Promoting Green Urban Development in African Cities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ETHEKWINI MEDICAL HEALTH Facilitiesmontebellomontebello Districtdistrict Hospitalhospital CC 88 MONTEBELLOMONTEBELLO

&& KwaNyuswaKwaNyuswaKwaNyuswa Clinic ClinicClinic MontebelloMontebello DistrictDistrict HospitalHospital CC 88 ETHEKWINI MEDICAL HEALTH FACILITIESMontebelloMontebello DistrictDistrict HospitalHospital CC 88 MONTEBELLOMONTEBELLO && MwolokohloMwolokohlo ClinicClinic (( NdwedweNdwedweNdwedwe CHC CHCCHC && GcumisaGcumisa ClinicClinic CC MayizekanyeMayizekanye ClinicClinic BB && && ThafamasiThafamasiThafamasi Clinic ClinicClinic WosiyaneWosiyane ClinicClinic && HambanathiHambanathiHambanathi Clinic ClinicClinic && (( TongaatTongaatTongaat CHC CHCCHC CC VictoriaVictoriaVictoria Hospital HospitalHospital MaguzuMaguzu ClinicClinic && InjabuloInjabuloInjabuloInjabulo Clinic ClinicClinicClinic A AAA && && OakfordOakford ClinicClinic OsindisweniOsindisweni DistrictDistrict HospitalHospital CC EkukhanyeniEkukhanyeniEkukhanyeni Clinic ClinicClinic && PrimePrimePrime Cure CureCure Clinic ClinicClinic && BuffelsdraaiBuffelsdraaiBuffelsdraai Clinic ClinicClinic && RedcliffeRedcliffeRedcliffe Clinic ClinicClinic && && VerulamVerulamVerulam Clinic ClinicClinic && MaphephetheniMaphephetheni ClinicClinic AA &’&’ ThuthukaniThuthukaniThuthukani Satellite SatelliteSatellite Clinic ClinicClinic TrenanceTrenanceTrenance Park ParkPark Clinic ClinicClinic && && && MsunduzeMsunduze BridgeBridge ClinicClinic BB && && WaterlooWaterloo ClinicClinic && UmdlotiUmdlotiUmdloti Clinic ClinicClinic QadiQadi ClinicClinic && OttawaOttawa ClinicClinic && &&AmatikweAmatikweAmatikwe Clinic ClinicClinic && CanesideCanesideCaneside Clinic ClinicClinic AmaotiAmaotiAmaoti Clinic -

230 South Beach Road, La Mercy

LANDMARK INDIAN OCEAN BEACH HOTEL 230 SOUTH BEACH ROAD, LA MERCY WEB#: AUCT-000854 | www.in2assets.com ADDRESS: 230 South Beach Road, La Mercy AUCTION VENUE: The Durban Country Club, Isaiah Ntshangase Road, Durban AUCTION DATE & TIME: 07 February 2019 | 11h00 VIEWING: By Appointment CONTACT: Luke Hearn | 071 351 8138 | 031 574 7600 | [email protected] REGISTRATION FEE: R 50 000-00 (Refundable Bank Guaranteed Cheque) AUCTIONEER: Andrew Miller CONTENTS 230 SOUTH BEACH ROAD, LA MERCY 1318 Old North Coast Road, Avoca CPA LETTER 2 PROPERTY DESCRIPTION 3 PROPERTY LOCATION 4 PICTURE GALLERY 5 ADDITIONAL INFORMATION 12 TERMS AND CONDITIONS 14 SG DIAGRAMS 15 TITLE DEED 19 ZONING CERTIFICATE 28 BUILDING PLANS 31 LICENCES 38 DISCLAIMER: Whilst all reasonable care has been taken to provide accurate information, neither In2assets Properties (Pty) Ltd nor the Seller/s guarantee the correctness of the information, provided herein and neither will be held liable for any direct or indirect damages or loss, of whatsoever nature, suffered by any person as a result of errors or omissions in the information provided, whether due to the negligence or otherwise of In2assets Properties (Pty) Ltd or the Sellers or any other person. The Consumer Protection Regulations as well as the Rules of Auction can be viewed at www.In2assets.com or at Unit 504, 5th Floor, Strauss Daly Place, 41 Richefond Circle, Ridgeside Office Park, Umhlanga Ridge. Bidders must register to bid and provide original proof of identity and residence on registration. Version V4: 17.01.2019 1 CPA LETTER 230 SOUTH BEACH ROAD, LA MERCY 1318 Old North Coast Road, Avoca In2Assets would like to offer you, our valued client, the opportunity to pre-register as a bidder prior to the auction day. -

