Mother of Gardens” Pursuing Seeds and Specimens in Sichuan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Astilbe Chinensis 'Visions'

cultureconnection perennial solutions Astilbe chinensis ‘Visions’ This deer-resistant variety also attracts hummingbirds and can be utilized in your marketing programs. stilbes are very erect to arching, plume-like flower during the spring or fall. For By Paul Pilon popular shade panicles that rise above the foliage quart production, a crown con- and woodland on slender upright stems. Astilbe sisting of 1-2 eyes, or shoots, is garden perenni- chinensis ‘Visions’ is a showy culti- commonly used. For larger con- als. They form var that forms compact foliage tainers, such as a 1-gal., divisions beautiful mounds of fern-like mounds with green to bronze- containing 2-3 eyes are commonly foliage bearing tiny flowers on green glossy leaves reaching 9-12 used. In most cases, container inches high. Flowering occurs in growers do not propagate astilbe early summer, forming pyramidal- cultivars; rather, they purchase A shaped 14- to 16-inch-tall plumes bareroot divisions or large plug full of small, fragrant, raspberry- liners from growers who special- red flowers. Astilbes are often ize in astilbe propagation. used for cut flowers, as container ‘Visions’ is not a patented culti- items, in mass plantings or small var and can be propagated by any groups, as border plants and as grower. There are two fairly new groundcovers in shade gardens. introductions with the Visions ‘Visions’ can be easily produced name, ‘Vision in Pink’ and ‘Vision in average, medium-wet, well- in Red’; these are patented culti- drained soils across USDA vars. Growers should note that Hardiness Zones 4-9 and AHS unlicensed propagation of these Heat Zones 8-2. -

Perennials for Special Purposes

Perennials for Special Purposes Hot & Dry Areas • Sage, Perennial (Artemisia) Newly planted perennials will need regular • Sea Holly (Eryngium) watering until established. • Sea Lavender (Limonium) • Spurge, Cushion (Euphorbia • Aster polychroma) • Baby’s Breath • Statice, German (Gypsophila) (Goniolimon) • Beardtongue • Stonecrop (Sedum) (Penstemon) • Sunflower, False (Heliopsis) • Big Bluestem • Sunflower, Perennial (Helianthus) (Andropogon) • Switch Grass (Panicum) • Bitterroot (Lewisia) • Tickseed (Coreopsis) • Blanketflower (Gaillardia) • Tufted Hair Grass (Deschampsia) • Blue Oat Grass (Helictotrichon) • Yarrow (Achillea) • Cactus, Prickly Pear (Opuntia) • Yucca • Candytuft (Iberis sempervirens) • Cinquefoil (Potentilla) Groundcover for Sun • Coneflower (Echinacea) • Daisy, Painted (Tanacetum) • Baby’s Breath, Creeping • Daisy, Shasta (Leucanthemum x superbum) (Gypsophila repens) • Daylily (Hemerocallis) • Beardtongue, Spreading • Evening Primrose (Oenothera) (Penstemon) • False Indigo (Baptisia) • Bellflower, Spreading • Feather Reed Grass (Calamagrostis) (Campanula) • Fescue, Blue (Festuca glauca) • Cinquefoil (Potentilla) • Flax (Linum) • Cliff Green (Paxistima • Foxtail Lily (Eremurus) canbyi) • Globe Thistle (Echinops) • Cranesbill (Geranium) • Goldenrod (Solidago) • Gentian, Trumpet (Gentiana acaulis) • Helen’s Flower (Helenium) • Globe Daisy (Globularia) • Hens & Chicks (Sempervivum) • Hens & Chicks (Sempervivum) • Ice Plant (Delosperma) • Irish/Scotch Moss (Sagina subulata) • Lamb’s Ears (Stachys byzantina) • Kinnikinnick -

