From Piano Girl to Professional: the Changing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Women's Suffrage in Tennessee

Are you Yellow or Red? Women’s Suffrage in Tennessee Lesson plans for primary sources at the Tennessee State Library & Archives Author: Whitney Joyner, Northeast Middle School Grade Level: 11th grade Date Created: May 2015 Visit www.tn.gov/tsla/educationoutreach for additional lesson plans. Introduction: The ratification of the 19th amendment was the pinnacle of the Progressive Move- ment and Tennessee played a pivotal role in gaining women the right to vote in the United States. In Au- gust 1920, Tennessee became the 36th state to ratify the 19th amendment and changed American poli- tics forever. Guiding Questions: What were the key arguments for and against women’s suffrage? Who were the key players in the fight for and against women’s suffrage? What role did Tennessee plan in the suffrage effort? Learning Objectives: In the course of the lesson, students will, explore the ideas for and against women gaining the right to vote, identify the leaders of the women’s suffrage movement , and define Tennessee’s role in the women’s suffrage movement. Curriculum Standards: US.18- Describe the movement to achieve suffrage for women, including: the significance of leaders such as Carrie Chapman Catt, Anne Dallas Dudley, and Alice Paul, the activities of suffragists, the passage of the 19th Amendment, and the role of Tennessee as the “Perfect 36”). (C, E, G, H, P) CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RH.11-12.1 Cite specific textual evidence to support analysis of primary and secondary sources, connecting insights gained from specific details to an understanding of the text as a whole. -

Interpreting Tempo and Rubato in Chopin's Music

Interpreting tempo and rubato in Chopin’s music: A matter of tradition or individual style? Li-San Ting A thesis in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of New South Wales School of the Arts and Media Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences June 2013 ABSTRACT The main goal of this thesis is to gain a greater understanding of Chopin performance and interpretation, particularly in relation to tempo and rubato. This thesis is a comparative study between pianists who are associated with the Chopin tradition, primarily the Polish pianists of the early twentieth century, along with French pianists who are connected to Chopin via pedagogical lineage, and several modern pianists playing on period instruments. Through a detailed analysis of tempo and rubato in selected recordings, this thesis will explore the notions of tradition and individuality in Chopin playing, based on principles of pianism and pedagogy that emerge in Chopin’s writings, his composition, and his students’ accounts. Many pianists and teachers assume that a tradition in playing Chopin exists but the basis for this notion is often not made clear. Certain pianists are considered part of the Chopin tradition because of their indirect pedagogical connection to Chopin. I will investigate claims about tradition in Chopin playing in relation to tempo and rubato and highlight similarities and differences in the playing of pianists of the same or different nationality, pedagogical line or era. I will reveal how the literature on Chopin’s principles regarding tempo and rubato relates to any common or unique traits found in selected recordings. -

CHALENE HELMUTH Senior Lecturer Department of Spanish And

CHALENE HELMUTH Senior Lecturer Department of Spanish and Portuguese Faculty Head of Sutherland House The Martha Rivers Ingram Commons Peabody #560 230 Appleton Place Vanderbilt University [email protected] EDUCATION Ph.D., Spanish American Literature, University of Kentucky, 1991 M.A., Spanish, University of Kentucky, 1988 B.A., Spanish, Asbury College, 1986 Elementary and Secondary Education, San José, Costa Rica TEACHING Vanderbilt University Senior Lecturer (Fall 2003-present) SPAN 1001 iSeminar: Strategies for Successful Study Abroad iSeminar: Eco-Conscious Travel SPAN 1100 Spanish for True Beginners SPAN 1101/1102 Elementary Spanish I and II SPAN 1101G Spanish for Reading SPAN 1103 Intensive Elementary Spanish SPAN 1103 Eco-critical Perspectives in Latin American Literature SPAN 3301W Intermediate Spanish Writing SPAN 3202 Spanish for Oral Communication SPAN 3303 Introduction to Hispanic Literature SPAN 3340 Advanced Spanish Conversation SPAN 4425 Spanish American Literature from 1900 to the Present SPAN 4740 Spanish-American Literature of the Boom Era SPAN 4948 Senior Honors Thesis Faculty Director, Vanderbilt Initiative in Scholarship and Global Engagement (VISAGE) Costa Rica, 2008-2013 INDS 3831 Seminar in Global Citizenship, Service, and Research: Ecotourism, Civic Engagement, and Corporate Social Responsibility Faculty Director, Vanderbilt/Tulane in Costa Rica, 2014-2016 SPAN 3893 Reading Green: Engaging the Environment in Spanish American Literature Helmuth 2 Middlebury College Undergraduate Faculty, Spanish Language -