The Significance of Rural Areas in South Africa For

THE SIGNIFICANCE OF RURAL AREAS IN SOUTH AFRICA FOR TOURISM DEVELOPMENT THROUGH COMMUNITY PARTICIPATION WITH SPECIAL REFERENCE TO UMGABABA, A RURAL AREA LOCATED IN THE PROVINCE OF KWAZULU-NATAL by MOHAN GOPAUL Submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in the subject GEOGRAPHY at the UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH AFRICA SUPERVISOR: DR. A.C. HARMSE November 2006 ii Student number: 675-933-5 I declare that, “The significance of rural areas in South Africa for tourism development through community participation with special reference to Umgababa, a rural area located in the province of KwaZulu-Natal” is my own work and that all the sources that I have used or quoted have been indicated and acknowledged by means of complete references. ……………………… …………………. SIGNATURE DATE (MR. M. GOPAUL) iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my sincere gratitude to the following people whose contributions and support have been invaluable: Dr. A.C. Harmse, my supervisor for her superb supervision of the thesis. Ms. Melanie Nicolau, Head of Department, Department of Geography, Unisa, for her mediation in times of problems and continued assistance until completion of the thesis. Ms. Leanne Brown, subject librarian at Unisa, for her prompt service. Ms. Helenne Steenkamp, secretary at the Department of Geography, Unisa, for her prompt service with regards to communication. Ms. Noeline McNamara, from eThekwini Municipality, South Local Council, assisting with some of the maps. Radhika Gopaul (my wife) for typing and layout of the thesis. Arusha and Kerina (my daughters) for their continued support and patience during the writing process. Suren Bisseru, Simunye Printers, for binding this thesis. -

Kwazulu-Natal

PROVINCE PHYSICAL TOWN PHYSICAL SUBURB PHYSICAL ADDRESS PRACTICE NAME CONTACT NUMBER SPECIALITY PRACTICE NUMBER KWAZULU-NATAL AMANZIMTOTI AMANZIMTOTI 390 KINGSWAY ROAD JORDAN N 031 903 2335 GENERAL DENTAL PRACTICE 110752 KWAZULU-NATAL AMANZIMTOTI AMANZIMTOTI 388 KINGSWAY ROAD ESTERHUYSEN L 031 903 2351 GENERAL DENTAL PRACTICE 5417341 KWAZULU-NATAL AMANZIMTOTI AMANZIMTOTI 390 KINGSWAY ROAD BOTHA D H 031 903 2335 GENERAL DENTAL PRACTICE 5433169 KWAZULU-NATAL AMANZIMTOTI ATHLONE PARK 392 KINGS ROAD VAN DER MERWE D J 031 903 3120 GENERAL DENTAL PRACTICE 5440068 KWAZULU-NATAL AMANZIMTOTI WINKLESPRUIT 8A MURRAY SMITH ROAD OOSTHUIZEN K M 031 916 6625 GENERAL DENTAL PRACTICE 5451353 KWAZULU-NATAL ANERLEY SUNWICH PORT 6 ANERLEY ROAD KHAN M T 039 681 2670 GENERAL DENTAL PRACTICE 185914 KWAZULU-NATAL BERGVILLE TUGELA SQUARE TATHAM ROAD DR DN BLAKE 036 448 1112 GENERAL DENTAL PRACTICE 5430275 KWAZULU-NATAL BLUFF BLUFF 881 BLUFF ROAD Dr SIMONE DHUNRAJ 031 467 8515 GENERAL DENTAL PRACTICE 624292 KWAZULU-NATAL BLUFF FYNNLAND 19 ISLAND VIEW ROAD VALJEE P 031 466 1629 GENERAL DENTAL PRACTICE 5450926 KWAZULU-NATAL CHATSWORTH ARENA PARK 231 ARENA PARK ROAD Dr MAHENDRA ROOPLAL 031 404 8711 GENERAL DENTAL PRACTICE 5449049 KWAZULU-NATAL CHATSWORTH ARENA PARK 249 ARENA PARK ROAD LOKADASEN V 031 404 9095 DENTAL THERAPISTS 9500200 KWAZULU-NATAL CHATSWORTH CHATSWORTH 265 LENNY NAIDU ROAD DR D NAIDOO 031 400 0230 GENERAL DENTAL PRACTICE 116149 KWAZULU-NATAL CHATSWORTH CHATSWORTH 265 LENNY NAIDU ROAD DR K NAIDOO 031 400 0230 GENERAL DENTAL PRACTICE 116149 KWAZULU-NATAL -

