III. KNOWING Assistance .. ·I·

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cambridge University Press 978-1-316-62194-3 — Equity and Trusts in Australia Michael Bryan , Vicki Vann , Susan Barkehall Thomas Index More Information INDEX

Cambridge University Press 978-1-316-62194-3 — Equity and Trusts in Australia Michael Bryan , Vicki Vann , Susan Barkehall Thomas Index More Information INDEX accounts of profits, 54–5, 169 limitation statutes, 84–5 remedies for. See remedies allowances, 57–8 unclean hands, 86–8, 168 for breach of trust breach of confidence, 197 beneficiaries, 206 ‘but for’ test, 65–6, 333 calculation of, 55–7 administration of trust and, acquiescence, 85–6 207 calculation of equitable as equitable defence to creditors’ rights and, 313–14 compensation, 60–1 breach of trust, 329–30 differences between fixed breach of fiduciary duty, overlap with laches, 85–6 and discretionary trusts 63–5 advancement for, 207 breach of trust, 61–3 presumption of, 357–9 ‘gift-over’ right, 208–9 calculation of equitable agency indemnification of trustees, damages trusts and, 210–11 311–13 causation standard, 65–6 aggravated damages, 68 interest, trustees’ right to common law adjustments to Anton Piller order, 39 impound, 314 quantum, 66–8 Aristotle, 4 investment of trust funds, categories of constructive trusts, assessment of equitable 297, 299 371 damages, 51 ‘list certainty’, 227 as remedy to proprietary in addition to injunction or sui juris, 278, 312 estoppel, 380–2 specific performance, 51 trust property and, 208 as restitutionary remedy in substitution for injunction trustees’ right to recover for unjust enrichment, or specific performance, overpayment from, 315 380–2 51–2 breach of confidence, 17–18, 47, Baumgartner constructive assignments 50, 68 trusts, 375–9 equitable property, 138–9 defences to. See defences to common intention, family future property, 137–8 breach of confidence property disputes and, gifts, 133–6 remedies for. -

CLAIMS AGAINST THIRD PARTIES Jeremy Bamford & Simon Passfield, Guildhall Chambers

CLAIMS AGAINST THIRD PARTIES Jeremy Bamford & Simon Passfield, Guildhall Chambers A. Introduction 1. This paper supports and provides the references for the Wonderland Ltd case study1 which will be considered during the seminar. 2. The aim of the case study is to explore claims which go beyond the usual fare of the office- holder’s statutory remedies by way of transactions at an undervalue, preference, s. 212 misfeasance claims, wrongful or fraudulent trading or transactions defrauding creditors. Instead we explore claims against third parties, where there has been a breach of the Companies Act and/or breach of fiduciary duty by directors, unlawful dividends being used as an example. B. Dividends 3. There are usually 3 potential grounds for challenging dividend payments: 3.1. the conventional technical claim made under the Companies legislation that dividends have not been paid out of profits available for that purpose and that the dividends have been paid in breach of the Companies legislation; 3.2. that the internal regulations of the company were breached and/or 3.3. breach of the common law maintenance of capital rule. We consider these in turn. B1 Part VIII CA 1985 4. In the case study the dividends were paid between 1 Sep 2007 and 1 March 2008. The relevant law is therefore Part VIII Companies Act 1985 (ss. 263 – 281 CA 1985)2. 5. A distribution of a company’s assets (which includes a dividend) can only be made out of profits available for the purpose (s. 263(1) CA 1985)3 being its accumulated, realised profits, so far as not previously utilised by distribution or capitalisation, less its accumulated, realised losses, so far as not previously written off in a reduction or reorganisation of capital duly made (s. -

