The Specificity of the Scripture's Canon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Book of Daniel and Its Canonical Variance: How a Hermeneutic of Wisdom Keeps the Book “Mobile”

1 The Book of Daniel and Its Canonical Variance: How a Hermeneutic of Wisdom Keeps the Book “Mobile” For an Old Testament book, Daniel exhibits some strange features. Given these features, it would clearly be an understatement to label the book, “mysterious.” Some enclaves of higher critical study have endeavored to organize these puzzling features in an attempt to solve them. But between allegations of pseudonimity, vaticinium ex eventu, bi-lingual constructions, late Greek additions, and a host of other supposed difficulties, we can understand Brevard Childs’s amazement that these critical endeavors have produced little theological fruit.1 However, one issue in the book of Daniel has the potential to bear such fruit. The canonical variance or “dual-placement” of Daniel in certain Old Testament arrangements (the Prophets in Greek/Latin orders and the Writings in the MT/Rabbinic orders) is a phenomenon that requires attention. I submit that the book of Daniel naturally fits in the Writings and that the book’s canonical shaping stands as a warrant for such placement. My initial approach to Daniel’s placement in the Hebrew canon requires two things. First, an assessment of the book in light of Old Testament canonical formation is essential, looking at proposed models and extra-biblical sources which accord Daniel the mantle of prophet. Next, we must assess the book’s canonical shaping: this includes a close look at a “hermeneutic of wisdom.” Based on these two assessments, we can better construe how Daniel might settle in the Writings, on both historical and theological grounds. I. THE BOOK OF DANIEL IN CANONICAL FORMATION 1. -

The Apocrypha1!Deuterocanonical Books: an Evangelical View

XIV lated widely in the Hellenistic church, many have argued that (a) the Septuagint represents an Alexandrian (as opposed to a Palestinian) canon, and that (b) the early church, using a Greek Bible, there fore clearly bought into this alternative canon. In any case, (c) the Hebrew canon was not "closed" until Jamnia (around 85 C.E.), so the earliest Christians could not have thought in terms of a closed Hebrew The Apocrypha1!Deuterocanonical Books: canon. "It seems therefore that the Protestant position must be judged a failure on historical grounds."2 An Evangelical View But serious objections are raised by traditional Protestants, including evangelicals, against these points. (a) Although the LXX translations were undertaken before Christ, the LXX evidence that has D. A. CARSON come down to us is both late and mixed. An important early manuscript like Codex Vaticanus (4th cent.) includes all the Apocrypha except 1 and 2 Maccabees; Codex Sinaiticus (4th cent.) has Tobit, Judith, Evangelicalism is on many points so diverse a movement that it would be presumptuous to speak of the 1 and 2 Maccabees, Wisdom, and Ecclesiasticus; another, Codex Alexandrinus (5th cent.) boasts all the evangelical view of the Apocrypha. Two axes of evangelical diversity are particularly important for the apocryphal books plus 3 and 4 Maccabees and the Psalms of Solomon. In other words, there is no evi subject at hand. First, while many evangelicals belong to independent and/or congregational churches, dence here for a well-delineated set of additional canonical books. (b) More importantly, as the LXX has many others belong to movements within national or mainline churches. -

