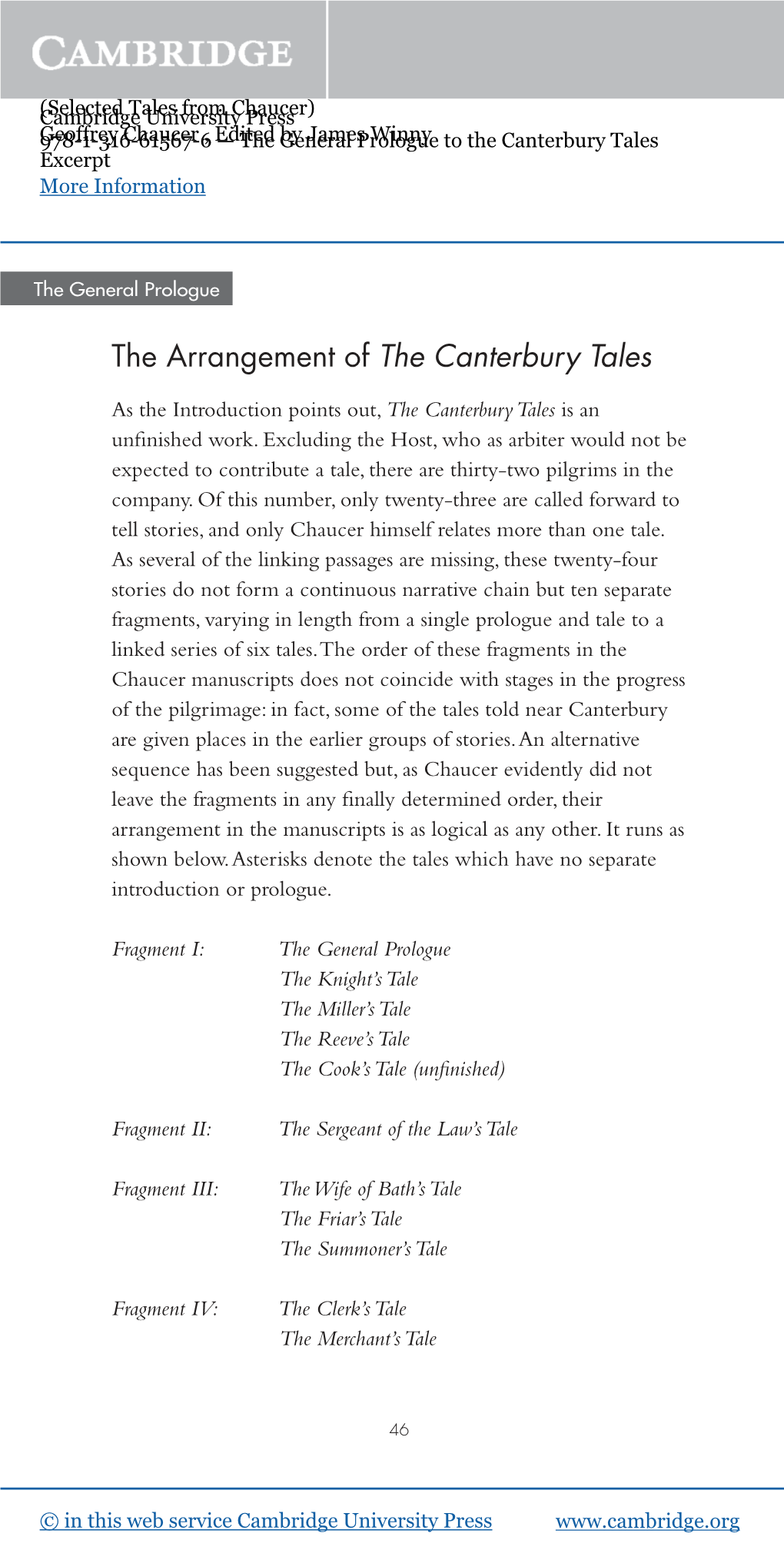

The Arrangement of the Canterbury Tales

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Queer Fantasies of Normative Masculinity in Middle English Popular Romance