June 1902) Winton J

Gardner-Webb University Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 John R. Dover Memorial Library 6-1-1902 Volume 20, Number 06 (June 1902) Winton J. Baltzell Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude Part of the Composition Commons, Ethnomusicology Commons, Fine Arts Commons, History Commons, Liturgy and Worship Commons, Music Education Commons, Musicology Commons, Music Pedagogy Commons, Music Performance Commons, Music Practice Commons, and the Music Theory Commons Recommended Citation Baltzell, Winton J.. "Volume 20, Number 06 (June 1902)." , (1902). https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude/471 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the John R. Dover Memorial Library at Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. It has been accepted for inclusion in The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE PUBLISHER OF THE ETVDE WILL SUPPLY ANYTHING IN MUSIC. 11^ VPl\W4-»* _ The Sw»d Volume ol ••The Cmet In Mmk" mil be rmdy to «'»!' >* Apnl "* WORK m VOLUME .. 5KI55 nETUDE I, Clic.pl". Oodard. and Sohytte. II. Chamlnade. J^ ^ Sthumann and Mosz- Q. Smith. A. M. Foerater. and Oeo. W. W|enin«ki. VI. kowski (Schumann occupies 75 pages). • Kelley» Wm. Berger, and Deahm. and Fd. Sehnett. VII. It. W. O. B. Klein. VIII, Saint-Saens, Paderewski, Q Y Bn|ch Max yogrich. IX. (llazounov, Balakirev, the Waltz Strau ’ M g Forces in the X. Review ol the Coum a. a Wholes The Place ol Bach nr Development; Influence ol the Folks Song, etc. -

Women's Suffrage Centennial Commemorative Coin

G:\COMP\116\WOMEN’S SUFFRAGE CENTENNIAL COMMEMORATIVE COI....XML Women’s Suffrage Centennial Commemorative Coin Act [Public Law 116–71] [This law has not been amended] øCurrency: This publication is a compilation of the text of Public Law 116–71. It was last amended by the public law listed in the As Amended Through note above and below at the bottom of each page of the pdf version and reflects current law through the date of the enactment of the public law listed at https:// www.govinfo.gov/app/collection/comps/¿ øNote: While this publication does not represent an official version of any Federal statute, substantial efforts have been made to ensure the accuracy of its contents. The official version of Federal law is found in the United States Statutes at Large and in the United States Code. The legal effect to be given to the Statutes at Large and the United States Code is established by statute (1 U.S.C. 112, 204).¿ AN ACT To require the Secretary of the Treasury to mint coins in commemoration of ratification of the 19th Amendment to the Constitution of the United States, giving women in the United States the right to vote. Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled, SECTION 1. ø31 U.S.C. 5112 note¿ SHORT TITLE. This Act may be cited as the ‘‘Women’s Suffrage Centennial Commemorative Coin Act’’. SEC. 2. FINDINGS; PURPOSE. (a) FINDINGS.—Congress finds the following: (1) Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Lucretia Mott organized the first Women’s Rights Convention in Seneca Falls, New York. -

