Special Issue: Early Career Researchers V

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reid Hall Columbia Global Centers | Paris

Reid Hall Reid Academic Year 2016 – 2017 Columbia Global Centers | Paris Annual Report “ The best semester of my life.” DIEGO RODRIGUEZ, ARCHITECTURE PROGRAM Contents “During my time at Reid Hall, I not only benefited from exceptional professors from Columbia’s campus and at Paris IV, but also had my perspective of the world drastically expanded. Advisory Board & Faculty Steering Committee 2 Between living with host families and interacting Letter from President Lee C. Bollinger 4 with other students—both those in my program Letter from EVP Safwan M. Masri 5 and those at French universities—I gained the Introduction, Paul LeClerc, Director 6 ability to analyze and critique the American and Reid Hall, Une réhabilitation, the French ways of life. I became so enamored Brunhilde Biebuyck, Administrative Director 10 by the latter that, while initially only intending to The Columbia Institute for Ideas and Imagination 13 Fall, Spring, & Summer Academic Programs 16 spend one semester MA in History and Literature 16 Whether or not a The Shape of Two Cities: Paris Spring Term 20 abroad, I have Columbia Undergraduate Programs in Paris, Fall & Spring Terms 22 chosen to stay in student intends Columbia Undergraduate Programs in Paris, France to continue Summer Term 25 to do the same, Other Summer Academic Programs 27 my studies. Alliance Graduate Summer School 27 I recommend a Senior Thesis Research in Europe 30 Public Programs 31 study abroad at Paris Center Programming 31 Columbia Sounds at Reid Hall 33 Reid Hall without Columbia University Alumni Club of France 34 Programs Organized by CGC l Paris 36 ” hesitation. -

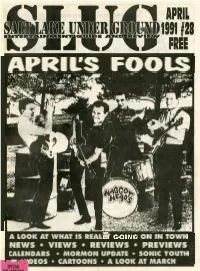

April's Fools

APRIL'S FOOLS ' A LOOK AT WHAT IS REAL f ( i ON IN. TOWN NEWS VIEWS . REVIEWS PREVIEWS CALENDARS MORMON UPDATE SONIC YOUTH -"'DEOS CARTOONS A LOOK AT MARCH frlday, april5 $7 NOMEANSNO, vlcnms FAMILYI POWERSLAVI saturday, april 6 $5 an 1 1 piece ska bcnd from cdlfomb SPECKS witb SWlM HERSCHEL SWIM & sunday,aprll7 $5 from washln on d.c. m JAWBO%, THE STENCH wednesday, aprl10 KRWTOR, BLITZPEER, MMGOTH tMets $10raunch, hemmetal shoD I SUNDAY. APRIL 7 I INgTtD, REALITY, S- saturday. aprll $5 -1 - from bs aqdes, califomla HARUM SCAIUM, MAG&EADS,;~ monday. aprlll5 free 4-8. MAtERldl ISSUE, IDAHO SYNDROME wedn apri 17 $5 DO^ MEAN MAYBE, SPOT fiday. am 19 $4 STILL UFEI ALCOHOL DEATH saturday, april20 $4 SHADOWPLAY gooah TBA mday, 26 Ih. rlrdwuhr tour from a land N~AWDEATH, ~O~LESH;NOCTURNUS tickets $10 heavy metal shop, raunch MATERIAL ISSUE I -PRIL 15 I comina in mayP8 TFL, TREE PEOPLE, SLaM SUZANNE, ALL, UFT INSANE WARLOCK PINCHERS, MORE MONDAY, APRIL 29 I DEAR DICKHEADS k My fellow Americans, though:~eopledo jump around and just as innowtiwe, do your thing let and CLIJG ~~t of a to NW slam like they're at a punk show. otherf do theirs, you sounded almost as ENTEIWAINMENT man for hispoeitivereviewof SWIM Unfortunately in Utah, people seem kd as L.L. "Cwl Guy" Smith. If you. GUIIBE ANIB HERSCHELSWIMsdebutecassette. to think that if the music is fast, you are that serious, I imagine we will see I'mnotamemberofthebancljustan have to slam, but we're doing our you and your clan at The Specks on IMVIEW avid ska fan, and it's nice to know best to teach the kids to skank cor- Sahcr+nightgiwingskrmkin'Jessom. -

