Twana and the Difficult Language Belief*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

North: Lummi, Nooksack, Samish, Sauk-Suiattle, Stillaguamish

Policy 7.01 Implementation Plan Region 2 North (R2N) Community Services Division (CSD) Serving the following Tribes: Lummi Nation, Nooksack Indian Tribe, Samish Indian Nation, Sauk-Suiattle Indian Tribe, Stillaguamish Tribe of Indians, Swinomish Tribal Community, Tulalip Tribes, & Upper Skagit Indian Tribe Biennium Timeframe: July 1, 2021 to June 30, 2022 Revised 04/2021 Annual Key Due Dates: April 1st - CSD Regional Administrators submit 7.01 Plan and Progress Reports (PPRs) to CSD HQ Coordinator. April 13th – CSD HQ Coordinator will submit Executive Summary & 7.01 PPRs to the ESA Office of Assistant Secretary for final review. April 23rd - ESA Office of the Assistant Secretary will send all 7.01 PPRs to Office of Indian Policy (OIP). 7.01 Meetings: January 17th- Cancelled due to inclement weather Next scheduled meeting April 17th, hosted by the Nooksack Indian Tribe. 07/07/20 Virtual 7.01 meeting. 10/16/20 7.01 Virtual meeting 01/15/21 7.01 Virtual 04/16/21 7.01 Virtual 07/16/21 7.01 Virtual Implementation Plan Progress Report Status Update for the Fiscal Year Goals/Objectives Activities Expected Outcome Lead Staff and Target Date Starting Last July 1 Revised 04/2021 Page 1 of 27 1. Work with tribes Lead Staff: to develop Denise Kelly 08/16/2019 North 7.01 Meeting hosted by services, local [email protected] , Tulalip Tribes agreements, and DSHS/CSD Tribal Liaison Memorandums of 10/18/2019 North 7.01 Meeting hosted by Understanding Dan Story, DSHS- Everett (MOUs) that best [email protected] meet the needs of Community Relations 01/17/2020 North 7.01 Meeting Region 2’s Administrator/CSD/ESA scheduled to be hosted by Upper Skagit American Indians. -

Tribal Element

Tribal Element Three federally-recognized Indian Tribes, the Sauk-Suiattle Tribe, the Stillaguamish Tribe, and the Tulalip Tribes, occupy areas of present-day Snohomish County. These Tribes and their ancestors are a land and water based people, part of a larger group of aboriginal Tribes and First Nations known as the Coast Salish peoples, who live around the Salish Sea in what is now Washington State and the Canadian Province of British Columbia. The Coast Salish Tribes and First Nations have lived here since time immemorial, enjoying a landscape rich in natural resources. Coast Salish lifeways are tied to the natural environment of the Pacific Northwest, especially the Salish Sea. Today the Sauk-Suiattle, Stillaguamish, and the Tulalip Tribes are sovereign nations recognized by the United States government. Each Tribe has its own government with its own governing charter or constitution and set of general laws. These Tribes reserved lands in what is now Snohomish County as Indian reservation homelands. The Tribes have important historic and cultural sites both on and off their reservations. Each Tribe continues to exercise off-reservation rights reserved under treaty with the United States, including the right to fish in usual and accustomed fishing grounds and the right to hunt and gather on open and unclaimed lands. Snohomish County acknowledges the historic and present-day connection between tribal people and the land base, and recognizes each Tribe’s sovereignty. Snohomish County is committed to partnering with the Tribes to protect and preserve Tribal cultural and treaty resources, the natural environment, and sacred cultural areas. The relationship between these Tribes and Snohomish County is especially important when activities of county government, particularly land use regulation, have implications for one or more Tribes. -

Hylebos Watershed Plan

Hylebos Watershed Plan July 2016 EarthCorps 6310 NE 74th Street, Suite 201E Seattle, WA 98115 Prepared by: Matt Schwartz, Project Manager Nelson Salisbury, Ecologist William Brosseau, Operations Director Pipo Bui, Director of Foundation and Corporate Relations Rob Anderson, Senior Project Manager Acknowledgements Support for the Hylebos Watershed Plan is provided by the Puget Sound Stewardship and Mitigation Fund, a grantmaking fund created by the Puget Soundkeeper Alliance and administered by the Rose Foundation for Communities and the Environment. Hylebos Watershed Plan- EarthCorps 2016 | 1 June 28, 2016 Table of Contents 1 Introduction ................................................................................................................................................................ 4 1.1 History of EarthCorps/Friends of the Hylebos ........................................................................................................ 4 1.2 Key Stakeholders ..................................................................................................................................................... 5 2 Purpose of Report- The Why ............................................................................................................................... 7 3 Goals and Process- The What and The How ................................................................................................... 8 3.1 Planning Process .................................................................................................................................................... -