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 2014 The Queer Fantasies of Normative Masculinity in Middle English Popular Romance Cathryn Irene Arno The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Arno, Cathryn Irene, "The Queer Fantasies of Normative Masculinity in Middle English Popular Romance" (2014). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 4167. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/4167 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE QUEER FANTASIES OF NORMATIVE MASCULINITY IN MIDDLE ENGLISH POPULAR ROMANCE By CATHRYN IRENE ARNO Bachelor of Arts, University of Montana, Missoula, 2008 Thesis presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in English Literature The University of Montana Missoula, MT December 2013 Approved by: Sandy Ross, Dean of The Graduate School Graduate School Dr. Ashby Kinch, Chair Department of English Dr. Elizabeth Hubble, Department of Women’s and Gender Studies Dr. John Hunt, Department of English © COPYRIGHT by Cathryn Irene Arno 2014 All Rights Reserved ii Arno, Cathryn, M.A., Fall 2013 English The Queer Fantasies of Normative Masculinity in Middle English Popular Romance Chairperson: Dr. Ashby Kinch This thesis examines how the authors, Geoffrey Chaucer and Thomas Chestre, manipulate the construct of late fourteenth-century normative masculinity by parodying the aristocratic ideology that hegemonically prescribed the proper performance of masculine normativity. -

Wife of Bath, Pardoner and Sir Thopas : Pre- Texts and Para-Texts

Wife of Bath, Pardoner and Sir Thopas : pre- texts and para-texts Autor(en): Taylor, Paul B. Objekttyp: Article Zeitschrift: SPELL : Swiss papers in English language and literature Band (Jahr): 3 (1987) PDF erstellt am: 03.10.2021 Persistenter Link: http://doi.org/10.5169/seals-99852 Nutzungsbedingungen Die ETH-Bibliothek ist Anbieterin der digitalisierten Zeitschriften. Sie besitzt keine Urheberrechte an den Inhalten der Zeitschriften. Die Rechte liegen in der Regel bei den Herausgebern. Die auf der Plattform e-periodica veröffentlichten Dokumente stehen für nicht-kommerzielle Zwecke in Lehre und Forschung sowie für die private Nutzung frei zur Verfügung. Einzelne Dateien oder Ausdrucke aus diesem Angebot können zusammen mit diesen Nutzungsbedingungen und den korrekten Herkunftsbezeichnungen weitergegeben werden. Das Veröffentlichen von Bildern in Print- und Online-Publikationen ist nur mit vorheriger Genehmigung der Rechteinhaber erlaubt. Die systematische Speicherung von Teilen des elektronischen Angebots auf anderen Servern bedarf ebenfalls des schriftlichen Einverständnisses der Rechteinhaber. Haftungsausschluss Alle Angaben erfolgen ohne Gewähr für Vollständigkeit oder Richtigkeit. Es wird keine Haftung übernommen für Schäden durch die Verwendung von Informationen aus diesem Online-Angebot oder durch das Fehlen von Informationen. Dies gilt auch für Inhalte Dritter, die über dieses Angebot zugänglich sind. Ein Dienst der ETH-Bibliothek ETH Zürich, Rämistrasse 101, 8092 Zürich, Schweiz, www.library.ethz.ch http://www.e-periodica.ch Wife of Bath, Pardoner and Sir Tbopas: Pre-Texts and Para-Texts Paul B. Taylor The Canterbury Tales are neither a miscellany of medieval narratives nor a concatenated roadside drama of a group of pilgrims. The meaning of each tale interacts with the sense of the work as a whole, and it is the context of a telling that informs it with purpose and directs reading. -

Pawn Captures Knighthood: the Tale of Sir Thopas As a Commentary on the Rise of Peasants to Knighthood and the Deterioration of Chivalry

