Pharmacology/Toxicology Case Studies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Development of a Quantitative PCR Assay for the Detection And

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/544247; this version posted February 8, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. Development of a quantitative PCR assay for the detection and enumeration of a potentially ciguatoxin-producing dinoflagellate, Gambierdiscus lapillus (Gonyaulacales, Dinophyceae). Key words:Ciguatera fish poisoning, Gambierdiscus lapillus, Quantitative PCR assay, Great Barrier Reef Kretzschmar, A.L.1,2, Verma, A.1, Kohli, G.S.1,3, Murray, S.A.1 1Climate Change Cluster (C3), University of Technology Sydney, Ultimo, 2007 NSW, Australia 2ithree institute (i3), University of Technology Sydney, Ultimo, 2007 NSW, Australia, [email protected] 3Alfred Wegener-Institut Helmholtz-Zentrum fr Polar- und Meeresforschung, Am Handelshafen 12, 27570, Bremerhaven, Germany Abstract Ciguatera fish poisoning is an illness contracted through the ingestion of seafood containing ciguatoxins. It is prevalent in tropical regions worldwide, including in Australia. Ciguatoxins are produced by some species of Gambierdiscus. Therefore, screening of Gambierdiscus species identification through quantitative PCR (qPCR), along with the determination of species toxicity, can be useful in monitoring potential ciguatera risk in these regions. In Australia, the identity, distribution and abundance of ciguatoxin producing Gambierdiscus spp. is largely unknown. In this study we developed a rapid qPCR assay to quantify the presence and abundance of Gambierdiscus lapillus, a likely ciguatoxic species. We assessed the specificity and efficiency of the qPCR assay. The assay was tested on 25 environmental samples from the Heron Island reef in the southern Great Barrier Reef, a ciguatera endemic region, in triplicate to determine the presence and patchiness of these species across samples from Chnoospora sp., Padina sp. -

EPA's Guidance to Protect POTW Workers from Toxic and Reactive

United States Office Of Water EPA 812-B-92-001 Environmental Protection (EN-336) NTIS No. PB92-173-236 Agency June 1992 EPA Guidance To Protect POTW Workers From Toxic And Reactive Gases And Vapors DISCLAIMER: This is a guidance document only. Compliance with these procedures cannot guarantee worker safety in all cases. Each POTW must assess whether measures more protective of worker health are necessary at each facility. Confined-spaceentry, worker right-to-know, and worker health and safety issues not directly related to toxic or reactive discharges to POTWs are beyond the scope of this guidance document and are not addressed. Additional copies of this document and other EPA documentsreferenced in this document can be obtained by writing to the National Technical Information Service (NTIS) at: 5285 Port Royal Rd. Springfield, VA 22161 Ph #: 703-487-4650 (NTIS charges a fee for each document.) FOREWORD In 1978, EPA promulgated the General Pretreatment Regulations [40 CFR Part 403] to control industrial discharges to POTWs that damage the collection system, interfere with treatment plant operations, limit sewage sludge disposal options, or pass through inadequately treated into receiving waters On July 24, 1990, EPA amended the General Pretreatment Regulations to respond to the findings and recommendations of the Report to Congress onthe Discharge of Hazardous Wastesto Publicly Owned Treatment Works (the “Domestic Sewage Study”), which identified ways to strengthen the control of hazardous wastes discharged to POTWs. The amendments add -

