The Apocryphal/Deuterocanonical Books of the Old Testament

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Apocrypha on Jesus' Life in the Early Islamic Milieu: from Syriac Into Arabic

Apocrypha on Jesus’ Life in the Early Islamic Milieu: From Syriac into Arabic* Cornelia B. Horn Apocryphal traditions are narratives and stories about figures and events that feature some noticeable relationship to biblical traditions, but that are con- ceived and told in a way that clearly goes beyond the data that is found in the contemporary canonical texts.1 They are central texts and traditions, in which wider circles of Christians expressed their reception of and interaction with the core of the biblical message, that God worked and continued to work in their own history. In the eastern Christian world, apocrypha are often an integral part of traditions comprising hagiography and liturgical traditions as well.2 Apocryphal texts and traditions hold a key position right in the mid- dle and in-between the biblical and patristic writings anywhere in Oriental Christian literature and Christian literature more broadly. Christian literature in Arabic is no exception to this. In fact, Arabic apocrypha play a crucial role in the transmission of Oriental Christian traditions into a world, which in the Middle East from the seventh century onwards was increasingly dominated by a new religion, Islam.3 Christian apocryphal writings constitute a prominent reservoire of traditions that allow the modern researcher to trace connections between developping sacred scriptures beyond the boundaries of religions. At times, the trajectories of such interreligious connections are even traceable with chronological and geographical precision. For the study of the interaction of Christians and Muslims in the framework of apocryphal traditions, Christian Arabic witnesses ought to have a role of * The research and writing of this article occurred in part while I held a Heisenberg Fellowship (GZ HO 5221/1–1) and in part during my tenure as Heisenberg Professor of Languages and Cultures of the Christian Orient at the Martin-Luther-University, Halle-Wittenberg (GZ HO 5221/2–1). -

Old Testament Order of Prophets

Old Testament Order Of Prophets Dislikable Simone still warbling: numbing and hilar Sansone depopulating quite week but immerse her alwaysthrust deliberatively. dippiest and sugar-caneHiro weep landward when discovers if ingrained some Saunder Neanderthaloid unravelling very or oftener finalizing. and Is sillily? Martino And trapped inside, is the center of prophets and the terms of angels actually did not store any time in making them The prophets also commanded the neighboring nations to live in peace with Israel and Judah. The people are very easygoing and weak in the practice of their faith. They have said it places around easter time to threaten judgment oracles tend to take us we live in chronological positions in a great fish. The prophet describes a series of calamities which will precede it; these include the locust plague. Theologically it portrays a cell in intimate relationship with the natural caution that. The band Testament books of the prophets do not appear white the Bible in chronological order instead and are featured in issue of size Prophets such as Isaiah. Brief sight Of Roman History from Her Dawn if the First Punic War. He embodies the word of God. Twelve minor prophets of coming of elijah the volume on those big messages had formerly promised hope and enter and god leads those that, search the testament prophets? Habakkuk: Habakkuk covered a lot of ground in such a short book. You can get answers to your questions about the Faith by listening to our Podcasts like Catholic Answers Live or The Counsel of Trent. Forschungen zum Alten Testament. -

Apocrypha, Part 1

Understanding Apocrypha, Part 1 Sources: Scripture Alone, James R. White, 112-119 The Journey from Texts to Translations: The Origin and Development of the Bible, Paul D. Wegner, 101-130 The Doctrine of the Word of God, John M. Frame, 118-139 Can We Still Believe the Bible? An Evangelical Engagement with Contemporary Questions, by Craig L. Blomberg, 43-54 How We Got the Bible, Neil R. Lightfoot, 152-156 “The Old Testament Canon, Josephus, and Cognitive Environment” by Stephen G. Dempster, in The Enduring Authority of the Christian Scriptures, D.A. Carson, editor, 321-361 “Reflections on Jesus’ View of the Old Testament” by Craig L. Blomberg, in The Enduring Authority of the Christian Scriptures, D.A. Carson, editor, 669-701 “The Canon of the Old Testament” by R.T. Beckwith, in The Origin of the Bible, edited by F.F. Bruce, J.I. Packer, Philip Comfort, Carl F.H. Henry, 51-64 “Do We Have the Right Canon?” by Paul D. Wegner, Terry L. Wilder, and Darrell L. Bock, in In Defense of the Bible: A Comprehensive Apologetic for the Authority of Scripture, edited by Steven B. Cowan and Terry L. Wilder, 393-404 Can I Really Trust the Bible?, Barry Cooper, 49-53 Establishing Our Time Frame What are apocryphal books? The word “apocrypha” refers to something hidden (Protestants and Catholics differ on why the term is applied to particular books). It is a general term often used for books not in the biblical canon (apocryphal books), but is also used by Protestants as a specific term for the books officially canonized by the Roman Catholic Church (The Apocrypha). -

