The Evolution of the Holocene Wetland Landscape of the Humberhead Levels from a Fossil Insect Perspective

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Green-Tree Retention and Controlled Burning in Restoration and Conservation of Beetle Diversity in Boreal Forests

Dissertationes Forestales 21 Green-tree retention and controlled burning in restoration and conservation of beetle diversity in boreal forests Esko Hyvärinen Faculty of Forestry University of Joensuu Academic dissertation To be presented, with the permission of the Faculty of Forestry of the University of Joensuu, for public criticism in auditorium C2 of the University of Joensuu, Yliopistonkatu 4, Joensuu, on 9th June 2006, at 12 o’clock noon. 2 Title: Green-tree retention and controlled burning in restoration and conservation of beetle diversity in boreal forests Author: Esko Hyvärinen Dissertationes Forestales 21 Supervisors: Prof. Jari Kouki, Faculty of Forestry, University of Joensuu, Finland Docent Petri Martikainen, Faculty of Forestry, University of Joensuu, Finland Pre-examiners: Docent Jyrki Muona, Finnish Museum of Natural History, Zoological Museum, University of Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland Docent Tomas Roslin, Department of Biological and Environmental Sciences, Division of Population Biology, University of Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland Opponent: Prof. Bengt Gunnar Jonsson, Department of Natural Sciences, Mid Sweden University, Sundsvall, Sweden ISSN 1795-7389 ISBN-13: 978-951-651-130-9 (PDF) ISBN-10: 951-651-130-9 (PDF) Paper copy printed: Joensuun yliopistopaino, 2006 Publishers: The Finnish Society of Forest Science Finnish Forest Research Institute Faculty of Agriculture and Forestry of the University of Helsinki Faculty of Forestry of the University of Joensuu Editorial Office: The Finnish Society of Forest Science Unioninkatu 40A, 00170 Helsinki, Finland http://www.metla.fi/dissertationes 3 Hyvärinen, Esko 2006. Green-tree retention and controlled burning in restoration and conservation of beetle diversity in boreal forests. University of Joensuu, Faculty of Forestry. ABSTRACT The main aim of this thesis was to demonstrate the effects of green-tree retention and controlled burning on beetles (Coleoptera) in order to provide information applicable to the restoration and conservation of beetle species diversity in boreal forests. -

Water Beetles

Ireland Red List No. 1 Water beetles Ireland Red List No. 1: Water beetles G.N. Foster1, B.H. Nelson2 & Á. O Connor3 1 3 Eglinton Terrace, Ayr KA7 1JJ 2 Department of Natural Sciences, National Museums Northern Ireland 3 National Parks & Wildlife Service, Department of Environment, Heritage & Local Government Citation: Foster, G. N., Nelson, B. H. & O Connor, Á. (2009) Ireland Red List No. 1 – Water beetles. National Parks and Wildlife Service, Department of Environment, Heritage and Local Government, Dublin, Ireland. Cover images from top: Dryops similaris (© Roy Anderson); Gyrinus urinator, Hygrotus decoratus, Berosus signaticollis & Platambus maculatus (all © Jonty Denton) Ireland Red List Series Editors: N. Kingston & F. Marnell © National Parks and Wildlife Service 2009 ISSN 2009‐2016 Red list of Irish Water beetles 2009 ____________________________ CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS .................................................................................................................................... 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY...................................................................................................................................... 2 INTRODUCTION................................................................................................................................................ 3 NOMENCLATURE AND THE IRISH CHECKLIST................................................................................................ 3 COVERAGE ....................................................................................................................................................... -

Methods and Work Profile

REVIEW OF THE KNOWN AND POTENTIAL BIODIVERSITY IMPACTS OF PHYTOPHTHORA AND THE LIKELY IMPACT ON ECOSYSTEM SERVICES JANUARY 2011 Simon Conyers Kate Somerwill Carmel Ramwell John Hughes Ruth Laybourn Naomi Jones Food and Environment Research Agency Sand Hutton, York, YO41 1LZ 2 CONTENTS Executive Summary .......................................................................................................................... 8 1. Introduction ............................................................................................................ 13 1.1 Background ........................................................................................................................ 13 1.2 Objectives .......................................................................................................................... 15 2. Review of the potential impacts on species of higher trophic groups .................... 16 2.1 Introduction ........................................................................................................................ 16 2.2 Methods ............................................................................................................................. 16 2.3 Results ............................................................................................................................... 17 2.4 Discussion .......................................................................................................................... 44 3. Review of the potential impacts on ecosystem services ....................................... -