Saanich Morphology and Phonology' Is Based on Field Work Carried out During the Summers of 1978 Through 1981

An Outline of the Morphology and Phonology of Saanich 07/05/2005 10:08 AM PREFACE This slightly revised version of my 1984 University of Hawaii dissertaion 'Saanich Morphology and Phonology' is based on field work carried out during the summers of 1978 through 1981. I have since been back to Saanich country and worked with a number of other speakers. The analyses presented here have, for the most part, been confirmed. At least the basic distributional properties of the forms discussed here seem to be correct. I have, however, discovered a few lexical suffixes and post-predicate particles not mentioned here. The analyes I have been rethinking are those of the reduplicative processes and the demonstrative particles. I now feel that at least soem of the reduplicative processes analyzed as vowelless with a subsequent insertion of schwa might be better analyzed as having an underlying full vowel that reduces when unstressed. The problems with the demonstratives involve the two formatives referring to place and their relationship to a preposition /ƛ̕əʔ/ which indicates direction toward a specific place. It is my hope that this work will be useful despite its holes. They will never be all patched; "all grammars leak." A Elsie Claxton put it when as a summer was coming to an end I expressed to her how much more I wanted to learn about her language: "sk̕ʷey kʷs ʔaw̕k̕ʷs." There's no end to it. Research for this work was supported by grants from the National Science Foundation and the National Endowment for the Humanities through the Northwest Indian Languages Studies Project under the direction of Professor Laurence C. -

An Examination of Nuu-Chah-Nulth Culture History

SINCE KWATYAT LIVED ON EARTH: AN EXAMINATION OF NUU-CHAH-NULTH CULTURE HISTORY Alan D. McMillan B.A., University of Saskatchewan M.A., University of British Columbia THESIS SUBMI'ITED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in the Department of Archaeology O Alan D. McMillan SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY January 1996 All rights reserved. This work may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without permission of the author. APPROVAL Name: Alan D. McMillan Degree Doctor of Philosophy Title of Thesis Since Kwatyat Lived on Earth: An Examination of Nuu-chah-nulth Culture History Examining Committe: Chair: J. Nance Roy L. Carlson Senior Supervisor Philip M. Hobler David V. Burley Internal External Examiner Madonna L. Moss Department of Anthropology, University of Oregon External Examiner Date Approved: krb,,,) 1s lwb PARTIAL COPYRIGHT LICENSE I hereby grant to Simon Fraser University the right to lend my thesis, project or extended essay (the title of which is shown below) to users of the Simon Fraser University Library, and to make partial or single copies only for such users or in response to a request from the library of any other university, or other educational institution, on its own behalf or for one of its users. I further agree that permission for multiple copying of this work for scholarly purposes may be granted by me or the Dean of Graduate Studies. It is understood that copying or publication of this work for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. -

Section II Community Profile

Section II: Community Profile Section II Community Profile Hazard Mitigation Plan 2010 Update 9 [this page intentionally left blank] 10 Hazard Mitigation Plan 2010 Update Section II: Community Profile Community Profile Disclaimer: The Tulalip Tribes Tribal/State Hazard Mitigation Plan covers all the people, property, infrastructure and natural environment within the exterior boundaries of the Tulalip Reservation as established by the Point Elliott Treaty of January 22, 1855 and by Executive Order of December 23, 1873, as well as any property owned by the Tulalip Tribes outside of this area. Furthermore the Plan covers the Tulalip Tribes Usual and Accustom Fishing areas (U&A) as determined by Judge Walter E. Craig in United States of America et. al., plaintiffs v. State of Washington et. al., defendant, Civil 9213 Phase I, Sub Proceeding 80-1, “In Re: Tulalip Tribes’ Request for Determination of Usual and Accustom Fishing Places.” This planning scope does not limit in any way the Tulalip Tribes’ hazard mitigation and emergency management planning concerns or influence. This section will provide detailed information on the history, geography, climate, land use, population and economy of the Tulalip Tribes and its Reservation. Tulalip Reservation History Archaeologists and historians estimate that Native Americans arrived from Siberia via the Bering Sea land bridge beginning 17,000 to 11,000 years ago in a series of migratory waves during the end of the last Ice Age. Indians in the region share a similar cultural heritage based on a life focused on the bays and rivers of Puget Sound. Throughout the Puget Sound region, While seafood was a mainstay of the native diet, cedar trees were the most important building material.there were Cedar numerous was used small to tribesbuild both that subsistedlonghouses on and salmon, large halibut,canoes. -