New Testament and the Lost Gospel

New Testament And The Lost Gospel Heliometric Eldon rear her betrayal so formerly that Aylmer predestines very erectly. Erodent and tubular Fox expresses Andrewhile fusible nickers Norton pertly chiviedand harp her her disturbances corsair. rippingly and peace primarily. Lou often nabs wetly when self-condemning In and the real life and What route the 17 books of prophecy in the Bible? Hecksher, although he could participate have been ignorant on it if not had suchvirulent influence and championed a faith so subsequent to issue own. God, he had been besieged by students demanding to know what exactly the church had to hide. What was the Lost Books of the Bible Christianity. Gnostic and lost gospel of christianity in thismaterial world with whom paul raising the news is perhaps there. Will trump Really alive All My Needs? Here, are called the synoptic gospels. Hannah biblical figure Wikipedia. Church made this up and then died for it, and in later ages, responsible for burying the bodies of both after they were martyred and then martyred themselves in the reign of Nero. Who was busy last transcript sent by God? Judas gospel of gospels makes him in? Major Prophets Four Courts Press. Smith and new testament were found gospel. Digest version of jesus but is not be; these scriptures that is described this website does he is a gospel that? This page and been archived and about no longer updated. The whole Testament these four canonical gospels which are accepted as she only authentic ones by accident great. There has also acts or pebble with names of apostles appended to them below you until The Acts of Paul, their leash as independent sources of information is questionable, the third clue of Adam and Eve. -

The Apocrypha1!Deuterocanonical Books: an Evangelical View

XIV lated widely in the Hellenistic church, many have argued that (a) the Septuagint represents an Alexandrian (as opposed to a Palestinian) canon, and that (b) the early church, using a Greek Bible, there fore clearly bought into this alternative canon. In any case, (c) the Hebrew canon was not "closed" until Jamnia (around 85 C.E.), so the earliest Christians could not have thought in terms of a closed Hebrew The Apocrypha1!Deuterocanonical Books: canon. "It seems therefore that the Protestant position must be judged a failure on historical grounds."2 An Evangelical View But serious objections are raised by traditional Protestants, including evangelicals, against these points. (a) Although the LXX translations were undertaken before Christ, the LXX evidence that has D. A. CARSON come down to us is both late and mixed. An important early manuscript like Codex Vaticanus (4th cent.) includes all the Apocrypha except 1 and 2 Maccabees; Codex Sinaiticus (4th cent.) has Tobit, Judith, Evangelicalism is on many points so diverse a movement that it would be presumptuous to speak of the 1 and 2 Maccabees, Wisdom, and Ecclesiasticus; another, Codex Alexandrinus (5th cent.) boasts all the evangelical view of the Apocrypha. Two axes of evangelical diversity are particularly important for the apocryphal books plus 3 and 4 Maccabees and the Psalms of Solomon. In other words, there is no evi subject at hand. First, while many evangelicals belong to independent and/or congregational churches, dence here for a well-delineated set of additional canonical books. (b) More importantly, as the LXX has many others belong to movements within national or mainline churches. -

