The New Testament Canon in the Lutheran Dogmaticians I

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Luther's Bible the Ehv 500Th Anniversary Lutheran

LUTHER’S BIBLE & THE EHV O N T H E 500TH ANNIVERSARY O F T H E LUTHERAN REFORMATION Alle Schrift von Gott eingegeben October 31, 2017 Introductory Thoughts on the 500th Anniversary of the Lutheran Reformation We are celebrating 500 years of the Lutheran Reformation, and there is much to celebrate. We praise God that we are saved by grace alone through faith alone in Jesus Christ alone. We learn this from Scripture alone. To God alone be all the glory and praise! Most say that the Reformation started on October 31, 1517. On that day, Dr. Martin Luther sent a letter to the Archbishop of Mainz about indulgences. Here are a few excerpts from that letter: Under your most distinguished name, papal indulgences are offered all across the land for the construction of St. Peter’s…. I bewail the gross misunderstanding…. Evidently the poor souls believe that when they have bought indulgence letters they are then assured of their salvation. After all, the indulgences contribute absolutely nothing to the salvation and holiness of souls.1 After that, Luther also posted his Ninety-five Theses on the Castle Church door. These Latin statements were intended for public debate by university professors and theologians. Contrary to Luther’s expectations, his Ninety-five Theses were translated, published, and read by many people throughout Germany and in many other places. This was the spark that started the Reformation. Yet Luther was still learning from Scripture. In 1517, Luther still thought he was on the side of the Pope. By October of 1520, Luther had become clearer about many things. -

Table of Contents

Table of Contents Page Title & Author 1 Preface Dr. Sam Nafzger, The Lutheran Church - Missouri Synod 2 Introduction Rev. Dr. William Mundt, Lutheran Church-Canada 5 The Apostles’ Creed Rev. Daniel Inyang, The Lutheran Church of Nigeria 8 The Nicene Creed Rev. Dr. Masao Shimodate, Japan Lutheran Church 11 The Athanasian Creed Rev. Reg Quirk, The Evangelical Lutheran Church of England 14 The Augsburg Confession of 1530 Rev. Dr. Jose Pfaffenzeller, Evangelical Lutheran Church of Argentina 17 Apology of the Augsburg Confession 1531 Dr. Paulo Buss, Evangelical Lutheran Church of Brazil 20 The Smalcald Articles 1537 Rev. Dr. Dieter Reinstorf, Free Evangelical Lutheran Synod in South Africa 23 Treatise on the Power and Primacy of the Pope Rev. Dr. Jin-Seop Eom, Lutheran Church in Korea 26 The Small Catechism Rev. Dr. Wilbert Kreiss, Evangelical Lutheran Church Synod of France & Belgium 29 The Large Catechism Dr. Werner Klän, Independent Evangelical - Lutheran Church 32 The Formula of Concord Dr. Andrew Pfeiffer, Lutheran Church of Australia 35 A Source of Harmony – Peace and a Sword Dr. Jeffrey Oschwald, The Lutheran Church - Missouri Synod International Lutheran Council © 2005 Copyright Preface By Dr. Samuel H. Nafzger Commission on Theology and Church Relations Serves in The Lutheran Church - Missouri Synod 2005 marks the 475th anniversary of the presentation of the Augsburg Confession before Holy Roman Emperor Charles V on June 25, 1530 and the 425th anniversary of the publication of the Book of Concord on June 25, 1575. To commemorate these important occasions, 10 essays prepared by seminary professors and theologians from member churches of the International Lutheran Council have been prepared to present an overview of each of the Book of Concord’s component parts. -

