The Kapralova Society Journal Summer 2020

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thomas D. Svatos and Twentieth-Century Czech Critical Culture

ex tempore A Journal of Compositional and Theoretical Research in Music Vol. XIV/2, Spring / Summer 2009 _________________________ A Clash over Julietta: the Martinů/Nejedlý Political Conflict - Thomas D. Svatos and Twentieth-Century Czech Critical Culture Dialectic in Miniature: Arnold Schoenberg‟s - Matthew Greenbaum Sechs Kleine Klavierstücke Opus 19 Stravinsky's Bayka (1915-16): Prose or Poetry? - Marina Lupishko Pitch Structures in Reginald Smith Brindle’s -Sundar Subramanian El Polifemo de Oro Rhythmic Cells and Organic Development: - Jean-Louis Leleu The Function of Harmonic Fields in Movement IIIb of Livre pour quatuor by Pierre Boulez Analytical Diptych: Boulez Anthèmes / Berio Sequenza XI - John MacKay co-editors: George Arasimowicz, California State University, Dominguez Hills John MacKay, West Springfield, MA associate editors: Per Broman, Bowling Green University Jeffrey Brukman, Rhodes University, RSA John Cole, Elisabeth University of Music, JAP Angela Ida de Benedictis, University of Pavia, IT Paolo Dal Molin, Université Paul Verlaine de Metz, FR Alfred Fisher, Queen‟s University, CAN Cynthia Folio, Temple University Gerry Gabel, Texas Christian University Tomas Henriques, Universidade Nova de Lisboa, POR Timothy Johnson, Ithaca College David Lidov, York University, CAN Marina Lupishko, le Havre, FRA Eva Mantzourani, Canterbury Christchurch Univ, UK Christoph Neidhöfer, McGill University, CAN Paul Paccione, Western Illinois University Robert Rollin, Youngstown State University Roger Savage, UCLA Stuart Smith, University of Maryland Thomas Svatos, Eastern Mediterranean Univ, TRNC André Villeneuve UQAM, CAN Svatos/A Clash over Julietta 1 A Clash over Julietta: The Martinů/Nejedlý Political Conflict and Twentieth-Century Czech Critical Culture Thomas D. Svatos We know and honor our Smetana, but that he must have been a Bolshevik, this is a bit out of hand. -

Interpreting Tempo and Rubato in Chopin's Music

Interpreting tempo and rubato in Chopin’s music: A matter of tradition or individual style? Li-San Ting A thesis in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of New South Wales School of the Arts and Media Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences June 2013 ABSTRACT The main goal of this thesis is to gain a greater understanding of Chopin performance and interpretation, particularly in relation to tempo and rubato. This thesis is a comparative study between pianists who are associated with the Chopin tradition, primarily the Polish pianists of the early twentieth century, along with French pianists who are connected to Chopin via pedagogical lineage, and several modern pianists playing on period instruments. Through a detailed analysis of tempo and rubato in selected recordings, this thesis will explore the notions of tradition and individuality in Chopin playing, based on principles of pianism and pedagogy that emerge in Chopin’s writings, his composition, and his students’ accounts. Many pianists and teachers assume that a tradition in playing Chopin exists but the basis for this notion is often not made clear. Certain pianists are considered part of the Chopin tradition because of their indirect pedagogical connection to Chopin. I will investigate claims about tradition in Chopin playing in relation to tempo and rubato and highlight similarities and differences in the playing of pianists of the same or different nationality, pedagogical line or era. I will reveal how the literature on Chopin’s principles regarding tempo and rubato relates to any common or unique traits found in selected recordings. -

Our Newly Designed Website We Are Happy to Announce That the Twin Cities Opera Guild Has a New Website That Can Now Be Accessed on Your Phone