JUSTIN SINGER Pawn Captures Knighthood: The Tale of Sir Thopas as a Commentary on the Rise of Peasants to Knighthood and the Deterioration of Chivalry ABSTRACT The Tale of Sir Thopas, one of Geoffrey Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales, contains many details which are inversions of the traditional portrayal of knights in chansons de geste. The reason for these inversions must be determined by interpreting the various details of the portrayal of the protagonist, Sir Thopas, within the historical context of England during the late fourteenth century. During this time period in England, the Black Death had precipitated dramatic changes in social hierarchy. The drastic decline in population led many members of the established nobility to fall into economic distress as a result of labour shortages, and the rise in the value of labour meant that individuals of common birth were no longer as ubiquitous and expendable as they had previously been. Newly wealthy non-nobles were thereby able to rise to the rank of knighthood. This paper shall examine the symbolic details in the Tale of Sir Thopas in relation to their historical context of Medieval England in the years following the plague, and thereby demonstrate that the Tale of Sir Thopas is a commentary on the rise of common born knights and the resulting decline of chivalric values. In The Tale of Sir Thopas, a Canterbury Tale, one of Chaucer’s Pilgrims recites an asinine poem which mocks the traditional Chansons de Geste in both metre and content. The Tale of Sir Thopas is about an effeminate Flemish knight who must slay a three-headed giant in order to marry an elf queen. -

The Canterbury Tales: a Girardian Reading

Desire, Violence, and the Passion in Fragment VII of The Canterbury Tales: A Girardian Reading Curtis Gruenler, Hope College Published in Renascence: A Journal of Values in Literature 52.1 (Fall 1999): 35-56. 1 The most successful attempts to demonstrate the unity of Fragment VII of Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales , the longest and most diverse grouping of tales as they have come down to us, have treated it as a statement of Chaucer’s artistic principles. Alan Gaylord’s influential view of this as “the Literature Group” emphasizes how the links between these six tales give us, through the Host of the tale-telling contest, Harry Bailly, a counterexample of how Chaucer would have us read his tales: “if Harry is the Apostle of the Obvious, Chaucer is the Master of Indirection” (235). Adroitly pursuing the Master of Indirection further into his self-presentation as teller of the two tales at the center this fragment, Lee Patterson has argued that Chaucer frames a modern vision of autonomous literature as opposed to the courtly or didactic and represents, through the recurrent figure of the child, a corresponding subjectivity that both transcends and suffers history (“What man artow?” 162-4). Yet beyond their author’s literary aims and subjectivity, I want to argue, the tales of Fragment VII as a group also address a problem in the world outside the text—the problem of human violence—and probe the potential of literature to perpetuate or remedy this problem. In the late fourteenth century, violence on a large scale held English attention as spectacular victories against the French early in the Hundred Years War were followed by a series of costly, disastrous campaigns. -

Sir Thopas Imagining the World in Maps and Stories: Sir Thopas William M

Sir Thopas Imagining the World in Maps and Stories: Sir Thopas William M. Storm ([email protected]) An essay chapter for The Open Access Companion to the Canterbury Tales (September 2017) Introduction Texts, just like travelers, sometimes lose their way. We have all had the experience of reading something—be it a classmate’s essay, an essay in a companion piece, a novel, or something else—and we are not quite sure where things are going. This might be that the author has introduced an idea that distracts from the main point, or it might simply be that we as readers do not understand the connections between ideas. Either way, as readers, we look for the text to get back on track. As Chaucer begins to recount his Tale of Sir Thopas, the characters have just heard the Prioress’s Tale, detailing the grisly murder of a young boy. As you know from the previous essay, it is a hagiographic tale of a miracle made possible through the intervention of the Virgin Mary. Though it fits within a tradition of miracle literature, it seems out of place with much of what we have heard in the Canterbury Tales and our group of pilgrims, “every man / As sobre was that wonder was to se” (Th 691-92). In other words, the Prioress’s story has sobered up everyone—the narrator tells us that it is a kind of miracle itself—and everyone is now silent. So what should happen next? The Prioress’s Tale has effectively stopped the storytelling because the pilgrims are not sure what to say next. -

