Uthongathi EMP: Situation Assessment Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ETHEKWINI MEDICAL HEALTH Facilitiesmontebellomontebello Districtdistrict Hospitalhospital CC 88 MONTEBELLOMONTEBELLO

&& KwaNyuswaKwaNyuswaKwaNyuswa Clinic ClinicClinic MontebelloMontebello DistrictDistrict HospitalHospital CC 88 ETHEKWINI MEDICAL HEALTH FACILITIESMontebelloMontebello DistrictDistrict HospitalHospital CC 88 MONTEBELLOMONTEBELLO && MwolokohloMwolokohlo ClinicClinic (( NdwedweNdwedweNdwedwe CHC CHCCHC && GcumisaGcumisa ClinicClinic CC MayizekanyeMayizekanye ClinicClinic BB && && ThafamasiThafamasiThafamasi Clinic ClinicClinic WosiyaneWosiyane ClinicClinic && HambanathiHambanathiHambanathi Clinic ClinicClinic && (( TongaatTongaatTongaat CHC CHCCHC CC VictoriaVictoriaVictoria Hospital HospitalHospital MaguzuMaguzu ClinicClinic && InjabuloInjabuloInjabuloInjabulo Clinic ClinicClinicClinic A AAA && && OakfordOakford ClinicClinic OsindisweniOsindisweni DistrictDistrict HospitalHospital CC EkukhanyeniEkukhanyeniEkukhanyeni Clinic ClinicClinic && PrimePrimePrime Cure CureCure Clinic ClinicClinic && BuffelsdraaiBuffelsdraaiBuffelsdraai Clinic ClinicClinic && RedcliffeRedcliffeRedcliffe Clinic ClinicClinic && && VerulamVerulamVerulam Clinic ClinicClinic && MaphephetheniMaphephetheni ClinicClinic AA &’&’ ThuthukaniThuthukaniThuthukani Satellite SatelliteSatellite Clinic ClinicClinic TrenanceTrenanceTrenance Park ParkPark Clinic ClinicClinic && && && MsunduzeMsunduze BridgeBridge ClinicClinic BB && && WaterlooWaterloo ClinicClinic && UmdlotiUmdlotiUmdloti Clinic ClinicClinic QadiQadi ClinicClinic && OttawaOttawa ClinicClinic && &&AmatikweAmatikweAmatikwe Clinic ClinicClinic && CanesideCanesideCaneside Clinic ClinicClinic AmaotiAmaotiAmaoti Clinic -

230 South Beach Road, La Mercy

LANDMARK INDIAN OCEAN BEACH HOTEL 230 SOUTH BEACH ROAD, LA MERCY WEB#: AUCT-000854 | www.in2assets.com ADDRESS: 230 South Beach Road, La Mercy AUCTION VENUE: The Durban Country Club, Isaiah Ntshangase Road, Durban AUCTION DATE & TIME: 07 February 2019 | 11h00 VIEWING: By Appointment CONTACT: Luke Hearn | 071 351 8138 | 031 574 7600 | [email protected] REGISTRATION FEE: R 50 000-00 (Refundable Bank Guaranteed Cheque) AUCTIONEER: Andrew Miller CONTENTS 230 SOUTH BEACH ROAD, LA MERCY 1318 Old North Coast Road, Avoca CPA LETTER 2 PROPERTY DESCRIPTION 3 PROPERTY LOCATION 4 PICTURE GALLERY 5 ADDITIONAL INFORMATION 12 TERMS AND CONDITIONS 14 SG DIAGRAMS 15 TITLE DEED 19 ZONING CERTIFICATE 28 BUILDING PLANS 31 LICENCES 38 DISCLAIMER: Whilst all reasonable care has been taken to provide accurate information, neither In2assets Properties (Pty) Ltd nor the Seller/s guarantee the correctness of the information, provided herein and neither will be held liable for any direct or indirect damages or loss, of whatsoever nature, suffered by any person as a result of errors or omissions in the information provided, whether due to the negligence or otherwise of In2assets Properties (Pty) Ltd or the Sellers or any other person. The Consumer Protection Regulations as well as the Rules of Auction can be viewed at www.In2assets.com or at Unit 504, 5th Floor, Strauss Daly Place, 41 Richefond Circle, Ridgeside Office Park, Umhlanga Ridge. Bidders must register to bid and provide original proof of identity and residence on registration. Version V4: 17.01.2019 1 CPA LETTER 230 SOUTH BEACH ROAD, LA MERCY 1318 Old North Coast Road, Avoca In2Assets would like to offer you, our valued client, the opportunity to pre-register as a bidder prior to the auction day. -

