Bicton College of Agriculture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bicton College

•Department •Department for Education for Business Innovation & Skills Jeremy Yabsley Minister for Skills and Chair of Governors Equalities Bicton College 1 Victoria Street London East Budleigh SW1H OET Budleigh Salterton T +44 (0) 20 7215.5000 E [email protected] Devon www.gov.uk/bis EX97BY www.education.gov.uk 30 October 2014 A-.__ rl 1~L ~~ . I am writing to confirm the tcome of the FE Commissioner Structure and Prospect · Appraisal of your Colle , and to set out the actions we now expect the College to take to ensure the Appraisal outcomes, and the FE Commissioner's earlier assessment, are fully implemented. I am very grateful for the support that the FE Commissioner has received from yourself and the College during the Appraisal, and the steps you have taken to date to respond to the recommendations in my predecessor's letter of 22 April 2014. As you are aware, in light of the notification by the Skills Funding Agency that the College's financial health is inadequate, the FE Commissioner reviewed the position of your College between 17 and 28 March 2014. The FE Commissioner acknowledged the capacity and capability of the governance and leadership to deliver financial recovery in the short term, but concluded that the College could not continue to operate on its own. The FE Commissioner was asked to lead a Structure and Prospects Appraisal to determine the way forward for land-based provision in the area. This Appraisal was completed in September 2014. I have now received the FE Commissioner's Appraisal report - a copy of which is attached. -

Download a Prospectus

CAREERS & COURSES GUIDE 2021 FOR SCHOOL LEAVERS Welcome to #thecareercollege WELCOME CHOOSE Welcome to The Cornwall College Group and thank you for considering the incredible opportunities that Over 1,200 acres for Award-winning await you at one of our fantastic campuses. I’m sure as you explore the prospectus, like most people, you THE CAREER COLLEGE will quickly realise why we are also known as ‘The Career College’. land-based training students and staff This careers and courses guide has been designed for school leavers and focuses on career Our mission is to provide exceptional education and training for every learner to improve their career pathways. Our course information provides details of full-time study options (career edge) prospects. We know that your future success needs more than just a certificate. It requires a meaningful and engaging course that has been developed alongside employers. Our courses ensure you have all the skills or apprenticeships (career now). It showcases a wide choice of careers, available through and experience required for you to secure that rewarding career or progress onto higher qualifications. our broad-based curriculum, from agriculture to zoology and everything in between. The great news is there has never been a better time to study with us. We have invested heavily in our £30 million investment in Industry partners to ensure campuses, our teaching and our student experiences. A passion for learning, training and rewarding careers equipment and connectivity courses stay relevant can be felt on every campus in our Group. Our incredible story is receiving positive local and national attention and we would love for you to be part of this. -

Year 13 Tutor Evening

About this evening UCAS questions – Unifrog workshop – Meet your child’s Tutor Mrs Terry students Haring Block Sixth Form Learning Sixth Form Learning Resource Centre Resource Centre Supporting wellbeing – Student Services Ms Daniel and Mrs Street Haring Block, Ground Haring Block, Ground Floor classroom Floor classroom (Re-)introducing the team Tom Kershaw Kim Daniel Academic Personal Performance Heather Lilley Development Sharon Terry Sarah Street Trina Nichols Leader Associate Deputy and Welfare Pastoral Leader – Pastoral Leader – Administrator Principal KS5 Leader Futures and Careers Welfare Year 13 Key Dates 13 August Results Day 19 November Student Finance Talk 26 June Prom 27 November 5 July Careers Fair 6 November 22 May Clearing Tutor Evening 15 January Leavers’ Assembly opens UCAS Deadline Nov Dec Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug 13-17 January Mock exams 12 February Late May – late June Parents’ Evening Main Examination Period 29/30 January, TBC National Apprenticeships Show (Westpoint, Exeter) Routines: pastoral system Students must still attend Tutor Block starting 8.50am. The main priority for the Sixth Form pastoral system is to help all students achieve their potential. Attending Tutor Block means that: • students are on-time and prepared for their first lesson; • students can use study blocks effectively, as they are in a work environment; • we can check up on students’ wellbeing and mental health; • we can pass on key messages related to opportunities, etc.; • we can help to develop the mindset and character traits of successful learners; • we can best support students onto their future pathways; and • we can deliver other important aspects of PSHE. -