Irish Gothic Fiction

THE ‘If the Gothic emerges in the shadows cast by modernity and its pasts, Ireland proved EME an unhappy haunting ground for the new genre. In this incisive study, Jarlath Killeen shows how the struggle of the Anglican establishment between competing myths of civility and barbarism in eighteenth-century Ireland defined itself repeatedly in terms R The Emergence of of the excesses of Gothic form.’ GENCE Luke Gibbons, National University of Ireland (Maynooth), author of Gaelic Gothic ‘A work of passion and precision which explains why and how Ireland has been not only a background site but also a major imaginative source of Gothic writing. IRISH GOTHIC Jarlath Killeen moves well beyond narrowly political readings of Irish Gothic by OF IRISH GOTHIC using the form as a way of narrating the history of the Anglican faith in Ireland. He reintroduces many forgotten old books into the debate, thereby making some of the more familiar texts seem suddenly strange and definitely troubling. With FICTION his characteristic blend of intellectual audacity and scholarly rigour, he reminds us that each text from previous centuries was written at the mercy of its immediate moment as a crucial intervention in a developing debate – and by this brilliant HIST ORY, O RIGI NS,THE ORIES historicising of the material he indicates a way forward for Gothic amidst the ruins of post-Tiger Ireland.’ Declan Kiberd, University of Notre Dame Provides a new account of the emergence of Irish Gothic fiction in the mid-eighteenth century FI This new study provides a robustly theorised and thoroughly historicised account of CTI the beginnings of Irish Gothic fiction, maps the theoretical terrain covered by other critics, and puts forward a new history of the emergence of the genre in Ireland. -

Copyright by Katharine Elizabeth Beutner 2011

Copyright by Katharine Elizabeth Beutner 2011 The Dissertation Committee for Katharine Elizabeth Beutner certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Writing for Pleasure or Necessity: Conflict among Literary Women, 1700-1750 Committee: ____________________________________ Lance Bertelsen, Supervisor ____________________________________ Janine Barchas ____________________________________ Elizabeth Cullingford ____________________________________ Margaret Ezell ____________________________________ Catherine Ingrassia Writing for Pleasure or Necessity: Conflict among Literary Women, 1700-1750 by Katharine Elizabeth Beutner, B.A.; M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin May 2011 Acknowledgments My thanks to the members of my dissertation committee—Janine Barchas, Elizabeth Cullingford, Margaret Ezell, and Catherine Ingrassia—for their wise and patient guidance as I completed this project. Thanks are also due to Elizabeth Hedrick, Michael Adams, Elizabeth Harris, Tom Cable, Samuel Baker, and Wayne Lesser for all the ways they’ve shaped my graduate career. Kathryn King, Patricia Hamilton, Jennie Batchelor, and Susan Carlile encouraged my studies of eighteenth-century women writers; Al Coppola graciously sent me a copy of his article on Eliza Haywood’s Works pre-publication. Thanks to Matthew Reilly for comments on an early version of the Manley material and to Jessica Kilgore for advice and good cheer. My final year of writing was supported by the Carolyn Lindley Cooley, Ph.D. Named PEO Scholar Award and by a Dissertation Fellowship from the American Association of University Women. I want to express my gratitude to both organizations. -

The Oxford Companion to English Literature, 6Th Edition

e cabal, from the Hebrew word qabbalah, a secret an elderly man. He is said by *Bede to have been an intrigue of a sinister character formed by a small unlearned herdsman who received suddenly, in a body of persons; or a small body of persons engaged in vision, the power of song, and later put into English such an intrigue; in British history applied specially to verse passages translated to him from the Scriptures. the five ministers of Charles II who signed the treaty of The name Caedmon cannot be explained in English, alliance with France for war against Holland in 1672; and has been conjectured to be Celtic (an adaptation of these were Clifford, Arlington, *Buckingham, Ashley the British Catumanus). In 1655 François Dujon (see SHAFTESBURY, first earl of), and Lauderdale, the (Franciscus Junius) published at Amsterdam from initials of whose names thus arranged happened to the unique Bodleian MS Junius II (c.1000) long scrip form the word 'cabal' [0£D]. tural poems, which he took to be those of Casdmon. These are * Genesis, * Exodus, *Daniel, and * Christ and Cade, Jack, Rebellion of, a popular revolt by the men of Satan, but they cannot be the work of Caedmon. The Kent in June and July 1450, Yorkist in sympathy, only work which can be attributed to him is the short against the misrule of Henry VI and his council. Its 'Hymn of Creation', quoted by Bede, which survives in intent was more to reform political administration several manuscripts of Bede in various dialects. than to create social upheaval, as the revolt of 1381 had attempted. -