Kwazulu-Natal Coastal Erosion Events of 2006/2007 And

Research Letter KwaZulu-Natal coastal erosion: A predictive tool? Page 1 of 4 KwaZulu-Natal coastal erosion events of 2006/2007 AUTHORS: and 2011: A predictive tool? Alan Smith' Lisa A. Guastella^ Severe coastal erosion occurred along the KwaZulu-Natal coastline between mid-May and November 2011. Andrew A. Mather^ Analysis of this erosion event and comparison with previous coastal erosion events in 2006/2007 offered the Simon C. Bundy" opportunity to extend the understanding of the time and place of coastal erosion strikes. The swells that drove Ivan D. Haigh* the erosion hotspots of the 2011 erosion season were relatively low (significant wave heights were between AFFILIATIONS: 2 m and 4.5 m) but ot long duration. Although swell height was important, swell-propagation direction and 'School of Geological Sciences, particularly swell duration played a dominant role in driving the 2011 erosion event. Two erosion hotspot types University of KwaZulu-Natal, were noted: sandy beaches underlain by shallow bedrock and thick sandy beaches. The former are triggered Durban, South Africa by high swells (as in March 2007) and austral winter erosion events (such as in 2006, 2007 and 2011). ^Oceanography Department, University of Cape Town, Cape The latter become evident later in the austral winter erosion cycle. Both types were associated with subtidal Town, South Africa shore-normal channels seaward of megacusps, themselves linked to megarip current heads. This 2011 ^Ethekwini Municipality, Durban, coastal erosion event occurred during a year in which the lunar perigee sub-harmonic cycle (a ±4.4-year South Africa cycle) peaked, a pattern which appears to have recurred on the KwaZulu-Natal coast. -

Case Study Metropolitan Governance Ethekwini

CASE STUDY METROPOLITAN GOVERNANCE ETHEKWINI (DURBAN), SOUTH AFRICA Authors Dr. Michael Sutcliffe and Ms. Sue Bannister www.cityinsight.co.za Coordination FMDV – Global Fund for Cities Development 35, Boulevard des Invalides 75007, Paris - France www.fmdv.net Commissioned by United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN-Habitat) Local Government and Decentralization Unit Urban Legislation, Land and Governance Branch P.O. Box 30030, 00100 Nairobi, GPO Kenya [email protected] www.unhabitat.org In collaboration with Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH Sector Project “Sustainable Development of Metropolitan Regions” Dag-Hammarskjöld-Weg 1-5 65760 Eschborn, Germany Tel. +49 (0) 6196 79 – 0 [email protected] www.giz.de This report was made possible thanks to the support of the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs to UN-Habitat. As at October 2015 Disclaimer The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers of boundaries. Views expressed by authors in this publication do not necessarily reflect those of the United Nations Human Settlements Programme, or the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH. Excerpts may be reproduced without authorisation, on condition that the source is indicated. 2 Case Study on Metropolitan Governance eThekwini (Durban), South Africa Dr. Michael Sutcliffe and Ms. Sue Bannister This metropolitan governance case study is part of a joint effort of GIZ and UN-Habitat to develop a framework for their future cooperation with metropolitan regions and related partners. -