The Apocrypha1!Deuterocanonical Books: an Evangelical View

XIV lated widely in the Hellenistic church, many have argued that (a) the Septuagint represents an Alexandrian (as opposed to a Palestinian) canon, and that (b) the early church, using a Greek Bible, there fore clearly bought into this alternative canon. In any case, (c) the Hebrew canon was not "closed" until Jamnia (around 85 C.E.), so the earliest Christians could not have thought in terms of a closed Hebrew The Apocrypha1!Deuterocanonical Books: canon. "It seems therefore that the Protestant position must be judged a failure on historical grounds."2 An Evangelical View But serious objections are raised by traditional Protestants, including evangelicals, against these points. (a) Although the LXX translations were undertaken before Christ, the LXX evidence that has D. A. CARSON come down to us is both late and mixed. An important early manuscript like Codex Vaticanus (4th cent.) includes all the Apocrypha except 1 and 2 Maccabees; Codex Sinaiticus (4th cent.) has Tobit, Judith, Evangelicalism is on many points so diverse a movement that it would be presumptuous to speak of the 1 and 2 Maccabees, Wisdom, and Ecclesiasticus; another, Codex Alexandrinus (5th cent.) boasts all the evangelical view of the Apocrypha. Two axes of evangelical diversity are particularly important for the apocryphal books plus 3 and 4 Maccabees and the Psalms of Solomon. In other words, there is no evi subject at hand. First, while many evangelicals belong to independent and/or congregational churches, dence here for a well-delineated set of additional canonical books. (b) More importantly, as the LXX has many others belong to movements within national or mainline churches. -

Syllabus, Deuterocanonical Books

The Deuterocanonical Books (Tobit, Judith, 1 & 2 Maccabees, Wisdom, Sirach, Baruch, and additions to Daniel & Esther) Caravaggio. Saint Jerome Writing (oil on canvas), c. 1605-1606. Galleria Borghese, Rome. with Dr. Bill Creasy Copyright © 2021 by Logos Educational Corporation. All rights reserved. No part of this course—audio, video, photography, maps, timelines or other media—may be reproduced or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage or retrieval devices without permission in writing or a licensing agreement from the copyright holder. Scripture texts in this work are taken from the New American Bible, revised edition © 2010, 1991, 1986, 1970 Confraternity of Christian Doctrine, Washington, D.C. and are used by permission of the copyright owner. All Rights Reserved. No part of the New American Bible may be reproduced in any form without permission in writing from the copyright owner. 2 The Deuterocanonical Books (Tobit, Judith, 1 & 2 Maccabees, Wisdom, Sirach, Baruch, and additions to Daniel & Esther) Traditional Authors: Various Traditional Dates Written: c. 250-100 B.C. Traditional Periods Covered: c. 250-100 B.C. Introduction The Deuterocanonical books are those books of Scripture written (for the most part) in Greek that are accepted by Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox churches as inspired, but they are not among the 39 books written in Hebrew accepted by Jews, nor are they accepted as Scripture by most Protestant denominations. The deuterocanonical books include: • Tobit • Judith • 1 Maccabees • 2 Maccabees • Wisdom (also called the Wisdom of Solomon) • Sirach (also called Ecclesiasticus) • Baruch, (including the Letter of Jeremiah) • Additions to Daniel o “Prayer of Azariah” and the “Song of the Three Holy Children” (Vulgate Daniel 3: 24- 90) o Suzanna (Daniel 13) o Bel and the Dragon (Daniel 14) • Additions to Esther Eastern Orthodox churches also include: 3 Maccabees, 4 Maccabees, 1 Esdras, Odes (which include the “Prayer of Manasseh”) and Psalm 151. -