A Journal of the Center for Complex Operations Vol. 4, No. 3

VOL. 4, NO. 3 2013 A JOURNA L O F THE CEN TER F OR C O MPL EX O PER ATIONS About PRISM is published by the Center for Complex Operations. PRISM is a security studies journal chartered to inform members of U.S. Federal agencies, allies, Vol. 4, no. 3 2013 and other partners on complex and integrated national security operations; reconstruction and state-building; relevant policy and strategy; lessons learned; Editor and developments in training and education to transform America’s security Michael Miklaucic and development Associate Editors Mark D. Ducasse Stefano Santamato Communications Constructive comments and contributions are important to us. Direct Editorial Assistant communications to: Megan Cody Editor, PRISM Copy Editors 260 Fifth Avenue (Building 64, Room 3605) Dale Erikson Fort Lesley J. McNair Sara Thannhauser Washington, DC 20319 Nathan White Telephone: (202) 685-3442 Advisory Board FAX: Dr. Gordon Adams (202) 685-3581 Dr. Pauline H. Baker Email: [email protected] Ambassador Rick Barton Professor Alain Bauer Dr. Joseph J. Collins (ex officio) Ambassador James F. Dobbins Contributions Ambassador John E. Herbst (ex officio) PRISM welcomes submission of scholarly, independent research from security policymakers and shapers, security analysts, academic specialists, and civilians Dr. David Kilcullen from the United States and abroad. Submit articles for consideration to the Ambassador Jacques Paul Klein address above or by email to [email protected] with “Attention Submissions Dr. Roger B. Myerson Editor” in the subject line. Dr. Moisés Naím This is the authoritative, official U.S. Department of Defense edition of PRISM. MG William L. Nash, USA (Ret.) Any copyrighted portions of this journal may not be reproduced or extracted Ambassador Thomas R. -

John Boydell's Shakespeare Gallery and the Promotion of a National Aesthetic

JOHN BOYDELL'S SHAKESPEARE GALLERY AND THE PROMOTION OF A NATIONAL AESTHETIC ROSEMARIE DIAS TWO VOLUMES VOLUME I PHD THE UNIVERSITY OF YORK HISTORY OF ART SEPTEMBER 2003 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Volume I Abstract 3 List of Illustrations 4 Introduction 11 I Creating a Space for English Art 30 II Reynolds, Boydell and Northcote: Negotiating the Ideology 85 of the English Aesthetic. III "The Shakespeare of the Canvas": Fuseli and the 154 Construction of English Artistic Genius IV "Another Hogarth is Known": Robert Smirke's Seven Ages 203 of Man and the Construction of the English School V Pall Mall and Beyond: The Reception and Consumption of 244 Boydell's Shakespeare after 1793 290 Conclusion Bibliography 293 Volume II Illustrations 3 ABSTRACT This thesis offers a new analysis of John Boydell's Shakespeare Gallery, an exhibition venture operating in London between 1789 and 1805. It explores a number of trajectories embarked upon by Boydell and his artists in their collective attempt to promote an English aesthetic. It broadly argues that the Shakespeare Gallery offered an antidote to a variety of perceived problems which had emerged at the Royal Academy over the previous twenty years, defining itself against Academic theory and practice. Identifying and examining the cluster of spatial, ideological and aesthetic concerns which characterised the Shakespeare Gallery, my research suggests that the Gallery promoted a vision for a national art form which corresponded to contemporary senses of English cultural and political identity, and takes issue with current art-historical perceptions about the 'failure' of Boydell's scheme. The introduction maps out some of the existing scholarship in this area and exposes the gaps which art historians have previously left in our understanding of the Shakespeare Gallery. -

How the History of Female Presidential Candidates Affects Political Ambition and Engagement Kaycee Babb Boise State University GIRLS JUST WANNA BE PRESIDENT