Benzodiazepine & Alcohol Co-Ingestion

The Journal of COLLEGIATE EMERGENCY MEDICAL SERVICES ISSN: 2576-3687 (Print) 2576-3695 (Online) Journal Website: https://www.collegeems.com Benzodiazepine & Alcohol Co-Ingestion: Implications for Collegiate-Based Emergency Medical Services David Goroff & Alexander Farinelli Keywords: alcohol, benzodiazepines, collegiate-based emergency medical services, toxicology Citation (AMA Style): Goroff D, Farinelli A. Benzodiazepine and Alcohol Co-In- gestion. J Coll Emerg Med Serv. 2018; 1(2): 19-23. https://doi.org/10.30542/ JCEMS.2018.01.02.04 Electronic Link: https://doi.org/10.30542/JCEMS.2018.01.02.04 Published Online: August 8, 2018 Published in Print: August 13, 2018 (Volume 1: Issue 2) Copyright: © 2018 Goroff & Farinelli. This is an OPEN ACCESS article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribu- tion 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) License, which permits unrestrict- ed use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. The full license is available at: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ CLINICAL REVIEW Benzodiazepine & Alcohol Co-Ingestion: Implications for Collegiate-Based Emergency Medical Services David Goroff, MS, NRP & Alexander Farinelli, BS, NRP ABSTRACT KEYWORDS: alcohol, The co-ingestion of benzodiazepines and alcohol presents a unique challenge to colle- benzodiazepines, collegiate- giate EMS providers, due to the pharmacological interaction of the two substances and based emergency medical the variable patient presentations. Given the likelihood that collegiate EMS providers services, toxicology will be called to treat a patient who has co-ingested benzodiazepines and alcohol, this Corresponding Author and review discusses the relevant pharmacology, clinical presentation, and treatment of these Author Affiliations:Listed co-ingestion patients. -

THE ACUTE ABDOMEN Definition Abdominal Pain of Short Duration

THE ACUTE ABDOMEN Definition Abdominal pain of short duration that is usually associated with muscular rigidity, distension and vomiting, and which requires a decision whether an emergent operation is required. Problems and management options History and physical examination are central in the evaluation of the acute abdomen. However, in an ICU patient, these are often limited by sedation, paralysis and mechanical ventilation, and obscured by a protracted, complicated inhospital course. Often an acute abdomen is inferred from unexplained sepsis, hypovolaemia and abdominal distension. The need for prompt diagnosis and early treatment by no means equates with operative management. While it is a truism that correct diagnosis is the essential preliminary to correct treatment, this is probably more so in nonoperative management. On occasions, the need for operation is more obvious than the diagnosis and no delay should be incurred in an attempt to confirm the diagnosis before surgery. Frequently fluid resuscitation and antibiotics are required concurrently with the evaluation process. The approach is to evaluate the ICU patient in the context of the underlying disorder and decide on one of the following options: ∙ Immediate operation (surgery now)– the ‘bleeder’ e.g. ruptured ectopic pregnancy, ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) in the salvageable patient ∙ Emergent operation (surgery tonight)– the ‘septic’ e.g. generalized peritonitis from perforated viscus ∙ Early operation (surgery tomorrow)– the ‘obstructed’, e.g. obstructed colonic cancer ∙ Radiologically guided drainage – e.g. localized abscesses, acalculous cholecystitis, pyonephrosis ∙ Active observation and frequent reevaluation – e.g localized peritoneal signs other than in the RLQ, selected cases of endoscopic perforation . -

Guidelines for NON - CRITICAL CARE Staff Common Vasoactive Drugs These Drugs Are Used to Maintain Cardiovascular Stability

Guidelines for NON - CRITICAL CARE staff Common vasoactive drugs These drugs are used to maintain cardiovascular stability. The full guide to administration can be found on BSUH infonet > intensive care unit > clinical guidelines > inotropes These drugs MUST be given via a central venous catheter. Be given via a ‘dedicated’ line (several vasoactives can run together in one lumen of a CVC) with a 2, 3 or 4 lumen connector. given via an ICU specific syringe driver – these allow you to change the rate without pausing the infusion. All ICU pumps have ICU or HDU spray-painted on them. Be ‘double pumped’ ie: when changing syringe, the old and new infusions run concurrently to prevent loss of infusion during change UNLESS ‘RAPID CHANGE- OVER’ TECHNIQUE IS USED, DUE TO LACK OF AVAILABLE PUMPS These drugs MUST NOT be paused, stopped or disconnected suddenly – they have a short half-life and pausing/stopping/disconnection may cause rapid CVS deterioration or arrest UNLESS ‘RAPID CHANGE-OVER’ TECHNIQUE IS USED, DUE TO LACK OF AVAILABLE PUMPS be given as a bolus, or bolused via the pump – this could cause rapid CVS instability run with ANY drug other than a vasoactive drug COMMON VASOACTIVES NORADRENALINE – vasopressor: causes vasoconstriction and used to improve BP USES: sepsis, septic shock, severe hypotension not resolved with fluid ADRENALINE – inotrope: increases contractility, raises BP and HR USES: sepsis, septic shock, severe bradycardia DOBUTAMINE – intrope and vasodilator: increases contractility and reduces cardiac work USES: -