Celebrating 69 Years of Opera Education for Children Summer 2021 Newsletter 2021 Spring Benefit to Fund Music Education for Children Enjoy A Virtual Celebration – A Video from Fargo Moorhead Opera Young Artists August 24, 2021 Interlachen Country Club • Edina Featuring Alyssa Anderson, Mezzo Soprano Justin Spenner, Baritone Julian Ward, Pianist Our Newly Designed Website We are happy to announce that the Twin Cities Opera Guild has a new website that can now be accessed on your phone. Check us out at: www.twincitiesoperaguild.org on your computer or phone Letter from the President of TCOG It looks like we made it! We are Country Club and the delicious miso sea bass, so we at the end of the tunnel, and it are holding our fun Party in Pink, with sea bass, at looks bright and sunny. All of us Interlachen on August 24. I am so looking forward to suffered in many ways – illness, hearing opera in person again! Details are elsewhere grief, loneliness. Getting my in this newsletter. I hope everyone can come! Our Big Welcome Back Party vaccine in February was the best This is my last letter as President. I have enjoyed thing imaginable, I could reenter meeting you all, our events, and projects. Twin Cities the world. Opera Guild is in fine shape, and our new President, TCOG decided to wait a bit before resuming our Kathryn Keefer, has a long history with TCOG and events, to give folks time to get vaccinated and adjust will do a wonderful job. I hope to see you all at our to the new maskless world. -

The Bach Variations: a Philharmonic Festival March 6–April 6, 2013

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE February 20, 2013 Contact: Katherine E. Johnson (212) 875-5718; [email protected] THE BACH VARIATIONS: A PHILHARMONIC FESTIVAL MARCH 6–APRIL 6, 2013 PROGRAM II OF IV Alan Gilbert To Conduct Mass in B minor With Soprano Dorothea Röschmann, Mezzo-Soprano Anne Sofie von Otter, Tenor Steve Davislim, and Bass-Baritone Eric Owens with the New York Choral Artists March 13–16 The New York Philharmonic will present The Bach Variations: A Philharmonic Festival March 6–April 6, 2013. On the festival’s second orchestral program, Alan Gilbert will conduct the Philharmonic in Bach’s Mass in B minor, with soprano Dorothea Röschmann, mezzo-soprano Anne Sofie von Otter, tenor Steve Davislim, bass-baritone Eric Owens, and the New York Choral Artists, Joseph Flummerfelt, director, Wednesday, March 13, 2013, at 7:30 p.m.; Thursday, March 14 at 7:30 p.m.; Friday, March 15 at 8:00 p.m.; and Saturday, March 16 at 8:00 p.m. “The Mass in B minor is a consummate masterpiece that makes me feel humble as a musician when I hear it,” Alan Gilbert said. “Bach took a liturgical, religious starting point and made it even more universal. No matter what you believe, no matter your religious credo, or whether or not you even have a religious credo, it is impossible not to be incredibly moved by this music because it speaks from one human being directly into the heart of another. I feel very privileged to be able to touch this music.” The Bach Variations marks the first time the New York Philharmonic has presented a festival of the music of the Baroque master. -

A Survey of Czech Piano Cycles: from Nationalism to Modernism (1877-1930)

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: A SURVEY OF CZECH PIANO CYCLES: FROM NATIONALISM TO MODERNISM (1877-1930) Florence Ahn, Doctor of Musical Arts, 2018 Dissertation directed by: Professor Larissa Dedova Piano Department The piano music of the Bohemian lands from the Romantic era to post World War I has been largely neglected by pianists and is not frequently heard in public performances. However, given an opportunity, one gains insight into the unique sound of the Czech piano repertoire and its contributions to the Western tradition of piano music. Nationalist Czech composers were inspired by the Bohemian landscape, folklore and historical events, and brought their sentiments to life in their symphonies, operas and chamber works, but little is known about the history of Czech piano literature. The purpose of this project is to demonstrate the unique sentimentality, sensuality and expression in the piano literature of Czech composers whose style can be traced from the solo piano cycles of Bedřich Smetana (1824-1884), Antonín Dvořák (1841-1904), Leoš Janáček (1854-1928), Josef Suk (1874-1935), Bohuslav Martinů (1890-1935) to Erwin Schulhoff (1894-1942). A SURVEY OF CZECH PIANO CYCLES: FROM ROMANTICISM TO MODERNISM (1877-1930) by Florence Ahn Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Maryland, College Park, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts 2018 Advisory Committee: Professor Larissa Dedova, Chair Professor Bradford Gowen Professor Donald Manildi Professor -