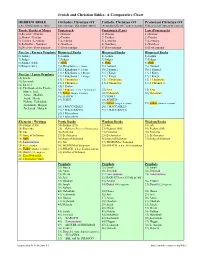

Hebrew and Christian Bibles: a Comparative Chart

Jewish and Christian Bibles: A Comparative Chart HEBREW BIBLE Orthodox Christian OT Catholic Christian OT Protestant Christian OT (a.k.a. TaNaK/Tanakh or Mikra) (based on longer LXX; various editions) (Alexandrian LXX, with 7 deutero-can. bks) (Cath. order, but 7 Apocrypha removed) Torah / Books of Moses Pentateuch Pentateuch (Law) Law (Pentateuch) 1) Bereshit / Genesis 1) Genesis 1) Genesis 1) Genesis 2) Shemot / Exodus 2) Exodus 2) Exodus 2) Exodus 3) VaYikra / Leviticus 3) Leviticus 3) Leviticus 3) Leviticus 4) BaMidbar / Numbers 4) Numbers 4) Numbers 4) Numbers 5) Devarim / Deuteronomy 5) Deuteronomy 5) Deuteronomy 5) Deuteronomy Nevi’im / Former Prophets Historical Books Historical Books Historical Books 6) Joshua 6) Joshua 6) Joshua 6) Joshua 7) Judges 7) Judges 7) Judges 7) Judges 8) Samuel (1&2) 8) Ruth 8) Ruth 8) Ruth 9) Kings (1&2) 9) 1 Kingdoms (= 1 Sam) 9) 1 Samuel 9) 1 Samuel 10) 2 Kingdoms (= 2 Sam) 10) 2 Samuel 10) 2 Samuel 11) 3 Kingdoms (= 1 Kings) 11) 1 Kings 11) 1 Kings Nevi’im / Latter Prophets 12) 4 Kingdoms (= 2 Kings) 12) 2 Kings 12) 2 Kings 10) Isaiah 13) 1 Chronicles 13) 1 Chronicles 13) 1 Chronicles 11) Jeremiah 14) 2 Chronicles 14) 2 Chronicles 14) 2 Chronicles 12) Ezekiel 15) 1 Esdras 13) The Book of the Twelve: 16) 2 Esdras (= Ezra + Nehemiah) 15) Ezra 15) Ezra Hosea, Joel, 17) Esther (longer version) 16) Nehemiah 16) Nehemiah Amos, Obadiah, 18) JUDITH 17) TOBIT Jonah, Micah, 19) TOBIT 18) JUDITH Nahum, Habakkuk, 19) Esther (longer version) 17) Esther (shorter version) Zephaniah, Haggai, 20) 1 MACCABEES 20) -

The Luther Bible of 1534 Pdf Free Download

THE LUTHER BIBLE OF 1534 PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Taschen,Stephan Füssel | 1920 pages | 01 Jun 2016 | Taschen GmbH | 9783836538305 | English | Cologne, Germany The Luther Bible of 1534 PDF Book Gruber 37 Biblia, das ist die gantze Heilige Schrifft Deudsch We are very happy that Rufus Beck, the renowned German actor, will contribute to the recording. The New Testament was released September 21, , and a second edition was produced the same December. Some Catholic sources state and certain historians contend that until the definition of the Council of Trent issued on April 8, , the Roman Catholic Church had not yet dogmatically defined the contents of the biblical canon for Catholics and thus settled the matter. Review : "A splendid, two-volume colour facsimile, with an excellent scholarly commentary. Views Read Edit View history. Evangelicals tend not to accept the Septuagint as the inspired Hebrew Bible, though many of them recognize its wide use by Greek-speaking Jews in the first century. Retrieved Condition: Nuevo. James was dealing with errorists who said that if they had faith they didn't need to show love by a life of faith James Seller Inventory n. How can the world become more socially just? On the left, the Law is depicted as it appears in the Old Testament; for example, Adam and Eve are shown eating the fruit of the tree of life after being tempted by the serpent. All Saints' Church presents itself - like many other Luther memorial sites - freshly renovated in time for the jubilee. Digital Culture. In the special anniversary edition, there are additional pages describing Luther's life as a reformer and Bible translator, in addition to some of the preambles of the first editions of Luther's Bible. -