Promoting Green Urban Development in African Cities

Public Disclosure Authorized Promoting Green Urban Development in African Cities ETHEKWINI, SOUTH AFRICA Urban Environmental Profile Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Promoting Green Urban Development in African Cities ETHEKWINI, SOUTH AFRICA Urban Environmental Profile COPYRIGHT © 2016 International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank 1818 H Street NW Washington DC 20433 Telephone: 202-473-1000 Internet: www.worldbank.org This work is a product of the staff of The World Bank with external contributions. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this work do not necessarily reflect the views of The World Bank, its Board of Executive Directors, or the governments they represent. The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. The boundaries, colors, denominations, and other information shown on any map in this work do not imply any judgment on the part of The World Bank concerning the legal status of any territory or the endorsement or acceptance of such boundaries. February 2016 RIGHTS AND PERMISSIONS The material in this work is subject to copyright. Because The World Bank encourages dissemination of its knowledge, this work may be reproduced, in whole or in part, for noncommercial purposes as long as full attribution to this work is given. Any queries on rights and licenses, including subsidiary rights, should be addressed to the Publishing and Knowledge Division, The World Bank Group, 1818 H Street NW, Washington, DC 20433, USA; fax: 202-522-2625; e-mail: [email protected]. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The Promoting Green Urban Development in African Cities, Urban Environmental Profile for eThekwini, South Africa was prepared by a core study team led by Roland White (Global Lead: City Management, Governance and Financing - Task Team Leader) and included Chyi-Yun Huang (Urban Specialist) and a consultant team from AECOM including John Bachmann, Diane Dale, Brian Goldberg, Maritza Pechin and Dr. -

North Spatial Development Plan

North Spatial Development Plan Final Report 2013 / 2014 Review Review 4 of 4 North Spatial Development Plan (2013/14 Review) 1 1 CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY AND ACRONYMS 1 NORTHERN SPATIAL DEVELOPMENT PLAN ....................................................................... 6 1.1 Introduction.................................................................................................................................... 6 1.2 The SDP Process .......................................................................................................................... 6 1.3 The Focus Of The 2013/14 Review ............................................................................................... 7 1.4 Current Planning In The eThekwini Municipality ............................................................................ 8 1.5 Scope and Purpose of the Northern SDP ...................................................................................... 9 1.6 Geographic Location Of The Northern Region ............................................................................. 10 1.7 Demographic Profile .................................................................................................................... 11 2 METROPOLITAN SPATIAL DEVELOPMENT APPROACH ................................................... 15 2.1 Introduction.................................................................................................................................. 15 2.2 The Spatial Nature of Human Settlements .................................................................................. -