General Index

Cambridge University Press 0521780098 - The Cambridge Companion to Twentieth-Century Opera Edited by Mervyn Cooke Index More information General index Abbate, Carolyn 282 Bach, Johann Sebastian 105 Adam, Fra Salimbene de 36 Bachelet, Alfred 137 Adami, Giuseppe 36 Baden-Baden 133 Adamo, Mark 204 Bahr, Herrmann 150 Adams, John 55, 204, 246, 260–4, 289–90, Baird, Tadeusz 176 318, 330 Bala´zs, Be´la 67–8, 271 Ade`s, Thomas 228 ballad opera 107 Adlington, Robert 218, 219 Baragwanath, Nicholas 102 Adorno, Theodor 20, 80, 86, 90, 95, 105, 114, Barbaja, Domenico 308 122, 163, 231, 248, 269, 281 Barber, Samuel 57, 206, 331 Aeschylus 22, 52, 163 Barlach, Ernst 159 Albeniz, Isaac 127 Barry, Gerald 285 Aldeburgh Festival 213, 218 Barto´k, Be´la 67–72, 74, 168 Alfano, Franco 34, 139 The Wooden Prince 68 alienation technique: see Verfremdungse¤ekt Baudelaire, Charles 62, 64 Anderson, Laurie 207 Baylis, Lilian 326 Anderson, Marian 310 Bayreuth 14, 18, 21, 49, 61–2, 63, 125, 140, 212, Andriessen, Louis 233, 234–5 312, 316, 335, 337, 338 Matthew Passion 234 Bazin, Andre´ 271 Orpheus 234 Beaumarchais, Pierre-Augustin Angerer, Paul 285 Caron de 134 Annesley, Charles 322 Nozze di Figaro, Le 134 Ansermet, Ernest 80 Beck, Julian 244 Antheil, George 202–3 Beckett, Samuel 144 ‘anti-opera’ 182–6, 195, 241, 255, 257 Krapp’s Last Tape 144 Antoine, Andre´ 81 Play 245 Apollinaire, Guillaume 113, 141 Beeson, Jack 204, 206 Appia, Adolphe 22, 62, 336 Beethoven, Ludwig van 87, 96 Aquila, Serafino dall’ 41 Eroica Symphony 178 Aragon, Louis 250 Beineix, Jean-Jacques 282 Argento, Dominick 204, 207 Bekker, Paul 109 Aristotle 226 Bel Geddes, Norman 202 Arnold, Malcolm 285 Belcari, Feo 42 Artaud, Antonin 246, 251, 255 Bellini, Vincenzo 27–8, 107 Ashby, Arved 96 Benco, Silvio 33–4 Astaire, Adele 296, 299 Benda, Georg 90 Astaire, Fred 296 Benelli, Sem 35, 36 Astruc, Gabriel 125 Benjamin, Arthur 285 Auden, W. -

From Piano Girl to Professional: the Changing

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--Music Music 2014 FROM PIANO GIRL TO PROFESSIONAL: THE CHANGING FORM OF MUSIC INSTRUCTION AT THE NASHVILLE FEMALE ACADEMY, WARD’S SEMINARY FOR YOUNG LADIES, AND THE WARD- BELMONT SCHOOL, 1816-1920 Erica J. Rumbley University of Kentucky, [email protected] Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Rumbley, Erica J., "FROM PIANO GIRL TO PROFESSIONAL: THE CHANGING FORM OF MUSIC INSTRUCTION AT THE NASHVILLE FEMALE ACADEMY, WARD’S SEMINARY FOR YOUNG LADIES, AND THE WARD-BELMONT SCHOOL, 1816-1920" (2014). Theses and Dissertations--Music. 24. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/music_etds/24 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Music at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--Music by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained needed written permission statement(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine) which will be submitted to UKnowledge as Additional File. I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the irrevocable, non-exclusive, and royalty-free license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. -

BMN 2002/2.Indd

Bohuslav Martinů May – August 2002 Always Slightly off Center An Interview with Christopher Hogwood When the Fairies Learned to Walk Feuilleton on The Three Wishes in Augsburg Second The Wonderful Flights issue It Was a Dream for Me to Have a Piece by Martinů Jiří Tancibudek and Concerto for Oboe and Small Orchestra 25 Years of the Martinů Quartet Bats in the Belfry The Film Victims and Murderers Martinů News and Events The International Bohuslav Martinů Society The Bohuslav Martinů Institute CONTENTS WELCOME Karel Van Eycken ....................................... 3 BOHUSLAV MARTINŮ SOCIETIES AROUND THE WORLD .................................. 3 ALWAYS SLIGHTLY OFF CENTER Christopher Hogwood interviewed by Aleš Březina ..................................... 4 - 6 REVIEW Sandra Bergmannová ................................. 7 WHEN THE FAIRIES LEARNED TO WALK Feuilleton on The Three Wishes in Augsburg Jörn Peter Hiekel .......................................8 BATS IN THE BELFRY The Film Victims and Murderers Patrick Lambert ........................................ 9 MARTINŮ EVENTS 2002 ........................10 - 11 THE WONDERFUL FLIGHTS Gregory Terian .........................................12 THE CZECH RHAPSODY IN A NEW GARB Adam Klemens .........................................13 25 YEARS OF THE MARTINŮ QUARTET Eva Vítová, Jana Honzíková ........................14 “MARTINŮ WAS A GREAT MUSICIAN, UNFORGETTABLE…” Announcement about Margrit Weber ............15 IT WAS A DREAM FOR ME TO HAVE A PIECE BY MARTINŮ Jiří Tancibudek and Concerto -

