Improving Newborn Care in South Africa

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Critical Appraisal of South Africa's Market-Based Land Reform Policy

A critical appraisal of South Africa’s market-based land reform policy: The case of the Land Redistribution for Agricultural Development SCHOOLof (LRAD) programme in Limpopo GOVERNMENT UNIVERSITY OF THE WESTERN CAPE Marc Wegerif Research report no. 19 Research report no. 19 A critical appraisal of South Africa’s market- based land reform policy: The case of the Land Redistribution for Agricultural Development (LRAD) programme in Limpopo Marc Wegerif Programme for Land and Agrarian Studies December 2004 Hanging on a wire: A historical and socio-economic study of Paulshoek village in the communal area of Leliefontein, Namaqualand A critical appraisal of South Africa’s market-based land reform policy: The case of the Land Redistribution for Agricultural Development ( LRAD) programme in Limpopo Marc Wegerif Published by the Programme for Land and Agrarian Studies, School of Government, University of the Western Cape, Private Bag X17, Bellville 7535, Cape Town, South Africa. Tel: +27 21 959 3733. Fax: +27 21 959 3732. [email protected]. www.uwc.ac.za/plaas Programme for Land and Agrarian Studies Research report no. 19 ISBN 1-86808-596-1 December 2004 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without prior permission from the publisher or the author. Copy editor: Stephen Heyns Cover photograph: Richard van Ryneveld Layout: Designs for Development Maps: Anne Westoby (Figure 1) and John Hall (Figure 2) Typeset in Times Printing: Hansa Reproprint Contents List of figures, tables -

1 CHAPTER 1 GENERAL INTRODUCTION 1.1 Introduction

1 CHAPTER 1 GENERAL INTRODUCTION 1.1 Introduction People and things are given names for identification purposes. A name is a title given to a person or a thing. A name is defined by Sebashe (2003:12) as a word or words by which a person, animal, place or a thing is spoken of or referred to. In other words, a name distinguishes a particular thing from others. Names have political, social, economic and religious significance. As far as this study is concerned, the emphasis would be on the political significance of a name. The Black South Africans suffered a significant harm during the apartheid regime. The Europeans dominated in everything which resulted in Blacks losing their identity, culture, values, heritage an tradition. The European domination interfered with the naming patterns of the indigenous people of South Africa. Names of places were virtually Eurocentric. This is evident in town names, for example, Johannesburg, Pretoria, Pietersburg and Potgietersrus. Tables turned when a democratic government was elected in 1994. The affected people started to realize the negative impact of apartheid on numerous things, places names inclusive. The new government started to implement political changes. Some place names are changed to strike a balance between races, new places are named according to what the people want. Place naming starts to shift a distance away from Eurocentric to African names. Towns, streets, sporting facilities, names of settlements, businesses and 2 educational institutions are the most places affected by name changes and new naming patterns. 1.2 Background to the problem The problem of place naming in Africa in general and South Africa in particular started during the colonial period when many European countries scrambled for Africa in the 17th century. -

In the Subject PRATICAL THEOLOGY Developing More Inclusive Liturgy Praxis for Th

University of Pretoria MASTER OF ART (THEOLOGY) In the subject PRATICAL THEOLOGY Developing more inclusive liturgy praxis for the Evangelical Presbyterian Church in South Africa By Hundzukani Portia Khosa Supervisor: Prof C.J. Wepener August 2014 1 | P a g e Declaration I hereby declare that ‗Developing more inclusive liturgy praxis for the Evangelical Presbyterian Church in South Africa’ is my own work and that all sources that I have used have been indicated and acknowledged by means of complete references. Ms H.P. Khosa ----------------------------- ------------------------------------- Ms HP Khosa Date 2 | P a g e For my father, Hlengani Michael Khosa, who spent most of his life in the SANDF for endless months away from home to provide the best for his beautiful wife, Nkhensani Maria Khosa and his three daughters. 3 | P a g e Acknowledgements I would like to extend my deepest thanks and gratitude to the following people for the help and encouragement they all have given me during this research: 1. To my parents, Mr HM and Mrs NM Khosa, who introduced me to the Presbyterian Church from birth.I, extend to them my deepest gratitude for their love and support and for believing in my ministry when many didn‘t. I am the young woman I am today because of their upbringing. 2. To my two beautiful sisters. Nkateko and Tivoneleni (known as Voni) Khosa who always had more faith in me than I had in myself. 3. Nhlamulo Prince Mashava, who did a great job in helping me to understand the liturgy better during my research, Not only did he help me with understanding the liturgy, he indirectly encouraged me to always want to do better in my studies and in life because of the way he carried pride in my work and ministry. -

Your Time Is NOW. Did the Lockdown Make It Hard for You to Get Your HIV Or Any Other Chronic Illness Treatment?

