An Ethnography of Mixed Martial Arts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Graderingsbestammelser Jujutsu Vuxn a Ronin Do Fight Gym 2018 07 15

1 Ronin Do Fight Gym Graderingsbestämmelser vuxna JU JUTSU 2018-07-15 Ronin Do Fight Gym Graderingsbestämmelser vuxna 2018-07-15 Ju Jutsu 2 Ronin Do Fight Gym Graderingsbestämmelser vuxna JU JUTSU 2018-07-15 Yellow Belt 5 Kyu Ju jutsu 10 push ups 10 sit ups 55 cm front split and side split Tai Sabaki (Body shifting / Body control) Tai Sabaki 1 – 8 Ukemi Waza (falling techniques) Mae Ukemi Ushiro Ukemi Nage Waza (throwing techniques) Ikkyo /Ude Gatame Nikkyo/ Kote Mawashi O soto Gari Kesa Gatame Jigo Waza (escape techniques) Uke ends up on the floor after each technique. Double wristlock frontal attack. Single wristlock frontal attack. Double wristlock attack from behind. 3 Ronin Do Fight Gym Graderingsbestämmelser vuxna JU JUTSU 2018-07-15 Orange Belt 4 Kyu Ju jutsu 15 push ups 15 sit ups 50 cm front split and side split Tai Sabaki (body shifting) Tai Sabaki 1 – 16 Dashi Waza (standing positions) Shiko Dashi Neko Ashi Dashi Ukemi Waza (falling techniques) Mae Ukemi above 2 people standing on their hands and knees. Daisharin. Nage Waza (throwing techniques) Aiki Otoshi Sankyo/ Kote Hineri Kibusa Gaeshi Kata Gatame 4 Ronin Do Fight Gym Graderingsbestämmelser vuxna JU JUTSU 2018-07-15 Jigo Waza (escape techniques) Uke ends up on the floor after each technique. Double wristlock frontal attack 2 different sets. Single wristlock frontal attack 2 different sets. Double wristlock attack from behind 2 different sets. Defense against 1 Geri. Defense against 1 Tzuki. Randori (sparring with grips, punches and kicks) 1 time x 2 minutes Ne Waza (ground wrestling). -

Journal of Combat Sports Medicine

Association of Ringside Physicians Journal of Combat Sports Medicine Volume 2, Issue 2 July 2020 Journal of Combat Sports Medicine | Editor-in-Chief, Editorial Board Nitin K. Sethi, MD, MBBS, FAAN, is a board certified neurologist with interests in Clinical Neurology, Epilepsy and Sleep Medicine. After completing his medical school from Maulana Azad Medical College (MAMC), University of Delhi, he did his residency in Internal Medicine (Diplomate of National Board, Internal Medicine) in India. He completed his neurology residency from Saint Vincent’s Medical Center, New York and fellowship in epilepsy and clinical neurophysiology from Weill Cornell Medical Center, New York. Dr. Sethi is a Diplomate of the American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology (ABPN), Diplomate of American Board of Clinical Neurophysiology (ABCN) with added competency in Central Clinical Neurophysiology, Epilepsy Monitor- ing and Intraoperative Monitoring, Diplomate of American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology (ABPN) with added competency in Epilepsy, Diplomate of American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology (ABPN) with added competency in Sleep Medicine and also a Diplomate American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM)/Association of Ringside Physicians (ARP) and a Certified Ringside Physician. He is a fellow of the American Academy of Neurology (FAAN) and serves on the Board of the Associa- tion of Ringside Physicians. He currently serves as Associate Professor of Neurology, New York-Presbyterian Hospital, Weill Cornell Medical Center and Chief Medical Officer of the New York State Athletic Commission. | Journal of Combat Sports Medicine Editorial Staff Susan Rees, Senior Managing Editor Email: [email protected] Susan Rees, The Rees Group President and CEO, has over 30 years of association experience. -

Celebrating Cimarron a History in by Beverly Ponterio Staff Writer by Garett Franklyn Progress Staff Writer

