Sample Chapter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

III. KNOWING Assistance .. ·I·

WHEN IS A STRANGERA CONSTRUCTIVETRUSTEE? 453 WHEN IS A STRANGER A CONSTRUCTIVE TRUSTEE? A CRITIQUE OF RECENT DECISIONS SUSAN BARKEHALL THOMAS• 1his articleexplores the conceptualdevelopment of Cet article explore le developpementconceptuel de third party liabilityfor participation in a breach of responsabilite civile dans la participation a fiduciary duty. 1he authorprovides a criticalanalysis l'inexecution d'une obligationfiduciaire. L 'auteur of thefoundations of third party liability in Canada fournit une analyse critique des fondations de la and chronicles the evolution of context-specific responsabilitecivile au Canada et decrit /'evolution liability tests. In particular, the testsfor the liability d'essais de responsabilites particulieres a une of banks and directorsare developed in their specific situation.Les essais de responsabilitedes banques el contexts. 1he author then provides a reasoned des adminislrateurssont particulierementdeveloppes critique of the Supreme Court of Canada's recent dans leur contexte precis. L 'auteurfournit ensulte trend towards context-independenttests. 1he author une critique raisonnee de la recente tendance de la concludes by arguing that the current approach is Cour supreme du Canada pour /es essais inadequateand results in an incoherentframework independantset particuliersa une situation.L 'auteur for the law of third party liability in Canada. conclut en pretendant que la demarche actuelle est inadequateet entraine un cadre incoherentpour la loi sur la responsabilitecivile au Canada. TABLE OF CONTENTS I. IN1R0DUCTION . • • • • . • . • . 453 II. KNOWING PARTICIPATION ......••...........•....•..... 457 A. BANKCASES . 457 B. APPLICATIONOF TIIE "PuT ON INQUIRY" TEST .....•...... 459 C. CONCEPTUALPROBLEMS Wl11I THE "PuT ON INQUIRY" TEST • . • . • • • . • . • . • . 463 D. CONCLUSIONSFROM PART II . 467 III. KNOWING AsSISTANCE .. ·I·............................ 467 A. THEAIR CANADA DECISION . • • • . • . 468 IV. -

Cambridge University Press 978-1-316-62194-3 — Equity and Trusts in Australia Michael Bryan , Vicki Vann , Susan Barkehall Thomas Index More Information INDEX

Cambridge University Press 978-1-316-62194-3 — Equity and Trusts in Australia Michael Bryan , Vicki Vann , Susan Barkehall Thomas Index More Information INDEX accounts of profits, 54–5, 169 limitation statutes, 84–5 remedies for. See remedies allowances, 57–8 unclean hands, 86–8, 168 for breach of trust breach of confidence, 197 beneficiaries, 206 ‘but for’ test, 65–6, 333 calculation of, 55–7 administration of trust and, acquiescence, 85–6 207 calculation of equitable as equitable defence to creditors’ rights and, 313–14 compensation, 60–1 breach of trust, 329–30 differences between fixed breach of fiduciary duty, overlap with laches, 85–6 and discretionary trusts 63–5 advancement for, 207 breach of trust, 61–3 presumption of, 357–9 ‘gift-over’ right, 208–9 calculation of equitable agency indemnification of trustees, damages trusts and, 210–11 311–13 causation standard, 65–6 aggravated damages, 68 interest, trustees’ right to common law adjustments to Anton Piller order, 39 impound, 314 quantum, 66–8 Aristotle, 4 investment of trust funds, categories of constructive trusts, assessment of equitable 297, 299 371 damages, 51 ‘list certainty’, 227 as remedy to proprietary in addition to injunction or sui juris, 278, 312 estoppel, 380–2 specific performance, 51 trust property and, 208 as restitutionary remedy in substitution for injunction trustees’ right to recover for unjust enrichment, or specific performance, overpayment from, 315 380–2 51–2 breach of confidence, 17–18, 47, Baumgartner constructive assignments 50, 68 trusts, 375–9 equitable property, 138–9 defences to. See defences to common intention, family future property, 137–8 breach of confidence property disputes and, gifts, 133–6 remedies for. -

