1898 to 1914 brought a sense of national unity throughout the seven thousand islands that made the Philippine archipelago. The Philippine-American War followed by United States occupation, with the massive domestic support on the ideals of Manifest Destiny, introduced the notion of distinct racial ethnicities and cemented the birth of one national Philippine identity. The exploration on the Philippine American War and United States occupation resulted in distinguishing the three different analyses of identity each influenced by events from 1898 to 1914: 1) The identity of Filipinos through the eyes of U.S., an orientalist study of the “us” versus “them” heavily influenced by U.S. -

The Thirteenth Minnesota and the Mock Battle of Manila by Kyle Ward on the Evening of February 15, 1898, There Was an Explosion Within the U.S.S

winter16allies_Layout 1 1/20/2016 4:20 PM Page 1 Winter, 2016 Vol. XXIV, No. 1 The Thirteenth Minnesota and the mock battle of Manila By Kyle Ward On the evening of February 15, 1898, there was an explosion within the U.S.S. Maine, which was stationed in Havana Harbor outside the Cuban capital city. Had it happened anywhere else in the world, this event proba- bly would not have had such huge implications, but be- cause it happened when and where it did, it had a major impact on the course of American history. And although it happened 2,000 miles from Minnesota, it had a huge impact on Minnesotans as well. The sinking of the USS Maine, which killed 266 crew members, was like the last piece of a vast, complex puzzle that, once pressed into place, completed the pic- ture and caused the United States and the nation of Spain to declare war against one another. Their diplomatic hos- tilities had been going on for a number of years, primarily due to Cuban insurgents trying to break away from their long-time colonial Spanish masters. Spain, for its part, The battle flags of the Thirteenth Minnesota, flown at camp in San Francisco, California. (All photos for this story are from the was trying to hold on to the last remnants of its once collection of the Minnesota Historical Society.) great empire in the Western Hemisphere. Many Americans saw a free Cuba as a potential region for investment and growth, while others sided with April 23, 1898, President William McKinley, a Civil War the Cubans because it reminded them of their own na- veteran, asked for 125,000 volunteers from the states to tion’s story of a small rebel army trying to gain independ- come forward and serve their nation. -

Philippine History and Government

Remembering our Past 1521 – 1946 By: Jommel P. Tactaquin Head, Research and Documentation Section Veterans Memorial and Historical Division Philippine Veterans Affairs Office The Philippine Historic Past The Philippines, because of its geographical location, became embroiled in what historians refer to as a search for new lands to expand European empires – thinly disguised as the search for exotic spices. In the early 1400’s, Portugese explorers discovered the abundance of many different resources in these “new lands” heretofore unknown to early European geographers and explorers. The Portugese are quickly followed by the Dutch, Spaniards, and the British, looking to establish colonies in the East Indies. The Philippines was discovered in 1521 by Portugese explorer Ferdinand Magellan and colonized by Spain from 1565 to 1898. Following the Spanish – American War, it became a territory of the United States. On July 4, 1946, the United States formally recognized Philippine independence which was declared by Filipino revolutionaries from Spain. The Philippine Historic Past Although not the first to set foot on Philippine soil, the first well document arrival of Europeans in the archipelago was the Spanish expedition led by Portuguese Ferdinand Magellan, which first sighted the mountains of Samara. At Masao, Butuan, (now in Augustan del Norte), he solemnly planted a cross on the summit of a hill overlooking the sea and claimed possession of the islands he had seen for Spain. Magellan befriended Raja Humabon, the chieftain of Sugbu (present day Cebu), and converted him to Catholicism. After getting involved in tribal rivalries, Magellan, with 48 of his men and 1,000 native warriors, invaded Mactan Island. -

Redalyc.Encuentros Y Desencuentros Político-Jurídicos. El Gobierno

Relaciones. Estudios de historia y sociedad ISSN: 0185-3929 [email protected] El Colegio de Michoacán, A.C México Ramírez Bonilla, Juan José Encuentros y desencuentros político-jurídicos. El gobierno mexicano ante la Asociación de Naciones del Sureste de Asia Relaciones. Estudios de historia y sociedad, vol. XXXIII, núm. 131, 2012, pp. 135-180 El Colegio de Michoacán, A.C Zamora, México Disponible en: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=13725131005 Cómo citar el artículo Número completo Sistema de Información Científica Más información del artículo Red de Revistas Científicas de América Latina, el Caribe, España y Portugal Página de la revista en redalyc.org Proyecto académico sin fines de lucro, desarrollado bajo la iniciativa de acceso abierto Encuentros y desencuentros político- jurídicos. El gobierno mexicano ante la Asociación de Naciones del Sureste de Asia Juan José Ramírez Bonilla* EL COLEGIO DE MÉXICO Las administraciones 1994-2000, 2000-2006 y 2006-2012 del gobierno mexicano han colocado en un lugar privilegiado de la agenda de política exte- rior la formalización de la relación bilateral con la Asociación de Naciones del Sureste de Asia (ansea). Las contrapartes de la Asociación, no obstante, opta- ron por archivar las solicitudes del gobierno mexicano en la medida en que consideran a México como un país importante en América del Norte, pero con poca relevancia en la región del Pacífico; además, la práctica de una polí- tica exterior basada en la defensa de la democracia y de los derechos humanos por parte de la administración de Vicente Fox fue considerada riesgosa por gobiernos que toman en cuenta los principios de la Carta de las Naciones Unidas como la garantía de la convivencia internacional armónica. -