Syllabus, Deuterocanonical Books

The Deuterocanonical Books (Tobit, Judith, 1 & 2 Maccabees, Wisdom, Sirach, Baruch, and additions to Daniel & Esther) Caravaggio. Saint Jerome Writing (oil on canvas), c. 1605-1606. Galleria Borghese, Rome. with Dr. Bill Creasy Copyright © 2021 by Logos Educational Corporation. All rights reserved. No part of this course—audio, video, photography, maps, timelines or other media—may be reproduced or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage or retrieval devices without permission in writing or a licensing agreement from the copyright holder. Scripture texts in this work are taken from the New American Bible, revised edition © 2010, 1991, 1986, 1970 Confraternity of Christian Doctrine, Washington, D.C. and are used by permission of the copyright owner. All Rights Reserved. No part of the New American Bible may be reproduced in any form without permission in writing from the copyright owner. 2 The Deuterocanonical Books (Tobit, Judith, 1 & 2 Maccabees, Wisdom, Sirach, Baruch, and additions to Daniel & Esther) Traditional Authors: Various Traditional Dates Written: c. 250-100 B.C. Traditional Periods Covered: c. 250-100 B.C. Introduction The Deuterocanonical books are those books of Scripture written (for the most part) in Greek that are accepted by Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox churches as inspired, but they are not among the 39 books written in Hebrew accepted by Jews, nor are they accepted as Scripture by most Protestant denominations. The deuterocanonical books include: • Tobit • Judith • 1 Maccabees • 2 Maccabees • Wisdom (also called the Wisdom of Solomon) • Sirach (also called Ecclesiasticus) • Baruch, (including the Letter of Jeremiah) • Additions to Daniel o “Prayer of Azariah” and the “Song of the Three Holy Children” (Vulgate Daniel 3: 24- 90) o Suzanna (Daniel 13) o Bel and the Dragon (Daniel 14) • Additions to Esther Eastern Orthodox churches also include: 3 Maccabees, 4 Maccabees, 1 Esdras, Odes (which include the “Prayer of Manasseh”) and Psalm 151. -

The Principal Works of St. Jerome by St

NPNF2-06. Jerome: The Principal Works of St. Jerome by St. Jerome About NPNF2-06. Jerome: The Principal Works of St. Jerome by St. Jerome Title: NPNF2-06. Jerome: The Principal Works of St. Jerome URL: http://www.ccel.org/ccel/schaff/npnf206.html Author(s): Jerome, St. Schaff, Philip (1819-1893) (Editor) Freemantle, M.A., The Hon. W.H. (Translator) Publisher: Grand Rapids, MI: Christian Classics Ethereal Library Print Basis: New York: Christian Literature Publishing Co., 1892 Source: Logos Inc. Rights: Public Domain Status: This volume has been carefully proofread and corrected. CCEL Subjects: All; Proofed; Early Church; LC Call no: BR60 LC Subjects: Christianity Early Christian Literature. Fathers of the Church, etc. NPNF2-06. Jerome: The Principal Works of St. Jerome St. Jerome Table of Contents About This Book. p. ii Title Page.. p. 1 Title Page.. p. 2 Translator©s Preface.. p. 3 Prolegomena to Jerome.. p. 4 Introductory.. p. 4 Contemporary History.. p. 4 Life of Jerome.. p. 10 The Writings of Jerome.. p. 22 Estimate of the Scope and Value of Jerome©s Writings.. p. 26 Character and Influence of Jerome.. p. 32 Chronological Tables of the Life and Times of St. Jerome A.D. 345-420.. p. 33 The Letters of St. Jerome.. p. 40 To Innocent.. p. 40 To Theodosius and the Rest of the Anchorites.. p. 44 To Rufinus the Monk.. p. 44 To Florentius.. p. 48 To Florentius.. p. 49 To Julian, a Deacon of Antioch.. p. 50 To Chromatius, Jovinus, and Eusebius.. p. 51 To Niceas, Sub-Deacon of Aquileia. -

The Lives of the Saints

Itl 1 i ill 11 11 i 11 i I 'M^iii' I III! II lr|i^ P !| ilP i'l ill ,;''ljjJ!j|i|i !iF^"'""'""'!!!|| i! illlll!lii!liiy^ iiiiiiiiiiHi '^'''liiiiiiiiilii ;ili! liliiillliili ii- :^ I mmm(i. MwMwk: llliil! ""'''"'"'''^'iiiiHiiiiiliiiiiiiiiiiiii !lj!il!|iilil!i|!i!ll]!; 111 !|!|i!l';;ii! ii!iiiiiiiiiiilllj|||i|jljjjijl I ili!i||liliii!i!il;.ii: i'll III ''''''llllllllilll III "'""llllllll!!lll!lllii!i I i i ,,„, ill 111 ! !!ii! : III iiii CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY l,wj Cornell Unrversity Library BR 1710.B25 1898 V.5 Lives ot the saints. Ili'lll I 3' 1924 026 082 572 Cornell University Library The original of tliis book is in tine Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924026082572 THE ilibes? of tlje t)atnt0 REV. S. BARING-GOULD SIXTEEN VOLUMES VOLUME THE FIFTH THE ILities of tlje g)amt6 BY THE REV. S. BARING-GOULD, M.A. New Edition in i6 Volumes Revised with Introduction and Additional Lives of English Martyrs, Cornish and Welsh Saints, and a full Index to the Entire Work ILLUSTRATED BY OVER 400 ENGRAVINGS VOLUME THE FIFTH LONDON JOHN C. NFMMO &-• NEW YORK . LONGMANS, GREEN. CO. MDCCCXCVIll / , >1< ^-Hi-^^'^ -^ / :S'^6 <d -^ ^' Printed by Ballantyne, Hanson &> CO. At the Ballantyne Press *- -»5< im CONTENTS PAGE Bernardine . 309 SS. Achilles and comp. 158 Boniface of Tarsus . 191 B. Alcuin 263 Boniface IV., Pope . 345 S. Aldhelm .... 346 Brendan of Clonfert 217 „ Alexander I., Pope . -