Ciguatera: Current Concepts

Ciguatera: Current concepts DAVID Z. LEVINE, DO Ciguatera poisoning develops unraveling the diagnosis may prove difficult. after ingestion of certain coral reef-asso Although the syndrome has been known for at ciated fish. With travel to and from the least hundreds of years, its mechanisms are tropics and importation of tropical food only beginning to be elucidated. Effective treat fish increasing, ciguatera has begun to ments have just begun to emerge. appear in temperate countries with more Ciguatera is a major public health prob frequency. The causative agents are cer lem in the tropics, with probably more than tain varieties of the protozoan dinofla 30,000 poisonings yearly in Puerto Rico and gellate Gambierdiscus toxicus, but bacte the US Virgin Islands alone. The endemic area ria associated with these protozoa may is bounded by latitudes 37° north and south. have a role in toxin elaboration. A specif Ciguatera in temperate countries is a concern ic "ciguatoxin" seems to cause the symptoms, because people returning from business trips, but toxicosis may also be a result of a fam vacations, or living in the tropics may have ily of toxins. Toxicosis develops from 10 been poisoned through food they had eaten. minutes to 30 hours after ingestion of poi The development of worldwide marketing of soned fish, and the syndrome can include fish from a variety of ecosystems creates a dan gastrointestinal and neurologic symptoms, ger of ciguatera intoxication in climates far as well as chills, sweating, pruritus, brady removed from sandy beaches and waving·palms. cardia, tachycardia, and long-lasting weak Outbreaks have been reported in Vermont, ness and fatigue. -

Material Safety Data Sheet Is for Carbon Dioxide Supplied in Cylinders with 33 Cubic Feet (935 Liters) Or Less Gas Capacity (DOT - 39 Cylinders)

MATERIAL SAFETY DATA SHEET Prepared to U.S. OSHA, CMA, ANSI and Canadian WHMIS Standards 1. PRODUCT AND COMPANY INFORMATION CHEMICAL NAME; CLASS: CARBON DIOXIDE SYNONYMS: Carbon Anhydride, Carbonic Acid Gas, Carbonic Anhydride, Carbon Dioxide USP CHEMICAL FAMILY NAME: Acid Anhydride FORMULA: CO2 Document Number: 50007 Note: This Material Safety Data Sheet is for Carbon Dioxide supplied in cylinders with 33 cubic feet (935 liters) or less gas capacity (DOT - 39 cylinders). For Carbon Dioxide in large cylinders refer to Document Number 10039. PRODUCT USE: Calibration of Monitoring and Research Equipment MANUFACTURED/SUPPLIED FOR: ADDRESS: 821 Chesapeake Drive Cambridge, MD 21613 EMERGENCY PHONE: CHEMTREC: 1-800-424-9300 BUSINESS PHONE: 1-410-228-6400 General MSDS Information 1-713/868-0440 Fax on Demand: 1-800/231-1366 CARBON DIOXIDE - CO2 MSDS EFFECTIVE DATE: AUGUST 31, 2005 PAGE 1 OF 9 2. HAZARD IDENTIFICATION EMERGENCY OVERVIEW: Carbon Dioxide is a colorless, odorless, non-flammable gas. Over-exposure to Carbon Dioxide can increase respiration and heart rate, possibly resulting in circulatory insufficiency, which may lead to coma and death. At concentrations between 2-10%, Carbon Dioxide can cause nausea, dizziness, headache, mental confusion, increased blood pressure and respiratory rate. Exposure to Carbon Dioxide can also cause asphyxiation, through displacement of oxygen. If the gas concentration reaches 10% or more, suffocation can occur within minutes. Moisture in the air could lead to the formation of carbonic acid which can be irritating to the eyes. SYMPTOMS OF OVER-EXPOSURE BY ROUTE OF EXPOSURE: The most significant routes of over-exposure for this gas are by inhalation, and contact with the cryogenic liquid. -

