Media Framing and the Cancellation of NASA's Space Shuttle Program Nicholas J

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nasa Langley Research Center 2012

National Aeronautics and Space Administration NASA LANGLEY RESEARCH CENTER 2012 www.nasa.gov An Orion crew capsule test article moments before it is dropped into a An Atlantis flag flew outside Langley’s water basin at Langley to simulate an ocean splashdown. headquarters building during NASA’s final space shuttle mission in July. Launching a New Era of Exploration Welcome to Langley NASA Langley had a banner year in 2012 as we helped propel the nation toward a new age of air and space. From delivering on missions to creating new technologies and knowledge for space, aviation and science, Langley continued the rich tradition of innovation begun 95 years ago. Langley is providing leading-edge research and game-changing technology innovations for human space exploration. We are testing prototype articles of the Orion crew vehicle to optimize designs and improve landing systems for increased crew survivability. Langley has had a role in private-industry space exploration through agreements with SpaceX, Sierra Nevada Corp. and Boeing to provide engineering expertise, conduct testing and support research. Aerospace and Science With the rest of the world, we held our breath as the Curiosity rover landed on Mars – with Langley’s help. The Langley team performed millions of simulations of the entry, descent and landing phase of the Mars Science Laboratory mission to enable a perfect landing, Langley Center Director Lesa Roe and Mark Sirangelo, corporate and for the first time made temperature and pressure vice president and head of Sierra Nevada Space Systems, with measurements as the spacecraft descended, providing the Dream Chaser Space System model. -

GAO-07-595T NASA: Issues Surrounding the Transition from The

United States Government Accountability Office Testimony before the Subcommittee on GAO Space, Aeronautics, and Related Sciences, Committee on Commerce, Science and Transportation, U.S. Senate For Release on Delivery Expected at 2:30 p.m. EDT Wednesday, March 28, 2007 NASA Issues Surrounding the Transition from the Space Shuttle to the Next Generation of Human Space Flight Systems Statement of Allen Li, Director Acquisition and Sourcing Management GAO-07-595T March 28, 2007 NASA Accountability Integrity Reliability Highlights Issues Surrounding the Transition from Highlights of GAO-07-595T, a testimony the Space Shuttle to the Next Generation before the Subcommittee on Space, Aeronautics, and Related Sciences, of Human Space Flight Systems Committee on Commerce, Science and Transportation, U. S. Senate Why GAO Did This Study What GAO Found On January 14, 2004, the President NASA is in the midst of a transition effort of a magnitude not seen since the announced a new Vision for space end of the Apollo program and the start of the Space Shuttle Program more exploration that directs the than 3 decades ago. This transition will include a massive transfer of people, National Aeronautics and Space hardware, and infrastructure. Based on ongoing and work completed to- Administration (NASA) to focus its date, we have identified a number of issues that pose unique challenges to efforts on returning humans to the moon by 2020 in preparation for NASA as it transitions from the shuttle to the next generation of human future, more ambitions missions. space flight systems while at the same time seeking to minimize the time the United States will be without its own means to put humans in space. -

Corporate Initiative for Space Tourism

UNIVERSITY OF LJUBLJANA FACULTY OF ECONOMICS MASTER’S THESIS “OUT OF THIS WORLD” BUSINESS: CORPORATE INITIATIVE FOR SPACE TOURISM Ljubljana, March 2014 JAN KRIŠTOF RAMOVŠ AUTHORSHIP STATEMENT The undersigned Jan K. Ramovš, a student at the University of Ljubljana, Faculty of Economics, (hereafter: FELU), declare that I am the author of the master’s thesis entitled “Out Of This World” Business: Corporate Initiative for Space Tourism, written under supervision of Prof. Dr. Metka Tekavčič. In accordance with the Copyright and Related Rights Act (Official Gazette of the Republic of Slovenia, Nr. 21/1995 with changes and amendments) I allow the text of my master’s thesis to be published on the FELU website. I further declare the text of my master’s thesis to be based on the results of my own research; the text of my master’s thesis to be language-edited and technically in adherence with the FELU’s Technical Guidelines for Written Works which means that I o cited and / or quoted works and opinions of other authors in my master’s thesis in accordance with the FELU’s Technical Guidelines for Written Works and o obtained (and referred to in my master’s thesis) all the necessary permits to use the works of other authors which are entirely (in written or graphical form) used in my text; to be aware of the fact that plagiarism (in written or graphical form) is a criminal offence and can be prosecuted in accordance with the Criminal Code (Official Gazette of the Republic of Slovenia, Nr. 55/2008 with changes and amendments); to be aware of the consequences a proven plagiarism charge based on the submitted master’s thesis could have for my status at the FELU in accordance with the relevant FELU Rules on Master’s Thesis. -