Cc 100: the Whole in One (The Whole Bible in One Quarter)

CREATION TO NEW CREATION: JOURNEY THROUGH SCRIPTURE FROM GENESIS TO REVELATION CC 100: THE WHOLE IN ONE (THE WHOLE BIBLE IN ONE QUARTER) Session 1 INTRODUCTION TO THE BIBLE: WHAT IT IS, HOW WE GOT IT, HOW TO READ IT, WHAT IT SAYS, HOW TO PRAY WITH IT 0. Introduction: Dare to Dream and The Task Before Us 0.1. “Can Catholics Be Bible Christians?: Debunking Some Popular Myths”–two-part article at www.emmausinstitute.net 0.2. Let’s think of the Bible as a Catholic book (because it is) and dream of the day when Catholic Christians are known as much by their devotion and attentiveness to consuming the words of our Lord as they are by their devotion and attentiveness to consuming the Word, the Body and Blood, of our Lord (see Dei Verbum 21). 0.3. The task before us in Session 1 1. What Is the Bible?: The Question of Definition 1.1. The Bible is a written text–pages with words written on them which someone wrote. a. Three essential elements of every written text: • a written medium (how it says) . • that conveys a message (what it says) . • for a particular mission someone wanted to accomplish (why it says). b. Illustration: A STOP sign c. When we go about reading or studying the Bible, these are the questions before us: • How does this text say what it is saying? (the medium/material) • What does this text say? (the meaning/message) • Why does this text say what it is saying? (the mission/motive) 1 2 1.2. -

A Commentary on Jerome's Contra Vigilantium by Amy

A COMMENTARY ON JEROME’S CONTRA VIGILANTIUM BY AMY HYE OH DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Classical Philology with a concentration in Medieval Studies in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2013 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Professor Danuta Shanzer Professor Ralph Mathisen Professor Jon Solomon Professor Stephan Heilan, University of Osnabrück ABSTRACT Innkeepers inspired this dissertation. After working on ‘innkeepers’ as a topic for a research seminar paper, I soon discovered that the term caupo counted as an insult according to several church fathers, including Jerome. In the Contra Vigilantium, Jerome mocked his enemy, Vigilantius, by calling him a caupo who mixed water with wine; I wondered whether the title was true and the insult was deserved. What remained was to figure out who this man was and why he mattered. The dissertation is comprised of four parts: introductory chapters, a text with an en face translation, a philological/historical commentary, and appendices. The first chapter introduces Vigilantius, discusses why a commentary of the Contra Vigilantium is needed, and provides a biography, supported by literary and historical evidence in response to the bolder and more fanciful account of W.S. Gilly.1 The second chapter treats Vigilantius as an exegete. From a sample of his exegesis preserved in Jerome’s Ep. 61, I determine that Jerome dismissed Vigilantius’ exegesis because he wanted to protect his own orthodoxy. The third chapter situates Vigilantius in the debate on relic worship. His position is valuable because he opposed most of his contemporaries, decrying relics instead of supporting their translation and veneration. -

