Dek-Ev. Kta.Z W

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2014 National History Bee National Championships Round

2014 National History Bee National Championships Bee Finals BEE FINALS 1. Two men employed by this scientist, Jack Phillips and Harold Bride, were aboard the Titanic, though only the latter survived. A company named for this man was embroiled in an insider trading scandal involving Rufus Isaacs and Herbert Samuel, members of H.H. Asquith's cabinet. He shared the Nobel Prize with Karl Ferdinand Braun, and one of his first tests was aboard the SS Philadelphia, which managed a range of about two thousand miles for medium-wave transmissions. For the point, name this Italian inventor of the radio. ANSWER: Guglielmo Marconi 048-13-94-25101 2. A person with this surname died while piloting a plane and performing a loop over his office. Another person with this last name was embroiled in an arms-dealing scandal with the business Ottavio Quattrochi and was killed by a woman with an RDX-laden belt. This last name is held by "Sonia," an Italian-born Catholic who declined to become prime minister in 2004. A person with this last name declared "The Emergency" and split the Congress Party into two factions. For the point, name this last name shared by Sanjay, Rajiv, and Indira, the latter of whom served as prime ministers of India. ANSWER: Gandhi 048-13-94-25102 3. This man depicted an artist painting a dog's portrait with his family in satire of a dog tax. Following his father's commitment to Charenton asylum, this painter was forced to serve as a messenger boy for bailiffs, an experience which influenced his portrayals of courtroom scenes. -

“What Are Marines For?” the United States Marine Corps

“WHAT ARE MARINES FOR?” THE UNITED STATES MARINE CORPS IN THE CIVIL WAR ERA A Dissertation by MICHAEL EDWARD KRIVDO Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2011 Major Subject: History “What Are Marines For?” The United States Marine Corps in the Civil War Era Copyright 2011 Michael Edward Krivdo “WHAT ARE MARINES FOR?” THE UNITED STATES MARINE CORPS IN THE CIVIL WAR ERA A Dissertation by MICHAEL EDWARD KRIVDO Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Approved by: Chair of Committee, Joseph G. Dawson, III Committee Members, R. J. Q. Adams James C. Bradford Peter J. Hugill David Vaught Head of Department, Walter L. Buenger May 2011 Major Subject: History iii ABSTRACT “What Are Marines For?” The United States Marine Corps in the Civil War Era. (May 2011) Michael E. Krivdo, B.A., Texas A&M University; M.A., Texas A&M University Chair of Advisory Committee: Dr. Joseph G. Dawson, III This dissertation provides analysis on several areas of study related to the history of the United States Marine Corps in the Civil War Era. One element scrutinizes the efforts of Commandant Archibald Henderson to transform the Corps into a more nimble and professional organization. Henderson's initiatives are placed within the framework of the several fundamental changes that the U.S. Navy was undergoing as it worked to experiment with, acquire, and incorporate new naval technologies into its own operational concept. -

1 the Eugene D. Genovese and Elizabeth Fox-Genovese Library

The Eugene D. Genovese and Elizabeth Fox-Genovese Library Bibliography: with Annotations on marginalia, and condition. Compiled by Christian Goodwillie, 2017. Coastal Affair. Chapel Hill, NC: Institute for Southern Studies, 1982. Common Knowledge. Duke Univ. Press. Holdings: vol. 14, no. 1 (Winter 2008). Contains: "Elizabeth Fox-Genovese: First and Lasting Impressions" by Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham. Confederate Veteran Magazine. Harrisburg, PA: National Historical Society. Holdings: vol. 1, 1893 only. Continuity: A Journal of History. (1980-2003). Holdings: Number Nine, Fall, 1984, "Recovering Southern History." DeBow's Review and Industrial Resources, Statistics, etc. (1853-1864). Holdings: Volume 26 (1859), 28 (1860). Both volumes: Front flyleaf: Notes OK Both volumes badly water damaged, replace. Encyclopedia of Southern Baptists. Nashville: Broadman Press, 1958. Volumes 1 through 4: Front flyleaf: Notes OK Volume 2 Text block: scattered markings. Entrepasados: Revista De Historia. (1991-2012). 1 Holdings: number 8. Includes:"Entrevista a Eugene Genovese." Explorations in Economic History. (1969). Holdings: Vol. 4, no. 5 (October 1975). Contains three articles on slavery: Richard Sutch, "The Treatment Received by American Slaves: A Critical Review of the Evidence Presented in Time on the Cross"; Gavin Wright, "Slavery and the Cotton Boom"; and Richard K. Vedder, "The Slave Exploitation (Expropriation) Rate." Text block: scattered markings. Explorations in Economic History. Academic Press. Holdings: vol. 13, no. 1 (January 1976). Five Black Lives; the Autobiographies of Venture Smith, James Mars, William Grimes, the Rev. G.W. Offley, [and] James L. Smith. Documents of Black Connecticut; Variation: Documents of Black Connecticut. 1st ed. ed. Middletown: Conn., Wesleyan University Press, 1971. Badly water damaged, replace. -

