Indian Outbreaks

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

West Side News, February 22, 1890

Wright State University CORE Scholar West Side News Wright Brothers Newspapers 2-22-1890 West Side News, February 22, 1890 Orville Wright Follow this and additional works at: https://corescholar.libraries.wright.edu/west_side_news Part of the History Commons, and the Mass Communication Commons Repository Citation Wright , O. (1890). West Side News, February 22, 1890. This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Wright Brothers Newspapers at CORE Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in West Side News by an authorized administrator of CORE Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. IDE EWS. Vol. 1. DAYTON, OHIO, SATURDAY, FEBRUARY 22, 1890. No. 48. onel turned red and white by A Capital Answer. West Side f'lews, turns, bit his lip , and bobbed JOHN A. SCHENK, about on the seat, and as we held Teacher (to dull boy of the 108 South Jefferson St., Prices that None PUBI~ISHED \VEETH~ Y. our breaths he lrnrst out with: class)-Which New England State Can ~frttch '"Gentlemen, h e~ ut s trings be has two capitals? Qua1itif'S tJ1at Non c C!>~:YJ~l:.'E W~JG}f?f-, blow eel ! The OJH' l'.V, thieving, ( ' an l~ ctuiil! Boy-New Hamp hire. I>h·c•c•t l)('alc•1· in nll EDITOR AND PUBLISHER. Ion ling, lying crow cl hn ve 0 ·one 'l1eacher-Indeed? Name -them. Goods J Helli and heaped a de<tdl.v inonlt upon SUBSCRIPTION ltATE~. lfJ-1 'E <::> 1:. t:> ~ E 1:. J}l B 1:. 'E m.e. -

Renfrew, Lemkay Research

APPENDIX Booth ’s railway goes through Algonquin Park, 252 miles from Ottawa to Deport Harbour THE PLAYERS The Ottawa, Arnprior and Parry Sound Railway is frequently called “Booth’s Railway,” and much well-deserved credit is due to the great entrepreneur and visionary who had the foresight and talent to make it happen. John Rudolphus Booth , (1827 – 1925) rapidly evolved from a carpenter in the Eastern Townships of Quebec to become a multi-millionaire businessman in Ottawa. Following are the relatively unknown engineers, surveyors and contractors whose dedication and toil made the realization of this tremendous project possible. George Alonzo Mountain, civil engineer, born in Quebec City in 1860 moved to Ottawa in 1883. He joined the Canada Atlantic Railway in 1881 as it was being constructed and became the chief engineer of the CAR in 1887. He successfully located and built the Ottawa, Arnprior and Parry Sound Railway between 1891 and 1896. His assignment was to survey a road through virgin bush from Ottawa to Parry Sound in the shortest distance possible and with a minimum of hills and valleys. Later, he was also the engineer in charge of the construction of the bridge crossing the St. Lawrence River at Coteau, Quebec. He became a Railway Commissioner in 1904. William Shillito Cranston, ( 1863 – 1902) was born in Arnprior, a son of Dr. J. Cranston. William was a civil engineer, graduate of McGill University, and practised throughout Canada. He was the surveyor for Chief Engineer George A. Mountain, on the determination of the site for OA & PSRR. He later worked for the CPR in the construction of the Crow’s Nest Pass, and, at the time of his death, was the City Engineer for Ottawa. -

White by Law---Haney Lopez (Abridged Version)

White by Law The Legal Construction of Race Revised and Updated 10th Anniversary Edition Ian Haney Lόpez NEW YORK UNIVERSITY PRESS New York and London (2006) 1│White Lines In its first words on the subject of citizenship, Congress in 1790 restricted naturalization to “white persons.” Though the requirements for naturalization changed frequently thereafter, this racial prerequisite to citizenship endured for over a century and a half, remaining in force until 1952. From the earliest years of this country until just a generation ago, being a “white person” was a condition for acquiring citizenship. Whether one was “white” however, was often no easy question. As immigration reached record highs at the turn of this century, countless people found themselves arguing their racial identity in order to naturalize. From 1907, when the federal government began collecting data on naturalization, until 1920, over one million people gained citizenship under the racially restrictive naturalization laws. Many more sought to naturalize and were rejected. Naturalization rarely involved formal court proceedings and therefore usually generated few if any written records beyond the simple decision. However, a number of cases construing the “white person” prerequisite reached the highest state and federal judicial circles, and two were argued before the U.S. Supreme Court in the early 1920s. These cases produced illuminating published decisions that document the efforts of would-be citizens from around the world to establish their Whiteness at law. Applicants from Hawaii, China, Japan, Burma, and the Philippines, as well as all mixed- race applicants, failed in their arguments. Conversely, courts ruled that applicants from Mexico and Armenia were “white,” but vacillated over the Whiteness of petitioners from Syria, India, and Arabia. -

Was Gen. Henry Sibley's Son Hanged in Mankato?