The Role and Training of NASA Astronauts In

Co-chairs: Joe Rothenberg, Fred Gregory Briefing: October 18-19, 2011 Statement of Task An ad hoc committee will conduct a study and prepare a report on the activities of NASA’s human spaceflight crew office. In writing its report the committee will address the following questions: • How should the role and size of the activities managed by the Johnson Space Center Flight Crew Operations Directorate change after space shuttle retirement and completion of the assembly of the International Space Station (ISS)? • What are the requirements of crew-related ground-based facilities after the space shuttle program ends? • Is the fleet of aircraft used for the training the Astronaut Corps a cost-effective means of preparing astronauts to meet the requirements of NASA’s human spaceflight program? Are there more cost-effective means of meeting these training requirements? The NRC was not asked to consider whether or not the United States should continue human spaceflight, or whether there were better alternatives to achieving the nation’s goals without launching humans into space. Rather, the NRC’s charge was to assume that U.S. human spaceflight would continue. 2 Committee on Human Spaceflight Crew Operations • FREDERICK GREGORY, Lohfeld Consulting Group, Inc., Co-Chair • JOSEPH H. ROTHENBERG, Swedish Space Corporation, Co-Chair • MICHAEL J. CASSUTT, University of Southern California • RICHARD O. COVEY, United Space Alliance, LLC (retired) • DUANE DEAL, Stinger Ghaffarian Technologies, Inc. • BONNIE J. DUNBAR, President and CEO, Dunbar International, LLC • WILLIAM W. HOOVER, Independent Consultant • THOMAS D. JONES, Florida Institute of Human and Machine Cognition • FRANKLIN D. MARTIN, Martin Consulting, Inc. -

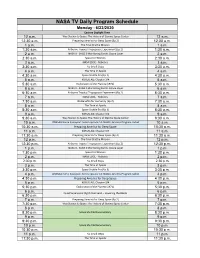

NASA TV Schedule for Web (Week of 6-22-2020).Xlsx

NASA TV Daily Program Schedule Monday - 6/22/2020 Eastern Daylight Time 12 a.m. Way Station to Space: The History of Stennis Space Center 12 a.m. 12:30 a.m. Preparing America for Deep Space (Ep.2) 12:30 a.m. 1 a.m. The Final Shuttle Mission 1 a.m. 1:30 a.m. Airborne Tropical Tropopause Experiment (Ep.2) 1:30 a.m. 2 a.m. NASA X - SAGE 3 Monitoring Earths Ozone Layer 2 a.m. 2:30 a.m. Space for Women 2:30 a.m. 3 a.m. NASA EDGE - Robotics 3 a.m. 3:30 a.m. No Small Steps 3:30 a.m. 4 a.m. The Time of Apollo 4 a.m. 4:30 a.m. Space Shuttle Era (Ep.3) 4:30 a.m. 5 a.m. KORUS-AQ: Chapter 3/4 5 a.m. 5:30 a.m. Exploration of the Planets (1971) 5:30 a.m. 6 a.m. NASA X - SAGE 3 Monitoring Earths Ozone Layer 6 a.m. 6:30 a.m. Airborne Tropical Tropopause Experiment (Ep.2) 6:30 a.m. 7 a.m. NASA EDGE - Robotics 7 a.m. 7:30 a.m. ISS Benefits for Humanity (Ep.2) 7:30 a.m. 8 a.m. The Time of Apollo 8 a.m. 8:30 a.m. Space Shuttle Era (Ep.3) 8:30 a.m. 9 a.m. KORUS-AQ: Chapter 3/4 9 a.m. 9:30 a.m. Way Station to Space: The History of Stennis Space Center 9:30 a.m. -