![THE BUTLER Faiyfily L]V Aftie'.R.ICA](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9004/the-butler-faiyfily-l-v-aftie-r-ica-2019004.webp)

THE BUTLER Faiyfily L]V Aftie'.R.ICA

THE BUTLER FAiyfILY l]V AftiE'.R.ICA COMPILED BY WILLIAM DAVID BUTLER of St. Louis, Mo. JOHN CROMWELL BUTLER late of Denver, Col, JOSEPH MAR.ION BUTLER of Chicago, Ill. Published by SHALLCROSS PRINTING CO. St. Louis, Mo. THIS Boox IB DEDICATED TO THE BUTLER FAMILY IN AMERICA INTRODUCTION TO BUTLER HISTORY. In the history of these l!niteJ States, there are a few fami lies that have shone witb rare brilliancy from Colonial times, through the Revolution, the \Var of 1812, the ::-.rexican \Var and the great Civil conflict, down to the present time. Those of supe rior eminence may ~asily be numbered on the fingers and those of real supremacy in historical America are not more than a 1,andftil. They stand side by side, none e1wious of the others but all proud to do and dare, and, if need be, die for the nation. Richest and best types of citizens have they been from the pioneer days of ol!r earliest forefathers, and their descendants have never had occasion to apologize for any of them or to conceal any fact connected with their careers. Resplenclant in the beg-inning, their nobility of bloocl has been carrieJ uow11\\·arci pure and unstainecl. °'.\l)t :.ill ui Lheir Jcscenuants ha\·e been distinguished as the world ~·ues-the ,·:i~t majority of them ha\·e been content \\·ith rno<lest lines-bnt :dl ha\c been goocl citizens and faithful Americans. Ami what more hc>l!Or than that can be a,P.rclecl to them? . Coor<lim.te with the _·\clamses, of ::-.r:i.ss::iclrnseth. -

ABRAHAM LINCOLN’S WHITE DREAM (Johnson Publishing, 1999)

GO TO MASTER INDEX OF WARFARE 1 TWO PRESIDENTS, EMBODIMENTS OF AMERICAN RACISM “Lincoln must be seen as the embodiment, not the transcendence, of the American tradition of racism.” — Lerone Bennett, Jr., FORCED INTO GLORY: ABRAHAM LINCOLN’S WHITE DREAM (Johnson Publishing, 1999) 1. “Crosseyed people look funny.” — This is the 1st known image of Lincoln, a plate that was exposed in about 1846. Lincoln had a “lazy eye,” and at that early point the Daguerreotypists had not yet learned how to pose their subjects in order to evade the problem of one eye staring off at an angle. This wasn’t just Susan B. Anthony, and Francis Ellingwood Abbot, and Abraham Lincoln, and Jean-Paul Sartre, and Galileo Galilei, and Ben Turpin and Marty Feldman. Actually, this is a very general problem, with approximately one person out of every 25 to 50 suffering from some degree of strabismus (termed crossed eyes, lazy eye, turned eye, squint, double vision, floating, wandering, wayward, drifting, truant eyes, wall eyes described as having “one eye in York and the other in Cork”). Strabismus that is congenital, or develops in infancy, can create a brain condition known as amblyopia, in which to some degree the input from an eye are ignored although it is still capable of sight — or at least privileges inputs from the other eye. An article entitled “Was Rembrandt stereoblind?,” outlining research by Professor Margaret Livingstone of Harvard University and colleagues, was published in the September 14, 2004, issue of the _New England Journal of Medicine_. Rembrandt, a prolific painter of self-portraits, producing almost 100 if we include some 20 etchings. -