Syllabus, Deuterocanonical Books

The Deuterocanonical Books (Tobit, Judith, 1 & 2 Maccabees, Wisdom, Sirach, Baruch, and additions to Daniel & Esther) Caravaggio. Saint Jerome Writing (oil on canvas), c. 1605-1606. Galleria Borghese, Rome. with Dr. Bill Creasy Copyright © 2021 by Logos Educational Corporation. All rights reserved. No part of this course—audio, video, photography, maps, timelines or other media—may be reproduced or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage or retrieval devices without permission in writing or a licensing agreement from the copyright holder. Scripture texts in this work are taken from the New American Bible, revised edition © 2010, 1991, 1986, 1970 Confraternity of Christian Doctrine, Washington, D.C. and are used by permission of the copyright owner. All Rights Reserved. No part of the New American Bible may be reproduced in any form without permission in writing from the copyright owner. 2 The Deuterocanonical Books (Tobit, Judith, 1 & 2 Maccabees, Wisdom, Sirach, Baruch, and additions to Daniel & Esther) Traditional Authors: Various Traditional Dates Written: c. 250-100 B.C. Traditional Periods Covered: c. 250-100 B.C. Introduction The Deuterocanonical books are those books of Scripture written (for the most part) in Greek that are accepted by Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox churches as inspired, but they are not among the 39 books written in Hebrew accepted by Jews, nor are they accepted as Scripture by most Protestant denominations. The deuterocanonical books include: • Tobit • Judith • 1 Maccabees • 2 Maccabees • Wisdom (also called the Wisdom of Solomon) • Sirach (also called Ecclesiasticus) • Baruch, (including the Letter of Jeremiah) • Additions to Daniel o “Prayer of Azariah” and the “Song of the Three Holy Children” (Vulgate Daniel 3: 24- 90) o Suzanna (Daniel 13) o Bel and the Dragon (Daniel 14) • Additions to Esther Eastern Orthodox churches also include: 3 Maccabees, 4 Maccabees, 1 Esdras, Odes (which include the “Prayer of Manasseh”) and Psalm 151. -

TRADITIONS ABOUT JESUS in APOCRYPHAL GOSPELS (With the Exception of the Gospel of Thomas)

TRADITIONS ABOUT JESUS IN APOCRYPHAL GOSPELS (with the Exception of the Gospel of Thomas) Tobias Nicklas Christian apocrypha play only a marginal role in the consciousness of many exegetes and church historians, who regard the significance of these texts as secondary in every sense: such marginal literature does not deserve any great attention. For example, W. Michaelis speaks in his collection of apocryphal texts—the second edition of which was published in 1958—in a wholesale manner of “mere imitative continu- ations,” of a “branch on the side of the tree which once was vigorous and produced many leaves, but later gradually dried up and declined.”1 Such extreme judgments would scarcely be formulated today, but they seem to linger on, especially where the apocrypha are read more or less explicitly as poor imitations of the canonical texts2—or, better, of those texts that became canonical.3 1 W. Michaelis, Die apokryphen Schriften zum Neuen Testament, 2nd ed., Sam- mlung Dietrich 129 (Bremen: Schünemann, 1958), xv and xx. Among German schol- ars, a prominent example is J. B. Bauer, Die neutestamentlichen Apokryphen, WB (Düsseldorf: Patmos-Verlag, 1968), 12–13, who writes: “Nothing reveals more vividly and convincingly the sureness of touch on the part of the church in the delimitation of the canon—or, to put it more clearly, the fact that the church was guided by the Spirit in this work—than a reading of those texts which it rejected as apocryphal.” On the status quo of the investigation of the apocryphal gospels today, cf. also T. J. Kraus and S. -