CLAIMS AGAINST THIRD PARTIES Jeremy Bamford & Simon Passfield, Guildhall Chambers

CLAIMS AGAINST THIRD PARTIES Jeremy Bamford & Simon Passfield, Guildhall Chambers A. Introduction 1. This paper supports and provides the references for the Wonderland Ltd case study1 which will be considered during the seminar. 2. The aim of the case study is to explore claims which go beyond the usual fare of the office- holder’s statutory remedies by way of transactions at an undervalue, preference, s. 212 misfeasance claims, wrongful or fraudulent trading or transactions defrauding creditors. Instead we explore claims against third parties, where there has been a breach of the Companies Act and/or breach of fiduciary duty by directors, unlawful dividends being used as an example. B. Dividends 3. There are usually 3 potential grounds for challenging dividend payments: 3.1. the conventional technical claim made under the Companies legislation that dividends have not been paid out of profits available for that purpose and that the dividends have been paid in breach of the Companies legislation; 3.2. that the internal regulations of the company were breached and/or 3.3. breach of the common law maintenance of capital rule. We consider these in turn. B1 Part VIII CA 1985 4. In the case study the dividends were paid between 1 Sep 2007 and 1 March 2008. The relevant law is therefore Part VIII Companies Act 1985 (ss. 263 – 281 CA 1985)2. 5. A distribution of a company’s assets (which includes a dividend) can only be made out of profits available for the purpose (s. 263(1) CA 1985)3 being its accumulated, realised profits, so far as not previously utilised by distribution or capitalisation, less its accumulated, realised losses, so far as not previously written off in a reduction or reorganisation of capital duly made (s. -

ERISA Fiduciaries Cross-Dress Legal Remedies As Equitable

Liberty University Law Review Volume 3 Issue 1 Article 6 March 2009 Not-So-Equitable Liens: ERISA Fiduciaries Cross-Dress Legal Remedies as Equitable Brandon S. Osterbind Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/lu_law_review Recommended Citation Osterbind, Brandon S. (2009) "Not-So-Equitable Liens: ERISA Fiduciaries Cross-Dress Legal Remedies as Equitable," Liberty University Law Review: Vol. 3 : Iss. 1 , Article 6. Available at: https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/lu_law_review/vol3/iss1/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Liberty University School of Law at Scholars Crossing. It has been accepted for inclusion in Liberty University Law Review by an authorized editor of Scholars Crossing. For more information, please contact [email protected]. COMMENT NOT-SO-EQUITABLE LIENS: ERISA FIDUCIARIES CROSS-DRESS LEGAL REMEDIES AS EQUITABLE Brandon S. Osterbindt I. INTRODUCTION The Supreme Court of the United States has the unfortunate role of finding the law' and determining what it is.2 While this may seem to be a simple and intuitive task, interpreting the Employee Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA) 3 inevitably results in a "descent into a Serbonian bog wherein judges are forced to don logical blinders and split ' the linguistic atom to decide even the most routine cases. The average personal injury plaintiff does not appreciate the nature of the litigation' that results in the achievement of the plaintiff's ultimate goal: t Brandon S. Osterbind graduated from Liberty University School of Law in May 2008 and is a judicial clerk to the Honorable William G. Petty of the Court of Appeals of Virginia. -