Your Time is NOW. Did the lockdown make it hard for you to get your HIV or any other chronic illness treatment? We understand that it may have been difficult for you to visit your nearest Clinic to get your treatment. The good news is, your local Clinic is operating fully and is eager to welcome you back. Make 2021 the year of good health by getting back onto your treatment today and live a healthy life. It’s that easy. Your Health is in your hands. Our Clinic staff will not turn you away even if you come without an appointment. Speak to us Today! @staystrongandhealthyza Molemole Facility Contact number Physical Address Botlokwa 079 144 0358/ Ramokgopa road, Matseke village Gateway 083 500 6003 Dwarsriver, 0812 Dendron 015 501 0059/ 181 President street, Mongwadi village next 082 068 9394 to Molemole municipality. Eisleben 015 526 7903/ Stand 26, Ga Gammsa- Next to Itieleng 072 250 8191 Primary Clinic Makgato 015 527 7900/ Makgato village, next to Sokaleholo Primary 083 395 2021 School Matoks 015 527 7947/ Stand no 1015, Sekhwana village- Next to 082 374 4965 Rose and Jack Bakery Mohodi 015 505 9011/ Mohodi ga Manthata Fatima, Next to VP 076 685 5482 Manthata high school Nthabiseng 015 397 7933/ Stand no 822, Nthabiseng village. 084 423 7040 Persie 015 229 2900/ Stand no 135, Kolopo village next to Mossie 084 263 3730 Store Ramokgopa 015 526 2022/ S16 Makwetja section ,Next to FET College 072 217 4831 / 078 6197858/ Polokwane East Facility Contact number Physical address A Mamabolo 079 899 3201 / Monangweng- Next to Mankweng High 015 267 -

A Journey to Limpopo Wetlands

DEPARTMENT OF ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT, ENVIRONMENT AND TOURISM STATE OF WETLANDS IN THE LIMPOPO PROVINCE Directorate: Biodiversity Management C/o Suid & Voortrekker Street, POLOKWANE, 0700, Private Bag X9484, POLOKWANE, 0700 Tel: (015) 293 8300, Fax: (015) 295 4120 Website: http/www.limpopo.gov.za 1. Introduction Ramsar Convention on wetlands conservation and wise use was adopted in Ramsar city, Iran in 1971 as contribution towards achieving sustainable development throughout the world. Ramsar Convention also works hand in hand with other convention such as Convention on biological diversity and other related organizations. As contracting party (country member) of Ramsar convention South Africa had designated about 12 wetlands as Ramsar site or site of international importance. Nysvley Nature Reserve and Makuleke floodplain are the two Ramsar sites in the Limpopo Province. According to Ramsar Convention wetlands are area of marshes, fen, peatland, wet grassland, lakes, estuaries, mangroves and coral reefs, whether natural or artificial, permanent or temporary, with water that is static or flowing, fresh, brackish or salt, including areas of marine water the depth of which at low tide does not exceed six metres. Wetlands have different names following the four dominant languages in the Limpopo province, nhlangasi (in Tsonga), Mohlaka or Monyuka (in Pedi) Maroroma or Matzhava (in Venda) and Vlei (in Afrikaans) Conservation, wise use and management of wetlands requires partnership of relevant government departments (e.g. Agriculture, Water Affairs and Forestry, Environmental Affairs and Tourism), local authorities (Municipalities and traditional), Non-governmental organizations (e.g. Working for Wetland, Mondi wetlands project) and other relevant research institutions. As a results wetland stakeholders in the Limpopo Province network and interact through the Limpopo wetlands Forum which is informally coordinated and chaired by SANBI (Working for Wetland) World Wetlands Day is celebrated every year on 2nd of February throughout South Africa and international community. -