Chitlin Circuit at Kennedy Farm Long Version

(3200+ words) The Kennedy Farm From John Brown to James Brown A Place Ringing with Hope and History (Note: Because of the historical aspects of this article, and with the permission of several senior members of the Hagerstown African-American community, some dated synonyms for “African-Americans” have been employed.) The year is 1959. Negroes from Hagerstown, Winchester, Martinsburg and Charles Town have traveled over dark and potentially dangerous back-country roads to a common destination in southern Washington County, MD. Unbeknown to virtually the entire white community of the area, hundreds of colored people gather every weekend for a vital mission: to let the good times roll! Music-lovers spill out of jam-packed cars and stream toward the rhythmic sounds throbbing from a low-lying block building. Paying the cover charge (tonight it is $3), they duck inside to find the place in full swing. The large dance floor is packed with swaying bodies. Chairs ring the outside of the rectangular room, accommodating groups of young people engaged in lively conversation. The bartenders manning the long bar struggle to keep pace serving all the people eager to spend their hard-earned pay. At the far end of the long narrow structure, an electrifying entertainer dominates the scene. James Brown is on stage with his background vocalists, the Famous Flames. His instrumentalists, studded with pioneering rhythm and blues musicians from Little Richard’s former band, are laying down a funky groove. Brown’s footwork testifies that he once was an accomplished boxer. His sweat-drenched face gives credence to the claim that he is indeed the hardest working man in show business. -

Ish Santo Domingo, and Thus Rules the Entire Island

Civil Rights 43 educated Creole elite and French authorities, occupies the Span- ish Santo Domingo, and thus rules the entire island. 1797 The African-American Masonic Lodge is organized in Philadel- phia, Pennsylvania, by James Forten Jr., a sail maker and aboli- tionist; Absalom Jones of the African Episcopal Church; and Richard Allen of the African Methodist Episcopal Church. 1797 Four former slaves from North Carolina, now living free in Phila- delphia, Pennsylvania, petition the U.S. Congress to overturn North Carolina’s slave laws, which had been passed to counter the efforts of those who freed their slaves, and which allowed once freed slaves to be recaptured. The petitioners had to leave North Carolina and escape pursuit after their masters had freed them, but Congress does not accept their petition. 1798 The Alien and Sedition Acts passed by the U.S. Congress and signed by President John Adams give the president the power to expel any noncitizen posing a threat to the country and to muzzle the freedom of the press. The acts are opposed by Thomas Jeffer- son, then vice president, and James Madison and expire in 1801, during Jefferson’s presidency. 1798 The U.S. Congress passes the Naturalization Act, increasing the number of years an immigrant must live in the United States before applying for citizenship from 5 to 14. 1799 New York State passes a law beginning a gradual freeing of slaves. 1799 The Society for Missions in Africa and the East of the Church of England is founded in Great Britain to create missions in Africa and India in the hope that conversion, religious instruction, edu- cation, and self-improvement will end the slave trade. -

John Tyler Before the Presidency: Principles and Politics of a Southern Planter

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 2001 John Tyler Before the Presidency: Principles and Politics of a Southern Planter. Christopher Joseph Leahy Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Leahy, Christopher Joseph, "John Tyler Before the Presidency: Principles and Politics of a Southern Planter." (2001). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 242. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/242 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

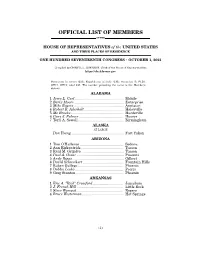

Official List of Members by State

OFFICIAL LIST OF MEMBERS OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES of the UNITED STATES AND THEIR PLACES OF RESIDENCE ONE HUNDRED SEVENTEENTH CONGRESS • OCTOBER 1, 2021 Compiled by CHERYL L. JOHNSON, Clerk of the House of Representatives https://clerk.house.gov Democrats in roman (220); Republicans in italic (212); vacancies (3) FL20, OH11, OH15; total 435. The number preceding the name is the Member's district. ALABAMA 1 Jerry L. Carl ................................................ Mobile 2 Barry Moore ................................................. Enterprise 3 Mike Rogers ................................................. Anniston 4 Robert B. Aderholt ....................................... Haleyville 5 Mo Brooks .................................................... Huntsville 6 Gary J. Palmer ............................................ Hoover 7 Terri A. Sewell ............................................. Birmingham ALASKA AT LARGE Don Young .................................................... Fort Yukon ARIZONA 1 Tom O'Halleran ........................................... Sedona 2 Ann Kirkpatrick .......................................... Tucson 3 Raúl M. Grijalva .......................................... Tucson 4 Paul A. Gosar ............................................... Prescott 5 Andy Biggs ................................................... Gilbert 6 David Schweikert ........................................ Fountain Hills 7 Ruben Gallego ............................................. Phoenix 8 Debbie Lesko ............................................... -