Remedies: Appropriate Equitable Relief Under ERISA After Montanile

ACI’s 13th National Forum on ERISA Litigation October 27-28, 2016 Remedies: Appropriate Equitable Relief Under ERISA After Montanile R. Joseph Barton Eric G. Serron Stephen Rosenberg Partner Partner Partner Cohen Milstein Sellers & Toll PLLC Steptoe & Johnson LLP The Wagner Law Group Tweeting about this conference? #ERISA Hot Topics in Remedies •What is “appropriate equitable relief” under ERISA § 502(a)(3)? •Claims against participants & non-fiduciaries •Claims against fiduciaries for individual recovery #ERISA ERISA § 502(a)(3) “a civil action may be brought by a participant, beneficiary, or fiduciary (A) to enjoin any act or practice which violates any provision of this title or the terms of the Plan, or (B) to obtain other appropriate equitable relief (i) to redress [] violations [of ERISA or the terms of the plan] or (ii) to enforce any provisions of this subchapter or the terms of the plan.” #ERISA Claims Against Participants and Non- Fiduciaries • Montanile v. Bd. Of Trustees of Nat. Elevator Indus. Health Benefit Plan, 136 S.Ct. 651 (2016): • 502(a)(3) does not permit equitable lien by agreement against beneficiary’s general assets. #ERISA Montanile continued • ERISA health plan paid for Montanile’s medical expenses after he was hit by drunk driver. Montanile received a $500k settlement from drunk driver. • Plan has subrogation clause and health plan sought reimbursement; attorney refused the request and paid the settlement to Montanile. • Plan sued under 502(a)(3) for equitable lien. • Held: Where funds are completely dissipated on non- traceable items, no 502(a)(3) suit allowed to attach to participant’s general assets. -

Beyond Unconscionability: the Case for Using "Knowing Assent" As the Basis for Analyzing Unbargained-For Terms in Standard Form Contracts

Beyond Unconscionability: The Case for Using "Knowing Assent" as the Basis for Analyzing Unbargained-for Terms in Standard Form Contracts Edith R. Warkentinet I. INTRODUCTION People who sign standard form contracts' rarely read them.2 Coun- sel for one party (or one industry) generally prepare standard form con- tracts for repetitive use in consecutive transactions.3 The party who has t Professor of Law, Western State University College of Law, Fullerton, California. The author thanks Western State for its generous research support, Western State colleague Professor Phil Merkel for his willingness to read this on two different occasions and his terrifically helpful com- ments, Whittier Law School Professor Patricia Leary for her insightful comments, and Professor Andrea Funk for help with early drafts. 1. Friedrich Kessler, in a pioneering work on contracts of adhesion, described the origins of standard form contracts: "The development of large scale enterprise with its mass production and mass distribution made a new type of contract inevitable-the standardized mass contract. A stan- dardized contract, once its contents have been formulated by a business firm, is used in every bar- gain dealing with the same product or service .... " Friedrich Kessler, Contracts of Adhesion- Some Thoughts About Freedom of Contract, 43 COLUM. L. REV. 628, 631-32 (1943). 2. Professor Woodward offers an excellent explanation: Real assent to any given term in a form contract, including a merger clause, depends on how "rational" it is for the non-drafter (consumer and non-consumer alike) to attempt to understand what is in the form. This, in turn, is primarily a function of two observable facts: (1) the complexity and obscurity of the term in question and (2) the size of the un- derlying transaction. -

Tracing Is a Process Not a Remedy

Tracing - Scenario 1(b): Trustee Mixes Trust Money - Tracing is a process not a remedy. With His Own In His Account, subsequently - It allows us to identify a new asset as the purchases property with some money in the substitute for the old (Foskett v McKeown). account, then exhausts remaining money. - Tracing follows the value of the beneficiaries - SOLUTION: Re Oatway: We get an property, not the property itself (following). exception to the rule in Hallett’s estate: if the wrongdoer purchased assets which still exist, Distinguishing Tracing; Following & Claiming then it is presumed that he did so with the - Following is the process of following the same stolen money and the beneficiaries are asset as it moves from hand to hand. entitled to the assets. - Claiming refers to the process of recovering property, or the substitute for that property (This - Scenario 1(c): Trustee Mixes Money With His refers to the Barnes v Addy; knowing receipt, Own In His Account, and makes payment in knowing assistance doctrine - MUST and out of that account. CONSIDER THIS AFTER TRACING). - SOLUTION: Lofts v McDonald: Lowest Intermediate Balance Rule: trust cannot claim more than the lowest intermediate balance Tracing at Common Law - credited to the wrongdoer’s bank account Tracing is not unique to equity, however at CL it - If it went up from the lowest point, that is requires that the property you are tracing is not the trust’s money. identifiable, giving rise to problems with banks. - - Although you are deprived of a proprietary Equity has developed rules for identifying remedy, not personal remedies. -