Cinq Études De Jazz

CINQ ÉTUDES DE JAZZ: A STUDY OF JAZZ AND MODERNISM by JEREMEY JAMES MCMILLAN KEVIN THOMAS CHANCE, COMMITTEE CHAIR EDISHER SAVITSKI THOMAS S. ROBINSON JOSEPH SARGENT JACOB W. ADAMS WILLIAM A. MARTIN A DOCUMENT Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in the Department of Music in the Graduate School of The University of Alabama TUSCALOOSA, ALABAMA 2019 Copyright 2019 Jeremey McMillan ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT When Erwin Schulhoff’s Cinq Études de Jazz appeared in 1926, the major cities in the United States and Europe were witnessing a global jazz phenomenon. Paris was among the major cities and cultural centers where the spirit of jazz ventured beyond the dance hall. Although the French reception of jazz has been thoroughly documented, this study offers a unique vantage point through a close musical analysis of this work. Schulhoff was a Czech composer who used his vantage point as an outsider to witness the influence of jazz on French culture and modern art. Besides the musical analysis, this study treats Schulhoff’s Cinq Études as a documentary by examining the unfolding of developments in the arts during the seventy-year period that preceded the 1920s. By examining the concurrent emergence of the European avant-garde and jazz, along with their similar ethos as a reaction to the sociopolitical climate of the time, this document seeks to implore the reader to consider that jazz—not simply a mere influence to modernism—is itself a branch of modern art. ii DEDICATION This document is dedicated to the memory of my father, Jerry Charles McMillan (1947- 2010). -

Neeme Järvi Bohuslav Martinů, at Home in Vieux-Moulin, France, 1937 Lebrecht Music & Arts Photo Library / © Památník Bohuslava Martinů Bohuslav Martinů (1890 – 1959)

ˆ ˆ Suites from ‘Spalícek’ Rhapsody-Concerto Mikhail Zemtsov viola Estonian National Symphony Orchestra Neeme Järvi © Památník Bohuslava Martinů / Lebrecht Music & Arts Photo Library Bohuslav Martinů,athomein Bohuslav Vieux-Moulin, France, 1937 France, Vieux-Moulin, Bohuslav Martinů (1890 – 1959) Suites from Špalíček’, H 214 (1931 – 32, revised 1937, 1940) (Chapbook) Opera-ballet in Three Acts Liidia Ilves piano Suite No. 1, H 214A* 22:29 1 I Prelude (Předehra). Poco allegro 1:22 2 II Dance with the Hare (Tanec se zajícem). Allegretto poco moderato 1:31 III In the Magician’s Palace (V paláci černokněžníkově) 3 Dance of the Shadows (Tanec stínů). Moderato – Poco allegro – Allegro – 2:18 4 Dance of the Lion (Tanec lva). Moderato – 1:15 5 Dance of the Sparrow-hawk (Tanec krahujce). Allegro vivo – 0:37 6 Dane of the Little Mouse (Tanec malé myšky). Allegretto – Poco vivo – 1:19 7 Change of Scene and Dance of Puss in Boots (Proměna a tanec Kocoura v botách). Lento – Allegretto – Poco vivo 1:42 8 IV Cinderella’s Ball at the Palace (Popelčin ples na zámku). Lento – Moderato – Allegro moderato – Poco vivo – Tempo I 9:32 9 V The Wedding Polka (Svatební Polka). Moderato – Poco vivo – Meno – Allegro – Poco vivo – Più vivo – Allegro vivo 2:33 3 Suite No. 2, H 214B* 22:24 10 I Dance of the Devils (Tanec čertů). Allegro 2:55 11 II The Shoemaker’s Capricious Patron (Ševcova rozmarná zákaznice). Poco vivo 1:22 12 III The Market – Dance of the Bumble-bee (Trh – Tanec čmeláka). Moderato – Moderato (Un poco più vivo) 3:01 IV The Rescue of the Princess (Vysvobození princeznino) 13 1. -