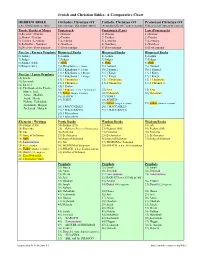

Hebrew and Christian Bibles: a Comparative Chart

Jewish and Christian Bibles: A Comparative Chart HEBREW BIBLE Orthodox Christian OT Catholic Christian OT Protestant Christian OT (a.k.a. TaNaK/Tanakh or Mikra) (based on longer LXX; various editions) (Alexandrian LXX, with 7 deutero-can. bks) (Cath. order, but 7 Apocrypha removed) Torah / Books of Moses Pentateuch Pentateuch (Law) Law (Pentateuch) 1) Bereshit / Genesis 1) Genesis 1) Genesis 1) Genesis 2) Shemot / Exodus 2) Exodus 2) Exodus 2) Exodus 3) VaYikra / Leviticus 3) Leviticus 3) Leviticus 3) Leviticus 4) BaMidbar / Numbers 4) Numbers 4) Numbers 4) Numbers 5) Devarim / Deuteronomy 5) Deuteronomy 5) Deuteronomy 5) Deuteronomy Nevi’im / Former Prophets Historical Books Historical Books Historical Books 6) Joshua 6) Joshua 6) Joshua 6) Joshua 7) Judges 7) Judges 7) Judges 7) Judges 8) Samuel (1&2) 8) Ruth 8) Ruth 8) Ruth 9) Kings (1&2) 9) 1 Kingdoms (= 1 Sam) 9) 1 Samuel 9) 1 Samuel 10) 2 Kingdoms (= 2 Sam) 10) 2 Samuel 10) 2 Samuel 11) 3 Kingdoms (= 1 Kings) 11) 1 Kings 11) 1 Kings Nevi’im / Latter Prophets 12) 4 Kingdoms (= 2 Kings) 12) 2 Kings 12) 2 Kings 10) Isaiah 13) 1 Chronicles 13) 1 Chronicles 13) 1 Chronicles 11) Jeremiah 14) 2 Chronicles 14) 2 Chronicles 14) 2 Chronicles 12) Ezekiel 15) 1 Esdras 13) The Book of the Twelve: 16) 2 Esdras (= Ezra + Nehemiah) 15) Ezra 15) Ezra Hosea, Joel, 17) Esther (longer version) 16) Nehemiah 16) Nehemiah Amos, Obadiah, 18) JUDITH 17) TOBIT Jonah, Micah, 19) TOBIT 18) JUDITH Nahum, Habakkuk, 19) Esther (longer version) 17) Esther (shorter version) Zephaniah, Haggai, 20) 1 MACCABEES 20) -

The Apocryphal/Deuterocanonical Books of the Old Testament

Adult Catechism April 11, 2016 The Apocryphal/Deuterocanonical Books of the Old Testament Part 1: Scripture Readings: Sirach 7: 1-3 : After If you do no wrong, no wrong will ever come to you. Do not plow the ground to plant seeds of injustice; you may reap a bigger harvest than you expect. Baruch 1:15-21: This is the confession you should make: The Lord our God is righteous, but we are still covered with shame. All of us—the people of Judah, the people of Jerusalem, our kings, our rulers, our priests, our prophets, and our ancestors have been put to shame, because we have sinned against the Lord our God and have disobeyed him. We did not listen to him or live according to his commandments. From the day the Lord brought our ancestors out of Egypt until the present day, we have continued to be unfaithful to him, and we have not hesitated to disobey him. Long ago, when the Lord led our ancestors out of Egypt, so that he could give us a rich and fertile land, he pronounced curses against us through his servant Moses. And today we are suffering because of those curses. We refused to obey the word of the Lord our God which he spoke to us through the prophets. Instead, we all did as we pleased and went on our own evil way. We turned to other gods and did things the Lord hates. Part 2: What are the Apocryphal/Deuterocanonical Books of the Old Testament?: The word “Apocrypha” means “hidden” and can refer to books meant only for the inner circle, or books not good enough to be read, or simply books outside of the canon. -

Professor Stokes' 'Ireland and Celtic Church'