List of Outstanding Trc Beneficiaries

List of outstanding tRC benefiCiaRies JustiCe inVites tRC benefiCiaRies to CLaiM tHeiR finanCiaL RePaRations The Department of Justice and Constitutional Development invites individuals, who were declared eligible for reparation during the Truth and Reconciliation Commission(TRC), to claim their once-off payment of R30 000. These payments will be eff ected from the President Fund, which was established in accordance with the Promotion of National Unity and Reconciliation Act and regulations outlined by the President. According to the regulations the payment of the fi nal reparation is limited to persons who appeared before or made statements to the TRC and were declared eligible for reparations. It is important to note that as this process has been concluded, new applications will not be considered. In instance where the listed benefi ciary is deceased, the rightful next-of-kin are invited to apply for payment. In these cases, benefi ciaries should be aware that their relationship would need to be verifi ed to avoid unlawful payments. This call is part of government’s attempt to implement the approved TRC recommendations relating to the reparations of victims, which includes these once-off payments, medical benefi ts and other forms of social assistance, establishment of a task team to investigate the nearly 500 cases of missing persons and the prevention of future gross human rights violations and promotion of a fi rm human rights culture. In order to eff ectively implement these recommendations, the government established a dedicated TRC Unit in the Department of Justice and Constitutional Development which is intended to expedite the identifi cation and payment of suitable benefi ciaries. -

ETHEKWINI MUNICIPALTY Water and Sanitation

EWS Planning of Water and Sanitation 13/02/2015 . Strategic Objectives . Legislation driving the business plan . Time horizon – Long term, medium term and short term plan – in terms in terms of legislated submission cycle . Beyond Urban Edge . Backlogs . Drought Strategic Objectives . Customer Perspective: Deliver quality and affordable services to our customers and customers take good care of the infrastructure. Financial Perspective: Achieve financial sustainability (sustainable tariffs, controlling costs, increased allocation of grants, etc.). Process Perspective: . Deliver fast, efficient, and effective service delivery (effective performance, removing constraints and bottlenecks, and improving efficiency). Ensure compliance to legislation and relevant governance prescripts (SCM, Environmental legislation, Health & Safety, etc.). Identify and effectively manage exposure to all risks. Achieve an unqualified audit. Organisational Capacity Perspective: . Ensure availability of adequate and appropriately skilled workforce. Sound (condition) and adequate (capacity) infrastructure to support current and future demand for water and sanitation services. Collaborate with relevant stakeholders to increase water resources sustainability. Legislations & Policies Driving the Business Plan . National Water Services Act . Water Supply Bylaws . Blue Drop certification requirements . Green Drop certification requirements . No Drop certification requirements . Environmental policies and Acts . Water Services Development Plan (WSDP) . Policies and Practices -