Royal Air Force Visits to Schools

Location Location Name Description Date Location Address/Venue Town/City Postcode NE1 - AFCO Newcas Ferryhill Business and tle Ferryhill Business and Enterprise College Science of our lives. Organised by DEBP 14/07/2016 (RAF) Enterprise College Durham NE1 - AFCO Newcas Dene Community tle School Presentations to Year 10 26/04/2016 (RAF) Dene Community School Peterlee NE1 - AFCO Newcas tle St Benet Biscop School ‘Futures Evening’ aimed at Year 11 and Sixth Form 04/07/2016 (RAF) St Benet Biscop School Bedlington LS1 - Area Hemsworth Arts and Office Community Academy Careers Fair 30/06/2016 Leeds Hemsworth Academy Pontefract LS1 - Area Office Gateways School Activity Day - PDT 17/06/2016 Leeds Gateways School Leeds LS1 - Area Grammar School at Office The Grammar School at Leeds PDT with CCF 09/05/2016 Leeds Leeds Leeds LS1 - Area Queen Ethelburgas Office College Careers Fair 18/04/2016 Leeds Queen Ethelburgas College York NE1 - AFCO Newcas City of Sunderland tle Sunderland College Bede College Careers Fair 20/04/2016 (RAF) Campus Sunderland LS1 - Area Office King James's School PDT 17/06/2016 Leeds King James's School Knareborough LS1 - Area Wickersley School And Office Sports College Careers Fair 27/04/2016 Leeds Wickersley School Rotherham LS1 - Area Office York High School Speed dating events for Year 10 organised by NYBEP 21/07/2016 Leeds York High School York LS1 - Area Caedmon College Office Whitby 4 x Presentation and possible PDT 22/04/2016 Leeds Caedmon College Whitby Whitby LS1 - Area Ermysted's Grammar Office School 2 x Operation -

Weekly Parent Bulletin Week Commencing 5Th November, 2018 - Week 1

THE PARK COMMUNITY SCHOOL Weekly Parent Bulletin Week Commencing 5th November, 2018 - Week 1 SCHOOL CALENDAR FOOD AT PARK Date Event The Autumn term menus have Tues 6th Nov 7x PTE Church Visit been added to our website on our Year 9 Football v Pilton (Home) 4-5pm website food page Main meals are £1.80, and 2 Weds 7th Nov Y10/11 monitoring home (emailed) courses are £2.30. Breakfast club Thurs 8th Nov 7x PTE Church Visit opens 8.15am-8.45am. Year 7/10 Football Semi Cup Final (Home) 4-5pm Fri 9th Nov Childrens’ Remembrance Service in Rock Park LETTERS ISSUED THIS WEEK - BY STUDENT POST Sat 10th Nov English School’s Cross Country Cup @ Downside School Somerset Check below to see if your child should have a letter. HEADTEACHER UPDATE (Copy on website or click link) School Hall Update Year Topic You may be aware that our School Hall suffered at 9 Parents Evening letter and the hands of Storm Callum just before the half term form break. Thanks to the work of the site team and in 10 Year 10 - Teenage Cancer particular Mr Elliott, our facilities manager, we have Trust Letter (emailed) already undertaken some major work on the School Hall. Sadly, the Hall will remain out of action for the possible mental health issues. foreseeable future whilst we carry out repairs and lay a new floor. Unfortunately this will cause some disruption for the school and students, however, this is unavoidable. For the remainder of this term, any parents evenings will be held in the Canteen and classrooms. -

Responses to the Consultation on the Proposed Post-16 Transport Policy for 2017-18