Consultation Basic Assessment Report for the Proposed Sibaya

REPORT Consultation Basic Assessment Report for the Proposed Sibaya Bulk Waterline from the Waterloo Reservoir to the Sibaya Precinct in eThekwini Metropolitan Municipality, KwaZulu- Natal Client: Tongaat Hulett Developments Reference: W01.RDC.000052 Revision: 01/Draft Date: 22 April 2016 Project related ROYAL HASKONINGDHV (PTY) LTD 6 Payne Street Pinetown Durban 3610 Transport & Planning Reg No. 1966/001916/07 +27 31 719 5500 T +27 31 719 5505 F [email protected] E royalhaskoningdhv.com W Document title: Consultation Basic Assessment Report for the Proposed Sibaya Bulk Waterline from the Waterloo Reservoir to the Sibaya Precinct in eThekwini Metropolitan Municipality, KwaZulu-Natal Document short title: Sibaya Waterline CBAR Reference: W01.RDC.000052 Revision: 01/Draft Date: 22 April 2016 Project name: W01.RDC.000052 Project number: W01.RDC.000052 Author(s): Humayrah Bassa Drafted by: Humayrah Bassa Pr.Sci.Nat. Checked by: Prashika Reddy Pr.Sci.Nat. Date / initials: 15.04.2016 Approved by: Prashika Reddy Pr.Sci.Nat. Date / initials: 15.04.2016 Classification Project related Disclaimer No part of these specifications/printed matter may be reproduced and/or published by print, photocopy, microfilm or by any other means, without the prior written permission of Royal HaskoningDHV (Pty) Ltd; nor may they be used, without such permission, for any purposes other than that for which they were produced. Royal HaskoningDHV (Pty) Ltd accepts no responsibility or liability for these specifications/printed matter to any party other than the persons by whom it was commissioned and as concluded under that Appointment. The quality management system of Royal HaskoningDHV (Pty) Ltd has been certified in accordance with ISO 9001, ISO 14001 and OHSAS 18001. -

Kwazulu-Natal Road Traffic Inspectorate Contact List

KWAZULU-NATAL ROAD TRAFFIC INSPECTORATE CONTACT LIST REGION / REG. CHIEF / S.C. TEL / FAX ADDRESS PHYSICAL STATION COMM SHORT ADDRESS HEAD OFFICE JM SCHNELL 033-3558880 033-3942979 P/Bag 9043 172 Burger Street MANAGER 0836444057 PMBurg PMBurg 3200 MR BW DAVIS 033-3550420 033-3942979 P/Bag 9043 172 Burger Street COM MANDER OPERATIONS 0836361151 PMBurg PMBurg 3200 R LAUBSCHER 033-3550464 033-3942979 P/Bag 9043 224 Prince COMMANDER INSPECTIONS 0828078715 PMBurg Alfred Street 3200 PMBurg TRAFFIC RB DU PLESSIS 033-3940202 033-3427711 P/Bag 9065 225 Prince TRAINING PMBurg 3200 Alfred Street COLLEGE PMBurg CJ KNOESEN 033-3940202 033-3427711 P/Bag 9065 225 Prince PMBurg 3200 Alfred Street PMBurg INFORMATION JZ MNGOMEZULU 033-3550442 033-3949684 P/Bag 9043 172 Burger Street OFFICER 0828081733 033-3550520 033-3949684 PMBurg PMBurg PL NTULI 3200 0829077984 INFORMATION MS L NTULI 033-3550442 033-3942979 P/Bag 9043 172 Burger Street OFFICER PMBurg PMBurg CHIEF RAJEN CHINABOO 033-3550418 033-3424126 P/Bag 9043 172 Burger Street PROVINCIAL 0836311286 PMBurg PMBurg INSPECTOR 3200 CHIEF TR GOVENDER 033-3550424 033-3424126 P/Bag 9043 172 Burger Street PROVINCIAL 0829065311 PMBurg 3200 PMBurg INSPECTOR PUBLIC MR MH NZIMAKWE 033 – 3558826 033 - 3558942 P/Bag X9043 172 Burger Street TRANSPORT (ACTING DD: PTEU) 033-3414500 PMBurg, 3200 PMBurg ENFORCE- 0829038925 MENT UNIT EMPANGENI 035-7871442/5/7 035-7871449 P/Bag X20031 Cnr Copper & REGIONAL L MTAMBO Empangeni Ngwezane Rd DIRECTOR 3380 Lot 00201 EMPANGENI ET ZULU 035-7871442/5/7 035-7871449 P/Bag 20031 Cnr -