The Canterbury Tales

The Canterbury Tales Geoffrey Chaucer The Canterbury Tales Table of Contents The Canterbury Tales.........................................................................................................................................1 Geoffrey Chaucer.....................................................................................................................................1 i The Canterbury Tales Geoffrey Chaucer • Prologue • The Knight's Tale • The Miller's Prologue • The Miller's Tale • The Reeve's Prologue • The Reeve's Tale • The Cook's Prologue • The Cook's Tale • Introduction To The Lawyer's Prologue • The Lawyer's Prologue • The Lawyer's Tale • The Sailor's Prologue • The Sailor's Tale • The Prioress's Prologue • The Prioress's Tale • Prologue To Sir Thopas • Sir Thopas • Prologue To Melibeus • The Tale Of Melibeus • The Monk's Prologue • The Monk's Tale • The Prologue To The Nun's Priest's Tale • The Nun's Priest's Tale • Epilogue To The Nun's Priest's Tale • The Physician's Tale • The Words Of The Host • The Prologue To The Pardoner's Tale • The Pardoner's Tale • The Wife Of Bath's Prologue • The Tale Of The Wife Of Bath • The Friar's Prologue • The Friar's Tale • The Summoner's Prologue • The Summoner's Tale • The Clerk's Prologue • The Clerk's Tale • The Merchant's Prologue • The Merchant's Tale • Epilogue To The Merchant's Tale • The Squire's Prologue • The Squire's Tale • The Words Of The Franklin And The Host • The Franklin's Prologue • The Franklin's Tale • The Second Nun's Prologue • The Second Nun's Tale The Canterbury Tales 1 The Canterbury Tales • The Canon's Yeoman's Prologue • The Canon's Yeoman's Tale • The Manciple's Prologue • The Manciple's Tale Of The Crow • The Parson's Prologue • The Parson's Tale • The Maker Of This Book Takes His Leave This page copyright © 1999 Blackmask Online. -

The Canterbury Tales

The Canterbury Tales Geoffrey Chaucer The Canterbury Tales Table of Contents The Canterbury Tales.........................................................................................................................................1 Geoffrey Chaucer.....................................................................................................................................1 i The Canterbury Tales Geoffrey Chaucer • Prologue • The Knight's Tale • The Miller's Prologue • The Miller's Tale • The Reeve's Prologue • The Reeve's Tale • The Cook's Prologue • The Cook's Tale • Introduction To The Lawyer's Prologue • The Lawyer's Prologue • The Lawyer's Tale • The Sailor's Prologue • The Sailor's Tale • The Prioress's Prologue • The Prioress's Tale • Prologue To Sir Thopas • Sir Thopas • Prologue To Melibeus • The Tale Of Melibeus • The Monk's Prologue • The Monk's Tale • The Prologue To The Nun's Priest's Tale • The Nun's Priest's Tale • Epilogue To The Nun's Priest's Tale • The Physician's Tale • The Words Of The Host • The Prologue To The Pardoner's Tale • The Pardoner's Tale • The Wife Of Bath's Prologue • The Tale Of The Wife Of Bath • The Friar's Prologue • The Friar's Tale • The Summoner's Prologue • The Summoner's Tale • The Clerk's Prologue • The Clerk's Tale • The Merchant's Prologue • The Merchant's Tale • Epilogue To The Merchant's Tale • The Squire's Prologue • The Squire's Tale • The Words Of The Franklin And The Host • The Franklin's Prologue • The Franklin's Tale • The Second Nun's Prologue • The Second Nun's Tale The Canterbury Tales 1 The Canterbury Tales • The Canon's Yeoman's Prologue • The Canon's Yeoman's Tale • The Manciple's Prologue • The Manciple's Tale Of The Crow • The Parson's Prologue • The Parson's Tale • The Maker Of This Book Takes His Leave This page copyright © 1999 Blackmask Online. -