The Apocryphal/Deuterocanonical Books of the Old Testament

Adult Catechism April 11, 2016 The Apocryphal/Deuterocanonical Books of the Old Testament Part 1: Scripture Readings: Sirach 7: 1-3 : After If you do no wrong, no wrong will ever come to you. Do not plow the ground to plant seeds of injustice; you may reap a bigger harvest than you expect. Baruch 1:15-21: This is the confession you should make: The Lord our God is righteous, but we are still covered with shame. All of us—the people of Judah, the people of Jerusalem, our kings, our rulers, our priests, our prophets, and our ancestors have been put to shame, because we have sinned against the Lord our God and have disobeyed him. We did not listen to him or live according to his commandments. From the day the Lord brought our ancestors out of Egypt until the present day, we have continued to be unfaithful to him, and we have not hesitated to disobey him. Long ago, when the Lord led our ancestors out of Egypt, so that he could give us a rich and fertile land, he pronounced curses against us through his servant Moses. And today we are suffering because of those curses. We refused to obey the word of the Lord our God which he spoke to us through the prophets. Instead, we all did as we pleased and went on our own evil way. We turned to other gods and did things the Lord hates. Part 2: What are the Apocryphal/Deuterocanonical Books of the Old Testament?: The word “Apocrypha” means “hidden” and can refer to books meant only for the inner circle, or books not good enough to be read, or simply books outside of the canon. -

Historiography Early Church History

HISTORIOGRAPHY AND EARLY CHURCH HISTORY TABLE OF CONTENTS Historiography Or Preliminary Issues......................................................... 4 Texts ..................................................................................................................... 4 Introduction ................................................................................................. 5 Definition.............................................................................................................. 5 Necessity............................................................................................................... 5 What Is Church History?............................................................................. 6 What Is The Biblical Philosophy Of History? ............................................ 7 The Doctrine Of God............................................................................................ 7 The Doctrine Of Creation..................................................................................... 8 The Doctrine Of Predestination............................................................................ 8 Why Study Church History? ....................................................................... 9 The Faithfulness Of God .................................................................................... 10 Truth And Experience ........................................................................................ 10 Truth And Tradition .......................................................................................... -

Council of Jerusalem from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Council of Jerusalem From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia The Council of Jerusalem (or Apostolic Conference) is a name applied by historians to an Early Christian council that was held in Jerusalem and dated to around the year 50. It is considered by Catholics and Orthodox to be a prototype and forerunner of the later Ecumenical Councils. The council decided that Gentile converts to Christianity were not obligated to keep most of the Mosaic law, including the rules concerning circumcision of males, however, the Council did retain the prohibitions against eating blood, or eating meat containing blood, or meat of animals not properly slain, and against fornication and idolatry. Descriptions of the council are found in Acts of the Apostles chapter 15 (in two different forms, the Alexandrian and Western versions) and also possibly in Paul's letter to the Galatians chapter 2.[1] Some scholars dispute that Galatians 2 is about the Council of Jerusalem (notably because Galatians 2 describes a private meeting) while other scholars dispute the historical reliability of the Acts of the Apostles. Paul was likely an eyewitness and a major person in attendance whereas the writer of Luke-Acts probably[citation needed] wrote second-hand about James the Just, whose judgment was the meeting he described in Acts 15. adopted in the Apostolic Decree of Acts 15:19-29 (http://bibref.hebtools.com/? book=%20Acts&verse=15:19- Contents 29&src=!) , c. 50 AD: "...we should write to them [Gentiles] to abstain 1 Historical background only from things polluted by idols -

The Role of Metatexts in the Translations of Sacred Texts: the Case of the Book of Aristeas and the Septuagint