210 Professor Stokes' "Ireland and the Celtic Church." bring painful perplexity to the occupant of the throne; bl!t through the Divine blessing, and the Monarch's confidence m the people the clouds have dispersed. It is meet, therefore, that after 'fiftyyears of mutual confid~n_?e, of trials and. of triumphs, Queen and people should reJOICe together durmg this year of jubilee. A LAYMAN. -.--<>~¢--- ART. VII.-PROFESSOR STOKES' r" IRELAND AND THE CELTIC CHURCH." Irelmul cuul the Celtic Chtwch. A History of Ireland from St. Patrick to the English Conquest in 1172. By Rev. GEORGE T. STOKES, D.D, Vicar of All Saints, Blackrock; Professor of Ecclesiastical History, Trinity College, Dublin. Hodder and Stoughton, Paternoster Row. HE name of "Silent Sister," which used to be reproach T fully applied to the Irish University, has happily of recent years been altogether undeserved. The classical publications of Mahaffy and Tyrrell ; Provost J ellett's "Sermons on the Efficacy of Prayer;" Dr. Salmon's " Introduction to the Study of the New Testament;" Mt. Barlow's "Ultimatum of Pes simism;" and now Professor Stokes' " Lectures on Irish Ecclesiastical History," are all indications of the productive power of Dublin University men in the various spheres wherein their special studies lie. We welcome Professor Stokes' work with great pleasure, because Irish history is comparatively little read; and the style of his lectures, learned though they are, is so lucid and readable, that it will naturally attract persons desirous of a better acquaintance with the subject to study it in his pleasant pages. As the title shows, the work covers the reriod from the arrival of St. -

The Septuagint As a Holy Text – the First 'Bible' of the Early Church

HTS Teologiese Studies/Theological Studies ISSN: (Online) 2072-8050, (Print) 0259-9422 Page 1 of 9 Original Research The Septuagint as a holy text – The first ‘bible’ of the early church Author: This article acknowledges the fact that historically there are two phases in the emergence of the 1 Johann Cook Septuagint – a Jewish phase and a Christian one. The article deals first with methodological Affiliation: issues. It then offers a historical orientation. In the past some scholars have failed to distinguish 1Department of Ancient between key historical phases: the pre-exilic/exilic (Israelite – 10 tribes), the exilic (the Studies, Faculty of Arts and Babylonian exile ‒ 2 tribes) and the post-exilic (Judaean/Jewish). Many scholars are unaware Social Sciences, University of of the full significance of the Hellenistic era, including the Seleucid and Ptolemaic eras and Stellenbosch, Stellenbosch, South Africa their impact on ‘biblical’ textual material. Others again overestimate the significance of this era; the Greek scholar Evangelia Dafni is an example. Many are uninformed about the Persian Corresponding author: era, which includes the Achaemenid, Parthian and Sassanian eras, each one of which had an Johann Cook, impact on Judaism. An example is the impact of Persian dualism. Another problem is the [email protected] application of the concept of ‘the Bible’. The notion of ‘Bible’ applies only after the 16th century Dates: Common Era, specifically after the advent of the printing press. Earlier, depending on the Received: 18 May 2020 context, we had clay tablets (Mesopotamia), vella (Levant-Judah) and papyri (Egypt) to write Accepted: 06 July 2020 on. -

R. Laird Harris, "Factors Promoting the Formation of the Old Testament

FACTORS PROMOTlNG THE FORMATION OF THE OLD TESTA}.fE;\.'T CANON R. L.\ 11\1) 1 h HHlS, PH.D. Extra-Biblical witness to tIl(' origin of the Old Testament books is lacking. There are no copies of lite Old Testament writings earlier than about 250 B.C. and no parallel ancien! literatmc referring to them. Only two sources are available, therefore, for tlte prescnt study: the claims of the Old Testamcnt for ito:clf, and tlte ild"alJihle teachings of Jesus Christ who, Christians believe, Lllew perfcL'/ II' all tIle facts. If the topic concerned the collection of the Olll Testament books and the acceptance of the Old Tcstament canon there would he a bit larger room for the investigation of post-Old Testament literature. Thanks to the Dead Sea discoveries and new knowledge of apocryphal books and similar literature one can trace back the recognition of some of the Old Testament books rather well. Still, the extra-Biblical witness fails to reach back to the Old Testament peliod. As to the formation of the Old Testament canon, historic Christianity insists that the Old Testament books were written by special divine in spiration. They therefore came with inherent authority and were accepted by the faithful in Israel at once as the Word of God. In short, the canon was formed over the centuries as the books were written under the in spiration of God. This view is usually thought of as the Protestant view, but the Roman Catholic Council of Trent and the Vatican Council I are in basic agree ment with it.