The Filicide Enigma: Was Gen. Henry Sibley’s Son Ha nged in Ma nkato? By Walt Bachman Introduction For the first 20 years of Henry Milord’s life, he and Henry Sibley both lived in the small village of Mendota, Minnesota, where, especially during Milord’s childhood, they enjoyed a close relationship. But when the paths of Sibley and Milord crossed in dramatic fashion in the fall of 1862, the two men had lived apart for years. During that period of separation, in 1858 Sibley ascended to the peak of his power and acclaim as Minnesota’s first governor, presiding over the affairs of the booming new state from his historic stone house in Mendota. As recounted in Rhoda Gilman’s excellent 2004 biography, Henry Hastings Sibley: Divided Heart, Sibley had occupied key positions of leadership since his arrival in Minnesota in 1834, managing the regional fur trade and representing Minnesota Territory in Congress before his term as governor. He was the most important figure in 19th century Minnesota history. As Sibley was governing the new state, Milord, favoring his Dakota heritage on his mother’s side, opted to live on the new Dakota reservation along the upper Minnesota River and was, according to his mother, “roaming with the Sioux.” Financially, Sibley was well-established from his years in the fur trade, and especially from his receipt of substantial sums (at the Dakotas’ expense) as proceeds from 1851 treaties. 1 Milord proba bly quickly spe nt all of the far more modest benefit from an earlier treaty to which he, as a mixed-blood Dakota, was entitled. -

And the Hamitic Hypothesis

religions Article Ancient Egyptians in Black and White: ‘Exodus: Gods and Kings’ and the Hamitic Hypothesis Justin Michael Reed Department of Biblical Studies, Louisville Presbyterian Theological Seminary, Louisville, KY 40205, USA; [email protected] Abstract: In this essay, I consider how the racial politics of Ridley Scott’s whitewashing of ancient Egypt in Exodus: Gods and Kings intersects with the Hamitic Hypothesis, a racial theory that asserts Black people’s inherent inferiority to other races and that civilization is the unique possession of the White race. First, I outline the historical development of the Hamitic Hypothesis. Then, I highlight instances in which some of the most respected White intellectuals from the late-seventeenth through the mid-twentieth century deploy the hypothesis in assertions that the ancient Egyptians were a race of dark-skinned Caucasians. By focusing on this detail, I demonstrate that prominent White scholars’ arguments in favor of their racial kinship with ancient Egyptians were frequently burdened with the insecure admission that these ancient Egyptian Caucasians sometimes resembled Negroes in certain respects—most frequently noted being skin color. In the concluding section of this essay, I use Scott’s film to point out that the success of the Hamitic Hypothesis in its racial discourse has transformed a racial perception of the ancient Egyptian from a dark-skinned Caucasian into a White person with appearance akin to Northern European White people. Keywords: Ham; Hamite; Egyptian; Caucasian; race; Genesis 9; Ridley Scott; Charles Copher; Samuel George Morton; James Henry Breasted Citation: Reed, Justin Michael. 2021. Ancient Egyptians in Black and White: ‘Exodus: Gods and Kings’ and Religions the Hamitic Hypothesis. -

Little Crow Historic Canoe Route

Taoyateduta Minnesota River HISTORIC water trail BOY SCOUTS OF AMERICA Twin Valley Council U.S.-Dakota War of 1862 AUGUST 17, 1862 The TA-OYA-TE DUTA Fish and Wildlife Minnesota River Historic Water Four Dakota men kill five settlers The Minnesota River Basin is a Trail, is an 88 mile water route at Acton in Meeker County birding paradise. The Minnesota stretching from just south of AUGUST 18 River is a haven for bird life and Granite Falls to New Ulm, Minne- several species of waterfowl and War begins with attack on the sota. The river route is named af- riparian birds use the river corri- Lower Sioux Agency and other set- ter Taoyateduta (Little Crow), the dor for nesting, breeding, and rest- tlements; ambush and battle at most prominent Dakota figure in ing during migration. More than the U.S.-Dakota War of 1862. Redwood Ferry. Traders stores 320 species have been recorded in near Upper Sioux Agency attacked the Minnesota River Valley. - The Minnesota River - AUGUST 19 Beneath the often grayish and First attack on New Ulm leading to The name Minnesota is a Da- cloudy waters of the Minnesota its evacuation; Sibley appointed kota word translated variously as River, swim a diverse fish popula- "sky-tinted water” or “cloudy-sky tion. The number of fish species commander of U.S. troops water". The river is gentle and and abundance has seen a signifi- AUGUST 20 placid for most of its course and cant rebound over the last several First Fort Ridgely attack. one will encounter only a few mi- years. -