I N BACKCOUNTRY CAMP FEATURES BACKCOUNTRY COOKING RECIPES STAFF HIGHLIGHT PEACHES S PAGES 7-9 PAGE 10 PAGE 23 I D E PhilmontScoutRanch.org June 29, 2012 Issue 4 PhilNewsCelebrating Cimarron A History in By Beverly Ponterio Staff Writer By Garett Franklyn Progress Staff Writer Visitors peruse the historic artifacts on the walls of the St. James Hotel on Saturday, June 23, 2012. ERIN NASH/PHILNEWS PHOTOGRAPHER A tarnished bronze register what it’s changed into.” sits at the front desk of the St. It’s a history that began in David VanDeValdy, a traditional woodsmith, handcrafts household items such as kitchen utensils and James Hotel, a $5.01 still tallied 1872 when the hotel was built by benches. He traveled from Texas to share his trade. LYNN DECAPO/PHILNEWS PHOTOGRAPHER on the display from the last Henri Lambert, who was once The sky was an incredible with bone handles. Everything hand using traditional old tools. fingers that punched them in. the personal chef to President blue as the sun beat down on the seemed homemade and some At his tent, VanDeValdy Nearby is the more modern and Lincoln. Since then, it’s been vendors’ tents Saturday morning were made right in front of you was set up and making cooking functioning one worked by the the host not only of guests, but at Cimarron Days. There was as you walked around. utensils, a labor of love for him. receptionist. gunfights, gambling and maybe music playing over loudspeakers One Texan vendor, David He said, while utensils are the The contrast between old even ghosts. -

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE July 4, 2020 [email protected] PANCRASE 316, July 24, 2020 – Studio Coast, Tokyo Bout Hype A

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE July 4, 2020 PANCRASE 316, July 24, 2020 – Studio Coast, Tokyo Bout Hype After a five-month hiatus, the legendary promotion Pancrase sets off the summer fireworks with a stellar mixed martial card. Studio Coast plays host to 8 main card bouts, 3 preliminary match ups, and 12 bouts in the continuation of the 2020 Neo Blood Tournament heats on July 24th in the first event since February. Reigning Featherweight King of Pancrase Champion, Isao Kobayashi headlines the main event in a non-title bout against Akira Okada who drops down from Featherweight to meet him. The Never Quit gym ace and Bellator veteran, Kobayashi is a former Pancrase Lightweight Champion. The ripped and powerful Okada has a tough welcome to the Featherweight division, but possesses notoriously frightening physical power. “Isao” the reigning Featherweight King of Pancrase Champion, has been unstoppable in nearly three years. He claimed the interim title by way of disqualification due to a grounded knee at Pancrase 295, and following orbital surgery and recovery, he went on to capture the undisputed King of Pancrase belt from Nazareno Malagarie at Pancrase 305 in May 2019. Known to fans simply as “Akira”, he is widely feared as one of the hardest hitting Pancrase Lightweights, and steps away from his 5th ranked spot in the bracket to face Kobayashi. The 33-year-old has faced some of the best from around the world, and will thrive under the pressure of this bout. A change in weight class could be the test he needs right now. The co-main event sees Emiko Raika collide with Takayo Hashi in what promises to be a test of skills and experience, mixed with sheer will-to-win guts and determination. -

BJJY Technique Cross-Index Chart

BUDOSHIN JU-JITSU KATA (Professor Kirby's JB=Budoshin Jujitsu Basic Book , JI=Budoshin Jujitsu Intermediate Book, JN=Budoshin Jujitsu Nerve Techniques, V= Budoshin Jujitsu DVD Series) Attack Defense Falls & Rolls Basic Side Fall (Yoko Ukemi) JB-36/V1 Falls & Rolls Basic Back Roll/Fall (Ushiro Ukemi) JB-38/V1 Falls & Rolls Basic Forward Roll (Mae Ukemi) JB-40/V1 Falls & Rolls Basic Forward Fall (Mae Ukemi) JB-42/V1 1 Round Strike Outer Rear Sweeping Throw (Osoto Gari)-Knee Drop Body Strike (Karada Tatake) JB-70/V2-4 2 Cross Wrist Grab Wristlock Takedown (Tekubi Shimi Waza) JI-166/JI-164 3 Double Lapel Grab Double Strike Turning Throw (Ude No Tatake) With Elbow Roll Submission (Hiji Tatake Shimi Waza) JI-84 4 Aggressive Handshake Thumb Tip Press Side Throw (Ube Shioku Waza Yoko Nage) JN-180/V1-12 5 2 Hand Front Choke Throat (Trachea) Attack (Nodo Shioku Waza) JB-54/V1-6 6 Front Bear Hug (Under Arms) Nerve Wheel Throw (Karada Shioku Waza) JB-92/V2-11 7 Rear Bear Hug (Over/Under) Leg Lift (Ashi Ushiro Nage) With Groin Stomp Submission (Kinteki Tatake) JB-50/V1-8 8 Side Sleeve Grab Elbow Lift (Hiji Waza) JB-114/V4-12 9 Straight Knife Lunge Basic Hand Throw (Te Nage) With Wrist or Elbow-Snap Submission (Te/Hiji Maki) JB-58/V1-5, JI-128 Participate in The Weekly Pad Drills/Fundamental Karate & Ju-Jitsu Self-Defense Techniques (10 Week Rotation) 1 Round Strike Basic Drop Throw (Tai-Otoshi) With Wrist-Press Knee-Drop Submission (Tekubi Shimi Waza/Shioku Waza) JB-48/V1-3 2 Double Front Wrist Grab Wrist Side Throw (Haiai Nage or Tekubi Yoko Nage) -