Uimersity Mcrofihns International

Uimersity Mcrofihns International 1.0 |:B litt 131 2.2 l.l A 1.25 1.4 1.6 MICROCOPY RESOLUTION TEST CHART NATIONAL BUREAU OF STANDARDS STANDARD REFERENCE MATERIAL 1010a (ANSI and ISO TEST CHART No. 2) University Microfilms Inc. 300 N. Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, MI 48106 INFORMATION TO USERS This reproduction was made from a copy of a manuscript sent to us for publication and microfilming. While the most advanced technology has been used to pho tograph and reproduce this manuscript, the quality of the reproduction Is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. Pages In any manuscript may have Indistinct print. In all cases the best available copy has been filmed. The following explanation of techniques Is provided to help clarify notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1. Manuscripts may not always be complete. When It Is not possible to obtain missing pages, a note appears to Indicate this. 2. When copyrighted materials are removed from the manuscript, a note ap pears to Indicate this. 3. Oversize materials (maps, drawings, and charts) are photographed by sec tioning the original, beginning at the upper left hand comer and continu ing from left to right In equal sections with small overlaps. Each oversize page Is also filmed as one exposure and Is available, for an additional charge, as a standard 35mm slide or In black and white paper format. * 4. Most photographs reproduce acceptably on positive microfilm or micro fiche but lack clarify on xerographic copies made from the microfilm. For an additional charge, all photographs are available In black and white standard 35mm slide format.* *For more information about black and white slides or enlarged paper reproductions, please contact the Dissertations Customer Services Department. -

A Splendid Little War"

A S P L E N D I D L I T T L E W A R A CHRONOLOGY OF HEROISM IN THE SPANISH-AMERICAN WAR By C. Douglas Sterner Table of Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................. 1 A War Looking for an Excuse to Happen ................................................................... 3 Manifest Destiny & Yellow Journalism ................................................................. 5 Prelude to War ............................................................................................................. 8 Remember the Maine .................................................................................................. 11 Trouble in Paradise ...................................................................................................... 17 The Battle of Manila Bay ............................................................................................ 21 Cutting the Cables at Cienfuegos ................................................................................ 25 Cable Cutters Who Received Medals of Honor ..................................................... 29 The Sinking of the Merrimac ...................................................................................... 33 War in The Jungle ....................................................................................................... 43 Guantanamo Bay ................................................................................................... 44 The Cuzco Well ..................................................................................................... -

Cartoon Commentary & “The White Man's Burden” (1898–1902)

Volume 13 | Issue 27 | Number 1 | Article ID 4339 | Jul 06, 2015 The Asia-Pacific Journal | Japan Focus Civilization & Barbarism: Cartoon Commentary & “The White Man’s Burden” (1898–1902) Ellen Sebring with meticulous attention to detail. Most viewers will probably agree that there is nothing really comparable in the contemporary world of political cartooning to the drafting skill and flamboyance of these single-panel graphics, which appeared in such popular periodicals as Puck and Judge. This early outburst of what we refer to today as clash-of-civilizations thinking did not go unchallenged, however. The turn of the century also witnessed emergence of articulate anti- imperialist voices worldwide—and this movement had its own powerful wing of incisive graphic artists. In often searing Rudyard Kipling’s famous poem “The White graphics, they challenged the complacent Man’s Burden” was published in 1899, during a propagandists for Western expansion by high tide of British and American rhetoric addressing (and illustrating) a devastating about bringing the blessings of “civilization and question about the savage wars of peace. Who, progress” to barbaric non-Western, non- they asked, was the real barbarian? Christian, non-white peoples. In Kipling’s often- quoted phrase, this noble mission required INTRODUCTION willingness to engage in “savage wars of peace.” The march of “civilization” against “barbarism” is a late-19th-century construct that cast Three savage turn-of-the-century conflicts imperialist wars as moral crusades. Driven by defined the milieu in which such rhetoric competition with each other and economic flourished: the Anglo-Boer War of 1899–1902 in pressures at home, the world’s major powers South Africa; the U.S.