Thinking About Slavery at the College of William and Mary

William & Mary Bill of Rights Journal Volume 21 (2012-2013) Issue 4 Article 6 May 2013 Thinking About Slavery at the College of William and Mary Terry L. Meyers Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmborj Part of the Race, Ethnicity and Post-Colonial Studies Commons Repository Citation Terry L. Meyers, Thinking About Slavery at the College of William and Mary, 21 Wm. & Mary Bill Rts. J. 1215 (2013), https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmborj/vol21/iss4/6 Copyright c 2013 by the authors. This article is brought to you by the William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmborj THINKING ABOUT SLAVERY AT THE COLLEGE OF WILLIAM AND MARY Terry L. Meyers* I. POST-RECONSTRUCTION AND ANTE-BELLUM Distorting, eliding, falsifying . a university’s memory can be as tricky as a person’s. So it has been at the College of William and Mary, often in curious ways. For example, those delving into its history long overlooked the College’s eighteenth century plantation worked by slaves for ninety years to raise tobacco.1 Although it seems easy to understand that omission, it is harder to understand why the College’s 1760 affiliation with a school for black children2 was overlooked, or its president in 1807 being half-sympathetic to a black man seeking to sit in on science lectures,3 or its awarding an honorary degree to the famous English abolitionist Granville Sharp in 1791,4 all indications of forgotten anti-slavery thought at the College. To account for these memory lapses, we must look to a pivotal time in the late- nineteenth and early-twentieth century when the College, Williamsburg, and Virginia * Chancellor Professor of English, College of William and Mary, Williamsburg, Virginia, [email protected]. -

History of the United States Marine Corps

BOUGHT WITH THE INCOME FROM THE SAGE ENDOWMENT FUND THE GIFT OF Mtnvu W. Sage 1891 .AU.(^-7^-^-^- g..f..5.J4..^..Q: Cornell University Library VE23 .C71 1903 History of the United States marine corp 3 1924 030 896 488 olin The original of tiiis book is in tine Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924030896488 FRANKLIN WHARTON, Lieutenant-Colonel U. S. Marine Corps. Commandant March 7, 1804. DiEO September 1, 1818 : HISTORY OF THE United States Marine Corps RICHARD S. COIvIvUM:, Major U. S. M. C. NEW YORK L,. R. Hamersly Co. 1903. T Copyright, 1903, by L. R- HamERSLV Co. TO THE CITIZENS OF THE UNITED STATES THIS WORK IS RESPECTFULI,Y DEDICATED ; WITH A DESIRE THAT THE SERVICES OF THH UNITED STATES MARINE CORPS MAY BE INTEI,I,IGENTI,Y APPRECIATED, AND THAT THE NATION MAY RECOGNIZE THE DEBT IT OWES TO THE OFFICERS AND ENLISTED MEN, WHO, IN ALL THE TRYING TIMES IN OUR COUNTRY'S HISTORY HAVE NOBLY DONE THEIR DUTY. ' ' From the establishment of the Marine Corps to the present time it has constituted an integral part of the Navy, has been identified with it in all its achievements, ashore and afloat, and has continued to receive from its most distinguished commanders the expression of their appreciation of its effectiveness as a part of the Navy." —Report of House Committee on Naval Affairs ; Thir- ty-ninth Congress, Second Session. PREFACE. A CUSTOM has prevailed throughout the armies of Europe to keep regular record of the services and achievements of their regi- ments and corps. -

The Armistead Family. 1635-1910

r Digitized by tine Internet Arciiive in 2008 with funding from IVIicrosoft Corporation http://www.arcliive.org/details/armisteadfamily100garb l^fje Srmis;teab Jfamilp* 1 635-1 910. ^ BY Mrs. VIRGINIA ARMISTEAD GARBER RICHMOND, VIRGINIA. RICHMOND, VA. WHITTET & SHEPPERSON, PRINTERS, 1910. ' THE NEW YORK PUBLIC LIBRARY 703956 ASTOR, LENOX AND TILDtN FOUNDATIONS R 1915 L COPTRIGHT, J 910, BY Mrs. VIRGINIA ARMISTEAD GARBER, Richmond, Va. ; PREFACE. RECORD of the editor's branch of the Armistead family- A was begun in the summer of 1903, at the request of an elder brother, who came to Virginia for the purpose of collecting family data for his large family living in distant South- ern States. Airs. Sallie Nelson Robins, of the Virginia Historical Society, started the ball in motion when preparing his paper to join the Virginia Sons of the American Revolution. From this, the work has grown till the editor sends ''The Armistead Family'' to press, in sheer desperation at the endless chain she has started powerless to gather up the broken links that seem to spring up like dragon's teeth in her path. She feels that an explanation is due, for the biographical notes, detail descriptions, and traditions introduced in her own line; which was written when the record was intended solely for her family. Therefore, she craves in- dulgence for this personal element. Dr. Lyon G. Tyler's Armistead research in the William and Mary Quarterly is the backbone of the work, the use of which has been graciously accorded the editor. She is also indebted to Mr. Robert G.