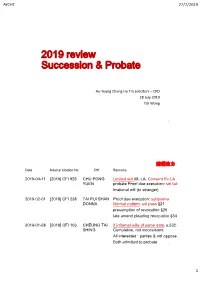

2019 Review Succession & Probate

AYCHT 27/7/2019 2019 review Succession & Probate Au‐Yeung Cheng Ho Tin solicitors –CPD 28 July 2019 Tak Wong 1 遺囑效力 Date Neutral Citation No Pltf Remarks 2019-04-11 [2019] CFI 925 CHU PONG Limited will 08, LA. Consent Rv LA YUEN probate Proof due execution: sol fail Irrational will (to stranger) 2019-02-01 [2019] CFI 238 TAI PUI SHAN Proof due execution: subpoena. DONNA Normal pattern. sol pass §21 presumption of revocation §26 late amend pleading revocation §34 2019-01-28 [2019] CFI 103 CHEUNG TAI 2 informal wills of same date. s.5(2) SHING Cumulative, not inconsistent. All interested : parties & not oppose. Both admitted to probate. 2 1 AYCHT 27/7/2019 遺囑效力 Date Neutral Citation No Pltf Remarks 2018-12-19 [2018] CFA 61 CHOY PO B v G evidence 3 limbs T/C.gap§11 CHUN fact-specific. No proper basis will instruction §18. will invalid 2019-04-18 [2019] CA 452 MOK HING Same B v G 3 limbs T/C. CHUNG fact-specific Yes proper basis. Choy Po Chun distinguished. Will instruction direct / rational Sol > sol firm. Will valid. 3 親屬關係 Date Neutral Citation No Pltf Remarks 2018-08-08 [2018] CA 491 LI CHEONG Natural dau, 1. DNA 2. copy B/C, rolled-up hearing directions 2018-10-18 [2018] CA 719 LI CHEONG Probate action in rem nature, O.15 r.13A, intended intervener, dismiss 2014-07-03 MOK HING CCL:spinster 1.no adopt §89 2.yes CHUNG i-tze 3.yes IEO s2(2)(c) 4.DWAE案 2018-10-19 [2018] CA 713 MOK HING CCL adoption v i-tze, apply to file CHUNG obituary notice, Ladd, dismiss 2019-04-18 [2019] CA 452 MOK HING CCL no formalities (adoption/i-tze) CHUNG §52, all 7 appeal grounds no merit. -

Unconscionability As an Underlying Concept in Equity

THE DENNING LAW JOURNAL UNCONSCIONABILITY AS A UNIFYING CONCEPT IN EQUITY Mark Pawlowski* ABSTRACT This article seeks to examine the extent to which a unified concept of unconscionability can be used to rationalise related doctrines of equity, in particular, in the areas of (1) unconscionable bargains, undue influence and duress (2) proprietary estoppel (3) knowing receipt liability and (4) relief against forfeitures. The conclusion is that such a process of amalgamation may provide a principled doctrinal basis for equity’s intervention which has already found favour in the English courts. INTRODUCTION A recent discernible trend in equity has been the willingness of the English courts to adopt a broader-based doctrine of unconscionability as underlying proprietary estoppel claims and the personal liability of a stranger to a trust who has knowingly received trust property in breach of trust. The decisions in Gillett v Holt,1 Jennings v Rice2 and Campbell v Griffin3 in the context of proprietary estoppel and Bank of Credit and Commerce International (Overseas) Ltd v Akindele4 on the subject of receipt liability, demonstrate the judiciary’s growing recognition that the concept of unconscionability provides a useful mechanism for affording equitable relief against the strict insistence on legal rights or unfair and oppressive conduct. This, in turn, prompts the question whether there are other areas which would benefit from a rationalisation of principles under the one umbrella of unconscionability. The process of amalgamation, it is submitted, would be particularly useful in areas where there are currently several related (but distinct) doctrines operating together so as to give rise to confusion and overlap in the same field of law. -