Nacsa Newsletter Dec 2010

www.nacsa.org.za THE GUINEAFOWL NEWSLETTER NO 2 – 2010 Message from the editor I apologise for the delay with e-newsletter Number 2 of 2010. My home was burgled early Chairman’s chatter October with the newsletter 90% ready. My laptop was stolen and my last backup was not 100% Apologies on missing the deadline for the previous issue. I would like to successful and I lost everything back to July 2009. thank those who attended a very constructive AGM. Unfortunately alloca- What a disaster! tion of time sometimes is a problem due to the Seminar programme. There I am concerned to hear at times that the were suggestions for a full day but in discussion afterwards there was e-newsletter is not getting to all members. We opposition to this but we will discuss it in committee. Need feedback. only e-mail to the Chairperson or secretary and expect them to forward to all their members. We try to keep the newsletter to about 1,200KB with In 2009 we made a decision to formulate a strategy for KZNCA to give us articles about 300 words and all photos on a low direction. We were not happy with a number of issues of our service to resolution. We are often asked what does the our members. This process was completed the weekend prior to the AGM KZNCA do for conservancies or what do we get for the initial workshop held up in Kamberg in November 2009 followed by the R200 yearly fee? This e-newsletter is an Umgeni Valley mid-May 2010. -

Following Is a Load Shedding Schedule That People Are Advised to Keep

Following is a load shedding schedule that people are advised to keep. STAND-BY LOAD SHEDDING SCHEDULE Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday Sunday Block A 04:00-06:30 08:00-10:30 04:00-06:30 08:00-10:30 04:00-06:30 08:00-10:30 08:00-10:30 Block B 06:00-08:30 14:00-16:30 06:00-08:30 14:00-16:30 06:00-08:30 14:00-16:30 14:00-16:30 Block C 08:00-10:30 16:00-18:30 08:00-10:30 16:00-18:30 08:00-10:30 16:00-18:30 16:00-18:30 Block D 10:00-12:30 12:00-14:30 10:00-12:30 12:00-14:30 10:00-12:30 12:00-14:30 12:00-14:30 Block E 12:00-14:30 10:00-12:30 12:00-14:30 10:00-12:30 12:00-14:30 10:00-12:30 10:00-12:30 Block F 14:00-16:30 18:00-20:30 14:00-16:30 18:00-20:30 14:00-16:30 18:00-20:30 18:00-20:30 Block G 16:00-18:30 20:00-22:30 16:00-18:30 20:00-22:30 16:00-18:30 20:00-22:30 20:00-22:30 Block H 18:00-20:30 04:00-06:30 18:00-20:30 04:00-06:30 18:00-20:30 04:00-06:30 04:00-06:30 Block J 20:00-22:30 06:00-08:30 20:00-22:30 06:00-08:30 20:00-22:30 06:00-08:30 06:00-08:30 Area Block Albert Park Block D Amanzimtoti Central Block B Amanzimtoti North Block B Amanzimtoti South Block B Asherville Block H Ashley Block J Assagai Block F Athlone Block G Atholl Heights Block J Avoca Block G Avoca Hills Block C Bakerville Gardens Block G Bayview Block B Bellair Block A Bellgate Block F Belvedere Block F Berea Block F Berea West Block F Berkshire Downs Block E Besters Camp Block F Beverly Hills Block C Blair Atholl Block J Blue Lagoon Block D Bluff Block E Bonela Block E Booth Road Industrial Block E Bothas Hill Block F Briardene Block G Briardene -