Do 5. Dez 2019

DO 5. DEZ 2019 JERUSALEM QUARTET HILA BAGGIO 3. KAMMERKONZERT / BEGINN: 20.00 UHR HAUS DER MUSIK INNSBRUCK, GROSSER SAAL PROGRAMM MEISTER& KAMMERKONZERTE INNSBRUCK ERWIN SCHULHOFF (1894–1942) Fünf Stücke für Streichquartett (1923) I Alla Valse viennese. Allegro II Alla Serenata. Allegretto con moto III Alla Czeca. Molto allegro IV Alla Tango milonga. Andante V Alla Tarantella. Prestissimo con fuoco JERUSALEM QUARTET LEONID DESYATNIKOV (*1955) ALEXANDER PAVLOVSKY Jiddisch – 5 Lieder für Stimme VIOLINE und Streichquartett (2018) SERGEI BRESLER – Angeregt vom Jerusalem Quartet – VIOLINE I Varshe ORI KAM II In a hoyz vu men veynt un men lakht VIOLA III Ikh ganve in der nakht IV Yosl un Sore-Dvoshe KYRIL ZLOTNIKOV V Ikh vel shoyn mer nit ganvenen VIOLONCELLO – PAUSE – HILA BAGGIO ERICH WOLFGANG KORNGOLD (1897–1957 ) SOPRAN Streichquartett Nr. 2 Es-Dur op. 26 (1933) I Allegro II Intermezzo. Allegretto con moto – Molto più mosso – Tempo primo III Larghetto. Lento – Con molto sentimento IV Waltz (Finale). Tempo di Valse – Grandioso – Più mosso Einführungsgespräch: 19.00 Uhr im Großen Saal 2 3 NOTIZEN MEISTER& KAMMERKONZERTE INNSBRUCK TANZPHANTASIEN Musiker mit sozialistischen Ideen. Schulhoff sah sich nach der Okkupation der Tschechischen Republik und der Slowakei 1938/39 durch die Deutschen doppelt gefährdet: Erwin Schulhoff starb 1942 im als Jude und als Kommunist. Nach dem Hitler-Stalin-Pakt Nazi-Internierungslager Wülzburg beantragte er die russische Staatsbürgerschaft, da er sich an den Folgen einer Tuberkulose. als sowjetischer Staatsangehöriger vor der Verfolgung aus Die Musikwelt verlor mit ihm einen Rassengründen sicher wähnte. Doch nur einen Tag nach profilierten Komponisten und exzel- dem Angriff Deutschlands auf die Sowjet union wurde lenten Pianisten, der entscheidend Schulhoff mit seiner Familie von der „Ausländer polizei“ in an den Entwicklungen der musikali- Brünn aufgegriffen und deportiert. -

TOC 0249 CD Booklet.Indd

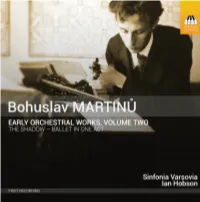

BOHUSLAV MARTINŮ: EARLY ORCHESTRAL WORKS, VOLUME TWO by Michael Crump In 1906 a promising young Czech violinist called Bohuslav Martinů lef his home town of Polička and began life as a student at the Conservatoire in Prague. His studies were made possible largely afer an appeal in his local newspaper raised the necessary funds. Doubtless he had every intention of rewarding the trust thus placed in him by graduating with full honours, but the cultural life of the Czech capital proved to be irresistibly distracting. Te performances at the National Teatre, in particular, drew him like a magnet night afer night, usually in the company of his friend and fellow-student Stanislav Novák. His devotion to the theatre unfortunately led to the neglect of his violin studies and his eventual expulsion from the Conservatoire in 1910, but by this time he was already well aware that his future lay in composition, not performance. He stayed on in Prague, supported by modest fnancial support from his parents, and his love-afair with the National Teatre continued unabated. Novák later wrote a short reminiscence of his friend, giving details of his musical sympathies at this time of his life: He was free, nobody bothered him with counterpoint, he could attend rehearsals of the Philharmonic and read all day, he could compose whatever and however he liked and in the evening he would have to get himself to the theatre at any price. At this time he would never miss a single performance of Smetana’s operas, nor of Rusalka or Te Jacobin.