THE Magnoliaceae Liriodendron L. Magnolia L

THE Magnoliaceae Liriodendron L. Magnolia L. VEGETATIVE KEY TO SPECIES IN CULTIVATION Jan De Langhe (1 October 2014 - 28 May 2015) Vegetative identification key. Introduction: This key is based on vegetative characteristics, and therefore also of use when flowers and fruits are absent. - Use a 10× hand lens to evaluate stipular scars, buds and pubescence in general. - Look at the entire plant. Young specimens, shade, and strong shoots give an atypical view. - Beware of hybridisation, especially with plants raised from seed other than wild origin. Taxa treated in this key: see page 10. Questionable/frequently misapplied names: see page 10. Names referred to synonymy: see page 11. References: - JDL herbarium - living specimens, in various arboreta, botanic gardens and collections - literature: De Meyere, D. - (2001) - Enkele notities omtrent Liriodendron tulipifera, L. chinense en hun hybriden in BDB, p.23-40. Hunt, D. - (1998) - Magnolias and their allies, 304p. Bean, W.J. - (1981) - Magnolia in Trees and Shrubs hardy in the British Isles VOL.2, p.641-675. - or online edition Clarke, D.L. - (1988) - Magnolia in Trees and Shrubs hardy in the British Isles supplement, p.318-332. Grimshaw, J. & Bayton, R. - (2009) - Magnolia in New Trees, p.473-506. RHS - (2014) - Magnolia in The Hillier Manual of Trees & Shrubs, p.206-215. Liu, Y.-H., Zeng, Q.-W., Zhou, R.-Z. & Xing, F.-W. - (2004) - Magnolias of China, 391p. Krüssmann, G. - (1977) - Magnolia in Handbuch der Laubgehölze, VOL.3, p.275-288. Meyer, F.G. - (1977) - Magnoliaceae in Flora of North America, VOL.3: online edition Rehder, A. - (1940) - Magnoliaceae in Manual of cultivated trees and shrubs hardy in North America, p.246-253. -

Magnolia 'Galaxy'

Magnolia ‘Galaxy’ The National Arboretum presents Magnolia ‘Galaxy’, unique in form and flower among cultivated magnolias. ‘Galaxy’ is a single-stemmed, tree-form magnolia with ascending branches, the perfect shape for narrow planting sites. In spring, dark red-purple flowers appear after danger of frost, providing a pleasing and long-lasting display. Choose ‘Galaxy’ to shape up your landscape! Winner of a Pennsylvania Horticultural Society Gold Medal Plant Award, 1992. U.S. National Arboretum Plant Introduction Floral and Nursery Plants Research Unit U.S. National Arboretum, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service, 3501 New York Ave. NE., Washington, DC 20002 ‘Galaxy’ hybrid magnolia Botanical name: Magnolia ‘Galaxy’ (M. liliiflora ‘Nigra’ × M. sprengeri ‘Diva’) (NA 28352.14, PI 433306) Family: Magnoliaceae Hardiness: USDA Zones 5–9 Development: ‘Galaxy’ is an F1 hybrid selection resulting from a 1963 cross between Magnolia liliiflora ‘Nigra’ and M. sprengeri ‘Diva’. ‘Galaxy’ first flowered at 9 years of age from seed. The cultivar name ‘Galaxy’ is registered with the American Magnolia Society. Released 1980. Significance: Magnolia ‘Galaxy’ is unique in form and flower among cultivated magnolias. It is a single stemmed, pyramidal, tree-form magnolia with excellent, ascending branching habit. ‘Galaxy’ flowers 2 weeks after its early parent M. ‘Diva’, late enough to avoid most late spring frost damage. Adaptable to a wide range of soil conditions. Description: Height and Width: 30-40 feet tall and 22-25 feet wide. It reaches 24 feet in height with a 7-inch trunk diameter at 14 years. Moderate growth rate. Habit: Single-trunked, upright tree with narrow crown and ascending branches. -