Responses to the Consultation on the Proposed Post-16 Transport Policy for 2017-18 Concerns Anthony Tschuk I am a social worker with the Community Health and Social Care team based in Newton Abbot. I am Specialised Social Worker (ASYE currently supporting Mr SG. I have been advised that there has been a consultation with regard to provision for Disability focussed) school transport, whereby DCC will not offer any assistance with travel unless there is no other means students with for the young person to access education. SEND S has previously been assessed by DCC Behaviour Support worker as unable to access any other means of transport to get him to college. I feel that this is the case at this moment in time. I am working with S in conjunction with the Community Enablement Team to reassess him and support him to use public transport. However, he may not be ready to use an alternative before returning to college in September Dr Phil Le Grice Thank you for the opportunity to comment on the consultation on education transport policy for 2016/17 Impact on choices Principal Bicton College and 2017/18. for students and Director of Rural Access to Economy The Cornwall In overview, anything that makes the decision to embark upon further study cumbersome or financially specialist courses College Group challenging will affect participation at our college. In particular, at a time when the raising of the Signposting to participation age is having the unintended consequence of leading families to the belief that learners advice and might need to stay on in their current schools with 6th forms, any bureaucracy that tends to reinforce support that misconception, or emphasise alternatives is unhelpful. -

The UPC Story Second Edition

The UPC Story Second Edition The continuing development of University of Plymouth Colleges Revised by Mark Stone and Adrian Lee University of Plymouth January 2010 UPC Story Cover v3.indd 1 22/12/2009 10:17:14 UPC Story The development of the University of Plymouth Colleges Faculty; a national and internationally recognised network delivering high quality HE in FE opportunities and success for learners and the South West region. An overview The recognisable start of the University of Plymouth Colleges story began in the mid 1970s. During the late 1970s and early 1980s relationships started to develop between Plymouth Polytechnic and a small number of Further Education Colleges [FECs] in Devon, Cornwall and Somerset. There was a trend for colleges to further develop and extend day-release programmes and at the same time to move into general vocational education, including: training schemes for the unemployed, vocational preparation programmes and academic education in the form of ‘A’ levels. Even with these modest developments, by the early 1980s, nationally around 20% of HE students were in FECs. The mid-70s also saw the first Access programmes, originally in the inner London area but they quickly grew to cover the country and involved links between Polytechnics and local FECs. This was accompanied by an increase in demand, particularly from mature students, women returners and people in employment for locally-available higher education [HE] opportunities. This was a significant development as further partnerships and franchises of higher education courses developed from such agreements. Since this time, UPC has grown from its modest start in 1989 when the newly named Polytechnic South West recognised that the opportunities for higher level study in the region’s scattered rural environment were limited. -

Exeter Careers Fair at St James School Which Is Open to All Students, Parents and Carers in the Exeter and Surrounding Areas

PAGE 1 EXETER CAREERS FAIRWEDNESDAY 26th APRIL 2017 HOSTED AT St James School Summer Lane, Exeter INTERVIEW TECHNIQUE UNIVERSITY INTERNSHIPS FUTURE INSPIRATION PROFESSIONAL PUBLIC SERVICES ADVISE CONTACTS WORK APPRENTICESHIPS OPPORTUNITIES CV WRITING For Students from the Exeter Area Looking to Find their Career Pathway PAGE 2 PAGE 3 INTRODUCTION We are delighted to welcome you to Exeter Careers Fair at St James School which is open to all students, parents and carers in the Exeter and surrounding areas. The aim of the event is to give students the opportunity to gather information, explore options on their doorstep and beyond, to attain knowledge and help shape decision making for their future subject choices. The event will be an opportunity for students, parents and carers to talk to a wide range of organisations about career pathways open to them, including the qualifications and skills “The best required. We very much hope that students will feel inspired and excited about the event and will leave with a greater awareness of the world of work. Forging links with local businesses is an way to predict important asset to widening the horizons of career opportunities and making students think about careers they didn’t even know existed! your future is We very much look forward to seeing you at the event. TO CREATE it.” CONTENTS Abraham Lincoln Page 4 - 5 Apprenticeships Page 6 - 7 Further Education Page 8 - 9 Higher Education Page 10 - 14 Companies Page 15 Armed Forces and Emergency Services Page 15 Local Government and Health Service Page 17 - 19 Workshops All information and details correct at time of printing. -