Veterinary Toxicology

GINTARAS DAUNORAS VETERINARY TOXICOLOGY Lecture notes and classes works Study kit for LUHS Veterinary Faculty Foreign Students LSMU LEIDYBOS NAMAI, KAUNAS 2012 Lietuvos sveikatos moksl ų universitetas Veterinarijos akademija Neužkre čiam ųjų lig ų katedra Gintaras Daunoras VETERINARIN Ė TOKSIKOLOGIJA Paskait ų konspektai ir praktikos darb ų aprašai Mokomoji knyga LSMU Veterinarijos fakulteto užsienio studentams LSMU LEIDYBOS NAMAI, KAUNAS 2012 UDK Dau Apsvarstyta: LSMU VA Veterinarijos fakulteto Neužkre čiam ųjų lig ų katedros pos ėdyje, 2012 m. rugs ėjo 20 d., protokolo Nr. 01 LSMU VA Veterinarijos fakulteto tarybos pos ėdyje, 2012 m. rugs ėjo 28 d., protokolo Nr. 08 Recenzavo: doc. dr. Alius Pockevi čius LSMU VA Užkre čiam ųjų lig ų katedra dr. Aidas Grigonis LSMU VA Neužkre čiam ųjų lig ų katedra CONTENTS Introduction ……………………………………………………………………………………… 7 SECTION I. Lecture notes ………………………………………………………………………. 8 1. GENERAL VETERINARY TOXICOLOGY ……….……………………………………….. 8 1.1. Veterinary toxicology aims and tasks ……………………………………………………... 8 1.2. EC and Lithuanian legal documents for hazardous substances and pollution ……………. 11 1.3. Classification of poisons ……………………………………………………………………. 12 1.4. Chemicals classification and labelling ……………………………………………………… 14 2. Toxicokinetics ………………………………………………………………………...………. 15 2.2. Migration of substances through biological membranes …………………………………… 15 2.3. ADME notion ………………………………………………………………………………. 15 2.4. Possibilities of poisons entering into an animal body and methods of absorption ……… 16 2.5. Poison distribution -

Ph.D. AC1.H3 5016 R.Pdf

UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI'I LIBRARY EVALUATING THE RISK OF CIGUATERA FISH POISONING FROM REEF FISH IN HAWAI'I: DEVELOPMENT OF ELISA APPLICATIONS FOR THE DETECTION OF CIGUATOXIN A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI'I IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN CELL AND MOLECULAR BIOLOGY MAY 2008 By Cara Empey Campora Dissertation Committee: Yoshitsugi Hokama, Chairperson Martin Rayner Andre Theriault Kenichi Yabusaki Clyde Tamaru We certify that we have read this dissertation and that, in our opinion, it is satisfactory in scope and quality as a dissertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Cell and Molecu1ar Biology. DISSERTATION COMMITTEE 1~cb:io~A ~dL tiL!Z;~ LL- L:--6/ ii Acknowledgements The author wishes to express sincere appreciation to her major professor, Dr. Yoshitsugi Hokama, for his continual support, encouragement, and guidance throughout this entire project and beyond. The author also gratefully thanks all current and former committee members, Dr. Martin Rayner, Dr. John Bertram, Dr. Andre Theriault, Dr. Kenichi Yabusaki and Dr. Clyde Tamaru, for their valuable comments, criticism and involvement through the duration of this project. I wish to acknowledge and thank the technical staff who gave their time and energy in support of this project, as well as the many individuals including Jan Dierking, Gary Dill, and Dr. Clyde Tamaru who helped obtain fish specimens to test. Without their help, this study could not have been completed. Special appreciation is extended to my husband Cory Campora and my three daughters, as well as my extended family for their patience and understanding in my pursuit of this goal. -