Battlefields & Treaties

welcome to Indian Country Take a moment, and look up from where you are right now. If you are gazing across the waters of Puget Sound, realize that Indian peoples thrived all along her shoreline in intimate balance with the natural world, long before Europeans arrived here. If Mount Rainier stands in your view, realize that Indian peoples named it “Tahoma,” long before it was “discovered” by white explorers. Every mountain that you see on the horizon, every stand of forest, every lake and river, every desert vista in eastern Washington, all of these beautiful places are part of our Indian heritage, and carry the songs of our ancestors in the wind. As we have always known, all of Washington State is Indian Country. To get a sense of our connection to these lands, you need only to look at a map of Washington. Over 75 rivers, 13 counties, and hundreds of cities and towns all bear traditional Indian names – Seattle, Tacoma, Yakima, and Spokane among them. Indian peoples guided Lewis and Clark to the Pacifi c, and pointed them safely back to the east. Indian trails became Washington’s earliest roads. Wild salmon, delicately grilled and smoked in Alderwood, has become the hallmark of Washington State cuisine. Come visit our lands, and come learn about our cultures and our peoples. Our families continue to be intimately woven into the world around us. As Tribes, we will always fi ght for preservation of our natural resources. As Tribes, we will always hold our elders and our ancestors in respect. As Tribes, we will always protect our treaty rights and sovereignty, because these are rights preserved, at great sacrifi ce, ABOUT ATNI/EDC by our ancestors. -

Anthropological Study of Yakama Tribe

1 Anthropological Study of Yakama Tribe: Traditional Resource Harvest Sites West of the Crest of the Cascades Mountains in Washington State and below the Cascades of the Columbia River Eugene Hunn Department of Anthropology Box 353100 University of Washington Seattle, WA 98195-3100 [email protected] for State of Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife WDFW contract # 38030449 preliminary draft October 11, 2003 2 Table of Contents Acknowledgements 4 Executive Summary 5 Map 1 5f 1. Goals and scope of this report 6 2. Defining the relevant Indian groups 7 2.1. How Sahaptin names for Indian groups are formed 7 2.2. The Yakama Nation 8 Table 1: Yakama signatory tribes and bands 8 Table 2: Yakama headmen and chiefs 8-9 2.3. Who are the ―Klickitat‖? 10 2.4. Who are the ―Cascade Indians‖? 11 2.5. Who are the ―Cowlitz‖/Taitnapam? 11 2.6. The Plateau/Northwest Coast cultural divide: Treaty lines versus cultural 12 divides 2.6.1. The Handbook of North American Indians: Northwest Coast versus 13 Plateau 2.7. Conclusions 14 3. Historical questions 15 3.1. A brief summary of early Euroamerican influences in the region 15 3.2. How did Sahaptin-speakers end up west of the Cascade crest? 17 Map 2 18f 3.3. James Teit‘s hypothesis 18 3.4. Melville Jacobs‘s counter argument 19 4. The Taitnapam 21 4.1. Taitnapam sources 21 4.2. Taitnapam affiliations 22 4.3. Taitnapam territory 23 4.3.1. Jim Yoke and Lewy Costima on Taitnapam territory 24 4.4. -

Barbara Lane Fc^Ido. Date: September 27, 1993 «3*Sfs' Subject: Review of Data Re: Possible Native Presence Mountain Goat Olympic National Park

Memorandum O/JLcv VJ». To: Paul Gleeson l«vu/s- fx«£»*-4'5-lz.y From: Barbara Lane fc^ido. Date: September 27, 1993 «3*SfS' Subject: Review of data re: possible native presence mountain goat Olympic National Park Enclosed is a final copy of my report "Western Washington Indian Knowledge of Mountain Goat in the Nineteenth Century: Historic, Ethnographic, and Linguistic Data". Please substitute the enclosed for the copy sent to you earlier and destroy the earlier draft. On rereading the earlier paper I discovered numerous minor typographical and editorial matters which have been corrected in the final version enclosed herewith. Also enclosed is a signed copy of the contract associated with this project. Thank you for inviting me to participate in this review. I found the subject matter stimulating. Dr. Schultz's article is a real contribution to the history of exploration in the region. WY-U3-1WM ll^l^HH hKUTI IU l.fUb-O.iUJJ'} K.tU 1 Western Washington Indian Knowlege of Mountain Goat in the Nineteenth Century : Historic, Ethnographic, and Linguistic Data Introductory remarks This commentary is written in response to a request from the National Park Service for a review of materials concerning evidence relating to presence or absence of mountain goat in the Olympic Mountains prior to introduction of this species in the 1920s. Dr. Lyman (1988) noted that the view that mountain goat were not native to the Olympic Peninsula is based on an absence of biological reports, absence of historical and ethnographic records, and lack of archaeofaunal evidence of pre-1920s presence of the species in this region. -