The Prioress and Her Tale

PRIORESS’S TALE 1 THE PRIORESS AND HER TALE and The Words of the Host to Chaucer the Pilgrim The Interruption of Chaucer's Tale of Sir Thopas The Epilogue to the Tale of Melibee The Prologue to the Tale of the Monk PRIORESS’S TALE 1 The Prioress is the head of a fashionable convent. She is a charming lady, none the less charming for her slight worldliness: she has a romantic name, Eglantine, wild rose; she has delicate table manners and is exquisitely sensitive to animal rights; she speaks French -- after a fashion; she has a pretty face and knows it; her nun's habit is elegantly tailored, and she displays discreetly a little tasteful jewelry: a gold brooch on her rosary embossed with the nicely ambiguous Latin motto: Amor Vincit Omnia, Love conquers all. Here is the description of the Prioress from the General Prologue There was also a nun, a PRIORESS, head of a convent That of her smiling was full simple and coy. modest 120 Her greatest oath was but by Saint Eloy,1 And she was clep•d Madame Eglantine. called Full well she sang the servic• divine Entun•d in her nose full seem•ly.2 And French she spoke full fair and fetisly nicely 125 After the school of Stratford at the Bow, For French of Paris was to her unknow.3 Her good manners At meat• well y-taught was she withall: meals / indeed She let no morsel from her lipp•s fall, Nor wet her fingers in her sauc• deep. -

Where Are Chaucer's “Retracciouns”?

FLORILEGIUM 10, 1988-91 WHERE ARE CHAUCER’S “RETRACCIOUNS”? Victor Yelverton Haines Chaucer s retracciouns” are to be found throughout his work where he ironically presents a meaning from which he pulls back, withdraws, or re tracts. In the difference between the meaning retracted from and the right meaning “retracted to,” the reader’s response is exercised in an ethical test. Chaucer’s good “entente” engages the reader in the rhetoric of “retraccioun” as it applies throughout his work and not just in what has been called his “Retraction” at the end of “The Parson’s Tale.”1 When Chaucer the scriptor writes of his conversation with the Monk, for example, “And I seyde his opinion was good,” Chaucer’s intention in its ethical context is to pull the reader back, to retract, from a straight reading that the Monk’s opinion is in fact good. This is one of many of Chaucer’s “retracciouns,” as he refers to them in the plural at the end of The Canter bury Tales in the Epilogue to “The Parson’s Tale.” In fact, the meaning we are familiar with in the so-called “Retraction,” that Chaucer wished to re tract or annul the works themselves, is itself a meaning from which Chaucer intended us to retract. It is there in the text just as the meaning that the Monk s opinion is good is in the text, and Chaucer intended it to be there: it would protect him from vicious censors. But he also intended a more subtle and moral meaning for the “Retraction,” which modern readers by and large have missed. -

The Change in Chaucerian Aesthetics: from the Tale of Sir Thopas to the Tale of Melibee

DOI: 10.13114/MJH.2017.367 Geliş Tarihi: 23.04.2017 Mediterranean Journal of Humanities Kabul Tarihi: 11.23.2017 mjh.akdeniz.edu.tr VII/2 (2017) 337-346 The Change in Chaucerian Aesthetics: From The Tale of Sir Thopas to The Tale of Melibee Chaucer Estetiğindeki Değişim: Sir Thopas’ın Hikayesi’nden Melibee’nin Hikayesi’ne Oya BAYILTMIŞ ÖĞÜTCÜ Abstract: Chaucer‟s The Tale of Sir Thopas and The Tale of Melibee exhibit the transformation from the romance tradition to philosophical narration, exaggerating romance as an unrealistic narration and presenting philosophical narration as a more realistic literary form. Chaucer the pilgrim firstly starts with romance (The Tale of Sir Thopas) and then continues with a philosophical tale (The Tale of Melibee), which is derived from Boethius‟s Consolation of Philosophy. In this respect, the role of Chaucer the pilgrim is very important to display the change in Chaucerian literary aesthetics. Furthermore, displaying the negative attitudes of the pilgrims, as a representative audience, towards The Tale of Sir Thopas, which starts with the interruption of the tale, and the positive remarks of the pilgrims towards The Tale of Melibee, Chaucer exhibits the reception process of his tales, which can be defined as the reflection of the literary aesthetics not only of the poet but also on the part of the audience/readers. Hence, it can be suggested that, presenting the approval of a more realistic philosophical narrative, Chaucer not only reflects the change in literary aesthetics, but also shapes this change in literary aesthetics. Thus, the aim of this article is to discuss the literary aesthetics of the change from romance to philosophical narration, and to claim that this representation of literary aesthetics is functional in displaying Chaucer‟s literary self- fashioning. -