Comprehensive Historic Preservation Plan Was Written in 2009

NORTH DAKOTA STATE HISTORIC PRESERVATION OFFICE ARCHAEOLOGY AND HISTORIC PRESERVATION DIVISION STATE HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF NORTH DAKOTA 612 EAST BOULEVARD AVENUE BISMARCK, NORTH DAKOTA 58505-0830 PRESERVATION IN NORTH DAKOTA, 2016-2021: A Statewide Comprehensive Plan PRESERVATION IN NORTH DAKOTA, 2016-2021: Telephone: (701) 328-2672 FAX: (701) 328-3710 http://history.nd.gov HISTORIC December 2015 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS: The preparation of this plan revision was a group effort. Research, discussion, writing and reviews were performed primarily by the staff of the State Historic Preservation Office, sitting as an ad hoc planning committee and by other individuals from the staff of the State Historical Society of North Dakota, each bringing his or her own perspective, expertise, experience and philosophical viewpoints, to help formulate a comprehensive yet balanced preservation concept. Preservation constituents and respondents from the general public gave time and generously contributed ideas, evaluations, suggestions, concerns, and assessments. To each and all of these sincere gratitude is offered, as it is to previous staff and public participants whose contributions to earlier planning studies and efforts were of great value to the development of this plan. This document may be provided in other communication formats. If special format copies are desired, please contact: The Division of Archaeology and Historic Preservation State Historical Society of North Dakota 612 East Boulevard Avenue Bismarck, North Dakota 58505 Telephone: (701) 328-2672 Fax: (701) 328-3710 http://history.nd.gov The State Historical Society of North Dakota receives federal funds from the U. S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, to assist with costs of administering the Historic Preservation program in this state. -

Shallowater Darla S

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1994 Shallowater Darla S. Bielfeldt Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the Composition Commons, Fiction Commons, and the Poetry Commons Recommended Citation Bielfeldt, Darla S., "Shallowater" (1994). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 172. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/172 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Shallowater by Darla Stolz Bielfeldt A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS Department: English Major: English Approved: Signature redacted for privacy / L- Signature redacted for privacy For the Major Department Signature redacted for privacy For the Graduate College Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 1994 11 TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS iv GENERAL INTRODUCTION An Explantaion of the Thesis Organization 1 PART 1. SHALLOWATER 2 HOME 3 FIRST BORN 5 GREAT-GRANDMA 6 HOMECOMING 7 GIRLS 10 TURTLES 12 NIGHT LINES 13 LEARNING BLACK AND WHITE 15 FLESH WOUND 18 REUNION 19 HUMAN SHAPES 21 ROAD TRIP 22 THE KIDD KIDS 23 THE LUCKY "B" 25 BETTIE 28 IMPARTED KNOWLEDGE 33 HOC EST CORPUS MEUM 35 HOME AGAIN 37 lV ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Thank you to Prof. Mary Swander whose own poetic style and advice encouraged me to push these writings into longer pieces. -

Race & Ethnicity in Independent Films

Race & Ethnicity in Independent Films: Prevalence of Underrepresented Directors and the Barriers They Face Katherine M. Pieper, Ph.D., Marc Choueiti, & Stacy L. Smith, Ph.D. Annenberg School for Communication & Journalism University of Southern California (working paper) This project was supported in part or in whole by an award from the Research: Art Works program at the National Endowment for the Arts: Grant# 13-3800-7017. The opinions expressed in this paper are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the views of the Office of Research & Analysis or the National Endowment for the Arts. The NEA does not guarantee the accuracy or completeness of the information included in this report and is not responsible for any consequence of its use. 1 Race & Ethnicity in Independent Films: Prevalence of Underrepresented Directors and the Barriers They Face Katherine M. Pieper, Ph.D., Marc Choueiti, & Stacy L. Smith, Ph.D. Annenberg School for Communication & Journalism University of Southern California 3502 Watt Way, Suite 222-223 Los Angeles, CA 90089 @MDSCInitiative Executive Summary The purpose of this study was to assess the prevalence and experiences of directors from underrepresented racial/ethnic groups in film. To this end, the research involved three prongs. First, we examined race/ethnicity of all directors associated with U.S. dramatic and documentary films selected and screened at Sundance Film Festival (SFF) between 2002 and 2013. Using a modified version of U.S. Census categories, a total of 1,068 directors across more than 900 films were categorized into one or more racial/ethnic groups. Second, we assessed how diversity behind the camera was related to on screen diversity. -