Number 3, Spring 1998 Director’S Letter

Planning and planting for a better world Friends of the JC Raulston Arboretum Newsletter Number 3, Spring 1998 Director’s Letter Spring greetings from the JC Raulston Arboretum! This garden- ing season is in full swing, and the Arboretum is the place to be. Emergence is the word! Flowers and foliage are emerging every- where. We had a magnificent late winter and early spring. The Cornus mas ‘Spring Glow’ located in the paradise garden was exquisite this year. The bright yellow flowers are bright and persistent, and the Students from a Wake Tech Community College Photography Class find exfoliating bark and attractive habit plenty to photograph on a February day in the Arboretum. make it a winner. It’s no wonder that JC was so excited about this done soon. Make sure you check of themselves than is expected to seedling selection from the field out many of the special gardens in keep things moving forward. I, for nursery. We are looking to propa- the Arboretum. Our volunteer one, am thankful for each and every gate numerous plants this spring in curators are busy planting and one of them. hopes of getting it into the trade. preparing those gardens for The magnolias were looking another season. Many thanks to all Lastly, when you visit the garden I fantastic until we had three days in our volunteers who work so very would challenge you to find the a row of temperatures in the low hard in the garden. It shows! Euscaphis japonicus. We had a twenties. There was plenty of Another reminder — from April to beautiful seven-foot specimen tree damage to open flowers, but the October, on Sunday’s at 2:00 p.m. -

Astilbe Thunbergii Reduces Postprandial Hyperglycemia in a Type 2 Diabetes Rat

1 Author’s pre-print manuscript of the following article 2 3 Astilbe thunbergii reduces postprandial hyperglycemia in a type 2 diabetes rat 4 model via pancreatic alpha-amylase inhibition by highly condensed 5 procyanidins. 6 7 Bioscience, Biotechnology, and Biochemistry, 2017, accepted. 8 Check the published version from the bellow link. 9 10 Taylers & Francis Online 11 DOI:10.1080/09168451.2017.1353403 12 http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/09168451.2017.1353403 13 14 15 1 16 E. Kato et al. 17 Anti-diabetic effect of Astilbe thunbergii 18 19 Research Article 20 Astilbe thunbergii reduces postprandial hyperglycemia in a type 2 diabetes 21 rat model via pancreatic alpha-amylase inhibition by highly condensed 22 procyanidins. 23 Eisuke Kato1*, Natsuka Kushibiki1, Yosuke Inagaki2, Mihoko Kurokawa2, Jun 24 Kawabata1 25 1Laboratory of Food Biochemistry, Division of Applied Bioscience, Graduate School 26 of Agriculture, Hokkaido University, Kita-ku, Sapporo, Hokkaido 060-8589, Japan 27 2Q'sai Co., Ltd., Kusagae, Fukuoka, Fukuoka 810-8606, Japan 28 29 *Corresponding author 30 Tel/Fax: +81 11 706 2496; 31 E-mail address: [email protected] (E. Kato) 32 2 33 Abstract 34 Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) is a common global health problem. Prevention 35 of this disease is an important task, and functional food supplements are 36 considered an effective method. Astilbe thunbergii extract (AT) was found to be a 37 potent pancreatic α-amylase inhibitor. AT treatment in a T2DM rat model 38 reduced post-starch administration blood glucose levels. Activity-guided 39 isolation revealed procyanidin as the active component with IC50 = 1.7 µg/mL 40 against porcine pancreatic α-amylase. -

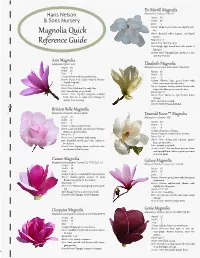

Magnolia Quick Reference Guide

MagnoliaDr. Merrill x loebneri Magnolia 'Merrill' Hans Nelson Height: 30’ & Sons Nursery Width: 30’ Zone: 5 Foliage: Medium green leaves are slightly leath- ery. Bloom: Beautiful white, fragrant, star-shaped Magnolia Quick flowers. Bloom Size: 3” Bloom Time: March to April. Reference Guide Bark: Rough, light brown bark with streaks of light grey. Growth Habit: Upright habit, grown as a tree with low branches. MagnoliaAnn Magnolia liliflora 'Ann' Height: 10’ MagnoliaElizabeth acuminata Magnolia x denudata 'Elizabeth' Width: 10’ Height: 35’ Zone: 4 Width: 25’ Foliage: Ovate medium green leaves. Zone: 5 Bloom: Purple-red, chalice-shaped blooms; Foliage: Obovate large green leaves with slightly fragrant. hairs concentrated on the veins. Bloom Size: 4” Bloom: Fragrant creamy-yellow flowers with Bloom time:Mid-April to early May tinges of yellow-green near the base. Bark: Smooth tan or grey bark Bloom Size: 3” Growth Habit: Upright compact, shrubby Bloom Time: March to April before leaves habit; less apt to suffer frost damage in emerge. spring; slow growing. Bark: Smooth grey bark. Growth Habit: Pyramidal habit. MagnoliaBrixton campbellii Belle Magnolia'Brixton Belle' Height: 13’ MagnoliaEmerald virginiana Tower™ 'JN8' Magnolia Width: 11’ Zone: 5 Height: 20’ Foliage: Large oval green leaves. Width: 8’ Bloom: Large rich pink cup and saucer blooms; Zone: 5 flowers are frost resistant. Foliage: Shiny green foliage. Bloom Size: 6” Bloom: Fragrant, creamy-white blooms. Bloom time: Late winter, early spring. Bloom Size: 3” Bark: Beautiful smooth grey bark, similar to Bloom Time: Spring and summer against beech trees. large glossy leaves. Growth Habit: Upright shrub, small tree; often Bark: Smooth grey bark. -