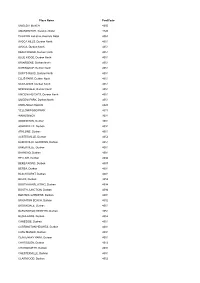

Place Name Postcode UMDLOTI BEACH 4350 AMANZIMTOTI

Place Name PostCode UMDLOTI BEACH 4350 AMANZIMTOTI, Kwazulu Natal 4126 PHOENIX Industria, Kwazulu Natal 4068 AVOCA HILLS, Durban North 4051 AVOCA, Durban North 4051 BEACHWOOD, Durban North 4051 BLUE RIDGE, Durban North 4051 BRIARDENE, Durban North 4051 DORINGKOP, Durban North 4051 DUFF'S ROAD, Durban North 4051 ELLIS PARK, Durban North 4051 NEWLANDS, Durban North 4051 SPRINGVALE, Durban North 4051 UMGENI HEIGHTS, Durban North 4051 UMGENI PARK, Durban North 4051 UMHLANGA ROCKS 4320 YELLOWWOOD PARK 4011 WANDSBECK 3631 ADDINGTON, Durban 4001 ASHERVILLE, Durban 4091 ATHLONE, Durban 4051 AUSTERVILLE, Durban 4052 BAKERVILLE GARDENS, Durban 4051 BAKERVILLE, Durban 4051 BAYHEAD, Durban 4001 BELLAIR, Durban 4094 BEREA ROAD, Durban 4007 BEREA, Durban 4001 BLACKHURST, Durban 4001 BLUFF, Durban 4052 BOOTH AANSLUITING, Durban 4094 BOOTH JUNCTION, Durban 4094 BOTANIC GARDENS, Durban 4001 BRIGHTON BEACH, Durban 4052 BROOKDALE, Durban 4051 BURLINGTON HEIGHTS, Durban 4051 BUSHLANDS, Durban 4052 CANESIDE, Durban 4051 CARRINGTON HEIGHTS, Durban 4001 CATO MANOR, Durban 4091 CENTENARY PARK, Durban 4051 CHATSGLEN, Durban 4012 CHATSWORTH, Durban 4092 CHESTERVILLE, Durban 4001 CLAIRWOOD, Durban 4052 CLARE Est/Lgd, Durban 4091 CLAYFIELD, Durban 4051 CONGELLA, Durban 4001 DALBRIDGE, Durban 4001 DORMERTON, Durban 4091 DURBAN NORTH, Durban 4051 DURBAN-NOORD, Durban 4051 Durban International Airport, Durban 4029 EARLSFIELD, Durban 4051 EAST END, Durban 4018 EASTBURY, Durban 4051 EFFINGHAM HEIGHTS, Durban 4051 FALLODEN PARK, Durban 4094 FLORIDA ROAD, Durban 4019 FOREST -

Critique of the Umdloti Town Planning Scheme

CRITIQUE OF THE UMDLOTI TOWNPLANNING SCHEME CRITIQUE OF THE UMDLOTI TOWNPLANNING SCHEME by MRlDULEKHA ALLOPI Submitted in partialfulfilment for the Degree ofMaster ofTown and Regional Planning, University ofNatal, Durban. Exceptfor quotations specifically indicated in the text, and any other help which is acknowledged, this dissertation is entirely my own work and has not been submitted for a degree in any other University. MRIDULEKHA ALLOPI December 2000 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS In preparing this Dissertation, I wish to convey my sincere thanks and appreciation to the following individuals: 1. My husband, Thivesh, for his continued support, patience and love over this pastyear; 2. My children, Nabeel and Adithi, for being so patient and understanding; 3. My parents, Rishi and Kam, sister and brother-in-law, Kamlesh and Koobashen, for all the words ofencouragement; 4. Rory Wilkinson, for his commitment and support; 5. Nathan Iyer, for his support and inspiration; 6. Kavi Soni, for his encouragement and support; 7. To all the staffofthe Planning and Environment Team ofthe North Local Councilfor all their support and continued encouragement; 8. To my Supervisor, Mike Khan, for guidance in preparing this Dissertation; and, 9. Last, but not least, to the Umdloti Ratepayers Association and all those equally important people who formed part ofthe information gathering process. Mridulekha Allopi December 2000 TABLE OF CONTENTS Pag;e No. CHAPTER ONE 1.0 Introduction 1 1.1 Locality ofthe Study Area 4 1.2 Topography 5 1.3 Background to the problem 5 1.4 -