Feasibility Study and Future Projections of Suborbital Space Tourism at the Example of Virgin Galactic

Matthias Otto Feasibility Study and Future Projections of Suborbital Space Tourism at the Example of Virgin Galactic Diplom.de Matthias Otto Feasibility Study and Future Projections of Suborbital Space Tourism at the Example of Virgin Galactic ISBN: 978-3-8366-1723-9 Herstellung: Diplomica® Verlag GmbH, Hamburg, 2008 Dieses Werk ist urheberrechtlich geschützt. Die dadurch begründeten Rechte, insbesondere die der Übersetzung, des Nachdrucks, des Vortrags, der Entnahme von Abbildungen und Tabellen, der Funksendung, der Mikroverfilmung oder der Vervielfältigung auf anderen Wegen und der Speicherung in Datenverarbeitungsanlagen, bleiben, auch bei nur auszugsweiser Verwertung, vorbehalten. Eine Vervielfältigung dieses Werkes oder von Teilen dieses Werkes ist auch im Einzelfall nur in den Grenzen der gesetzlichen Bestimmungen des Urheberrechtsgesetzes der Bundesrepublik Deutschland in der jeweils geltenden Fassung zulässig. Sie ist grundsätzlich vergütungspflichtig. Zuwiderhandlungen unterliegen den Strafbestimmungen des Urheberrechtes. Die Wiedergabe von Gebrauchsnamen, Handelsnamen, Warenbezeichnungen usw. in diesem Werk berechtigt auch ohne besondere Kennzeichnung nicht zu der Annahme, dass solche Namen im Sinne der Warenzeichen- und Markenschutz-Gesetzgebung als frei zu betrachten wären und daher von jedermann benutzt werden dürften. Die Informationen in diesem Werk wurden mit Sorgfalt erarbeitet. Dennoch können Fehler nicht vollständig ausgeschlossen werden und der Verlag, die Autoren oder Übersetzer übernehmen keine juristische Verantwortung oder irgendeine Haftung für evtl. verbliebene fehlerhafte Angaben und deren Folgen. © Diplomica Verlag GmbH http://www.diplomica.de, Hamburg 2008 Acknowledgements This work would not have been possible without the contribution of a great number of people that made themselves available for interviews and thus helped me with my investigations on suborbital space tourism. In particular, I am deeply grateful to the following persons: Dr. -

NASA Langley Research Center

National Aeronautics and Space Administration LANGLEY RESEARCH CENTER www.nasa.gov contents NASA is on a reinvigorated “path of exploration, innovation and technological development leading to an array of challenging destinations and missions. — Charles Bolden” NASA Administrator Director’s Message ........................................ 2-3 Exploration Developing a New Launch Crew Vehicle ................. 4-5 Aeronautics Forging Tomorrow’s Flight Today ............................... 6 NASA Tests Biofuels for Commercial Jets .................. 7 Science Tracking Dynamic Change ......................................... 8 Airborne Air-Quality Campaign Created a Buzz ........... 9 Systems Analysis Making the Complex Work ...................................... 10 Partnerships Collaborating to Transition NASA Technologies .......................................... 12-13 We Have Liftoff Two Launches Carried Langley Instruments into Space ..................................... 14-15 A Space Shuttle Tribute ........................... 16-17 Economics ................................................... 18-19 Langley People ........................................... 20-21 Outreach & Education .............................. 22-23 Awards & Patents ...................................... 24-26 Contacts/Leadership ...................................... 27 Virginia Air & Space Center ........................... 27 (Inside cover) Splashdown of a crew A conference room in Langley’s new headquarters capsule mockup in Langley’s new Hydro building uses -