Maud Powell As an Advocate for Violinists, Women, and American Music Catherine C

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2012 "The Solution Lies with the American Women": Maud Powell as an Advocate for Violinists, Women, and American Music Catherine C. Williams Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC “THE SOLUTION LIES WITH THE AMERICAN WOMEN”: MAUD POWELL AS AN ADVOCATE FOR VIOLINISTS, WOMEN, AND AMERICAN MUSIC By CATHERINE C. WILLIAMS A Thesis submitted to the College of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Music Degree Awarded: Summer Semester, 2012 Catherine C. Williams defended this thesis on May 9th, 2012. The members of the supervisory committee were: Denise Von Glahn Professor Directing Thesis Michael Broyles Committee Member Douglass Seaton Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the thesis has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii For Maud iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank my parents and my brother, Mary Ann, Geoff, and Grant, for their unceasing support and endless love. My entire family deserves recognition, for giving encouragement, assistance, and comic relief when I needed it most. I am in great debt to Tristan, who provided comfort, strength, physics references, and a bottomless coffee mug. I would be remiss to exclude my colleagues in the musicology program here at The Florida State University. The environment we have created is incomparable. To Matt DelCiampo, Lindsey Macchiarella, and Heather Paudler: thank you for your reassurance, understanding, and great friendship. -

Kindergarten the World Around Us

Kindergarten The World Around Us Course Description: Kindergarten students will build upon experiences in their families, schools, and communities as an introduction to social studies. Students will explore different traditions, customs, and cultures within their families, schools, and communities. They will identify basic needs and describe the ways families produce, consume, and exchange goods and services in their communities. Students will also demonstrate an understanding of the concept of location by using terms that communicate relative location. They will also be able to show where locations are on a globe. Students will describe events in the past and in the present and begin to recognize that things change over time. They will understand that history describes events and people of other times and places. Students will be able to identify important holidays, symbols, and individuals associated with Tennessee and the United States and why they are significant. The classroom will serve as a model of society where decisions are made with a sense of individual responsibility and respect for the rules by which they live. Students will build upon this understanding by reading stories that describe courage, respect, and responsible behavior. Culture K.1 DHVFULEHIDPLOLDUSHRSOHSODFHVWKLQJVDQGHYHQWVZLWKFODULI\LQJGHWDLODERXWDVWXGHQW¶V home, school, and community. K.2 Summarize people and places referenced in picture books, stories, and real-life situations with supporting detail. K.3 Compare family traditions and customs among different cultures. K.4 Use diagrams to show similarities and differences in food, clothes, homes, games, and families in different cultures. Economics K.5 Distinguish between wants and needs. K.6 Identify and explain how the basic human needs of food, clothing, shelter and transportation are met. -

FC 11.1 Fall1989.Pdf (1.705Mb)

WOMEN'SSTUDIES LIBRARIAP The University of Wisconsin System - FEMINIST- OLLECTIONS CA QUARTERLYOF WOMEN'S STUDIES RESOURCES TABLE OF CONTENTS FROM THE EDITORS.. ..........................................3 BOOKREVIEWS ................................................. Looking at the Female Spectator, by Julie D'Acci. Middle Eastern and Islamic Women 'Talk Back," by Sondra Hale. FEMINISTVISIONS .............................................10 Four Black American Musicians, by Jane Bowers. THE CAIRNS COLLECTION OF AMERICAN WOMEN WRITERS.. 12 By Yvonne Schofer. WOMEN OF COLOR AND THE CORE CURRICULUM.. ...........15 Tools for Transforming the Liberal Arts: Part 1, By Susan Searing. ARCHIVES .....................................................l 8 Women & Media Collection; and a microfilm project on Bay area gay and lesbian periodicals. FEMINIST PUBLISHING .........................................18 Two new presses. Continued on next page Feminist Collections Page 2 Table of Contents Continued NEW REFERENCE WORKS IN WOMEN'S STUDIES.. ............ .19 Bibliographies on African women, women's diaries and letters, educational equity resources, Gertrude Stein, Third World women's education, women mystery writers, and British women writers, plus a biographical dictionary and a guide for getting published in women's studies. PERIODICAL NOTES. .......................................... .23 New periodicals on Latin American women in Canada and abroad, new women's fiction, feminist cultural studies, gender in historical perspective, feminist humor, women -