Landscape Character Assessment

OUSE WASHES Landscape Character Assessment Kite aerial photography by Bill Blake Heritage Documentation THE OUSE WASHES CONTENTS 04 Introduction Annexes 05 Context Landscape character areas mapping at 06 Study area 1:25,000 08 Structure of the report Note: this is provided as a separate document 09 ‘Fen islands’ and roddons Evolution of the landscape adjacent to the Ouse Washes 010 Physical influences 020 Human influences 033 Biodiversity 035 Landscape change 040 Guidance for managing landscape change 047 Landscape character The pattern of arable fields, 048 Overview of landscape character types shelterbelts and dykes has a and landscape character areas striking geometry 052 Landscape character areas 053 i Denver 059 ii Nordelph to 10 Mile Bank 067 iii Old Croft River 076 iv. Pymoor 082 v Manea to Langwood Fen 089 vi Fen Isles 098 vii Meadland to Lower Delphs Reeds, wet meadows and wetlands at the Welney 105 viii Ouse Valley Wetlands Wildlife Trust Reserve 116 ix Ouse Washes 03 THE OUSE WASHES INTRODUCTION Introduction Context Sets the scene Objectives Purpose of the study Study area Rationale for the Landscape Partnership area boundary A unique archaeological landscape Structure of the report Kite aerial photography by Bill Blake Heritage Documentation THE OUSE WASHES INTRODUCTION Introduction Contains Ordnance Survey data © Crown copyright and database right 2013 Context Ouse Washes LP boundary Wisbech County boundary This landscape character assessment (LCA) was District boundary A Road commissioned in 2013 by Cambridgeshire ACRE Downham as part of the suite of documents required for B Road Market a Landscape Partnership (LP) Heritage Lottery Railway Nordelph Fund bid entitled ‘Ouse Washes: The Heart of River Denver the Fens.’ However, it is intended to be a stand- Water bodies alone report which describes the distinctive March Hilgay character of this part of the Fen Basin that Lincolnshire Whittlesea contains the Ouse Washes and supports the South Holland District Welney positive management of the area. -

Hull's Flying High..!

9 Queen’s Gardens 11 City Walls & Citadel Hull Road, HU1 2AB Hull’s fortifications were established in the early 14th century, consisting of the city walls, four main gates and Hull’s flying high.. up to thirty towers. ! Demolished during The future’s bright! the 1860s, the lasting 13 Paragon Interchange segment of Hull’s Amy Johnson,Wow!! the first Civil engineers shape our world and we built this city... Ferensway, HU1 3UT female pilot to fly alone citadel - now to be seen from Britain to Australia, was improve lives. If you want to make born in Hull on Wow!! at Victoria Dock - is all 1st July 1903. a real difference, why not become a that remains of a vast triangular fort dating civil engineer? Photo courtesy of Hull Daily Mail back to 1681. This area - once known as Queen’s Dock - was the site of Which of these are examples Princes Quay Shopping Centre, Hull’s first enclosed dock - excavated between 1774 and 12 Q: of Civil Engineering? 1778. The dock was the first of its kind outside London and HU1 2PQ covers a total area of 11 acres. The original name of the Dams, reservoirs, drains and sewers; transport by road, rail, dock was ‘The Old Dock’ but it was re-named ‘Queen’s’ water and air; bridges for vehicles, trains and pedestrians; when Queen Victoria visited Hull in 1854. seaports, docks, airports, canals and aqueducts; power stations, renewable energy, pipelines and the structures that support towers and buildings. The Paragon Interchange, refurbished Queen Victoria Square 10 in 2000, links the bus station to the Hull, HU1 3RQ 150-year-old Victorian train station and Queen Victoria Square was now serves over 2.25 million people. -

(Coleoptera) Caught in Traps Baited with Pheromones for Dendroctonus Rufi Pennis (Kirby) (Curculionidae: Scolytinae) in Lithuania