Youth Participation and Injury Risk in Martial Arts Rebecca A

CLINICAL REPORT Guidance for the Clinician in Rendering Pediatric Care Youth Participation and Injury Risk in Martial Arts Rebecca A. Demorest, MD, FAAP, Chris Koutures, MD, FAAP, COUNCIL ON SPORTS MEDICINE AND FITNESS The martial arts can provide children and adolescents with vigorous levels abstract of physical exercise that can improve overall physical fi tness. The various types of martial arts encompass noncontact basic forms and techniques that may have a lower relative risk of injury. Contact-based sparring with competitive training and bouts have a higher risk of injury. This clinical report describes important techniques and movement patterns in several types of martial arts and reviews frequently reported injuries encountered in each discipline, with focused discussions of higher risk activities. Some This document is copyrighted and is property of the American Academy of Pediatrics and its Board of Directors. All authors have of these higher risk activities include blows to the head and choking or fi led confl ict of interest statements with the American Academy of Pediatrics. Any confl icts have been resolved through a process submission movements that may cause concussions or signifi cant head approved by the Board of Directors. The American Academy of injuries. The roles of rule changes, documented benefi ts of protective Pediatrics has neither solicited nor accepted any commercial involvement in the development of the content of this publication. equipment, and changes in training recommendations in attempts to reduce Clinical reports from the American Academy of Pediatrics benefi t from injury are critically assessed. This information is intended to help pediatric expertise and resources of liaisons and internal (AAP) and external health care providers counsel patients and families in encouraging safe reviewers. -

Martial Arts from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia for Other Uses, See Martial Arts (Disambiguation)

Martial arts From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia For other uses, see Martial arts (disambiguation). This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (November 2011) Martial arts are extensive systems of codified practices and traditions of combat, practiced for a variety of reasons, including self-defense, competition, physical health and fitness, as well as mental and spiritual development. The term martial art has become heavily associated with the fighting arts of eastern Asia, but was originally used in regard to the combat systems of Europe as early as the 1550s. An English fencing manual of 1639 used the term in reference specifically to the "Science and Art" of swordplay. The term is ultimately derived from Latin, martial arts being the "Arts of Mars," the Roman god of war.[1] Some martial arts are considered 'traditional' and tied to an ethnic, cultural or religious background, while others are modern systems developed either by a founder or an association. Contents [hide] • 1 Variation and scope ○ 1.1 By technical focus ○ 1.2 By application or intent • 2 History ○ 2.1 Historical martial arts ○ 2.2 Folk styles ○ 2.3 Modern history • 3 Testing and competition ○ 3.1 Light- and medium-contact ○ 3.2 Full-contact ○ 3.3 Martial Sport • 4 Health and fitness benefits • 5 Self-defense, military and law enforcement applications • 6 Martial arts industry • 7 See also ○ 7.1 Equipment • 8 References • 9 External links [edit] Variation and scope Martial arts may be categorized along a variety of criteria, including: • Traditional or historical arts and contemporary styles of folk wrestling vs. -

2016 /2017 NFHS Wrestling Rules

2016 /2017 NFHS wrestling Rules The OHSAA and the OWOA wish to thank the National Federation of State High School Associations for the permission to use the photographs to illustrate and better visually explain situations shown in the back of the 2016/17 rule book. © Copyright 2016 by OHSAA and OWOA Falls And Nearfalls—Inbounds—Starting Positions— Technical Violations—Illegal Holds—Potentially Dangerous (5-11-2) A fall or nearfall is scored when (5-11-2) A near fall may be scored when the any part of both scapula are inbounds and the defensive wrestler is held in a high bridge shoulders are over or outside the boundary or on both elbows. line. Hand over nose and mouth that restricts breathing (5-11-2) A near fall may be scored when the (5-14-2) When the defensive wrestler in a wrestler is held in a high bridge or on both pinning situation, illegally puts pressure over elbows the opponents’s mouth, nose, or neck, it shall be penalized. Hand over nose and mouth Out-of-bounds that restricts Inbounds breathing Out-of-bounds Out-of-bounds Inbounds (5-15-1) Contestants are considered to be (5-14-2) Any hold/maneuver over the inbounds if the supporting points of either opponent’s mouth, nose throat or neck which wrestler are inside or on but not beyond the restricts breathing or circulation is illegal boundary 2 Starting Position Legal Neutral Starting Position (5-19-4) Both wrestlers must have one foot on the Legal green or red area of the starting lines and the other foot on line extended, or behind the foot on the line. -