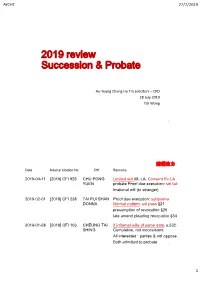

2019 Review Succession & Probate

AYCHT 27/7/2019 2019 review Succession & Probate Au‐Yeung Cheng Ho Tin solicitors –CPD 28 July 2019 Tak Wong 1 遺囑效力 Date Neutral Citation No Pltf Remarks 2019-04-11 [2019] CFI 925 CHU PONG Limited will 08, LA. Consent Rv LA YUEN probate Proof due execution: sol fail Irrational will (to stranger) 2019-02-01 [2019] CFI 238 TAI PUI SHAN Proof due execution: subpoena. DONNA Normal pattern. sol pass §21 presumption of revocation §26 late amend pleading revocation §34 2019-01-28 [2019] CFI 103 CHEUNG TAI 2 informal wills of same date. s.5(2) SHING Cumulative, not inconsistent. All interested : parties & not oppose. Both admitted to probate. 2 1 AYCHT 27/7/2019 遺囑效力 Date Neutral Citation No Pltf Remarks 2018-12-19 [2018] CFA 61 CHOY PO B v G evidence 3 limbs T/C.gap§11 CHUN fact-specific. No proper basis will instruction §18. will invalid 2019-04-18 [2019] CA 452 MOK HING Same B v G 3 limbs T/C. CHUNG fact-specific Yes proper basis. Choy Po Chun distinguished. Will instruction direct / rational Sol > sol firm. Will valid. 3 親屬關係 Date Neutral Citation No Pltf Remarks 2018-08-08 [2018] CA 491 LI CHEONG Natural dau, 1. DNA 2. copy B/C, rolled-up hearing directions 2018-10-18 [2018] CA 719 LI CHEONG Probate action in rem nature, O.15 r.13A, intended intervener, dismiss 2014-07-03 MOK HING CCL:spinster 1.no adopt §89 2.yes CHUNG i-tze 3.yes IEO s2(2)(c) 4.DWAE案 2018-10-19 [2018] CA 713 MOK HING CCL adoption v i-tze, apply to file CHUNG obituary notice, Ladd, dismiss 2019-04-18 [2019] CA 452 MOK HING CCL no formalities (adoption/i-tze) CHUNG §52, all 7 appeal grounds no merit. -

An Economic Analysis of Law Versus Equity

AN ECONOMIC ANALYSIS OF LAW VERSUS EQUITY Henry E. Smith* October 22, 2010 I. INTRODUCTION Like “property,” the terms “equity” and “equitable” are hardly missing from legal discourse. They can refer to fairness, a type of jurisdiction, types of remedies and defenses, an owner’s stake in an asset subject to a security interest and other ownership interests, as well as a set of maxims, among other things. These uses of “equity” and “equitable” all trace back to courts of equity, which, with some exceptions, ceased to exist as separate courts or even as a distinct form of jurisdiction by the early twentieth century.1 So the term “equity” might seem to be an etymological curiosity. This paper challenges that view. It argues that the notion of equity is functionally motivated and can be given an economic analysis under which it makes sense to have a separate decision making mode that is loosely identified with historical equity jurisdiction and jurisprudence. * Fessenden Professor of Law, Harvard Law School. Email: [email protected]. I would like to thank Bob Ellickson; Bruce Johnsen; Louis Kaplow; Steve Spitz; and audiences at the Fourth Annual Triangle Law and Economics Conference, Duke Law School; the George Mason University School of Law, Robert A. Levy Fellows Workshop in Law & Liberty; the Harvard Law School Law and Economics Seminar; the Workshop on Property Law and Theory, New York University School of Law; the University of Notre Dame Law School Faculty Workshop; the International Society for New Institutional Economics, 14th Annual Conference, University of Stirling, Scotland; and the Carl Jacob Arnholm Memorial Lecture, Institute of Private Law, University of Oslo Faculty of Law. -