Gardening Without Harmful Invasive Plants

Gardening without harmful invasive plants A guide to plants you can use in place of invasive non-natives Supported by: This guide, produced by the wild plant conservation charity Gardening Plantlife and the Royal Horticultural Society, can help you choose plants that are less likely to cause problems to the environment without should they escape from your garden. Even the most diligent harmful gardener cannot ensure that their plants do not escape over the invasive garden wall (as berries and seeds may be carried away by birds or plants the wind), so we hope you will fi nd this helpful. lslslsls There are laws surrounding invasive enaenaenaena r Rr Rr Rr R non-native plants. Dumping unwanted With over 70,000 plants to choose from and with new varieties being evoevoevoevoee plants, for example in a local stream or introduced each year, it is no wonder we are a nation of gardeners. ©Tr ©Tr ©Tr ©Tr ©Tr ©Tr © woodland, is an offence. Government also However, a few plants can cause you and our environment problems. has powers to ban the sale of invasive These are known as invasive non-native plants. Although they plants. At the time of producing this comprise a small minority of all the plants available to buy for your booklet there were no sales bans, but it An unsuspecting sheep fl ounders in a garden, the impact they can have is extensive and may be irreversible. river. Invasive Floating Pennywort can is worth checking on the websites below Around 60% of the invasive non-native plant species damaging our cause water to appear as solid ground. -

2021 Wholesale Catalog Pinewood Perennial Gardens Table of Contents

2021 Wholesale Catalog Pinewood Perennial Gardens Table of Contents In Our Catalog ........................................................................................................................................2 Quart Program ........................................................................................................................................3 Directions ..............................................................................................................................................3 New Plants for 2021 ...............................................................................................................................4 Native Plants Offered for Sale ..................................................................................................................4 L.I. Gold Medal Plant Program .................................................................................................................5 Characteristics Table ..........................................................................................................................6-10 Descriptions of Plants Achillea to Astilboides .........................................................................................................11-14 Baptisia to Crocosmia ..........................................................................................................14-16 Delosperma to Eupatorium ...................................................................................................16-18 Gaillardia to Helleborus -

Harvard University's Tree Museum: the Legacy and Future of The

29 March 2017 Arboretum Wespelaar Harvard University’s Tree Museum: The Legacy and Future of the Arnold Arboretum Michael Dosmann, Ph.D. Curator of Living Collections President and Fellows of Harvard College, Arnold Arboretum Archives 281 Acres / 114 Hectares The Arnold Arboretum (1872) President and Fellows of Harvard College, Arnold Arboretum Archives Basic to applied biology of woody plants Collection based Fagus grandifolia 1800+ Uses of research in 2016 Research projects per year Practice good horticulture Training and teaching Evaluation, selection, and introduction Tilia cordata Cercidiphyllum japonicum Syringa ‘Purple Haze’ ‘Swedish Upright’ ‘Morioka Weeping’ Publication and Promotion The Backstory – why our trees have value Charles Sprague Sargent Director 1873 - 1927 Arboretum Explorer Accessioned plants 15,441 Total taxa (incl. cultivars) 3,825 Families 104 Genera 357 Species 2,130 Traditional, woody-focused collection Continental climate: -25C to 38C Collection Dynamics There is always change 121-96*C Hamamelis virginiana ‘Mohonk Red’ 1905 150 years later… 2016 Subtraction – ca 300/per year After assessment, removal of low-value material benefits high-value accessions Addition – ca 450/year Adding to the Collections Staking out new Prunus hortulana, from Missouri Planting into the Collections Net Plants – We subtract more than we add, but… when taking into account provenance, Leads to significant change in the permanent collection over time. Provenance Type 2007 2016 Wild 40% 45% Cultivated 41% 38% Uncertain 19% 17% 126-2005*C Betula lenta Plant exploration and The Arnold Arboretum Ernest Henry Wilson expeditions to East Asia • China • 1899-1902 (Veitch) • 1903-1905 (Veitch) • 1907-1909 • 1910-1911 • Japan • 1914 • Japan, Korea, Taiwan • 1917-1919 President and Fellows of Harvard College, Arnold Arboretum Archives Photo by EHW, 7 September 1908, Sichuan Davidia involucrata var. -