Dakota Conflict of 1862

A Guide to the Microfilm Edition of DAKOTA CONFLICT OF 1862 MANUSCRIPT COLLECTIONS DAKOTA CONFLICT OF 1862 MANUSCRIPT COLLECTIONS Microfilmed by the Minnesota Historical Society Library and Archives, M582, Dakota Conflict of 1862, Manuscript Collections, 1862-1962 Project Coordinator Martin Schipper Guide compiled by Dale Reynolds and Robert E. Lester Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Dakota Conflict of 1862 [microform]: manuscript collections/project coordinator, Martin Schipper. microfilm reels. Summary: Reproduces 144 small collections of letters, reminiscences, reports, diaries, and related materials dealing with Minnesota's Dakota Conflict and related events of 1862-1865. "Microfilmed by the Minnesota Historial Society Library and Archives, M582, Dakota Conflict of 1862, Manuscript Collections, 1862-1962." Accompanied by a printed guide compiled by Robert E. Lester, entitled: A guide to the microfilm edition ofDakota conflict of 1862. ISBN 1-55655-855-4 1. Dakota Indians--Wars, 1862-1865--Sources. 2. Indians of North America--Minnesota River Valley(S.D. and Minn.)--Wars, 1862-1865--Sources. I. Schipper, Martin Paul. II. Lester, Robert. III. Minnesota Historical Society. Division of Library and Archives. IV. University Publications of America (Firm) V. Title: Guide to the microfilm edition of Dakota conflict of 1862. E99.D1 973.7--dc21 2002019988 CIP TABLE OF CONTENTS Scope and Content Note v Source Note vii Reel Index Reel 1 "Anderson"-"Grose" 1 Reel 2 "Hagadorn"-"Myers" 7 Reel 3 "Nairn"-"Wood" 15 Reel 4 "Workman"-"Wounded Man" 23 Subj ect Index 25 SCOPE AND CONTENT NOTE In 1862, Minnesota was still a young state, part of a frontier inhabited by more than one million Indians. -

Wisconsin and Iowa Troops Fight Boredom, Not Indians, in Minnesota

NEIGHBORS "TO THE RESCUE" Edward Noyes FOR A SHORT TIME in the fldl of 1862, two regiments bank of the Minnesota River a short distance from neighboring states were dispatched to Minnesota to downstream from its junction with the Redwood. In the help quell the Sioux Uprising, or Dakota War. The units next five days, the Indians twice attacked Fort Ridgely involved were the Twenty-fifth \\'isconsin and the on the north bank of the Minnesota and twice lashed out Twenty-seventh Iowa Volunteer Infantry regiments. The at the German town of New Ulm on the south. When all Wisconsin soldiers served in Minnesota just short of of these attacks were repulsed, the Sioux were unable to three months and the lowans for nearly a month. Militar- condnue down the Minnesota Valley toward St. Paul and ilv', the W-'isconsin men played a role directly associated Minneapolis. In spite of this and their lack of a planned with the Dakota War bv' contributing to the stabilization campaign, the Indians possessed the initiative. By of the frontier. The lowans' main service was to assist exploiting it, they took a heavy toll of white lives, did with an annuitv payment to the restless, but for the most much damage to the property of settlers, and caused the part peaceful, Chippewa (Ojibway) Indians.' wholesale desertion of numerous communities and coun It may be that, because the out-of-state troops were ties.^ in Minnesota only briefly — indeed, some of them won Back in St. Paul, energetic Governor Alexander dered why they were there at all — their campaigning Ramsey met the crisis quickly. -

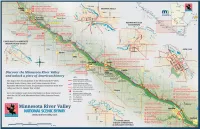

Central-Section-Byway-Tear-Map.Pdf

1 Granite Falls Footbridge 9 Sacred Heart Area Museum 17 Renville County Historical Museum 25 Wanda Gág House This pedestrian suspension bridge was built in 1935 by the A stucco building with a dome-style bell tower where Take a trip back into history by touring the six building The childhood home turned museum of Wanda Hazel Gag, Minneapolis Bridge Company with design and materials people once congregated for church services. Now, home complex. Rotating exhibits, a research library, a author of classic children’s books. from the Roebling & Sons Company (Brooklyn Bridge). to collections of the Sacred Heart Area Historical Society. schoolhouse, and more. 507-359-2632 | 226 N Washington Street, New Ulm 320-321-3202 | 676 Prentice Street, Granite Falls 320-765-8868 | 300 5th Avenue, Sacred Heart 507-697-6147 | 441 N Park Drive, Morton www.wandagaghouse.org www.granitefallschamber.com www.facebook.com/sacredheartmuseum/ www.renvillecountyhistory.com 26 Glockenspiel 2 Andrew J. Volstead House Museum 10 Joseph R. Brown State Wayside Rest 18 Morton Monuments A unique 45-foot, free-standing clock tower with animated A National Historic Landmark, Congressman Volstead was View displays of the granite ruins of Brown’s home which The first obelisk stands in memory of the soldiers figures that depict the city’s history. the co-author of the Capper Volstead Cooperatives Act and was destroyed during the U.S.-Dakota War of 1862. Brown who fought the Battle of Birch Coulee. The second 888-463-9856 | 327 N Minnesota Street, New Ulm author of the Prohibition Enforcement Act or Volstead Act.