M Singhs Tours

M SINGHS TOURS 3) Services UMKOMAS/AMANZIMTOTI- DURBAN BUS TIMES TO DURBAN TRIP 1 FROM DURBAN TRIP 1 DEPOT 06.00 SALES HOUSE (441 WEST STREET) 16.22 EXEL GARAGE (ILLOV BEACH) 06.05 320 WEST STREET 16.30 SHIPS AHOY (ILLOVO BEACH) 06.08 KINGS HALL (ALIWAL) 16.33 PICK&PAY(WINKELSPRUIT) 06.10 DICK KING STATUE (VICTORIA EMBANKMENT) 16.37 TESTING STATION (WINKLE) 06.13 SPAR SHOPPING CENTRE (WARNER BEACH) 06.15 TOTAL GARAGE (WARNER BEACH) 06.18 SUN OFFICES (DOONSIDE) 06.22 ENGEN GARAGE (DOONSIDE) 06.23 KINGSWAY CAFE 06.27 SOUTHAGTE SHOPPING MALL 06.29 HIGH TIDE FLATS 06.31 BP CENTRE( GLORIA BAKERY) 06.33 POINTSETTIA PARK 06.35 SHOPING CENTRE (ATHLONE) 06.37 WEST STREET DURBAN (E.T.A) 07.15 UMZINTO- DURBAN BUS TIMES TO DURBAN TRIP 1 FROM DURBAN TRIP 1 SEZELA MAIN OFF RAMP 04.50 WORKSHOP(SOLIDERS WAY BUS RANK) 16.45 MALANGENI 04:55 BEREA MARKET 16.50 ESPERANZA 05.00 GALE STREET MORTUARY 16.51 UMZINTOMAIN ROAD 05.05 KING EDWARD HOSPITAL 16.53 RIVERSIDE ENTRANCE 05.10 ROSSBURGH MAIN ROAD 16.55 GHANDI NAGAR ENTRANCE 05.15 CLAIRWOOD SALES HOUSE 17.00 HAZELWOOD ENTRANCE 05.20 MONTCLAIR STATION 17.05 HYPERSINGH STORE 05.25 MOBENI(PASS McCARTHY) 17.10 TOTAL GARAGE( PARK RYNIE) 05.30 MEREBANK STATION 17.15 PILLAYS MOTOR SPARES 05.35 WERMA 17.20 SCOTTBURGH MALL 05.40 RANA ROAD 17.25 SCOTTBURGH HOSPITAL (ON HIGHWAY) 05.40 ISIPINGO STATION 17.30 UMKOMAAS OFF RAMP 05:45 JOYNER ROAD 17.35 PAVILLION, SUNCOAST, SIBAYA TOTI LOCALS TO GALLERIA TUESDAY AND THURSDAY PICK UP POINTS PICK UP TIMES PICK UP POINTS PICK UP SCOTTBURGH LIBRARY 08.10 ILLOVO BEACH VIA JABULANI, -

Name Corporate/Franchise Address Line 1 Address Line 2 Suburb

Name Corporate/Franchise Address Line 1 Address Line 2 Suburb Greater Area/City Province Main Phone GAUTENG Domino's Pizza Alberton Corporate 1 Venter St Shop 7, Jacqueline Mall Alberton Johannesburg Gauteng 011 908 3180 Domino's Pizza Bellairs Corporate Cnr Malibongwe & Bellairs Dr Shop 34, Bel Air Shopping Mall North Riding Johannesburg Gauteng 011 704 0907 Domino's Pizza Benoni Rynfield Corporate 178 Pretoria Rd Shop 2, Rynfield Shopping Centre Rynfield Benoni Gauteng 011 425 2101 Domino's Pizza Boksburg Corporate Cnr Rietfontein Rd & Rigg St Shop 2, The Square Shopping Centre Jansen Park Boksburg Gauteng 011 826 7013 Domino's Pizza Bonaero Park Franchise Cnr Tempelhof South St & Louis Botha Rd Shop 28, Aero Shopping Centre Bonaero Park Kempton Park Gauteng 011 973 1020 Domino's Pizza Brakpan Corporate 757 Voortrekker Rd Video Town, Brakpan Building Brakpan East Rand Gauteng 011 744 4723 Domino's Pizza Bram Fischer Blairgowrie Corporate 117 Bram Fischer Dr Shop 1, Canterbury Crossing Shopping Centre Blairgowrie Randburg Gauteng 011 326 1111 Domino's Pizza Bryan Park Corporate Cnr Grosvenor Rd & Cumberland Ave Shop 19A, Bryan Park Shopping Centre Bryanston Johannesburg Gauteng 011 463 2528 Domiono's Pizza Cherry Lane Corporate Cnr Fehrsen & Middel St Erf 437, Nieuw Muckleneuk Brooklyn Pretoria Gauteng 012 346 3599 Domino's Pizza Comaro Crossing Corporate Cnr Oak Stt Boundary Rd Shop FF21B Oakdene Gauteng 011 759 7269 Domino's Pizza Faerie Glen Corporate Cnr Solomon Mahlangu Dr & Haymeadow Cres Shop 4, Dischem Centre Faerie Glen Pretoria -