EKOLOGIJA. 2010. Vol. 56. No. 1–2. P. 41–46 DOI: 10.2478/v10055-010-0006-8 © Lietuvos mokslų akademija, 2010 © Lietuvos mokslų akademijos leidykla, 2010 Beetles (Coleoptera) caught in traps baited with pheromones for Dendroctonus rufi pennis (Kirby) (Curculionidae: Scolytinae) in Lithuania Henrikas Ostrauskas1, 2*, Sticky traps baited with pheromones for Dendroctonus rufi pennis were set up in the Klaipėda port and at the Vaidotai railway station alongside temporary stored timbers and Romas Ferenca2, 3 in forests along roads in June–July 2000 (21 localities across the entire Lithuania); 111 bee- tle species and 6 genera were detected. Eight trophic groups of beetles were identifi ed, and 1 State Plant Protection Service, among them the largest number (38.7% of species detected and 28.5% of beetle speci- Sukilėlių 9a, LT-11351 Vilnius, mens) presented a decaying wood and mycetobiont beetle group. Most frequent beetles Lithuania were Dasytes plumbeus (Dasytidae), Sciodrepoides watsoni (Leiodidae) and Polygraphus poligraphus (Curculionidae). Scolytinae were represented by 5 species and 83 beetle speci- 2 Nature Research Centre, mens, No D. rufi pennis was trapped. Rhacopus sahlbergi (Eucnemidae) and Anobium niti- Akademijos 2, dum (Anobiidae) beetles were caught in two localities, and the species were ascertained as LT-08412 Vilnius, Lithuania new for the Lithuanian fauna. Th ere was detected 71 new localities with the occurence of 54 beetle species rare for Lithuania. 3 Kaunas T. Ivanauskas Zoological Museum, Key words: bark beetles, sticky traps, rare Lithuanian species, new fauna species Laisvės al. 106, LT-44253 Kaunas, Lithuania INTRODUCTION risk of introducing the species via international trade. -

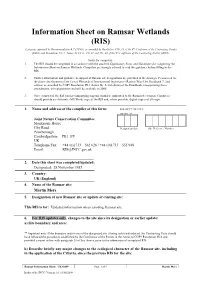

Information Sheet on Ramsar Wetlands (RIS)

Information Sheet on Ramsar Wetlands (RIS) Categories approved by Recommendation 4.7 (1990), as amended by Resolution VIII.13 of the 8th Conference of the Contracting Parties (2002) and Resolutions IX.1 Annex B, IX.6, IX.21 and IX. 22 of the 9th Conference of the Contracting Parties (2005). Notes for compilers: 1. The RIS should be completed in accordance with the attached Explanatory Notes and Guidelines for completing the Information Sheet on Ramsar Wetlands. Compilers are strongly advised to read this guidance before filling in the RIS. 2. Further information and guidance in support of Ramsar site designations are provided in the Strategic Framework for the future development of the List of Wetlands of International Importance (Ramsar Wise Use Handbook 7, 2nd edition, as amended by COP9 Resolution IX.1 Annex B). A 3rd edition of the Handbook, incorporating these amendments, is in preparation and will be available in 2006. 3. Once completed, the RIS (and accompanying map(s)) should be submitted to the Ramsar Secretariat. Compilers should provide an electronic (MS Word) copy of the RIS and, where possible, digital copies of all maps. 1. Name and address of the compiler of this form: FOR OFFICE USE ONLY. DD MM YY Joint Nature Conservation Committee Monkstone House City Road Designation date Site Reference Number Peterborough Cambridgeshire PE1 1JY UK Telephone/Fax: +44 (0)1733 – 562 626 / +44 (0)1733 – 555 948 Email: [email protected] 2. Date this sheet was completed/updated: Designated: 28 November 1985 3. Country: UK (England) 4. Name of the Ramsar site: Martin Mere 5. -

