Why Children and Youth Should Have the Right to Vote: an Argument for Proxy-Claim Suffrage Author(S): John Wall Source: Children, Youth and Environments, Vol

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Legal Protection of Youth Suffrage

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, volume 349 6th International Conference on Community Development (ICCD 2019) Legal Protection of Youth Suffrage Imam Ropii Hb. Sujiantoro University of Wisnuwardhana Malang University of Wisnuwardhana Malang [email protected] Abstract. As a large number of young voters still have The implementation of an accountable and responsive no identity card (Indonesian: Kartu Tanda democratic system of government embodied in each state Penduduk/KTP), the legal protection of youth policy formation always cooperates or involves people's suffrage is becoming a discourse by the General representation that has been elected and determined Election on 17 April 2019. Distribution of eligible through general elections [1]. citizens’ suffrage must be prevented from any According to Mahfud MD, the substance of the obstacles, mainly administrative issue. To the young democratic system places the people as the main subject voters, as the age when registering for the vote are not in every state policymaking through its representatives in old enough according to the law, the population the people's representative institutions [2]. administration office is unable to provide electronic The guarantee of the legal protection of citizens' identity cards (KTPE), resulting in them not being suffrage in general elections as regulated by the electoral registered as voters. The lack of electoral literacy and legal framework must be interpreted as an obligation to the constraints of administrative requirements make the government and elections organizers as well as the young voters vulnerable to losing their voting citizens to be realized. Likewise, the mass media plays a rights. A National Identification Number role as a controller and voicer if the implementation of (Indonesian: Nomor Induk Kependudukan, NIK) as the citizens' suffrage protection is hampered or cannot be the single identity number of each resident is listed on implemented due to the electoral law, population the family card (Indonesian: Kartu Keluarga, KK). -

19Th Amendment Conference | CLE Materials

The 19th Amendment at 100: From the Vote to Gender Equality Center for Constitutional Law at The University of Akron School of Law Friday, Sept. 20, 2019 CONTINUING EDUCATION MATERIALS More information about the Center for Con Law at Akron available on the Center website, https://www.uakron.edu/law/ccl/ and on Twitter @conlawcenter 001 Table of Contents Page Conference Program Schedule 3 Awakening and Advocacy for Women’s Suffrage Tracy Thomas, More Than the Vote: The 19th Amendment as Proxy for Gender Equality 5 Richard H. Chused, The Temperance Movement’s Impact on Adoption of Women’s Suffrage 28 Nicole B. Godfrey, Suffragist Prisoners and the Importance of Protecting Prisoner Protests 53 Amending the Constitution Ann D. Gordon, Many Pathways to Suffrage, Other Than the 19th Amendment 74 Paula A. Monopoli, The Legal and Constitutional Development of the Nineteenth Amendment in the Decade Following Ratification 87 Keynote: Ellen Carol DuBois, The Afterstory of the Nineteth Amendment, Outline 96 Extensions and Applications of the Nineteenth Amendment Cornelia Weiss The 19th Amendment and the U.S. “Women’s Emancipation” Policy in Post-World War II Occupied Japan: Going Beyond Suffrage 97 Constitutional Meaning of the Nineteenth Amendment Jill Elaine Hasday, Fights for Rights: How Forgetting and Denying Women’s Struggles for Equality Perpetuates Inequality 131 Michael Gentithes, Felony Disenfranchisement & the Nineteenth Amendment 196 Mae C. