'Dishonest and Fraudulent Design' Requirement in Accessorial Liability

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Equitable Allowances Or Restitutionary Measures for Dishonest Assistance and Knowing Receipt

Whayman D. Equitable allowances or restitutionary measures for dishonest assistance and knowing receipt. Northern Ireland Legal Quarterly 2017, 68(2), 181–202. Copyright: © Queen's University School of Law. This is the final version of an article published in Northern Ireland Legal Quarterly by Queen's University School of Law. DOI link to article: https://nilq.qub.ac.uk/index.php/nilq/article/view/34 Date deposited: 10/08/2017 Newcastle University ePrints - eprint.ncl.ac.uk NILQ 68(2): 181–202 Equitable allowances or restitutionary measures for dishonest assistance and knowing receipt DEREK WHAYMAN * Lecturer in Law, Newcastle University Abstract This article considers the credit given to dishonest assistants and knowing recipients in claims for disgorgement, with greater focus on dishonest assistance. Traditionally, equity has awarded a parsimonious ‘just allowance’ for work and skill. The language of causation in Novoship (UK) Ltd v Mikhaylyuk [2014] EWCA Civ 908 suggests a more generous restitutionary approach which is at odds with the justification given: prophylaxis. This tension makes the law incoherent. Moreover, the bar to full disgorgement has been set too high, such that the remedy is unavailable in practice. Therefore, even if the restitutionary approach is affirmed, it must be revised. Keywords: disgorgement; equitable allowances; remoteness of gain; dishonest assistance; knowing receipt. isgorgement in equity has become more widely available. It is familiar as against a fiduciary where the profits of the defaulting fiduciary’s efforts are appropriated to the pDrincipal, seen in cases such as Boardman v Phipps .1 In Novoship (UK) Ltd v Mikhaylyuk , the Court of Appeal held that disgorgement is available in principle against accessories (meaning dishonest assistants and knowing recipients) to a breach of fiduciary duty. -

III. KNOWING Assistance .. ·I·

WHEN IS A STRANGERA CONSTRUCTIVETRUSTEE? 453 WHEN IS A STRANGER A CONSTRUCTIVE TRUSTEE? A CRITIQUE OF RECENT DECISIONS SUSAN BARKEHALL THOMAS• 1his articleexplores the conceptualdevelopment of Cet article explore le developpementconceptuel de third party liabilityfor participation in a breach of responsabilite civile dans la participation a fiduciary duty. 1he authorprovides a criticalanalysis l'inexecution d'une obligationfiduciaire. L 'auteur of thefoundations of third party liability in Canada fournit une analyse critique des fondations de la and chronicles the evolution of context-specific responsabilitecivile au Canada et decrit /'evolution liability tests. In particular, the testsfor the liability d'essais de responsabilites particulieres a une of banks and directorsare developed in their specific situation.Les essais de responsabilitedes banques el contexts. 1he author then provides a reasoned des adminislrateurssont particulierementdeveloppes critique of the Supreme Court of Canada's recent dans leur contexte precis. L 'auteurfournit ensulte trend towards context-independenttests. 1he author une critique raisonnee de la recente tendance de la concludes by arguing that the current approach is Cour supreme du Canada pour /es essais inadequateand results in an incoherentframework independantset particuliersa une situation.L 'auteur for the law of third party liability in Canada. conclut en pretendant que la demarche actuelle est inadequateet entraine un cadre incoherentpour la loi sur la responsabilitecivile au Canada. TABLE OF CONTENTS I. IN1R0DUCTION . • • • • . • . • . 453 II. KNOWING PARTICIPATION ......••...........•....•..... 457 A. BANKCASES . 457 B. APPLICATIONOF TIIE "PuT ON INQUIRY" TEST .....•...... 459 C. CONCEPTUALPROBLEMS Wl11I THE "PuT ON INQUIRY" TEST • . • . • • • . • . • . • . 463 D. CONCLUSIONSFROM PART II . 467 III. KNOWING AsSISTANCE .. ·I·............................ 467 A. THEAIR CANADA DECISION . • • • . • . 468 IV. -

Cambridge University Press 978-1-316-62194-3 — Equity and Trusts in Australia Michael Bryan , Vicki Vann , Susan Barkehall Thomas Index More Information INDEX

Cambridge University Press 978-1-316-62194-3 — Equity and Trusts in Australia Michael Bryan , Vicki Vann , Susan Barkehall Thomas Index More Information INDEX accounts of profits, 54–5, 169 limitation statutes, 84–5 remedies for. See remedies allowances, 57–8 unclean hands, 86–8, 168 for breach of trust breach of confidence, 197 beneficiaries, 206 ‘but for’ test, 65–6, 333 calculation of, 55–7 administration of trust and, acquiescence, 85–6 207 calculation of equitable as equitable defence to creditors’ rights and, 313–14 compensation, 60–1 breach of trust, 329–30 differences between fixed breach of fiduciary duty, overlap with laches, 85–6 and discretionary trusts 63–5 advancement for, 207 breach of trust, 61–3 presumption of, 357–9 ‘gift-over’ right, 208–9 calculation of equitable agency indemnification of trustees, damages trusts and, 210–11 311–13 causation standard, 65–6 aggravated damages, 68 interest, trustees’ right to common law adjustments to Anton Piller order, 39 impound, 314 quantum, 66–8 Aristotle, 4 investment of trust funds, categories of constructive trusts, assessment of equitable 297, 299 371 damages, 51 ‘list certainty’, 227 as remedy to proprietary in addition to injunction or sui juris, 278, 312 estoppel, 380–2 specific performance, 51 trust property and, 208 as restitutionary remedy in substitution for injunction trustees’ right to recover for unjust enrichment, or specific performance, overpayment from, 315 380–2 51–2 breach of confidence, 17–18, 47, Baumgartner constructive assignments 50, 68 trusts, 375–9 equitable property, 138–9 defences to. See defences to common intention, family future property, 137–8 breach of confidence property disputes and, gifts, 133–6 remedies for. -

CLAIMS AGAINST THIRD PARTIES Jeremy Bamford & Simon Passfield, Guildhall Chambers

CLAIMS AGAINST THIRD PARTIES Jeremy Bamford & Simon Passfield, Guildhall Chambers A. Introduction 1. This paper supports and provides the references for the Wonderland Ltd case study1 which will be considered during the seminar. 2. The aim of the case study is to explore claims which go beyond the usual fare of the office- holder’s statutory remedies by way of transactions at an undervalue, preference, s. 212 misfeasance claims, wrongful or fraudulent trading or transactions defrauding creditors. Instead we explore claims against third parties, where there has been a breach of the Companies Act and/or breach of fiduciary duty by directors, unlawful dividends being used as an example. B. Dividends 3. There are usually 3 potential grounds for challenging dividend payments: 3.1. the conventional technical claim made under the Companies legislation that dividends have not been paid out of profits available for that purpose and that the dividends have been paid in breach of the Companies legislation; 3.2. that the internal regulations of the company were breached and/or 3.3. breach of the common law maintenance of capital rule. We consider these in turn. B1 Part VIII CA 1985 4. In the case study the dividends were paid between 1 Sep 2007 and 1 March 2008. The relevant law is therefore Part VIII Companies Act 1985 (ss. 263 – 281 CA 1985)2. 5. A distribution of a company’s assets (which includes a dividend) can only be made out of profits available for the purpose (s. 263(1) CA 1985)3 being its accumulated, realised profits, so far as not previously utilised by distribution or capitalisation, less its accumulated, realised losses, so far as not previously written off in a reduction or reorganisation of capital duly made (s. -

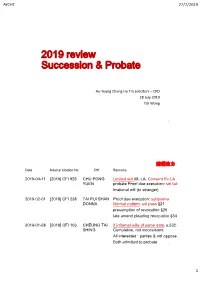

2019 Review Succession & Probate

AYCHT 27/7/2019 2019 review Succession & Probate Au‐Yeung Cheng Ho Tin solicitors –CPD 28 July 2019 Tak Wong 1 遺囑效力 Date Neutral Citation No Pltf Remarks 2019-04-11 [2019] CFI 925 CHU PONG Limited will 08, LA. Consent Rv LA YUEN probate Proof due execution: sol fail Irrational will (to stranger) 2019-02-01 [2019] CFI 238 TAI PUI SHAN Proof due execution: subpoena. DONNA Normal pattern. sol pass §21 presumption of revocation §26 late amend pleading revocation §34 2019-01-28 [2019] CFI 103 CHEUNG TAI 2 informal wills of same date. s.5(2) SHING Cumulative, not inconsistent. All interested : parties & not oppose. Both admitted to probate. 2 1 AYCHT 27/7/2019 遺囑效力 Date Neutral Citation No Pltf Remarks 2018-12-19 [2018] CFA 61 CHOY PO B v G evidence 3 limbs T/C.gap§11 CHUN fact-specific. No proper basis will instruction §18. will invalid 2019-04-18 [2019] CA 452 MOK HING Same B v G 3 limbs T/C. CHUNG fact-specific Yes proper basis. Choy Po Chun distinguished. Will instruction direct / rational Sol > sol firm. Will valid. 3 親屬關係 Date Neutral Citation No Pltf Remarks 2018-08-08 [2018] CA 491 LI CHEONG Natural dau, 1. DNA 2. copy B/C, rolled-up hearing directions 2018-10-18 [2018] CA 719 LI CHEONG Probate action in rem nature, O.15 r.13A, intended intervener, dismiss 2014-07-03 MOK HING CCL:spinster 1.no adopt §89 2.yes CHUNG i-tze 3.yes IEO s2(2)(c) 4.DWAE案 2018-10-19 [2018] CA 713 MOK HING CCL adoption v i-tze, apply to file CHUNG obituary notice, Ladd, dismiss 2019-04-18 [2019] CA 452 MOK HING CCL no formalities (adoption/i-tze) CHUNG §52, all 7 appeal grounds no merit. -

C00 Br Eq&Tr Prelims.Ps

衡平法和信托法简明案例s Briefcase on Equity and Trust Third Edition Gary Watt , MA ( Oxon), Solicitor 武 汉 大 学 出 版 社 本 书 导 读 信托制度起源于中世纪英国的 衡平 法 , 因为 当时英 国普 通法院 不承 认 受益人依赖于受托人获得的权利 , 而衡 平法 院则 总是通 过对 受托人 施加 衡 平法上的义务来支持这种权利的。 它是 英美 法系一 个独 特的制 度 , 在大 陆 法系中几乎找不到一个与之相对应的制度。又由于信托制度是建立在双重 所有权观念基础之上的 , 即受托 人享有 普通 法上 的所有 权而 受益人 享有 衡 平法上的所有权 , 所以坚持一物 一权主 义的 大陆 法国家 在接 受和移 植该 制 度的时候难免与英美法中该制度有所差异。对于学习信托法的人来说有必 要参考一下英美法学者有关信 托法的 论著。 本书就 是这 样一 本案例 教材 , 作者在理论和实务的基础上运用各 种案 例讲 述了信 托法 的基本 制度 , 这 对 于我们这些长期接受大陆法系理论教育的人来说的确是一种很新颖的教学 方式。 本书既介绍了衡平法与信托法 的历 史沿 革 , 也介绍 了它 们最近 的一 些 最新发展。全书分为六个部分 , 第一部分主要是介绍衡平法和信托法 ; 第二 部分则叙述了明示信托的设立 , 该部分又分了 8 节 , 逐一介绍了设立明示信 托行为能力与要式的要求 , 确定 性的 要求 , 赠 与的完 成与 信托的 设立 , 永 久 权与信托设立时的公共政策限制 , 目 的信托 , 公益信 托和 特殊种 类信 托 ; 第 三部分探讨了明示信托变更 的各 种方 式以及 1958 年信 托变 更法中 对于 变 更的要求 ; 第四部分则分析了受托人的地位和职责 , 同时也分析了类似于受 托人的人的地位和义务 , 该部分 又分 6 节 , 逐 一介绍 了受 托人 的职的 任命 , 受托人的职的履行 , 受托人的义 务 , 受托 人投 资的权 利及 义务 , 抚养 与预 付 以及信托违约的抗辩与免除 ; 第 五部分 则把 重点 放在拟 制信 托与回 归信 托 之上 , 讲解了推定的回归信托 , 自动的回归信托 , 地产的拟制信托 , 拟制信托 受托人的义务 , 陌生人作为拟制信托的受托人等许多内容 ; 最后作者谈到了 追及与衡平法上的救济 , 在讲到追及的时候既谈到了普通法上的追及 , 又谈 到了衡平法上的追击 , 在讲衡平 法上的 救济 的时 候则讲 到了 衡平法 上对 于 实际履行的救济和衡平法上的禁令。 本书作 为介 绍 英国 信托 法律 制度 的 基本 读物 , 内容 简明 扼要 , 通俗 易 懂。作者理论联系实际 , 借助丰富翔实的案例 , 深入浅出地勾勒出了英国信 托法的基本框架制度。这对于我们 开展 比较 研究 , 理解 和掌 握英国 美法 系 1 相关法律知识 , 借鉴和学习英美法系相对成熟的法律制度是大有裨益的。 本书中文目录、法规一览表、术语及索引部分由武汉大学民商法博士研 究生王茂祺翻译并整理 , 纰漏之处在所难免 , 希望广大读者多提宝贵意见。 译 者 2004 年 4 月 2 Glos sar y 术 语 Abbot t Fund, Re: Two old ladies 两个老年妇女 � Abergavenny’s ( Marquess of) , Re : Advancement used up 预付已用完 Abrahams, Re: 25 year old infant ? 25 岁的婴儿 ? Abrahams v Trustee in Bankruptcy -

(A) Panag. Prelims

RESTITUTION IN PRIVATE INTERNATIONAL LAW Restitution in Private International Law GEORGE PANAGOPOULOS B. A., LL.B (hons.) (Mon.) B.C.L., D.Phil. (Oxon) Barrister and Solicitor of Victoria, Australia Solicitor, England and Wales OXFORD – PORTLAND OREGON 2000 Hart Publishing Oxford and Portland, Oregon Published in North America (US and Canada) by Hart Publishing c/o International Specialized Book Services 5804 NE Hassalo Street Portland, Oregon 97213-3644 USA Distributed in the Netherlands, Belgium and Luxembourg by Intersentia, Churchillaan 108 B2900 Schoten Antwerpen Belgium © George Panagopoulos 2000 The author has asserted his right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, to be identified as the authors of this work Hart Publishing Ltd is a specialist legal publisher based in Oxford, England. To order further copies of this book or to request a list of other publications please write to: Hart Publishing Ltd, Salter’s Boatyard, Oxford OX1 4LB Telephone: +44 (0)1865 245533 or Fax: +44 (0)1865 794882 e-mail: [email protected] www.hartpub.co.uk British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Data Available ISBN 1 84113–142–3 (cloth) Typeset by Hope Services (Abingdon) Ltd. Printed in Great Britain on acid-free paper by Biddles Ltd, Guildford and King’s Lynn. “λλ πειρ ται τ ζημ α σζειν, φαιρν τ κρδο . στε τ πανορθωτικν δκαιον "ν ε#η τ μσον ζημα κα$ κρδου” &Αριστοτλη, &Ηθικ Νικομχεια, V 4 1132α 9–10, 18–19 “but (the judge) tries to equalize things by the penalty he imposes, taking away the gain . therefore the restitutionary justice is the mean between loss and gain” Aristotle, Nicomachean Ethics V 4 1132a 9–10, 18–19 Preface This book is based on my doctoral thesis, which was submitted at the University of Oxford in July 1999. -

Unconscionability As an Underlying Concept in Equity

THE DENNING LAW JOURNAL UNCONSCIONABILITY AS A UNIFYING CONCEPT IN EQUITY Mark Pawlowski* ABSTRACT This article seeks to examine the extent to which a unified concept of unconscionability can be used to rationalise related doctrines of equity, in particular, in the areas of (1) unconscionable bargains, undue influence and duress (2) proprietary estoppel (3) knowing receipt liability and (4) relief against forfeitures. The conclusion is that such a process of amalgamation may provide a principled doctrinal basis for equity’s intervention which has already found favour in the English courts. INTRODUCTION A recent discernible trend in equity has been the willingness of the English courts to adopt a broader-based doctrine of unconscionability as underlying proprietary estoppel claims and the personal liability of a stranger to a trust who has knowingly received trust property in breach of trust. The decisions in Gillett v Holt,1 Jennings v Rice2 and Campbell v Griffin3 in the context of proprietary estoppel and Bank of Credit and Commerce International (Overseas) Ltd v Akindele4 on the subject of receipt liability, demonstrate the judiciary’s growing recognition that the concept of unconscionability provides a useful mechanism for affording equitable relief against the strict insistence on legal rights or unfair and oppressive conduct. This, in turn, prompts the question whether there are other areas which would benefit from a rationalisation of principles under the one umbrella of unconscionability. The process of amalgamation, it is submitted, would be particularly useful in areas where there are currently several related (but distinct) doctrines operating together so as to give rise to confusion and overlap in the same field of law. -

Unit 5 – Equity and Trusts Suggested Answers - January 2013

LEVEL 6 - UNIT 5 – EQUITY AND TRUSTS SUGGESTED ANSWERS - JANUARY 2013 Note to Candidates and Tutors: The purpose of the suggested answers is to provide students and tutors with guidance as to the key points students should have included in their answers to the January 2013 examinations. The suggested answers set out a response that a good (merit/distinction) candidate would have provided. The suggested answers do not for all questions set out all the points which students may have included in their responses to the questions. Students will have received credit, where applicable, for other points not addressed by the suggested answers. Students and tutors should review the suggested answers in conjunction with the question papers and the Chief Examiners’ reports which provide feedback on student performance in the examination. SECTION A Question 1 This essay will examine the general characteristics of equitable remedies before examining each remedy in turn to analyse whether they are in fact strict and of limited flexibility as the question suggests. The best way to examine the general characteristics of equitable remedies is to draw comparisons with the common law. Equitable remedies are, of course discretionary, whereas the common law remedy of damages is available as of right. This does not mean that the court has absolute discretion, there are clear principles which govern the grant of equitable remedies. Equitable remedies are granted where the common law remedies would be inadequate or where the common law remedies are not available because the right is exclusively equitable. One of the key characteristics of equitable remedies is of course that they act in personam. -

KNOWING RECEIPT of FRAUDULENT FUNDS & KNOWING ASSISTANCE in BREACH of TRUST in ESTATES & TRUSTS by Justin W

KNOWING RECEIPT OF FRAUDULENT FUNDS & KNOWING ASSISTANCE IN BREACH OF TRUST IN ESTATES & TRUSTS by Justin W. de Vries1 INTRODUCTION In equity, a third party who receives money from a fiduciary, in breach of the fiduciary’s trust obligations to a beneficiary, is liable in a personal action brought by the beneficiary.2 The beneficiary does not need to show that the third party recipient committed fraud or was dishonest in acquiring the funds. The beneficiary must simply show that the third party recipient knew, or should have known, that the trustees were acting in breach of the terms of the trust when they made the transfer.3 In other words, the beneficiary must show that the third party knowingly participated in the fraud. The equitable basis for this action is the principle of unjust enrichment: there is no reason that the third party recipient should be enriched by the misappropriated property at the expense of the beneficiary. Where this occurs, the third party recipient may be compelled to return the misappropriated funds.4 The ability to pursue a third party via the claim of unjust enrichment is a useful tool for wronged beneficiaries. It is especially important where the fraudulent trustee has disappeared or died and restitution cannot be obtained from him. There are, of course, defences to the claim of unjust enrichment. Where the third party recipient does not receive notice of the trust, nor could he have otherwise known about the trust, then the 1 Justin de Vries can be reached at 416-640-2757 (Toronto) or 905-844-0900 (Oakville) or by email at [email protected]. -

STRANGER LIABILITY: a QUESTION of CONSCIENCE PROPERTY OR STANDARDS? by Kerrell Ma* PART ONE Introduction Trustees Have Some Onerous Duties

STRANGER LIABILITY: A QUESTION OF CONSCIENCE PROPERTY OR STANDARDS? by Kerrell Ma* PART ONE Introduction Trustees have some onerous duties. Their principle duty is to discharge themselves by accounting to their beneficiaries for the trust property. That duty or a duty akin to it should not be imposed lightly on any persons other than an express trustee, unless those persons' actions in relation to the trust property are such that they ought to attract such a duty. Furthermore, before equity imposes a liability on persons other than an express trustee (referred to as strangers to the trust) for participating in a breach of trust or breach of fiduciary duty there should be a clear reason for so doing. Is it because of: 1.the unconscionable behaviour of the stranger in relation to the property; or 2. the stranger's fault in not realising that the dealing with the property constitutes a breach of trust or fiduciary duty or that any assistance rendered enables a breach to be committed; or 3. the stranger's notice in respect of the breach; or 4. the stranger's unjust enrichment by receipt of property, or for more than one of these reasons? Judges and academics cannot agree on the underlying basis for the obligations imposed on strangers for receipt of property received in breach of trust or in breach of fiduciary duties or for the rendering of assistance in such breaches.1 It is then no small wonder that with the offering of different paths, the law in relation to constructive trust liability for strangers to trusts is in disarray. -

Administration of Trusts

Administration of Trusts Administration of Trusts Denis Barlin Barrister 13 Wentworth Selborne Chambers 174-180 Phillip Street SYDNEY NSW 2000 (02) 9231 6646 [email protected] page 1 Administration of Trusts Contents 1 General principles – trusts ................................................................................. 4 1.1 Trustee’ Duties .................................................................................................................. 4 1.2 Duty to carry out terms of the trust .................................................................................. 5 1.3 Duty of care in the management of the trust affairs ........................................................ 5 1.4 Duty to act impartially ....................................................................................................... 7 1.5 Duty to perform trusts honestly and in good faith for the benefit of beneficiaries ......... 7 1.6 Bankruptcy Act considerations.......................................................................................... 8 1.7 Undervalue transfers ......................................................................................................... 8 1.8 Transfers to defeat creditors ........................................................................................... 10 2 The Court’s power to remove a trustee ............................................................ 12 3 Statutory power of appointment ..................................................................... 16 4 The