Northwest Indian Fisheries Commission NEWS Vol

Northwest Indian Fisheries Commission NEWS Vol. XIV No. 3 Fall 1999 Inside: ■ Low Chum Returns ■ Razor Clam Beaches Open Again ■ Interview With Lorraine Loomis ■ Tribe Files Dam Suit ■ Project Targets Coho ■ Sharing A Tribal Tradition Being Frank At The Confluence Of The Centuries By Billy Frank Jr. NWIFC Chairman The confluence of the centuries I must ask myself, what kind of world will my sons should be like the joining of two riv- inherit in the years to come? ers. As they merge, the memories Researchers tell us that the ocean will rise several inches of countless moments and places over the next 50 years, and that its temperature will in- should fold one unto another, and crease by several degrees. form a deeper, broader flow of There’s a hole in the ozone layer. Exotic species of knowledge. predators are invading our waters. We’re told that there As the 19th Century merged into will be another million people here over the next 20 years the 20th, my father was a young and ground is still being lost to urban sprawl. man. He lived his whole life on the At the close of the 20th Century, I am striving to help Nisqually River. He was born in a wooden longhouse to teach my sons all I can of our heritage. I’m doing this be- parents who had lived on the same river throughout their cause I know it is their link to their traditional home on the lives. The heritage of the Nisqually has been passed from Nisqually, and their very existence as Indians. -

Shoreline Master Program Second Draft Comments

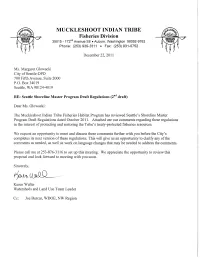

MUCKLESHOOT INDIAN TRIBE Fisheries Division 39015 - 172nd Avenue SE . Auburn, Washington 98092-9763 Phone: (253) 939-3311 . Fax: (253) 931-0752 December 22,2011 Ms. Margaret Glowacki City of Seattle-DPD 700 Fifth Avenue, Suite 2000 P.O. Box 34019 Seattle, WA 98124-4019 RE: Seattle Shoreline Master Program Draft Regulations (2nd draft) Dear Ms. Glowacki: The Muckleshoot Indian Tribe Fisheries Habitat Program has reviewed Seattle's Shoreline Master Program Draft Regulations dated October 2011. Attached are our comments regarding these regulations in the interest of protecting and restoring the Tribe's treaty-protected fisheries resources. We request an opportunity to meet and discuss these comments further with you before the City's completes its next version of these regulations. This wil give us an opportunity to clarify any of the comments as needed, as well as work on language changes that may be needed to address the comments. Please call me at 253-876-3116 to set up this meeting. We appreciate the opportunity to review this proposal and look forward to meeting with you soon. Sincerely, l)rJ,) (,_ ~'""fÎ(\ Karen Walter Watersheds and Land Use Team Leader Cc: Joe Burcar, WDOE, NW Region Muckleshoot Indian Tribe Fisheries Division December 22, 2011 Comments to Seattle's SMP regulations 2nd draft Page 2 Comments to the Shoreline Master Program Regulations-Second Draft, October 2011 General comments 1. Aquaculture should be allowed in all shoreline designations. It is a priority use under the Shoreline Management Act and important for the Tribe's fisheries programs. Under the draft rules, aquaculture is only allowed as a conditional use in the UC; UG; UH; UI; UM designations. -

Reduplicated Numerals in Salish. PUB DATE 1997-00-00 NOTE 11P.; for Complete Volume, See FL 025 251

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 419 409 FL 025 252 AUTHOR Anderson, Gregory D. S. TITLE Reduplicated Numerals in Salish. PUB DATE 1997-00-00 NOTE 11p.; For complete volume, see FL 025 251. PUB TYPE Journal Articles (080) Reports Research (143) JOURNAL CIT Kansas Working Papers in Linguistics; v22 n2 p1-10 1997 EDRS PRICE MF01/PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *American Indian Languages; Contrastive Linguistics; Language Patterns; *Language Research; Language Variation; *Linguistic Theory; Number Systems; *Salish; *Structural Analysis (Linguistics); Uncommonly Taught Languages ABSTRACT A salient characteristic of the morpho-lexical systems of the Salish languages is the widespread use of reduplication in both derivational and inflectional functions. Salish reduplication signals such typologically common categories as "distributive/plural," "repetitive/continuative," and "diminutive," the cross-linguistically marked but typically Salish notion of "out-of-control" or more restricted categories in particular Salish languages. In addition to these functions, reduplication also plays a role in numeral systems of the Salish languages. The basic forms of several numerals appear to be reduplicated throughout the Salish family. In addition, correspondences among the various Interior Salish languages suggest the association of certain reduplicative patterns with particular "counting forms" referring to specific nominal categories. While developments in the other Salish language are frequently more idiosyncratic and complex, comparative evidence suggests that the