Proceedings of the Eleventh Muskeg Research Conference Macfarlane, I

NRC Publications Archive Archives des publications du CNRC Proceedings of the Eleventh Muskeg Research Conference MacFarlane, I. C.; Butler, J. For the publisher’s version, please access the DOI link below./ Pour consulter la version de l’éditeur, utilisez le lien DOI ci-dessous. Publisher’s version / Version de l'éditeur: https://doi.org/10.4224/40001140 Technical Memorandum (National Research Council of Canada. Associate Committee on Geotechnical Research), 1966-05-01 NRC Publications Archive Record / Notice des Archives des publications du CNRC : https://nrc-publications.canada.ca/eng/view/object/?id=05568728-162b-42ca-b690-d97b61f4f15c https://publications-cnrc.canada.ca/fra/voir/objet/?id=05568728-162b-42ca-b690-d97b61f4f15c Access and use of this website and the material on it are subject to the Terms and Conditions set forth at https://nrc-publications.canada.ca/eng/copyright READ THESE TERMS AND CONDITIONS CAREFULLY BEFORE USING THIS WEBSITE. L’accès à ce site Web et l’utilisation de son contenu sont assujettis aux conditions présentées dans le site https://publications-cnrc.canada.ca/fra/droits LISEZ CES CONDITIONS ATTENTIVEMENT AVANT D’UTILISER CE SITE WEB. Questions? Contact the NRC Publications Archive team at [email protected]. If you wish to email the authors directly, please see the first page of the publication for their contact information. Vous avez des questions? Nous pouvons vous aider. Pour communiquer directement avec un auteur, consultez la première page de la revue dans laquelle son article a été publié afin de trouver ses coordonnées. Si vous n’arrivez pas à les repérer, communiquez avec nous à [email protected]. -

PRS Staff 'Grey Literature' Reports for 2012

PRS staff 'grey literature' reports for 2012 presented in report number order Foster, A. (2012). Assessment of vertebrate remains from a watching brief on land to the west of Highfield, Old Trough Lane, Sandholme, Gilberdyke, East Riding of Yorkshire (site code: SGD2011). PRS 2012/01. Foster, A. (2012). Assessment of biological remains from a single sample recovered during an archaeological excavation on land to the east of Ettington Road, Wellesbourne, Stratford-upon-Avon, Warwickshire (site code: WELL11). PRS 2012/02. Carrott, J. (2012). Assessment for possible intestinal parasite remains from samples from excavations at Brignoles “La Rouge”, near Toulon, France. PRS 2012/03. Foster, A. and Carrott, J. (2012). Technical report: Biological remains from a deposit encountered during an archaeological excavation at Fountains Abbey, North Yorkshire (site code: FAO11). PRS 2012/04. Foster, A. and Carrott, J. (2012). Assessment of a single sample from an archaeological assessment at Larum House, Hempholme, East Riding of Yorkshire (site code: 008.LHH2011). PRS 2012/05. Foster, A. and Carrott, J. (2012). Assessment of biological remains from deposits encountered during archaeological recording at Hopper Hill Road, Seamer, near Scarborough, North Yorkshire (site code: HHH11). PRS 2012/06. Carrott, J., Foster, A. and Martin, G. (2012). Evaluation of biological remains from deposits encountered during excavations at the site of a proposed wind farm on land between Cowden Lane and Aldbrough Road, Withernwick, East Riding of Yorkshire (site code: WWK2011). PRS 2012/07. Foster, A., Walker, A. and Carrott, J. (2012). Assessment of biological remains from two sediment samples recovered during archaeological investigations at Easington Wetlands, East Riding of Yorkshire (site code: EWL11). -

Crossness Sewage Treatment Works Nature Reserve & Southern Marsh Aquatic Invertebrate Survey