THE ROLE OF METATEXTS IN THE TRANSLATIONS OF SACRED TEXTS: THE CASE OF THE BOOK OF ARISTEAS AND THE SEPTUAGINT Jacobus A. Naudé1 University of the Free State 1. Introduction Translations of sacred texts through the centuries were accompanied by metatexts narrating the origin and nature of the specific translation (for example, the Book of Aristeas2 and the Septuagint [LXX]; Dolmetschen and the Luther Bible Translation; the metatexts in the Dutch Authoritative Bible Translation [Statevertaling], etc). However, in the twentieth century Bible translations accompanied by metatexts were very rare. But in the twenty-first century Bible translations have again made use of metatexts (for example, the successful Nieuwe Bijbelvertaling, Das Neue Testament, The Schocken Bible, Die Bybel vir Dowes, etc.). Metatexts will also play a major role in the next Afrikaans Bible translation. The aim of this article is to investigate previous scholarship and to suggest a new avenue for explaining the role of the Book of Aristeas as metatext in the translation of a sacred text, namely the LXX. This exploration will be continued in subsequent articles in the future. The framework for this study is Descriptive Translation Studies, which adopts a descriptive approach towards translation in accounting for the role of metatexts in Bible and religious translations. The descriptive approach originated in the 1970s with Even-Zohar’s polysystem theory and created the impetus for the study of translation to move in the direction of an investigation of the position of translated literature as a whole vis-á-vis the historical and literary systems of the target culture. -

The Book of Revelation (Apocalypse)

KURUVACHIRA JOSE EOBIB-210 1 Student Name: KURUVACHIRA JOSE Student Country: ITALY Course Code or Name: EOBIB-210 This paper uses UK standards for spelling and punctuation THE BOOK OF REVELATION (APOCALYPSE) 1) Introduction Revelation1 or Apocalypse2 is a unique, complex and remarkable biblical text full of heavenly mysteries. Revelation is a long epistle addressed to seven Christian communities of the Roman province of Asia Minor, modern Turkey, wherein the author recounts what he has seen, heard and understood in the course of his prophetic ecstasies. Some commentators, such as Margaret Barker, suggest that the visions are those of Christ himself (1:1), which He in turn passed on to John.3 It is the only book in the New Testament canon that shares the literary genre of apocalyptic literature4, though there are short apocalyptic passages in various places in the 1 Revelation is the English translation of the Greek word apokalypsis (‘unveiling’ or ‘uncovering’ in order to disclose a hidden truth) and the Latin revelatio. According to Adela Yarbro Collins, it is likely that the author himself did not provide a title for the book. The title Apocalypse came into usage from the first word of the book in Greek apokalypsis Iesou Christon meaning “A revelation of Jesus Christ”. Cf. Adela Yarbro Collins, “Revelation, Book of”, pp. 694-695. 2 In Codex Sinaiticus (4th century), Codex Alexandrinus (5th century) and Codex Ephraemi (5th century) the title of the book is “Revelation of John”. Other manuscripts contain such titles as, “Revelation of John, the one who speaks about God”, “Revelation of Saint John, the one who speaks about God”, “Revelation of John, the one who speaks about God, [the] evangelist” and “The Revelation of the Apostle John, the Evangelist”. -

Volume 79:3–4 July/October 2015

Concordia Theological Quarterly Volume 79:3–4 July/October 2015 Table of Contents The Lutheran Hymnal after Seventy-Five Years: Its Role in the Shaping of Lutheran Service Book Paul J. Grime ..................................................................................... 195 Ascending to God: The Cosmology of Worship in the Old Testament Jeffrey H. Pulse ................................................................................. 221 Matthew as the Foundation for the New Testament Canon David P. Scaer ................................................................................... 233 Luke’s Canonical Criterion Arthur A. Just Jr. ............................................................................... 245 The Role of the Book of Acts in the Recognition of the New Testament Canon Peter J. Scaer ...................................................................................... 261 The Relevance of the Homologoumena and Antilegomena Distinction for the New Testament Canon Today: Revelation as a Test Case Charles A. Gieschen ......................................................................... 279 Taking War Captive: A Recommendation of Daniel Bell’s Just War as Christian Discipleship Joel P. Meyer ...................................................................................... 301 Marriage, Divorce, and Remarriage: The Triumph of Culture? Gifford A. Grobien ............................................................................ 315 Pastoral Care and Sex Harold L. Senkbeil .............................................................................