Limpopo Province Elim Hospital

Limpopo Province Elim Hospital - Complex Central/Provincial tertiary Hospital/s: Elim District Hospitals: Community Health Centre Primary Health Care: Regional Hospitals: None Siloam Hospital Bungeni Health Centre Watervall Clinic Lebowakgomo Hospital – Complex Central/Provincial tertiary Community Health Centre: Hospital/s: Lebowakgomo District Hospitals: None Primary Health Care Mokopane Regional Hospital Zebediela hospital Lebowakgomo zone B clinic Thabamoopo Pschiatry hospital Regional Hospital: None Mokopane Hospital – Complex Central/Provincial tertiary Hospital/s: None District Hospitals: Community Health Centre Primary Health Care Regional Hospitals Voortrekker Hopsital Thabaleshoba CHC Mokopane Zone 1 Mokopane Regional Hospital Mokopane Zone 2 Manyoga Clinic Letaba Hospital – Complex Central/Provincial tertiary Primary Health Care: None Hospital/s: None District Hospitals: Community Health Centre Regional Hospitals Kgapane Hospital Nkowankowa CHC Letaba Regional Hospital Van Velden Hospital Pietersburg/Mankweng-Seshego Hospital – Complex Central/Provincial tertiary Hospital/s District Hospitals: Community Healtcare Centre Primary Health Care Pietersburg Hospital/ Mankweng hospital Seshego Hospital Buite Clinic Seshego Clinic Regional Hospitals: None Evelyn Lekganyane Clinic Specialized Hospitals: Thabamoopo Pschiatry Mankweng Clinic Rethabile Clinic St Rita's – Complex Central/Provincial tertiary Community Healthcare Primary Health Care: None Hospital/s: None District Hospitals: Centre Regional Hospitals Jane Furse Hospital Phokoane -

FINAL Farms GVR EPHRAIM 01-01-2013

EPHRAIM MOGALE LOCAL MUNICIPALITY FARM Valuation roll for the period 1 July 2013 - 30 June 2017 Category determined in Registered or other description of the property Full Names of Owner(s) Extent in m² Market Value Remarks and any other prescribed particulars terms of Section 8 of the Act FARM_NAME ERF_NO REG_DIV PTN ARABIE KS 685 685 KS 0 GOVERNMENT OF LEBOWA AGRICULTURAL 1594.6042 36 480 000 CULTVATED LAND BLAUWWILDEBEESTFONTEIN 16 JS 16 JS 0 GERT SCHOONBEE BELEGGINGS PTY LTD, BACKHOFF EUGEN GEORG AGRICULTURAL 107.5518 750 000 BLAUWWILDEBEESTFONTEIN 16 JS 16 JS 1 HENDRIK SCHOEMAN & SEUNS DRONKFONTEIN PTY LTD, BACKHOFF AGRICULTURAL 287.7948 7 450 000 CULTIVATED LAND BLAUWWILDEBEESTFONTEIN 16 JS 16 JS 2 GERT SCHOONBEE BELEGGINGS PTY LTD, BACKHOFF EUGEN GEORG AGRICULTURAL 102.3742 720 000 BLAUWWILDEBEESTFONTEIN 16 JS 16 JS 3 GERT SCHOONBEE BELEGGINGS PTY LTD, BACKHOFF EUGEN GEORG AGRICULTURAL 77.3907 2 690 000 COMMERCIAL FARM BLAUWWILDEBEESTFONTEIN 16 JS 16 JS 4 GERT SCHOONBEE BELEGGINGS PTY LTD, BACKHOFF EUGEN GEORG AGRICULTURAL 106.9619 2 590 000 COMMERCIAL FARM BLAUWWILDEBEESTFONTEIN 16 JS 16 JS 7 GERT SCHOONBEE BELEGGINGS PTY LTD, BACKHOFF EUGEN GEORG AGRICULTURAL 68.2037 1 950 000 CULTIVATED LAND BLAUWWILDEBEESTFONTEIN 16 JS 16 JS 8 GERT SCHOONBEE BELEGGINGS PTY LTD, BACKHOFF EUGEN GEORG AGRICULTURAL 109.2074 1 630 000 CULTIVATED LAND BLAUWWILDEBEESTFONTEIN 16 JS 16 JS 10 HENDRIK SCHOEMAN & SEUNS DRONKFONTEIN PTY LTD, BACKHOFF AGRICULTURAL 310.3481 6 120 000 BLAUWWILDEBEESTFONTEIN 16 JS 16 JS 11 HENDRIK SCHOEMAN & SEUNS DRONKFONTEIN -

Capricorn District

01/52 2 PROFILE: CAPRICORN DISTRICT PROFILE: CAPRICORN DISTRICT 3 CONTENT 1 Executive Summary ........................................................................................... 6 2 Introduction: Brief Overview ............................................................................. 7 2.1 Location ................................................................................................................ 7 2.2 Historical Perspective ........................................................................................... 8 2.3 Spatial Status ....................................................................................................... 9 2.4 Land Ownership ................................................... Error! Bookmark not defined. 3 Social Development Profile ............................................................................. 11 3.1 Key Social Demographics .................................................................................. 11 3.1.1 Population and Household Profile .............................................................. 11 3.1.2 Race, Gender and Age profile .................................................................... 12 3.1.3 Poverty ......................................................... Error! Bookmark not defined. 3.1.4 Human Development Index and Gini coefficient ........................................ 17 3.1.5 Unemployment/Employment ...................................................................... 17 3.1.6 Education provision ................................................................................... -