An Investigation Into Factors Increasing Contamination Risk Posed by Fuel Storage Facilities and Concomitant Methods to Mitigate These Risks

AN INVESTIGATION INTO FACTORS INCREASING CONTAMINATION RISK POSED BY FUEL STORAGE FACILITIES AND CONCOMITANT METHODS TO MITIGATE THESE RISKS by Torin Pfotenhauer BSc(Hons) University of Natal Submitted in fulfilment of the academic requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ENGINEERING in the School of Chemical Engineering University of KwaZulu-Natal Howard College DURBAN June 2011 - ii - As the candidates Supervisor, I agree / do not agree to the submission of this dissertation. Name______________________ Signature____________________ Date__________ - iii - ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The author acknowledges the following people for their invaluable contribution: Professor Chris Buckley for his extraordinary talent, open mind, insight and care. Dr Jennifer Pretorius who conceived the project. Kantey & Templer for unequivocal support. The Institute of Groundwater Studies from the University of the Free State who funded the project. The South African Petroleum Industry Association who supported the project. Chris Brouckaert who assisted with the data and statistics. Natalie Way-Jones who supported my endeavours. Dr Robert Palmer who sent the laughter down the passage during those late nights. Professor Glenda Matthews who unselfishly submerged herself in my project, understood my data nuances and led me through the data analysis and modelling. - iv - ABSTRACT Light Non-Aqueous Phase Liquids (LNAPLs) are used throughout the world for numerous applications, the most well-known being automotive fuels, such as petrol and diesel. The widespread production, distribution, storage and use of LNAPLs results in the ubiquitous occurrence of spillage to ground (Geller et al, 2000). Considering the hazardous nature of most LNAPLs due to their explosive and toxic characteristics, releases of LNAPLs to ground have well documented human health and ecological consequences. -

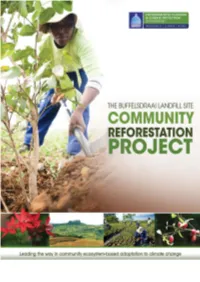

The Buffelsdraai Landfill Site Community Reforestation Project: Leading the Way in Community Ecosystem-Based Adaptation to Climate Change

Publication Details This document was produced and published by the Environmental Planning and Climate Protection Department of eThekwini Municipality, Durban, South Africa © 2015. Acknowledgements This document was produced by the eThekwini Municipality’s Environmental Planning and Climate Protection Department. Input was received from: Errol Douwes, Kathryn Roy, Nicci Diederichs-Mander, Khulile Mavundla and Debra Roberts. Suggested Citation Douwes, E., Roy, K.E., Diederichs-Mander, N., Mavundla, K., Roberts, D. 2015. The Buffelsdraai Landfill Site Community Reforestation Project: Leading the way in community ecosystem-based adaptation to climate change. eThekwini Municipality, Durban, South Africa. The following individuals are thanked for proofreading and provision of comments: Nokuphila Buthelezi, Joanne Douwes, Richard Boon, Joanne Lees, Benis Egoh, Nikara Mahadeo. Credits eThekwini Municipality, DANIDA and the National Green Fund are acknowledged for provision of funds. Photography Errol Douwes, Jon Ivins, Richard Boon Our Partners Architecture Department Design & layout Artworks | www.artworks.co.za Contents Foreword by Councillor James Nxumalo 2 Foreword by Ms Christiana Figueres 3 Foreword by Dr Debra Roberts 4 Introduction 5 Project Summary 6 The Climate Change Challenge 8 The Role of Forests 10 History of the Buff elsdraai Landfi ll Site 14 The Project Approach 15 How the Project has Changed People’s Lives 19 Advancing the Work of the Reforestation Project 22 Conclusion 26 Frequently Asked Questions 27 Further Reading and Information Resources 28 1 Foreword by Councillor James Nxumalo Mayor of eThekwini Municipality During the course of the past fi ve project, namely the Buff elsdraai years, eThekwini Municipality has Landfi ll Site Community Reforestation become a leader in the fi eld of climate Programme.