Unit 5 – Equity and Trusts Suggested Answers - January 2013

LEVEL 6 - UNIT 5 – EQUITY AND TRUSTS SUGGESTED ANSWERS - JANUARY 2013 Note to Candidates and Tutors: The purpose of the suggested answers is to provide students and tutors with guidance as to the key points students should have included in their answers to the January 2013 examinations. The suggested answers set out a response that a good (merit/distinction) candidate would have provided. The suggested answers do not for all questions set out all the points which students may have included in their responses to the questions. Students will have received credit, where applicable, for other points not addressed by the suggested answers. Students and tutors should review the suggested answers in conjunction with the question papers and the Chief Examiners’ reports which provide feedback on student performance in the examination. SECTION A Question 1 This essay will examine the general characteristics of equitable remedies before examining each remedy in turn to analyse whether they are in fact strict and of limited flexibility as the question suggests. The best way to examine the general characteristics of equitable remedies is to draw comparisons with the common law. Equitable remedies are, of course discretionary, whereas the common law remedy of damages is available as of right. This does not mean that the court has absolute discretion, there are clear principles which govern the grant of equitable remedies. Equitable remedies are granted where the common law remedies would be inadequate or where the common law remedies are not available because the right is exclusively equitable. One of the key characteristics of equitable remedies is of course that they act in personam. -

KNOWING RECEIPT of FRAUDULENT FUNDS & KNOWING ASSISTANCE in BREACH of TRUST in ESTATES & TRUSTS by Justin W

KNOWING RECEIPT OF FRAUDULENT FUNDS & KNOWING ASSISTANCE IN BREACH OF TRUST IN ESTATES & TRUSTS by Justin W. de Vries1 INTRODUCTION In equity, a third party who receives money from a fiduciary, in breach of the fiduciary’s trust obligations to a beneficiary, is liable in a personal action brought by the beneficiary.2 The beneficiary does not need to show that the third party recipient committed fraud or was dishonest in acquiring the funds. The beneficiary must simply show that the third party recipient knew, or should have known, that the trustees were acting in breach of the terms of the trust when they made the transfer.3 In other words, the beneficiary must show that the third party knowingly participated in the fraud. The equitable basis for this action is the principle of unjust enrichment: there is no reason that the third party recipient should be enriched by the misappropriated property at the expense of the beneficiary. Where this occurs, the third party recipient may be compelled to return the misappropriated funds.4 The ability to pursue a third party via the claim of unjust enrichment is a useful tool for wronged beneficiaries. It is especially important where the fraudulent trustee has disappeared or died and restitution cannot be obtained from him. There are, of course, defences to the claim of unjust enrichment. Where the third party recipient does not receive notice of the trust, nor could he have otherwise known about the trust, then the 1 Justin de Vries can be reached at 416-640-2757 (Toronto) or 905-844-0900 (Oakville) or by email at [email protected]. -

STRANGER LIABILITY: a QUESTION of CONSCIENCE PROPERTY OR STANDARDS? by Kerrell Ma* PART ONE Introduction Trustees Have Some Onerous Duties

STRANGER LIABILITY: A QUESTION OF CONSCIENCE PROPERTY OR STANDARDS? by Kerrell Ma* PART ONE Introduction Trustees have some onerous duties. Their principle duty is to discharge themselves by accounting to their beneficiaries for the trust property. That duty or a duty akin to it should not be imposed lightly on any persons other than an express trustee, unless those persons' actions in relation to the trust property are such that they ought to attract such a duty. Furthermore, before equity imposes a liability on persons other than an express trustee (referred to as strangers to the trust) for participating in a breach of trust or breach of fiduciary duty there should be a clear reason for so doing. Is it because of: 1.the unconscionable behaviour of the stranger in relation to the property; or 2. the stranger's fault in not realising that the dealing with the property constitutes a breach of trust or fiduciary duty or that any assistance rendered enables a breach to be committed; or 3. the stranger's notice in respect of the breach; or 4. the stranger's unjust enrichment by receipt of property, or for more than one of these reasons? Judges and academics cannot agree on the underlying basis for the obligations imposed on strangers for receipt of property received in breach of trust or in breach of fiduciary duties or for the rendering of assistance in such breaches.1 It is then no small wonder that with the offering of different paths, the law in relation to constructive trust liability for strangers to trusts is in disarray. -