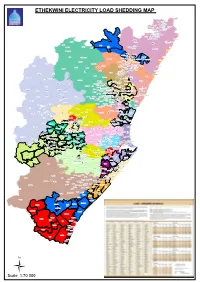

Ethekwini Electricity Load Shedding Map

ETHEKWINI ELECTRICITY LOAD SHEDDING MAP Lauriston Burbreeze Wewe Newtown Sandfield Danroz Maidstone Village Emona SP Fairbreeze Emona Railway Cottage Riverside AH Emona Hambanathi Ziweni Magwaveni Riverside Venrova Gardens Whiteheads Dores Flats Gandhi's Hill Outspan Tongaat CBD Gandhinagar Tongaat Central Trurolands Tongaat Central Belvedere Watsonia Tongova Mews Mithanagar Buffelsdale Chelmsford Heights Tongaat Beach Kwasumubi Inanda Makapane Westbrook Hazelmere Tongaat School Jojweni 16 Ogunjini New Glasgow Ngudlintaba Ngonweni Inanda NU Genazano Iqadi SP 23 New Glasgow La Mercy Airport Desainager Upper Bantwana 5 Redcliffe Canelands Redcliffe AH Redcliff Desainager Matata Umdloti Heights Nellsworth AH Upper Ukumanaza Emona AH 23 Everest Heights Buffelsdraai Riverview Park Windermere AH Mount Moreland 23 La Mercy Redcliffe Gragetown Senzokuhle Mt Vernon Oaklands Verulam Central 5 Brindhaven Riyadh Armstrong Hill AH Umgeni Dawncrest Zwelitsha Cordoba Gardens Lotusville Temple Valley Mabedlane Tea Eastate Mountview Valdin Heights Waterloo village Trenance Park Umdloti Beach Buffelsdraai Southridge Mgangeni Mgangeni Riet River Southridge Mgangeni Parkgate Southridge Circle Waterloo Zwelitsha 16 Ottawa Etafuleni Newsel Beach Trenance Park Palmview Ottawa 3 Amawoti Trenance Manor Mshazi Trenance Park Shastri Park Mabedlane Selection Beach Trenance Manor Amatikwe Hillhead Woodview Conobia Inthuthuko Langalibalele Brookdale Caneside Forest Haven Dimane Mshazi Skhambane 16 Lower Manaza 1 Blackburn Inanda Congo Lenham Stanmore Grove End Westham -

View GCE Brochure

This is living The depictions herein are for illustration purposes only and are subject to change without prior notice. Gold Coast Estate Open plan living TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 2-3 4-53 INTRODUCTION LOCATION GOLD COAST ESTATE 54-63 64-65 68-69 3D FLOOR PLANS PRICING & LEGAL FACT SHEET 72-77 80-83 DESIGN & FAQS ARCHITECTURAL GUIDELINES 1 Introducing Gold Coast Estate Sibaya From the developers of Ocean Dune Sibaya and Pebble Beach Sibaya comes the exceptional Gold Coast Estate. Set within KwaZulu-Natal’s sought-after Sibaya Coastal Precinct, this secure family estate is nestled between dense coastal forest and the golden sands of the North Coast. Gold Coast Estate offers architecturally-modern freestanding homes and sought-after recreational amenities set within a serene natural environment. The alluring beauty of Gold Coast Estate is mirrored by the exquisite natural exterior which offers an accessible network of walking, jogging and cycling trails. Many of the bespoke homes enjoy ocean vistas whilst others take full advantage of the majestic forest and dam views. Bordering Umdloti and Umhlanga, and just a stone’s throw away from Durban, Gold Coast Estate offers residents the comfort of an unsurpassed natural setting and the convenience of accessibility. This is natural living 2 Located within KZN’s premier node Gold Coast Estate is the preferred residence of discerning local and international investors. Situated on the burgeoning KwaZulu-Natal North Coast and near Umdloti, its location offers easy access to the natural tidal pool, open surf and golden beaches, all protected by the proactive Umdloti Conservancy overseen by the privately-funded Umdloti Improvement Project.