Commissioned by Thames Water Utilities Limited Clearwater Court Vastern Road Reading RG1 8DB CROSSNESS SEWAGE TREATMENT WORKS NATURE RESERVE & SOUTHERN MARSH AQUATIC INVERTEBRATE SURVEY Report number: CPA18054 JULY 2019 Prepared by Colin Plant Associates (UK) Consultant Entomologists 30a Alexandra Rd London N8 0PP 1 1 INTRODUCTION, BACKGROUND AND METHODOLOGY 1.1 Introduction and background 1.1.1 On 30th May 2018 Colin Plant Associates (UK) were commissioned by Biodiversity Team Manager, Karen Sutton on behalf of Thames Water Utilities Ltd. to undertake aquatic invertebrate sampling at Crossness Sewage Treatment Works on Erith Marshes, Kent. This survey was to mirror the locations and methodology of a previous survey undertaken during autumn 2016 and spring 2017. Colin Plant Associates also undertook the aquatic invertebrate sampling of this previous survey. 1.1.2 The 2016-17 aquatic survey was commissioned with the primary objective of establishing a baseline aquatic invertebrate species inventory and to determine the quality of the aquatic habitats present across both the Nature Reserve and Southern Marsh areas of the Crossness Sewage Treatment Works. The surveyors were asked to sample at twenty-four, pre-selected sample station locations, twelve in each area. Aquatic Coleoptera and Heteroptera (beetles and true bugs) were selected as target groups. A report of the previous survey was submitted in Sept 2017 (Plant 2017). 1.1.3 During December 2017 a large-scale pollution event took place and untreated sewage escaped into a section of the Crossness Nature Reserve. The primary point of egress was Nature Reserve Sample Station 1 (NR1) though because of the connectivity of much of the waterbody network on the marsh other areas were affected. -

Can Peatland Landscapes in Indonesia Be Drained Sustainably? an Assessment of the ‘Eko-Hidro’ Water Management Approach

Peatland Brief Can Peatland Landscapes in Indonesia be Drained Sustainably? An Assessment of the ‘eko-hidro’ Water Management Approach Peatland Brief Can Peatland Landscapes in Indonesia be Drained Sustainably? An Assessment of the ‘eko-hidro’ Water Management Approach July, 2016 Under the projects Indonesia Peatland Support Project (IPSP) funded by CLUA Sustainable Peatland for People and Climate (SPPC) funded by Norad To be cited as: Wetlands International, Tropenbos International, 2016. Can Peatland Landscapes in Indonesia be Drained Sustainably? An Assessment of the ‘Eko-Hidro’ Water Management Approach. Wetlands International Report. Table of Contents Table of Contents ........................................................................................................................... iii List of Tables .................................................................................................................................... iv List of Figure ..................................................................................................................................... iv Summary ........................................................................................................................................... iii 1. Introduction ............................................................................................................................. 1 2. The ‘eko-hidro’ peatland management approach and the Kampar HCV Assessment ............................................................................................................................. -

Additions, Deletions and Corrections to the Staphylinidae in the Irish Coleoptera Annotated List, with a Revised Check-List of Irish Species

Bulletin of the Irish Biogeographical Society Number 41 (2017) ADDITIONS, DELETIONS AND CORRECTIONS TO THE STAPHYLINIDAE IN THE IRISH COLEOPTERA ANNOTATED LIST, WITH A REVISED CHECK-LIST OF IRISH SPECIES Jervis A. Good1 and Roy Anderson2 1Glinny, Riverstick, Co. Cork, Republic of Ireland. e-mail: <[email protected]> 21 Belvoirview Park, Belfast BT8 7BL, Northern Ireland. e-mail: <[email protected]> Abstract Since the 1997 Irish Coleoptera – a revised and annotated list, 59 species of Staphylinidae have been added to the Irish list, 11 species confirmed, a number have been deleted or require to be deleted, and the status of some species and names require correction. Notes are provided on the deletion, correction or status of 63 species, and a revised check-list of 710 species is provided with a generic index. Species listed, or not listed, as Irish in the Catalogue of Palaearctic Coleoptera (2nd edition), in comparison with this list, are discussed. The Irish status of Gabrius sexualis Smetana, 1954 is questioned, although it is retained on the list awaiting further investgation. Key words: Staphylinidae, check-list, Irish Coleoptera, Gabrius sexualis. Introduction The Staphylinidae (rove-beetles) comprise the largest family of beetles in Ireland (with 621 species originally recorded by Anderson, Nash and O’Connor (1997)) and in the world (with 55,440 species cited by Grebennikov and Newton (2009)). Since the publication in 1997 of Irish Coleoptera - a revised and annotated list by Anderson, Nash and O’Connor, there have been a large number of additions (59 species), confirmation of the presence of several species based on doubtful old records, a number of deletions and corrections, and significant nomenclatural and taxonomic changes to the list of Irish Staphylinidae.