Boise State University ScholarWorks History Graduate Projects and Theses Department of History 5-1-2017 Girls Just Wanna Be President: How the History of Female Presidential Candidates Affects Political Ambition and Engagement KayCee Babb Boise State University GIRLS JUST WANNA BE PRESIDENT: HOW THE HISTORY OF FEMALE PRESIDENTIAL CANDIDATES AFFECTS POLITICAL AMBITION AND ENGAGEMENT by KayCee Babb A project submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Applied Historical Research Boise State University May 2017 © 2017 KayCee Babb ALL RIGHTS RESERVED BOISE STATE UNIVERSITY GRADUATE COLLEGE DEFENSE COMMITTEE AND FINAL READING APPROVALS of the thesis submitted by KayCee Babb Thesis Title: Girls Just Wanna Be President: The Impact of the History of Female Presidential Candidates on Political Ambition and Engagement Date of Final Oral Examination: April 13, 2017 The following individuals read and discussed the thesis submitted by student KayCee Babb, and they evaluated her presentation and response to questions during the final oral examination. They found that the student passed the final oral examination. Jill Gill, Ph.D. Chair, Supervisory Committee Jaclyn Kettler, Ph.D. Member, Supervisory Committee Leslie Madsen-Brooks, Ph.D. Member, Supervisory Committee The final reading approval of the thesis was granted by Jill Gill, Ph.D., Chair of the Supervisory Committee. The thesis was approved for the Graduate College by Tammi Vacha-Haase, Ph.D., Dean of the Graduate College. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would first like to thank my thesis advisor Dr. Jill Gill from the History Department at Boise State University. Their office door was always open for questions, but more often for the expression of stress and frustration that I had built up during these last two years. -

"Theater and Empire: a History of Assumptions in the English-Speaking Atlantic World, 1700-1860"

"THEATER AND EMPIRE: A HISTORY OF ASSUMPTIONS IN THE ENGLISH-SPEAKING ATLANTIC WORLD, 1700-1860" BY ©2008 Douglas S. Harvey Submitted to the graduate degree program in History and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. ____________________________________ Chairperson Committee Members* ___________________________________* ___________________________________* ___________________________________* ___________________________________* Date Defended: April 7, 2008 The Dissertation Committee for Douglas S. Harvey certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: "THEATER AND EMPIRE: A HISTORY OF ASSUMPTIONS IN THE ENGLISH-SPEAKING ATLANTIC WORLD, 1700-1860" Committee ____________________________________ Chairperson ___________________________________* ___________________________________* ___________________________________* ___________________________________* Date Approved: April 7, 2008 ii Abstract It was no coincidence that commercial theater, a market society, the British middle class, and the “first” British Empire arose more or less simultaneously. In the seventeenth century, the new market economic paradigm became increasingly dominant, replacing the old feudal economy. Theater functioned to “explain” this arrangement to the general populace and gradually it became part of what I call a “culture of empire” – a culture built up around the search for resources and markets that characterized imperial expansion. It also rationalized the depredations the Empire brought to those whose resources and labor were coveted by expansionists. This process intensified with the independence of the thirteen North American colonies, and theater began representing Native Americans and African American populations in ways that rationalized the dominant society’s behavior toward them. By utilizing an interdisciplinary approach, this research attempts to advance a more nuanced and realistic narrative of empire in the early modern and early republic periods. -