Download Article

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, volume 310 3rd International Conference on Culture, Education and Economic Development of Modern Society (ICCESE 2019) Research on the Inheritance and Development of Sichuan Qingyin* Ya Zhang College of Music Sichuan Normal University Chengdu, China Abstract—Taking the inheritance of Sichuan Qingyin as the research object, this paper explores how to inherit and carry II. THE CHANGE OF INHERITANCE WAY forward Sichuan Qingyin in today's society through the analysis Since the Qing Dynasty, Sichuan Qingyin has undergone of its inheritance mode, purpose, change of songs and change of many social changes, such as the 1911 Revolution, the May audience groups. 4th Movement and the War of Resistance against Japan. Some amateurs started full time to make ends meet. They either took Keywords—Sichuan Qingyin; contemporary environment; cultural inheritance a family as a team, or combine freely as a team, or "adopting girls" wandering in major cities and towns, known as "family group" and "nest group". At first, apprentices came to master I. INTRODUCTION to learn art. Masters used the method of oral and heart-to-heart Sichuan Qingyin prevailed during the reign of Qianlong in teaching. Masters taught and sang one phase orally, and the Qing Dynasty. It centered on Luzhou and Xufu, and spread apprentices imitated and sang one phase along. Although this all over towns and villages. Originally known as pipa singing way of inheritance is primitive, the master could teach and yueqin singing, it is a traditional form of music in Sichuan. apprentices personally. The apprentice could master the It has both the name of elegance and the meaning of Qingyin. -

The Progressive and Ancestral Traits of the Secondary Xylem Within Magnolia Clad – the Early Diverging Lineage of Flowering Plants

Acta Societatis Botanicorum Poloniae ORIGINAL RESEARCH PAPER Acta Soc Bot Pol 84(1):87–96 DOI: 10.5586/asbp.2014.028 Received: 2014-07-31 Accepted: 2014-12-01 Published electronically: 2015-01-07 The progressive and ancestral traits of the secondary xylem within Magnolia clad – the early diverging lineage of flowering plants Magdalena Marta Wróblewska* Department of Developmental Plant Biology, Institute of Experimental Biology, University of Wrocław, Kanonia 6/8, 50-328 Wrocław, Poland Abstract The qualitative and quantitative studies, presented in this article, on wood anatomy of various species belonging to ancient Magnolia genus reveal new aspects of phylogenetic relationships between the species and show evolutionary trends, known to increase fitness of conductive tissues in angiosperms. They also provide new examples of phenotypic plasticity in plants. The type of perforation plate in vessel members is one of the most relevant features for taxonomic studies. InMagnolia , until now, two types of perforation plates have been reported: the conservative, scalariform and the specialized, simple one. In this paper, are presented some findings, new to magnolia wood science, like exclusively simple perforation plates in some species or mixed perforation plates – simple and scalariform in one vessel member. Intravascular pitting is another taxonomically important trait of vascular tissue. Interesting transient states between different patterns of pitting in one cell only have been found. This proves great flexibility of mechanisms, which elaborate cell wall structure in maturing trache- ary element. The comparison of this data with phylogenetic trees, based on the fossil records and plastid gene expression, clearly shows that there is a link between the type of perforation plate and the degree of evolutionary specialization within Magnolia genus.