The End of Knowing Receipt

The End of Knowing Receipt Robert Chambers* Introduction The law regarding personal liability for knowing receipt of assets transferred in breach of trust or fiduciary duty has received an extraordinary amount of academic and judicial attention over the past 30 years.1 Yet despite this flurry of attention (or perhaps because of it), the law in this area remains in a muddled and unsatisfactory state. There are disagreements over the various elements of the cause of action, which stem from a lack of consensus over the basic nature of the liability: is it a form of restitution of benefits received, compensation for losses caused, or something else? Part of the problem is the language used in this area. Words and phrases, such as “the first limb of Barnes v Addy”, “liability to account as a constructive trustee”, or even “knowing receipt” itself, tend to obscure more than they reveal. While complex concepts do require specialist terminology, it is possible to speak plainly in this area and reveal more. A frequently quoted statement of the essential elements of liability for knowing receipt was by Hoffmann LJ in El Ajou v Dollar Land Holdings plc:2 “This is a claim to enforce a constructive trust on the basis of knowing receipt. For this purpose the plaintiff must show, first, a disposal of his assets in breach of fiduciary duty; secondly, the beneficial receipt by the defendant of assets which are traceable as representing the assets of the plaintiff; and thirdly, knowledge on the part of the defendant that the assets he received are traceable to a breach of fiduciary duty.” While succinct, each part of this statement raises questions about the nature and ambit of knowing receipt. -

Restitution from Banks Jonathon P

ABSTRACT Restitution From Banks Jonathon P. Moore Christ Church, Oxford Submitted to the Board of the Faculty of Law, University of Oxford, for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Hilary Term 2000. This study analyses certain controversial issues commonly arising when a claim for restitution is brought against a bank. Chapter 1 considers the equitable claim traditionally labelled ‘knowing receipt’. Three issues are discussed: (i) the basis in principle of the claim for ‘knowing receipt’; (ii) whether the claim requires proof of fault on the part of the recipient; and (iii) whether the claim can be brought in relation to the receipt by a bank of a mortgage or guarantee offered to the bank in breach of trust or fiduciary duty. The conclusions are (i) that ‘knowing receipt’ is often a claim in unjust enrichment, though the dishonest recipient will also be liable for an equitable wrong; (ii) that when the unjust enrichment version of ‘knowing receipt’ is in issue, the claim should be one of strict liability; and (iii) a claim in unjust enrichment can be brought against a bank to defeat its interest in a mortgage or guarantee offered in breach of trust. Chapters 2 to 4 concern a concept within the law of unjust enrichment that has come to be called ministerial receipt. A ministerial receipt is a receipt of money or property by an agent on behalf of his or her principal. Banks often receive money as agents on behalf of account holders. Chapters 2 and 3 analyse that concept as it is dealt with at common law and in equity respectively. -

Claims Against Third-Party Recipients of Trust Property

Cambridge Law Journal, 76(2), July 2017, pp. 399–429 © Cambridge Law Journal and Contributors 2017. This is an Open Access article, distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike licence (http:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/), which permits non-commercial re-use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the same Creative Commons licence is included and the original work is properly cited. The written permission of Cambridge University Press must be obtained for commercial re-use. doi:10.1017/S0008197317000423 CLAIMS AGAINST THIRD-PARTY RECIPIENTS OF TRUST PROPERTY DAVID SALMONS* ABSTRACT. This article argues that claims to recover trust property from third parties arise in response to a trustee’s duty to preserve identifiable property, and that unjust enrichment is incompatible with such claims. First, unjust enrichment can only assist with the recovery of abstract wealth and so it does not assist in the recovery of specific property. Second, it is difficult to identify a convincing justification for introducing unjust enrich- ment. Third, it will work to the detriment of innocent recipients. The article goes on to show how Re Diplock supports this analysis, by demonstrating that no duty of preservation had been breached and that a proprietary claim should not have been available in that case. The simple conclusion is that claims to recover specific property and claims for unjust enrichment should be seen as mutually exclusive. KEYWORDS: trusts, third parties, proprietary claims, knowing receipt, res- titution, unjust enrichment, Re Diplock. I. INTRODUCTION According to orthodox trust principles, where property is transferred in breach of trust, a beneficiary can either bring a proprietary claim to recover the property or a personal claim against a knowing recipient of the trust property (hereinafter, the combination of these two claims will be referred to as the “equitable regime”). -