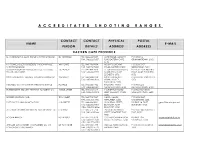

Accreditated Shooting Ranges

A C C R E D I T A T E D S H O O T I N G R A N G E S CONTACT CONTACT PHYSICAL POSTAL NAME E-MAIL PERSON DETAILS ADDRESS ADDRESS EASTERN CAPE PROVINCE D J SURRIDGE T/A ALOE RIDGE SHOOTING RANGE DJ SURRIDGE TEL: 046 622 9687 ALOE RIDGE MANLEY'S P O BOX 12, FAX: 046 622 9687 FLAT, EASTERN CAPE, GRAHAMSTOWN, 6140 6140 K V PEINKE (SOLE PROPRIETOR) T/A BONNYVALE WK PEINKE TEL: 043 736 9334 MOUNT COKE KWT P O BOX 5157, SHOOTING RANGE FAX: 043 736 9688 ROAD, EASTERN CAPE GREENFIELDS, 5201 TOMMY BOSCH AND ASSOCIATES CC T/A LOCK, T C BOSCH TEL: 041 484 7818 51 GRAHAMSTAD ROAD, P O BOX 2564, NOORD STOCK AND BARREL FAX: 041 484 7719 NORTH END, PORT EINDE, PORT ELIZABETH, ELIZABETH, 6056 6056 SWALLOW KRANTZ FIREARM TRAINING CENTRE CC WH SCOTT TEL: 045 848 0104 SWALLOW KRANTZ P O BOX 80, TARKASTAD, FAX: 045 848 0103 SPRING VALLEY, 5370 TARKASTAD, 5370 MECHLEC CC T/A OUTSPAN SHOOTING RANGE PL BAILIE TEL: 046 636 1442 BALCRAIG FARM, P O BOX 223, FAX: 046 636 1442 GRAHAMSTOWN, 6140 GRAHAMSTOWN, 6140 BUTTERWORTH SECURITY TRAINING ACADEMY CC WB DE JAGER TEL: 043 642 1614 146 BUFFALO ROAD, P O BOX 867, KING FAX: 043 642 3313 KING WILLIAM'S TOWN, WILLIAM'S TOWN, 5600 5600 BORDER HUNTING CLUB TE SCHMIDT TEL: 043 703 7847 NAVEL VALLEY, P O BOX 3047, FAX: 043 703 7905 NEWLANDS, 5206 CAMBRIDGE, 5206 EAST CAPE PLAINS GAME SAFARIS J G GREEFF TEL: 046 684 0801 20 DURBAN STREET, PO BOX 16, FORT [email protected] FAX: 046 684 0801 BEAUFORT, FORT BEAUFORT, 5720 CELL: 082 925 4526 BEAUFORT, 5720 ALL ARMS FIREARM ASSESSMENT AND TRAINING CC F MARAIS TEL: 082 571 5714 -

Contract Wp 9711 Development of a Reconciliation Strategy for All Towns in the Northern Region

CONTRACT WP 9711 DEVELOPMENT OF A RECONCILIATION STRATEGY FOR ALL TOWNS IN THE NORTHERN REGION GREATER SEKHUKHUNE DISTRICT MUNICIPALITY GREATER MARBLE HALL LOCAL MUNICIPALITIES: FIRST ORDER RECONCILIATION STRATEGY FOR FLAG BOSHIELO REGIONAL WATER SUPPLY SCHEME Flag Boshielo Settlements in the Eastern, Central and Western Clusters DRAFT VERSION 1.3 JUNE 2010 Prepared by Prepared for: SRK Consulting Department of Water Affairs PO Box 55291 Directorate: National Water Resources Planning NORTHLANDS Private Bag X313 2116 PRETORIA, Tel: +27 (0) 11 441 1111 0001 E-mail: [email protected] RECONCILIATION STRATEGY FOR FLAG BOSHIELO WS REPORT NO. {1} DEVELOPMENT OF A RECONCILIATION STRATEGY FOR ALL TOWNS IN THE NORTHERN REGION FIRST ORDER RECONCILIATION STRATEGY FOR FLAG BOSHIELO CENTRAL, FLAG BOSHIELO EASTERN 2 AND FLAG BOSHIELO EASTERN 3 WATER SUPPLY SCHEMES EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The rudimentary strategy objectives and methodology are presented in a separate report titled “ Starter document: Methodology followed for the Development of Reconciliation Strategies for the All Town Study Northern Region ” and must be read in conjunction with this document. Location and Background Information The focus of this document includes the settlements in the Flag Boshielo Water Supply System situated in the Eastern half of Greater Marble Hall Local Municipality. These settlements receive water from the Flag Boshielo Water Supply System. The Flag Boshielo Dam provides about 4 Water Supply Sub-Schemes including the sub schemes in Fetakgomo Local Municipality that also receive their supply from Flag Boshielo Dam through a weir in the Olifants River. Water is transported through a network of pipeline system to different rural villages in the above mentioned Local Municipality. -