Imagereal Capture

EQUITABLE ADEMPTION WITHIN THE FAMILY Introduction A parent's generosity towards a child may often cause a family dispute. In particular, if one child has received a substantial gift of money or other material benefits during the parent's lifetime, other children will often look to the parent's will, and may invoke the law with regard to its provisions, in order to redress what they perceive as an injustice to themselves. A parent, it is said, has a duty to treat children equally. This is not, of course, in any sense a legal duty; but the law nevertheless recognizes that in some cir- cumstances a child benefited by a parent should account for that benefit to his or her brothers and sisters. The mechanism available for this purpose is the equitable doc- trine of ademption,' otherwise known as the doctrine of satisfac- *R.A , LI,.B., LL.M. Senior Lecturer in Law, University of Western Australia 1. The word "ademption" in its legal usage applies to three quite different situations: first, where the subject-matter of a specific legacy is disposed of by a testator inter uluos or otherwise ceases to exist so that it forms no part of his estate at death; second, where a legacy is glven for a particular purpose and is followed by a gift tnter u~uosby the testator to the legatee for substantially the same purpose; third, where a portion given Inter L'ZUOS is regarded in equity as an adernption of a prior testamentary portion. This article is concerned only with the third of these situations. -

Asset Tracing in the British Virgin Islands

Article Asset Tracing in the British Virgin Islands In this article, we will discuss some of the tools available to a party in the British Virgin Islands to seek to recover property, or proceeds of property, which have been misappropriated. It is not surprising that in some cases, the identity of the wrongdoer or the whereabouts of the misappropriated property is unknown. Against that background, it is worth noting that while a BVI, and whether there has been any past judgment which company incorporated in the BVI is required to maintain may shed light on assets held by the company. In addition, certain records at the office of its registered agent (such as upon application the BVI Land Registry can provide certain its memorandum and articles of association, register of details regarding the owner of BVI land or real estate. directors, register of members, minutes of members’ and However, this requires the applicant to first be able to directors’ meetings and copies of resolutions), there is no identify the location or owner of the land. A party may also right for the public to inspect such records. Indeed, obtain certain information regarding vessels registered under confidentiality of corporate documents and information is a BVI flag from the BVI Ship Registry. one of the key attractions of incorporating a company in the BVI. BVI companies are not generally required to maintain or What is “tracing”? file statutory accounts, or meet any particular set of international accounting standards. Under section 98 of the Tracing consists of a series of rules developed by equity to BVI Business Companies Act 2004, all that a company is deal with situations where assets have been required to maintain are records “sufficient to show and misappropriated and the wrongdoer is not in a position to explain the company’s transactions” and which “will, at any compensate, or money compensation is not adequate. -

“Clean Hands” Doctrine

Announcing the “Clean Hands” Doctrine T. Leigh Anenson, J.D., LL.M, Ph.D.* This Article offers an analysis of the “clean hands” doctrine (unclean hands), a defense that traditionally bars the equitable relief otherwise available in litigation. The doctrine spans every conceivable controversy and effectively eliminates rights. A number of state and federal courts no longer restrict unclean hands to equitable remedies or preserve the substantive version of the defense. It has also been assimilated into statutory law. The defense is additionally reproducing and multiplying into more distinctive doctrines, thus magnifying its impact. Despite its approval in the courts, the equitable defense of unclean hands has been largely disregarded or simply disparaged since the last century. Prior research on unclean hands divided the defense into topical areas of the law. Consistent with this approach, the conclusion reached was that it lacked cohesion and shared properties. This study sees things differently. It offers a common language to help avoid compartmentalization along with a unified framework to provide a more precise way of understanding the defense. Advancing an overarching theory and structure of the defense should better clarify not only when the doctrine should be allowed, but also why it may be applied differently in different circumstances. TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ................................................................................. 1829 I. PHILOSOPHY OF EQUITY AND UNCLEAN HANDS ...................... 1837 * Copyright © 2018 T. Leigh Anenson. Professor of Business Law, University of Maryland; Associate Director, Center for the Study of Business Ethics, Regulation, and Crime; Of Counsel, Reminger Co., L.P.A; [email protected]. Thanks to the participants in the Discussion Group on the Law of Equity at the 2017 Southeastern Association of Law Schools Annual Conference, the 2017 International Academy of Legal Studies in Business Annual Conference, and the 2018 Pacific Southwest Academy of Legal Studies in Business Annual Conference.