The Meaning and Significance of Conscience in Private Law

THE MEANING AND SIGNIFICANCE OF CONSCIENCE IN PRIVATE LAW ABSTRACT AND KEY WORDS This article seeks to explain the meaninG and siGnificance of the lanGuage of conscience in private law. In doing so, it draws on the etymoloGy and ordinary meaninG of conscience and recent work relatinG to the distinction between obliGations and liabilities. It arGues that the lanGuage of conscience plays a siGnificant, albeit hiGhly General, explanatory role in the context of eQuitable obliGations, such as the obliGation of confidence, trust obliGations and the obliGations of knowinG recipients. The lanGuage of conscience has less explanatory force in the context of primary liabilities, such as the liability to make restitution or rescind a contract in response to a defective transfer, and various forms of estoppel. The article arGues further that the indiscriminate use of the lanGuage of conscience in the context of both eQuitable obliGations and primary liabilities can generate confusion and uncertainty. Nevertheless, if due attention is paid to its explanatory limits and the context in which it is used, its continued presence in private law is valuable. Key Words: conscience; unconscionability; eQuity; trusts; restitution; contract; estoppel WORD COUNT Text: 9,787 Footnotes: 3,184 1 THE MEANING AND SIGNIFICANCE OF CONSCIENCE IN PRIVATE LAW I. INTRODUCTION The invocation of the lanGuage of conscience in private law is controversial. On the one hand, the courts freQuently use the lanGuage of conscience and unconscionability1 in a wide ranGe of common law and eQuitable doctrines.2 On the other hand, critics arGue that such lanGuage is vague and likely to Give rise to leGal uncertainty and the unacceptable conflation of law and morality.3 This article seeks to explain the meaninG and siGnificance of the lanGuage of conscience in EnGlish private law doctrine. -

Remodelling Knowing Receipt As a Gains-Based Wrong

Whayman D. Remodelling Knowing Receipt as a Gains-Based Wrong. Journal of Business Law 2016, 7, 565-588. Copyright: This is a pre-copyedited, author-produced version of an article accepted for publication in Journal of Business Law following peer review. The definitive published version is available online on Westlaw UK or from Thomson Reuters DocDel service. Date deposited: 12/09/2016 Embargo release date: 01 September 2017 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported License Newcastle University ePrints - eprint.ncl.ac.uk Remodelling Knowing Receipt as a Gains-Based Wrong Derek Whayman* [email protected] Newcastle Law School Newcastle University 21–24 Windsor Terrace Newcastle upon Tyne NE1 7RU Abstract This article analyses the nature of knowing receipt. It finds its previous characterisations as a form of unjust enrichment or trustee-like liability wanting in the face of newer authority and complex commercial situations. It argues that knowing receipt is a gains-based profit- disgorging wrong and this best describes its remedies. 1. Introduction The action in knowing receipt is an invaluable tool in the armoury of the claimant who wants to recover misapplied trust or company property from a stranger to the trust or fiduciary relation. It might be that the trustee or fiduciary is a man of straw or has disappeared or simply that the recipient is easier to sue. Then, provided the claimant can show that the recipient beneficially received property traceable to a breach of trust of fiduciary duty with cognisance of that breach, a personal claim exists.1 However, the precise nature of knowing receipt and particularly how this translates into the remedy available – namely quantum – is contested.