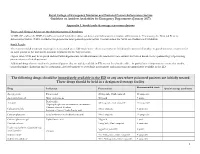

Guideline on Antidote Availability for Emergency Departments January 2017

Royal College of Emergency Medicine and National Poisons Information Service Guideline on Antidote Availability for Emergency Departments January 2017 TOXBASE and/or the BNF should be consulted for further advice on doses and indications for antidote administration and, if necessary, the National Poisons Information Service (NPIS) should be telephoned for more patient-specific advice. Contact details for NPIS are available on TOXBASE. Additional drugs that are used in the poisoned patient that are widely available in ED are not listed in the table – in particular it is important to ensure that insulin, benzodiazepines (diazepam and/or lorazepam), glyceryl trinitrate or isosorbide dinitrate and magnesium are immediately available in the ED. The following drugs should be immediately available in the ED or any area where poisoned patients are initially treated. These drugs should be held in a designated storage facility* The stock held should be sufficient to initiate treatment (stocking guidance is in Appendix 1). Drug Indication Acetylcysteine Paracetamol Activated charcoal Many oral poisons Atropine Organophosphorus or carbamate insecticides Bradycardia Calcium chloride Calcium channel blockers Systemic effects of hydrofluoric acid Calcium gluconate Local infiltration for hydrofluoric acid Calcium gluconate gel Hydrofluoric acid Cyanide antidotes Cyanide Dicobalt edetate The choice of antidote depends on the severity of poisoning, certainty of diagnosis and cause Hydroxocobalamin (Cyanokit®) of poisoning/source of cyanide. Sodium nitrite - Dicobalt edetate is the antidote of choice in severe cases when there is a high clinical Sodium thiosulphate suspicion of cyanide poisoning e.g. after cyanide salt exposure. - Hydroxocobalamin (Cyanokit®) should be considered in smoke inhalation victims who have a severe lactic acidosis, are comatose, in cardiac arrest or have significant cardiovascular compromise - Sodium nitrite may be used if dicobalt edetate is not available. -

Managing Envenomations

ResidentOfficial Publication of the Emergency Medicine Residents’ Association June/July 2021 VOL 48 / ISSUE 3 Managing Envenomations How to Sustain a Career: Peer Support Guide to ABEM Certi ication We Help Healers SCP Reach New Heights Health Meet Your Medical Career Dream Team SCP Health Step Right Up, Residents! As you’re transitioning from residency to begin your career, our team is here to create a tailored environment for you that fosters growth and delivers rewarding daily work experiences. Explore clinical careers at scp-health.com/explore TOGETHER, WE HEAL Welcome to a New Academic Year! uly marks a turning point each year, as new interns arrive in programs throughout Jthe country, newly graduated residents launch the next phase of their careers, and medical students take the next steps in their journey to residency. DO YOU KNOW HOW EMRA CAN HELP? Resources for Interns Resources for PGY2+ Resources for Students All EM programs will receive EMRA residents members receive the EMRA shows up for medical students Intern Kits this summer with nearly 10-pound EMRA Resident Kit upon interested in this specialty. From resources that offer immediate first joining EMRA. It is packed with clinical new advising content every month to backup for those first nerve-wracking resources for every rotation — some you’ll opportunities for leadership and growth, shifts. The high-yield EMRA Intern need only rarely (but prove to be clutch), and EMRA student membership is high-yield. Kit is sent for free to all EM interns some you’ll use every single shift (EMRA Plus, our online resources are unparalleled: (membership not required) and Antibiotic Guide, anyone?). -

RCEM NPIS Antidote Guideline Appx 1

Royal College of Emergency Medicine and National Poisons Information Service Guideline on Antidote Availability for Emergency Departments (January 2017) Appendix 1. Stock levels & storage recommendations Doses and Clinical Advice on the Administration of Antidotes TOXBASE and/or the BNF should be consulted for further advice on doses and indications for antidote administration. If necessary, the National Poisons Information Service (NPIS) should be telephoned for more patient-specific advice. Contact details for NPIS are available on TOXBASE. Stock Levels The recommended minimum stocking levels (rounded up to full “pack-sizes” where necessary) are based on the amount of antidote required to initiate treatment for an adult patient in the ED and to continue treatment for the first 24 hours. Higher stock levels may be required and individual departments should determine the amount of each antidote they stock based on the epidemiology of poisoning presentations to their department. Additional drugs that are used in the poisoned patient that are widely available in ED are not listed in the table – in particular it is important to ensure that insulin, benzodiazepines (diazepam and/or lorazepam), glyceryl trinitrate or isosorbide mononitrate and magnesium are immediately available in the ED. The following drugs should be immediately available in the ED or any area where poisoned patients are initially treated These drugs should be held in a designated storage facility Recommended stock Drug Indication Presentation Special storage conditions