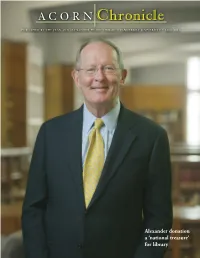

ACORN Chronicle

ACORN Chronicle PUBLISHED BY THE JEAN AND ALEXANDER HEARD LIBRARY • VANDERBILT UNIVERSITY • F ALL 2011 Alexander donation a ‘national treasure’ for library Special Collections welcomes Sen. Alexander’s donation of papers V A N D ne of Vanderbilt’s most well- E R B I L T known graduates, U.S. Sen. U N I V E Lamar Alexander (BA’62) and R S I T Y O S his wife, Honey Alexander, have made one P E C I A L of the most important donations in the C O L L Jean and Alexander Heard Library’s histo - E C T I O N ry by giving their pre-Senate papers to S Special Collections. The collection contains a wealth of his - torical documents from Alexander’s political campaigns, his two terms as governor, Honey Alexander’s roles as wife, mother, first lady and advocate for family causes, along with the senator’s correspondence with close friend and author Alex Haley. Papers from Alexander’s tenure as president of the University of Tennessee and U.S. sec - retary of education are also included. “Honey and I felt that the archives (above) Nissan CEO Marvin Runyon and Lamar Alexander shake hands as the first Sentra rolls should reflect the voices of the countless off the production line in March 1985. Alexander was instrumental in drawing both Japanese Tennesseans who have worked with us to manufacturing and the auto industry to Tennessee. (top of page) As Tennessee’s governor, Lamar raise educational standards, attract indus - Alexander addresses the crowd at his inauguration in January 1983. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season

INFANTRY HALL PROVIDENCE >©§to! Thirty-fifth Season, 1915-1916 Dr. KARL MUCK, Conductor WITH HISTORICAL AND DESCRIPTIVE NOTES BY PHILIP HALE TUESDAY EVENING, DECEMBER 28 AT 8.15 COPYRIGHT, 1915, BY C. A. ELLIS PUBLISHED BY C. A. ELLIS. MANAGER ii^^i^"""" u Yes, Ifs a Steinway" ISN'T there supreme satisfaction in being able to say that of the piano in your home? Would you have the same feeling about any other piano? " It's a Steinway." Nothing more need be said. Everybody knows you have chosen wisely; you have given to your home the very best that money can buy. You will never even think of changing this piano for any other. As the years go by the words "It's a Steinway" will mean more and more to you, and thousands of times, as you continue to enjoy through life the com- panionship of that noble instrument, absolutely without a peer, you will say to yourself: "How glad I am I paid the few extr? dollars and got a Steinway." STEINWAY HALL 107-109 East 14th Street, New York Subway Express Station at the Door Represented by the Foremost Dealers Everywhere 2>ympif Thirty-fifth Season,Se 1915-1916 Dr. KARL MUC per; \l iCs\l\-A Violins. Witek, A. Roth, 0. Hoffmann, J. Rissland, K. Concert-master. Koessler, M. Schmidt, E. Theodorowicz, J. Noack, S. Mahn, F. Bak, A. Traupe, W. Goldstein, H. Tak, E. Ribarsch, A. Baraniecki, A. Sauvlet, H. Habenicht, W. Fiedler, B. Berger, H. Goldstein, S. Fiumara, P. Spoor, S. Stilzen, H. Fiedler, A. -