Somerset Schools Minehead Watchet Kilve Shepton Mallet

Somerset County Schools Somerset Mendip Hills Burnham-on-Sea Frome Porlock Wells Somerset Schools Minehead Watchet Kilve Shepton Mallet West Somerset College Glastonbury Exford Bridgwater & Taunton College (Cannington) Bridgwater Quantock Bruton Chilton Trinity Hills Street Bridgwater & Taunton College (Bridgwater) North Petherton Exmoor Bridgwater College Academy National Park Somerton Haygrove School Wiveliscombe Robe� Blake Science College Taunton The Castle School Bridgwater & Taunton College (Taunton) Wellington Richard Huish College Bishop Fox’s School Chard Yeovil Heathfi eld Community School The Taunton Academy Holyrood Academy Strode College The Blue School Whitstone School Buckler’s Mead Academy Preston School Yeovil College nextstepssw.ac.uk [email protected] Plymouth College of Art St Boniface’s Catholic College Lipson Co-operative Academy Devon County Schools Plymstock School PCA Pre-Degree Campus Millbay Academy Tor Bridge High Plymouth Marjon University Devon All Saints Church Of England Academy Sir John Hunt Community Sports College Plympton Academy Hele’s School Plymouth Studio School Exeter College Isca Academy St Lukes’s Science and Sports College St Peter’s Church of England Aided School West Exe School Exeter College University of Exeter Clyst Vale Community College Exmouth Community College Honiton Community College Queen Elizabeth School St James School City College Plymouth Eggbuckland Community College City College Plymouth Stoke Damerel Community College Petroc Bideford College Cullompton Community College -

Plymstock School We Recommend That All Students Have a Preferred Option and a Realistic Backup Plan

Dear Year 11 Student and Year 11 Parent/Carer, As Year 11 is well under way we would like to provide you with some Careers Guidance. Firstly, you need to remember that you have to remain in education or training until you are 18. Your options are: Stay in full time education at any sixth form provider Enrol in a course at a college or training provider Secure a full time apprenticeship or complete a pre-apprenticeship training scheme You will have a Careers Meeting with our Careers Advisor and follow up sessions as required. Please take time to read this booklet and consider your options. At Plymstock School we recommend that all students have a preferred option and a realistic backup plan. Remember the more you do towards your career preparation, the happier you will be with your choice. Guide to Next Steps What happens in Year 11? A-levels: Everything you need to know Find out if A-levels are right for you A-LEVELS AT A GLANCE What is it? An A-level is a qualification offered across a range of subjects to school-leavers (usually aged 16 to 18), graded A*-E. A-levels are studied across two years. What are ‘facilitating subjects’? Facilitating subjects are subjects that open you up to a wider range of degree courses. They are: Biology, Chemistry, Physics History Maths (and further Maths) English Literature Modern and classical languages Geography What is an Apprenticeship? It’s a real job, with real training, meaning you can earn while you learn and gain a nationally recognised qualification. -