From Gauteng.- to Marble Hall 185 KMS from SANDTON (Recommended Route) Drive Time Approx 2 Hours Take Pietersburg By-Pass Around Pretoria (N1)

From Gauteng.- to Marble Hall 185 KMS FROM SANDTON (Recommended Route) Drive time approx 2 hours Take Pietersburg by-pass around Pretoria (N1). The last exit on leaving Pretoria is Zambezi Drive (Exit 152). Take Zambezi off-ramp and turn RIGHT toward Cullinan at traffic light. (You are approx 125kms away) At the next traffic light turn LEFT at Kwa-mahlanga sign. Proceed straight. Approx 125kms.. Proceed until “Bush Fellow Game Lodge”/Vaalfontein sign, turn RIGHT onto sand. Travel next to water-furrow for 5km and turn RIGHT at bridge over canal with Lions on top of pillars. From N1 Settlers / Codrington to Marble Hall Drive time 2.5 hours After Carousel Casino on Warmbaths highway, take Settlers/Codrington offramp. Turn right over highway and continue for +- 120kms to north side of Marble Hall. From Marble Hall : From the north side, keep to the right and drive past Marble Hall town going over 3 stop streets. Continue going straight leaving Marble Hall in direction of Siyabuswa. Drive past airstrip on right and Golf course on left. After +-5km, turn left onto sand road at Bush Fellows sign. Follow road for +- 5km along water furrow. Lodge is on the right at bridge with Lions on top of orange coloured pillars. From Bronkhorstspruit : Pretoria / Witbank / Middelburg Turn off N4 highway at 2nd Bronkhorstspruit off ramp, toward Groblersdal. Travel in direction of Groblersdal. After 96km from highway, turn left at T-junction. Travel approx 17km until Dennilton, Bush Fellow Game Lodge sign. Turn left onto sand road. Left again at 1st T-junction. -

Robinson R44 ZS-PZZ Fatal 9160 Tmed__

Section/division Occurrence Investigation Form Number: CA 12-12a AIRCRAFT ACCIDENT REPORT AND EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Reference: CA18/2/3/9160 Aircraft ZS-PZZ Date of Accident 5 April 2013 Time of Accident 1630Z Registration Type of Type of Aircraft Robinson R44 II Raven (Helicopter) Private Flight Operation Commercial Pilot Pilot-in-command Licence Type Age 49 Licence Valid Yes Licence (CPL) Pilot -in -command Flying Total Flying Hours ± 7913,2 Hours on Type ± 2222,5 Experience Last point of departure Bela-Bela (private airfield) in Limpopo Province Next point of intended landing Roedtan (private airfield) in Limpopo Province Location of the accident site with reference to easily defined geographical points (GPS readings if possible) Nylstroom, near Bela-Bela in Limpopo province; GPS co-ordinates: S 24˚44’940” E028˚29’020”. Visibility: Low visibility, temperature:17˚, wind gusts: 20 kts, wind speed: 9 Meteorological Information kts. Number of people on 1 + 0 No. of people injured 0 No. of people killed 1 board Synopsis The pilot was the sole occupant on board the Robinson RH44 helicopter. He flew the helicopter from Bela- Bela to Roedtan. The pilot lost sight of the ground in the process of avoiding the thunderstorm. A thunderstorm intercepted the flight path to Roedtan. .The pilot was fatally injured. The helicopter was destroyed in the accident. An investigation determined that the pilot may have experienced spatial disorientation from which he could not recover. It resulted in the helicopter colliding with terrain (controlled flight into terrain – CFIT). The helicopter was investigated and no abnormality was identified with its operation, hence its operation was determined to be irrelevant to the accident.