Country Christmas ...2 Rhythm

1 Ho li day se asons and va ca tions Fei er tag und Be triebs fe rien BEAR FAMILY will be on Christmas ho li days from Vom 23. De zem ber bis zum 10. Ja nuar macht De cem ber 23rd to Ja nuary 10th. During that peri od BEAR FAMILY Weihnach tsfe rien. Bestel len Sie in die ser plea se send written orders only. The staff will be back Zeit bitte nur schriftlich. Ab dem 10. Janu ar 2005 sind ser ving you du ring our re gu lar bu si ness hours on Mon- wir wie der für Sie da. day 10th, 2004. We would like to thank all our custo - Bei die ser Ge le gen heit be dan ken wir uns für die gute mers for their co-opera ti on in 2004. It has been a Zu sam men ar beit im ver gan ge nen Jahr. plea su re wor king with you. BEAR FAMILY is wis hing you a Wir wünschen Ihnen ein fro hes Weih nachts- Merry Christmas and a Happy New Year. fest und ein glüc kliches neu es Jahr. COUNTRY CHRISTMAS ..........2 BEAT, 60s/70s ..................86 COUNTRY .........................8 SURF .............................92 AMERICANA/ROOTS/ALT. .............25 REVIVAL/NEO ROCKABILLY ............93 OUTLAWS/SINGER-SONGWRITER .......25 PSYCHOBILLY ......................97 WESTERN..........................31 BRITISH R&R ........................98 WESTERN SWING....................32 SKIFFLE ...........................100 TRUCKS & TRAINS ...................32 INSTRUMENTAL R&R/BEAT .............100 C&W SOUNDTRACKS.................33 C&W SPECIAL COLLECTIONS...........33 POP.............................102 COUNTRY CANADA..................33 POP INSTRUMENTAL .................108 COUNTRY -

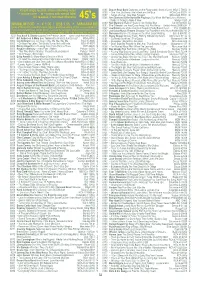

Minimum Bod = 6 1.00 / Us$ 1.15 = Minimum

45 rpm single records, unless otherwise noted 6085 Desert Rose Band Darkness on the Playground | Story of Love MCA-C 79052 N 6086 ~ One That Got Away | He’s Back and I’m Blue MCA-Curb 53274 N * = picture cover · pr = promo with special label 6087 ~ Ashes of Love | One Step Forward MCA-Curb 53531 N US releases, if not noted otherwise 45's 6088 Ann Diamond & the Nashville Playboys You Make Me Feel Like a Woman | I Think I’m Going to Make It Now Marilyn 7063 N 6089* Neil Diamond Walk on Water | High Rolling Man Uni 6073045\D Zg MINIMUM BOD = € 1.00 / US$ 1.15 = MINIMUM BID 6090 The Dillards Love Has Gone Away | Hot Rod Banjo United Artists 35660\UK Z Some of these 45’s come from radio stations and have writing and/or stickers on labels. 6091* Joe Dolan Love of the Common People | Pretty Brown Eyes Pye 11088\D Zg If you do not want those, let me know! - Een aantal van deze singles komt van radio sta- 6092* Joe Dolce Music Theatre Shaddap You Face|Ain’t in No HurryAriola102947\D Zz tions, waar men op labels schreef en/of stickers plakte. Wilt u die niet, laat het me weten! 6093 Donovan Atlantis | To Susan on the West Coast Waiting Epic 5-9967\D G 6233 Roy Acuff & Charlie Louvin The Precious Jewel (gold vinyl) Hal Kat 63058 Z 6094 Rusty Draper Mystery Train | Shifting Whispering Sands Monument 944 pr N 6001 Bill Anderson & Mary Lou Turner Way Ahead | Just Enough MCA 40852 Z 6095 ~ California Sunshine | The Gypsy Monument 1044 N 6002 Liz Anderson Cry, Cry Again | Me, Me, Me, Me, Me RCA 47-9586 Z 6096 ~ Puppeteer | My Baby’s Not Here Monument