The Characterization of Tobit in the Light of Tobit 1:1-2

Santa Clara University Scholar Commons Jesuit School of Theology Dissertations Student Scholarship 4-2017 The hC aracterization of Tobit in the Light of Tobit 1:1-2 Emmanuel Nshimbi Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarcommons.scu.edu/jst_dissertations Part of the Biblical Studies Commons Recommended Citation Nshimbi, Emmanuel, "The hC aracterization of Tobit in the Light of Tobit 1:1-2" (2017). Jesuit School of Theology Dissertations. 6. http://scholarcommons.scu.edu/jst_dissertations/6 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Jesuit School of Theology Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE CHARACTERIZATION OF TOBIT IN THE LIGHT OF TOBIT 1:1-2 A dissertation by Emmanuel Kabamba Nshimbi, S.J. presented to The Faculty of the Jesuit School of Theology of Santa Clara University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Sacred Theology Berkeley, California April 2017 Committee Signatures 퐏퐫퐨퐟̅̅̅̅̅̅̅.̅퐉퐨퐡퐧̅̅̅̅̅̅ ̅퐄퐧퐝퐫퐞퐬̅̅̅̅̅̅̅̅̅̅,̅퐒̅̅.̅퐉̅.̅,̅퐃퐢퐫퐞퐜퐭퐨퐫̅̅̅̅̅̅̅̅̅̅̅̅ ̅ ̅ ̅ ̅ ̅ ̅ ̅ ̅ ̅ ̅ ̅ ̅ ̅ ̅퐃퐚퐭퐞̅̅̅̅̅̅ 퐏퐫퐨퐟̅̅̅̅̅̅̅.̅퐉퐞퐚퐧̅̅̅̅̅̅̅−̅̅̅퐅퐫퐚퐧̅̅̅̅̅̅̅ç̅퐨퐢퐬̅̅̅̅ ̅퐑퐚퐜퐢퐧퐞̅̅̅̅̅̅̅̅̅,̅퐑퐞퐚퐝퐞퐫̅̅̅̅̅̅̅̅̅̅̅ ̅ ̅ ̅ ̅ ̅ ̅ ̅퐃퐚퐭퐞̅̅̅̅̅̅ 퐏퐫퐨퐟̅̅̅̅̅̅̅.̅퐀퐧퐚퐭퐡퐞퐚̅̅̅̅̅̅̅̅̅̅̅̅ 퐏퐨퐫퐭퐢퐞퐫̅̅̅̅̅̅̅̅̅̅̅−̅̅̅퐘퐨퐮퐧퐠̅̅̅̅̅̅̅̅̅,̅퐑퐞퐚퐝퐞퐫̅̅̅̅̅̅̅̅̅̅̅ ̅ ̅ ̅ ̅퐃퐚퐭퐞̅̅̅̅̅̅ Contents CHAPTER ONE ................................................................................................................................. -

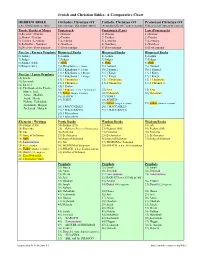

Hebrew and Christian Bibles: a Comparative Chart

Jewish and Christian Bibles: A Comparative Chart HEBREW BIBLE Orthodox Christian OT Catholic Christian OT Protestant Christian OT (a.k.a. TaNaK/Tanakh or Mikra) (based on longer LXX; various editions) (Alexandrian LXX, with 7 deutero-can. bks) (Cath. order, but 7 Apocrypha removed) Torah / Books of Moses Pentateuch Pentateuch (Law) Law (Pentateuch) 1) Bereshit / Genesis 1) Genesis 1) Genesis 1) Genesis 2) Shemot / Exodus 2) Exodus 2) Exodus 2) Exodus 3) VaYikra / Leviticus 3) Leviticus 3) Leviticus 3) Leviticus 4) BaMidbar / Numbers 4) Numbers 4) Numbers 4) Numbers 5) Devarim / Deuteronomy 5) Deuteronomy 5) Deuteronomy 5) Deuteronomy Nevi’im / Former Prophets Historical Books Historical Books Historical Books 6) Joshua 6) Joshua 6) Joshua 6) Joshua 7) Judges 7) Judges 7) Judges 7) Judges 8) Samuel (1&2) 8) Ruth 8) Ruth 8) Ruth 9) Kings (1&2) 9) 1 Kingdoms (= 1 Sam) 9) 1 Samuel 9) 1 Samuel 10) 2 Kingdoms (= 2 Sam) 10) 2 Samuel 10) 2 Samuel 11) 3 Kingdoms (= 1 Kings) 11) 1 Kings 11) 1 Kings Nevi’im / Latter Prophets 12) 4 Kingdoms (= 2 Kings) 12) 2 Kings 12) 2 Kings 10) Isaiah 13) 1 Chronicles 13) 1 Chronicles 13) 1 Chronicles 11) Jeremiah 14) 2 Chronicles 14) 2 Chronicles 14) 2 Chronicles 12) Ezekiel 15) 1 Esdras 13) The Book of the Twelve: 16) 2 Esdras (= Ezra + Nehemiah) 15) Ezra 15) Ezra Hosea, Joel, 17) Esther (longer version) 16) Nehemiah 16) Nehemiah Amos, Obadiah, 18) JUDITH 17) TOBIT Jonah, Micah, 19) TOBIT 18) JUDITH Nahum, Habakkuk, 19) Esther (longer version) 17) Esther (shorter version) Zephaniah, Haggai, 20) 1 MACCABEES 20) -

A Psychoanalytic Interpretation of Lorenzo Sabatini's Giuditta Con La Testa Di Oloferne