Kouketsu Takuma ENTREVISTA EXCLUSIVA

REVISTA BIMESTRAL DE ARTES MARCIALES Nº23 año IV KYOKUSHIN Kouketsu TAKUMA ENTREVISTA EXCLUSIVA El Taoísmo y la Espada Las acrobacias en el mundo del cine El principio de no violencia en Aikido El boxeo interno de la familia Wang Kenpo-Kai: Un Kenpo tradicional japonés Las esgrimas de palos de Canarias. 2ª pte. Entrevista al maestro Suekichi Naito Sumario 4 Noticias 6 40 Aniversario del Belsa Dojo. XXII HARU GASSUKU [email protected] [Por Pedro Hidalgo] www.elbudoka.es Kyokushin. Entrevista a Kouketsu Takuma 8 Dirección, redacción, [Por Pedro Hidalgo] administración y publicidad: 18 El Taoísmo y la Espada [Por “Zi Xiao” Alex Mieza] El principio de no violencia en Aikido 22 Editorial “Alas” [Por José Santos Nalda Albiac] C/ Villarroel, 124 08011 Barcelona Claves de liderazgo deportivo “de entrenador a entrenador” 28 Telf y Fax: 93 453 75 06 [Por Jonathan Mendoza] [email protected] www.editorial-alas.com 34 El concepto de la transformación suave en el boxeo interno de la familia Wang [Por Francisco J. Soriano] La dirección no se responsabiliza de las opiniones 40 Tras los orígenes de las esgrimas de palos de Canarias. Segunda parte de sus colaboradores, ni siquiera las comparte. La publicidad insertada en “El Budoka 2.0” es responsa- [Por Alfonso Acosta Gil] bilidad única y exclusiva de los anunciantes. No se devuelven originales remitidos Entrevista al maestro Suekichi Naito, 10º Dan Goju-ryu Shorei-Kan 46 espontáneamente, ni se mantiene correspondencia [Por Alexis Alcón] sobre los mismos. 56 Las páginas del DNK: KENPO-KAI. Un Kenpo tradicional japonés [Por Pilar Martínez] Director: José Sala Comas Jefe de redacción: Jordi Sala F. -

Are Ufc Fighters Employees Or Independent Contractors?

Conklin Book Proof (Do Not Delete) 4/27/20 8:42 PM TWO CLASSIFICATIONS ENTER, ONE CLASSIFICATION LEAVES: ARE UFC FIGHTERS EMPLOYEES OR INDEPENDENT CONTRACTORS? MICHAEL CONKLIN* I. INTRODUCTION The fighters who compete in the Ultimate Fighting Championship (“UFC”) are currently classified as independent contractors. However, this classification appears to contradict the level of control that the UFC exerts over its fighters. This independent contractor classification severely limits the fighters’ benefits, workplace protections, and ability to unionize. Furthermore, the friendship between UFC’s brash president Dana White and President Donald Trump—who is responsible for making appointments to the National Labor Relations Board (“NLRB”)—has added a new twist to this issue.1 An attorney representing a former UFC fighter claimed this friendship resulted in a biased NLRB determination in their case.2 This article provides a detailed examination of the relationship between the UFC and its fighters, the relevance of worker classifications, and the case law involving workers in related fields. Finally, it performs an analysis of the proper classification of UFC fighters using the Internal Revenue Service (“IRS”) Twenty-Factor Test. II. UFC BACKGROUND The UFC is the world’s leading mixed martial arts (“MMA”) promotion. MMA is a one-on-one combat sport that combines elements of different martial arts such as boxing, judo, wrestling, jiu-jitsu, and karate. UFC bouts always take place in the trademarked Octagon, which is an eight-sided cage.3 The first UFC event was held in 1993 and had limited rules and limited fighter protections as compared to the modern-day events.4 UFC 15 was promoted as “deadly” and an event “where anything can happen and probably will.”6 The brutality of the early UFC events led to Senator John * Powell Endowed Professor of Business Law, Angelo State University. -