Technology Demonstration Mission Program

National Aeronautics and Space Administration Technology Demonstration Mission Program Volume 1, Issue 1 The Bridge January–February 2013 An artist’s rendering of the Ball smallsat, set to carry the Green Propellant Infusion Green Propellant Infusion Mission to space for flight-testing in 2015. Mission Joins TDM With this award, NASA has expanded (Image: Ball Aerospace) Project Family the scope of TDM to pursue environ- mentally friendly technologies. Mission Late last summer, NASA selected researchers will deliver a cheaper, safer, NASA’s Supersonic Ball Aerospace & Technologies Corp. more powerful alternative to the toxic, of Boulder, Colo., to lead its newest corrosive propellant hydrazine. Decelerator Project Technology Demonstration Mission ‘On Track’ for Success project: the Green Propellant Infusion Read all about the newest TDM project NASA has completed three key Mission. here. milestones in its development of new atmospheric deceleration technologies MEDLI On the ‘EDGE’ Data from the sensors, now being to support exploration missions across studied by MEDLI researchers, will the solar system. The Mars Science Laboratory Entry, help NASA engineers design safer, Descent & Landing Instrumentation, more lightweight entry systems for The Low-Density Supersonic Decel- or MEDLI, was the subject of a recent future Mars missions — ones carry- erator project, which is developing video feature by NASA EDGE, the ing human crews as well as robotic technologies to use atmospheric agency’s offbeat, informative video- explorers. drag to dramatically slow a vehicle podcast series. as it penetrates the skies over worlds Watch the complete NASA EDGE feature beyond our own, completed three NASA EDGE visited the MEDLI team on MEDLI here. -

GAO-05-230 Space Shuttle: Actions Needed to Better Position

United States Government Accountability Office Report to Congressional Requesters GAO March 2005 SPACE SHUTTLE Actions Needed to Better Position NASA to Sustain Its Workforce through Retirement GAO-05-230 March 2005 SPACE SHUTTLE Accountability Integrity Reliability Highlights Actions Needed to Better Position NASA Highlights of GAO-05-230, a report to to Sustain Its Workforce through congressional requesters Retirement Why GAO Did This Study What GAO Found The President’s vision for space The Space Shuttle Program has made limited progress toward developing a exploration (Vision) directs the detailed long-term strategy for sustaining its workforce through the space National Aeronautics and Space shuttle’s retirement. The program has taken preliminary steps, including Administration (NASA) to retire the identifying the lessons learned from the retirement of programs comparable space shuttle following completion to the space shuttle, such as the Air Force Titan IV Rocket Program, to assist of the International Space Station, planned for the end of the decade. in its workforce planning efforts. Other efforts have been initiated or are The retirement process will last planned, such as enlisting the help of human capital experts and revising the several years and impact thousands acquisition strategy for updating the space shuttle’s propulsion system prime of critically skilled NASA civil contracts; however, actions taken thus far have been limited. NASA’s prime service and contractor employees contractor for space shuttle operations has also taken some preliminary that support the program. Key to steps to begin to prepare for the impact of the space shuttle’s retirement on implementing the Vision is NASA’s its workforce, such as working with a consulting firm to conduct a ability to sustain this workforce to comprehensive study of its workforce. -