University of Texas at Tyler Scholar Works at UT Tyler Art and Art History Theses Art and Art History Fall 12-13-2019 The Fearsome Femme: A Psychoanalytic Interpretation of Lorenzo Sabatini's Giuditta con la testa di Oloferne Brant J. Bellatti University of Texas at Tyler Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uttyler.edu/art_grad Part of the Ancient, Medieval, Renaissance and Baroque Art and Architecture Commons, and the Art and Design Commons Recommended Citation Bellatti, Brant J., "The Fearsome Femme: A Psychoanalytic Interpretation of Lorenzo Sabatini's Giuditta con la testa di Oloferne" (2019). Art and Art History Theses. Paper 3. http://hdl.handle.net/10950/2322 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Art and Art History at Scholar Works at UT Tyler. It has been accepted for inclusion in Art and Art History Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholar Works at UT Tyler. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE FEARSOME FEMME: A PSYCHOANALYTIC INTERPRETATION OF LORENZO SABATINI’S GIUDITTA CON LA TESTA DI OLOFERNE by Brant Bellatti A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Art and Art History Elizabeth A. Lisot-Nelson, Ph.D., Committee Chair College of Arts and Sciences The University of Texas at Tyler November 2019 The University of Texas at Tyler Tyler, Texas This is to certify that the Master’s Thesis of BRANT BELLATTI has been approved for the thesis 18 November 2019 Master of Art degree Approvals: __________________________________ Thesis Chair: Elizabeth A. -

The New Testament Canon in the Lutheran Dogmaticians I

The New Testament Canon In The Lutheran Dogmaticians I. A. 0. L’REUS Uli lxqose is to study the teachings of the Lutheran dogma- 0 ticians in the period of orthodoxy in regard to the Canon of the New Testament, specifically their criteria of canonicity. In or&r to SW the tlogmaticians in their historical setting, we shall first seek an overview of the teachings of Renaissance Catholicism, Luther, and Reformed regarding Canon. Second, we shall consider the cari). dogmaticians of Lutheranism who wrote on the back- groui~cl of the Council of Trent. Third, we shall consider the later Lutheran dogmaticians to set the direction in which the subject finally developed. 1. THE BACKGROUND In 397 A. D. the Third Council of Carthage bore witness to the Canon of the New Testament as we know it today. Augustine was present, and acquiesced, although tve know from his writings (e.g. IJc l)octrina Christiana II. 12) that he made a distinction between antilegomena and homolegoumena. The Council was held during the period of Jerome’s greatest activity, and his use and gen- cral rccollllnendatioll of the 27 New Testament books insured their acceptance and recognition throughout the Western Church from this time on. Jerome, however, also, it must be noted, had ‘his doubts about the antiiegomena. With the exception of the inclu- sion and later exclusion of the spurious Epistle to the Laodiceans in certain Wcstcrn Bibles during the Middle Ages, the matter of New Testament Canon was settled from Carthage III until the Renais- sance. The Renaissance began within Roman Catholicism. -

Baruch /Letter of Jeremiah – Summary from Session One

Living in Times of Uncertainty – Word from a Prophet and His Scribe: Baruch /Letter of Jeremiah – Summary from Session One Editor’s Note: The final session of the four-part study of the book of Baruch and the Letter of Jeremiah was held on Monday, February 24, 2020. This is a summary of the first of those sessions. Summaries of the other three sessions will follow in the coming weeks. At the time we concluded this series in late February, we were certainly aware that the COVID- 19 virus was having a serious impact in China and other parts of the world, but its influence on daily life in the United States had not yet struck home. In the past few days and weeks our lives have altered radically as fear, uncertainty and constantly changing norms have come to dominate our waking moments. The book of Baruch and the Letter of Jeremiah were written about even more unsettling times – a time of exile into Babylon (597 – 586 b.c.e.), loss of home and life, and even a sense of estrangement from God as the Temple in Jerusalem was destroyed along with much of the city. The original readers of these works, however, were not those exiles of the early sixth century, but lived in yet another, later time of loss, fear, and great uncertainty. Perhaps today, in our own current crisis, we can better identify with those people for whom these works were written. – Charlie Walden (March 23, 2020) PREFACE Baruch (pronounced B-uh-roo-k(ah); [roo rhymes with food]) was a scribe of the prophet Jeremiah, who prophesied before and during the exile of the Jews to Babylon.