2015 Topps UFC Chronicles Checklist

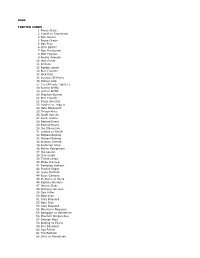

BASE FIGHTER CARDS 1 Royce Gracie 2 Gracie vs Jimmerson 3 Dan Severn 4 Royce Gracie 5 Don Frye 6 Vitor Belfort 7 Dan Henderson 8 Matt Hughes 9 Andrei Arlovski 10 Jens Pulver 11 BJ Penn 12 Robbie Lawler 13 Rich Franklin 14 Nick Diaz 15 Georges St-Pierre 16 Patrick Côté 17 The Ultimate Fighter 1 18 Forrest Griffin 19 Forrest Griffin 20 Stephan Bonnar 21 Rich Franklin 22 Diego Sanchez 23 Hughes vs Trigg II 24 Nate Marquardt 25 Thiago Alves 26 Chael Sonnen 27 Keith Jardine 28 Rashad Evans 29 Rashad Evans 30 Joe Stevenson 31 Ludwig vs Goulet 32 Michael Bisping 33 Michael Bisping 34 Arianny Celeste 35 Anderson Silva 36 Martin Kampmann 37 Joe Lauzon 38 Clay Guida 39 Thales Leites 40 Mirko Cro Cop 41 Rampage Jackson 42 Frankie Edgar 43 Lyoto Machida 44 Roan Carneiro 45 St-Pierre vs Serra 46 Fabricio Werdum 47 Dennis Siver 48 Anthony Johnson 49 Cole Miller 50 Nate Diaz 51 Gray Maynard 52 Nate Diaz 53 Gray Maynard 54 Minotauro Nogueira 55 Rampage vs Henderson 56 Maurício Shogun Rua 57 Demian Maia 58 Bisping vs Evans 59 Ben Saunders 60 Soa Palelei 61 Tim Boetsch 62 Silva vs Henderson 63 Cain Velasquez 64 Shane Carwin 65 Matt Brown 66 CB Dollaway 67 Amir Sadollah 68 CB Dollaway 69 Dan Miller 70 Fitch vs Larson 71 Jim Miller 72 Baron vs Miller 73 Junior Dos Santos 74 Rafael dos Anjos 75 Ryan Bader 76 Tom Lawlor 77 Efrain Escudero 78 Ryan Bader 79 Mark Muñoz 80 Carlos Condit 81 Brian Stann 82 TJ Grant 83 Ross Pearson 84 Ross Pearson 85 Johny Hendricks 86 Todd Duffee 87 Jake Ellenberger 88 John Howard 89 Nik Lentz 90 Ben Rothwell 91 Alexander Gustafsson -

![[ZFJ] Livre Free Mastering the Twister: Jiujitsu For](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9861/zfj-livre-free-mastering-the-twister-jiujitsu-for-709861.webp)

[ZFJ] Livre Free Mastering the Twister: Jiujitsu For

Register Free To Download Files | File Name : Mastering The Twister: Jiujitsu For Mixed Martial Arts Competition PDF MASTERING THE TWISTER: JIUJITSU FOR MIXED MARTIAL ARTS COMPETITION Tapa blanda 18 diciembre 2007 Author : Eddie Bravo Erich Krauss Glen Cordoza Descripcin del productoCrticas"Eddie Bravo's approach to jiu-jitsu is so unusual and innovated that it's literally a completely separate branch off the jiu-jitsu tree. And it's not just different; it's actually better. Much better."-'Joe Rogan, UFC commentator and host of NBC's Fear FactorNota de la solapa Biografa del autorEddie Bravo is the world-renowned jiu-jitsu practitioner who submitted the legendary Royler Gracie in the most prestigious jiu-jitsu competition in the world. Erich Krauss is a professional Muay Thai kickboxer who has trained and competed in Thailand. Glen Cordoza is a professional Mixed Martial Arts fighter.Leer ms Great sytem for modern mma Eddie Bravo is in my opinion the next Helio Gracie as far as jiu jitsu goes. Helio took japanese jiu jitsu which used more strength holds and adapted it to his smaller size by using leverage and the gi. Eddie Bravo has taken the Gracie jiu jitsu system and adapted it to mixed martial arts fighting without a gi. When no gi is present you must use other positions and techniques to accomplish similar goals. This book will teach you that system. Beware flexibility is not required to practice some techniques, but most will require a yoga type level of flexibilty. But hey if you wanna throw up crazy arm bars and triangles you must be flexible anyway.