Friday, November 16

FRIDAY, NOVEMBER 16 v 7:00–7:45 A.M. First-Timers’ Welcome GRAND BALLROOM A Ernest Morrell Set your alarm so you don’t miss this event we’re holding just for you! Join first-time attendees and NCTE leaders for an informative session to kick off your NCTE annual convention experience. You’ll have the opportunity to hear from NCTE members Ernest Morrell and Donalyn Miller as well as connect with other NCTE members. The special gathering provides an opportunity for you to gain quick tips and strategies that will expand your knowledge of Donalyn Miller NCTE and your professional network. 56 2018 NCTE ANNUAL CONVENTION PROGRAM FRIDAY GENERAL SESSION v 8:00–9:15 A.M. Students Raising Their Voices Antero Garcia GENERAL ASSEMBLY THEATER ABC FRIDAY Presiding: Antero Garcia, Stanford University, CA Kristin Ziemke, Big Shoulders Project, Chicago, IL Friday’s General Session will be fast and full of energy. This session will be a celebration of students who are using their voices to change the world and will be facilitated by NCTE members Antero Garcia and Kristin Ziemke. Seven students Kristin Ziemke ages 11 to 21 will share their passions with attendees. Speakers at this session include students who have created movements or organizations, raising their voices to create change. After the session, books pre-signed by Marley will be on hand and she will be available for photo ops. Andrea Cipriani Mecchi Andrea Marley Dias Alex King Xiuhtezcatl Martinez Social activist behind Student advocate Indigenous climate activist #1000blackgirlbooks for gun reform and hip-hop artist Sara Abou Rashed Zephyrus Todd Olivia Van Ledjte Jordyn Zimmerman Inspirational multilingual Student and social Reader, thinker, and Avid speaker and poet and author media creator kids’ voice believer advocate for all students 20182018 NCTE NCE ANNUAL CONVENTION PROGRAM 57 C SESSIONS / 9:30–10:45 A.M. -

'Words Which Could Only Be Your Own': the Crossroad Between Lyrics

- 1 - Ministério da Educação Universidade Federal dos Vales do Jequitinhonha e Mucuri – UFVJM Minas Gerais – Brasil Revista Vozes dos Vales: Publicações Acadêmicas Reg.: 120.2.095–2011 – UFVJM ISSN: 2238-6424 Nº. 02 – Ano I – 10/2012 http://www.ufvjm.edu.br/vozes ‘Words which could only be your own’: the crossroad between lyrics translation, culture, Brazilian fans, and non-professional translators Luciana Kaross PhD Candidate in Translation and Intercultural Studies School of Arts, Languages and Cultures The University of Manchester, Lancashire, UK E-mail: [email protected] Renata Spinola Doutoranda em Literatura e Cultura Instituto de Letras Universidade Federal da Bahia, Bahia, Brasil E-mail: [email protected] Resumo: Nos estudos da tradução, um tópico que tem rendido discussões interessantes se apoia na intervenção do tradutor no que se refere à transferência de aspectos culturais do texto de origem para o texto de chegada. No entanto, a pesquisa concernente à tradução da música pop para fins de entendimento tem sido negligenciada. As diferentes mídias em que letras traduzidas podem ser encontradas no Brasil e os diversos perfis de seus tradutores proporcionam um campo de estudo ainda inexplorado. Esse artigo tem por objetivo estabelecer até que ponto as fontes de acesso às letras traduzidas domesticam ou estrangeirizam os aspectos culturais presentes nas letras do cantor Morrissey. Apesar de não baseado em técnicas acadêmicas, mas em aprendizado empírico, o trabalho coletivo dos fãs produz um texto final de boa qualidade. Palavras-chave: Tradução. Prática metodológica, Cultura. Letras de Música. Tradutores amadores. Revista Vozes dos Vales da UFVJM: Publicações Acadêmicas – MG – Brasil – Nº 02 – Ano I – 10/2012 Reg.: 120.2.095–2011 – PROEXC/UFVJM – ISSN: 2238-6424 – www.ufvjm.edu.br/vozes - 2 - Introduction The importance of popular music in the Brazilian Culture is undeniable. -

Columbia Global Centers | Amman

Columbia Global Centers | Amman .............................................................................................. 3 Columbia Global Centers | Beijing ............................................................................................. 17 Columbia Global Centers | Istanbul ............................................................................................ 30 Columbia Global Centers | Mumbai ........................................................................................... 41 Columbia Global Centers | Nairobi ............................................................................................. 48 Columbia Global Centers | Paris ................................................................................................. 52 Columbia Global Centers | Rio de Janeiro ................................................................................. 62 Columbia Global Centers | Santiago ........................................................................................... 69 Columbia Global Centers | Tunis ................................................................................................ 77 Columbia Global Centers | Amman Center Launch: March 2009 Website: http://globalcenters.columbia.edu/amman Email: [email protected] Address: 5 Moh’d Al Sa’d Al Batayneh St., King Hussein Park, P.O. Box 144706, Amman 11814 Jordan Director Biography SAFWAN M. MASRI [email protected] Professor Safwan M. Masri is Executive Vice President for Global Centers and Global Development at Columbia