South West England

South West England Extrait du AS Lagny Rugby http://www.aslagnyrugby.net/South-West-England.html South West England - Liens - Date de mise en ligne : dimanche 7 décembre 2014 Copyright © AS Lagny Rugby - Tous droits réservés Copyright © AS Lagny Rugby Page 1/34 South West England Cette page regroupe les clubs du Sud-Ouest de l'Angleterre (South West England) représentés par leurs couleurs (logo ou écusson si nous l'avons trouvé) et le lien vers leur site internet ou le blog qui leur est consacré. Ils sont regroupés selon les 6 comtés cérémoniaux (ceremonial county) plus Bristol : Somerset, Bristol, Gloucestershire, Wiltshire, Dorset, Devon et Cornouailles (Cornwall). Sont également listés les clubs des îles anglo-normandes Jersey et Guernesey. N'hésitez pas à nous contacter si vous constatez une erreur, un oubli, où si vous possédez le logo manquant d'un club, son adresse internet. Somerset (Bath)Bath Combination RFC [Bath Combination Rugby Football Club] (Bath)Bath Rugby Copyright © AS Lagny Rugby Page 2/34 South West England [Bath Rugby] (Bath)Bath Saracens RFC [Bath Saracens Rugby Football Club] (Bath)Old Sulians RFC [Old Sulians Rugby Football Club] (Bath (Odd Down))Old Culverhaysians RFC [Old Culverhaysians Rugby Football Club] (Bathampton)Bath Old Edwardians RFC [Bath Old Edwardians Rugby Football Club] (Batheaston)Avon RFC [Avon Rugby Football Club] (Bathford)Avonvale RFC [Avonvale Rugby Football Club] (Bridgwater)Blake Bears RFC Pas de logoà notre connaissance. (Bridgwater)Bridgwater & Albion RFC [Bridgwater & Albion Rugby Football Club] Copyright © AS Lagny Rugby Page 3/34 South West England (Bridgwater)Morganians RFC [Morganians Rugby Football Club] (Burnham-on-Sea )Burnham on Sea RFC [Burnham on Sea Rugby Football Club] (Butleigh)Butleigh Amateur RFC Pas de logoà notre connaissance. -

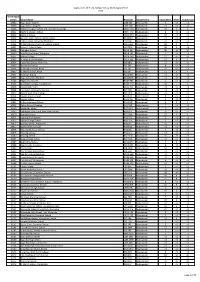

Applications, Offers & Acceptances by UCAS Apply Centre

Applications, Offers & Acceptances by UCAS Apply Centre 2018 UCAS Apply Centre School Name Postcode School Sector Applications Offers Acceptances 10002 Ysgol David Hughes LL59 5SS Maintained 6 <3 <3 10006 Ysgol Gyfun Llangefni LL77 7NG Maintained <3 <3 <3 10008 Redborne Upper School and Community College MK45 2NU Maintained 10 3 3 10011 Bedford Modern School MK41 7NT Independent 8 <3 <3 10012 Bedford School MK40 2TU Independent 17 <3 <3 10018 Stratton Upper School, Bedfordshire SG18 8JB Maintained <3 <3 <3 10024 Cedars Upper School, Bedfordshire LU7 2AE Maintained <3 <3 <3 10026 St Marylebone Church of England School W1U 5BA Maintained 10 3 3 10027 Luton VI Form College LU2 7EW Maintained 29 3 <3 10029 Abingdon School OX14 1DE Independent 30 10 10 10030 John Mason School, Abingdon OX14 1JB Maintained 5 <3 <3 10032 Radley College OX14 2HR Independent 11 <3 <3 10033 St Helen & St Katharine OX14 1BE Independent 15 4 4 10034 Heathfield School, Berkshire SL5 8BQ Independent <3 <3 <3 10036 The Marist School SL5 7PS Independent 4 <3 <3 10038 St Georges School, Ascot SL5 7DZ Independent <3 <3 <3 10039 St Marys School, Ascot SL5 9JF Independent 11 5 4 10041 Ranelagh School RG12 9DA Maintained <3 <3 <3 10043 Ysgol Gyfun Bro Myrddin SA32 8DN Maintained <3 <3 <3 10044 Edgbarrow School RG45 7HZ Maintained 6 <3 <3 10045 Wellington College, Crowthorne RG45 7PU Independent 30 7 5 10046 Didcot Sixth Form OX11 7AJ Maintained <3 <3 <3 10048 Faringdon Community College SN7 7LB Maintained <3 <3 <3 10053 Oxford Sixth Form College OX1 4HT Independent <3 <3