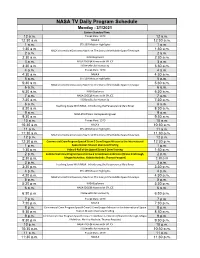

NASA TV Schedule for Web (Week of 3-1-2021).Xlsx

NASA TV Daily Program Schedule Monday - 3/1/2021 Eastern Standard Time 12 a.m. Planet Mars: 1979 12 a.m. 12:30 a.m. NASA X 12:30 a.m. 1 a.m. STS-109 Mission Highlights 1 a.m. 1:30 a.m. 1:30 a.m. NASA’s Incredible Discovery Machine: The Story of the Hubble Space Telescope 2 a.m. 2 a.m. 2:30 a.m. NASA Explorers 2:30 a.m. 3 a.m. NASA EDGE@ Home with SPLICE 3 a.m. 3:30 a.m. ISS Benefits for Humanity 3:30 a.m. 4 a.m. Planet Mars: 1979 4 a.m. 4:30 a.m. NASA X 4:30 a.m. 5 a.m. STS-109 Mission Highlights 5 a.m. 5:30 a.m. 5:30 a.m. NASA’s Incredible Discovery Machine: The Story of the Hubble Space Telescope 6 a.m. 6 a.m. 6:30 a.m. NASA Explorers 6:30 a.m. 7 a.m. NASA EDGE@ Home with SPLICE 7 a.m. 7:30 a.m. ISS Benefits for Humanity 7:30 a.m. 8 a.m. 8 a.m. Teaching Space With NASA - Introducing the Perseverance Mars Rover 8:30 a.m. 8:30 a.m. 9 a.m. NASA STEM Stars: Aerospace Engineer 9 a.m. 9:30 a.m. 9:30 a.m. 10 a.m. Planet Mars: 1979 10 a.m. 10:30 a.m. NASA X 10:30 a.m. 11 a.m. STS-109 Mission Highlights 11 a.m. 11:30 a.m. -

Challenger Accident in a Rogers Commission Hearing at KSC

CHALLENGER By Arnold D. Aldrich Former Program Director, NSTS August 27, 2008 Recently, I was asked by John Shannon, the current Space Shuttle Program Manager, to comment on my experiences, best practices, and lessons learned as a former Space Shuttle program manager. This project is part of a broader knowledge capture and retention initiative being conducted by the NASA Johnson Space Center in an “oral history” format. One of the questions posed was to comment on some of the most memorable moments of my time as a Space Shuttle program manager. Without question, the top two of these were the launch of Challenger on STS‐51L on January 28, 1986, and the launch of Discovery on STS‐26 on September 29, 1988. Background The tragic launch and loss of Challenger occurred over 22 years ago. 73 seconds into flight the right hand Solid Rocket Booster (SRB) broke away from the External Tank (ET) as a result of a burn‐ through in its aft most case to case joint and the Space Shuttle vehicle disintegrated resulting in the total loss of the vehicle and crew. The events leading up to that launch are still vivid in my mind and deeply trouble me to this day, as I know they always will. This paper is not about what occurred during the countdown leading up to the launch – those facts and events were thoroughly investigated and documented by the Rogers Commission. Rather, what I can never come to closure with is how we, as a launch team, and I, as one of the leaders of that team, allowed the launch to occur. -

Space Planes and Space Tourism: the Industry and the Regulation of Its Safety

Space Planes and Space Tourism: The Industry and the Regulation of its Safety A Research Study Prepared by Dr. Joseph N. Pelton Director, Space & Advanced Communications Research Institute George Washington University George Washington University SACRI Research Study 1 Table of Contents Executive Summary…………………………………………………… p 4-14 1.0 Introduction…………………………………………………………………….. p 16-26 2.0 Methodology…………………………………………………………………….. p 26-28 3.0 Background and History……………………………………………………….. p 28-34 4.0 US Regulations and Government Programs………………………………….. p 34-35 4.1 NASA’s Legislative Mandate and the New Space Vision………….……. p 35-36 4.2 NASA Safety Practices in Comparison to the FAA……….…………….. p 36-37 4.3 New US Legislation to Regulate and Control Private Space Ventures… p 37 4.3.1 Status of Legislation and Pending FAA Draft Regulations……….. p 37-38 4.3.2 The New Role of Prizes in Space Development…………………….. p 38-40 4.3.3 Implications of Private Space Ventures…………………………….. p 41-42 4.4 International Efforts to Regulate Private Space Systems………………… p 42 4.4.1 International Association for the Advancement of Space Safety… p 42-43 4.4.2 The International Telecommunications Union (ITU)…………….. p 43-44 4.4.3 The Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space (COPUOS).. p 44 4.4.4 The European Aviation Safety Agency…………………………….. p 44-45 4.4.5 Review of International Treaties Involving Space………………… p 45 4.4.6 The ICAO -The Best Way Forward for International Regulation.. p 45-47 5.0 Key Efforts to Estimate the Size of a Private Space Tourism Business……… p 47 5.1.