Laughing at Knights: Representations of Humour in Sir Perceval of Galles, Sir Beues of Hamtoun, Lybeaus Desconus and Geoffrey Chaucer’S Tale of Sir Thopas

DOI: 10.13114/MJH.2016119307 Tarihi: 31.03.2016 Mediterranean Journal of Humanities Kabul Tarihi: 20.06.2016 Geliş mjh.akdeniz.edu.tr VI/1 (2016) 309-322 Laughing at Knights: Representations of Humour in Sir Perceval of Galles, Sir Beues of Hamtoun, Lybeaus Desconus and Geoffrey Chaucer’s Tale of Sir Thopas Şövalyelere Gülmek: Sir Perceval of Galles, Sir Beues of Hamtoun, Lybeaus Desconus ve Geoffrey Chaucer’ın Sir Thopas’ın Hikayesi’nde Mizah Betimlemeleri Pınar TAŞDELEN∗ Abstract: Romance conventions, motifs and archetypes blend in order to appeal to the moral concerns of the romance audience. In particular, chivalric romances are heroic narratives adapted to English feudalism and the Christian faith, either to depict a knight’s moral progress or the aristocratic way of life; therefore, romance would seem to be the last place one would look for humour. Much of the humour in medieval romance is the effect of the exaggeration of heroic expressions and deeds, which then becomes mocking and ridiculous rather than heroic. This article concentrates on the representations of humour in Sir Perceval of Galles, Sir Beues of Hamtoun, Lybeaus Desconus and Geoffrey Chaucer’s Tale of Sir Thopas. It discusses what makes these romances humorous, how the romance heroes are presented as laughable figures, while it argues the function of humour in these romances. The romance heroes and situations are compared, and they are presented in detail with specific examples from these romances. Romance as a humorous genre is discussed as to if its use is for humour as a means of laughter, for satire or for emphasis upon the idea of chivalry. -

The Tale of Sir Thopas /1

The Tale of Sir Thopas /1 The Tale of Sir Thopas1 The Introduction Whan said was al this miracle,2 every man As sobre was that wonder was to see, Til that oure Hoste japenЊ he bigan, joke And thanne at erstЊ he looked upon me, for the first time 5 And saide thus, “What man artou?”Њ quod he. art thou “Thou lookest as thou woldest finde an hare, For evere upon the ground I see thee stare. Approche neer and looke up merily. Now ware you, sires, and lat this man have place: 10 He in the wast is shape as wel as I— This were a popetЊ in an arm t’ enbrace, doll For any womman, smal and fair of face; He seemeth elvisshЊ by his countenaunce, elfin For unto no wight dooth he daliaunce.Њ makes conversation 15 Say now somwhat, sinЊ other folk han said. since Tel us a tale of mirthe, and that anoon.” “Hoste,” quod I, “ne beeth nat yvele apaid,3 For other tale, certes, canЊ I noon, know But of a rym I lerned longe agoon.” 20 “Ye, that is good,” quod he. “Now shul we heere Som dainteeЊ thing, me thinketh by his cheere.”Њ delightful / face The Tale Listeth,Њ lordes, in good entent, listen And I wil telle verraymentЊ truly 1. The Tale of Sir Thopas is a burlesque of popular exercise in brilliant monotony and witty banality. romances. These were stripped-down, cliche´- But within the frame story of the Canterbury ridden versions of French chivalric romances, Tales, Chaucer’s parody turns into a truly Olym- composed and recited by minstrels for unsophis- pian jest about the nature of art and artists.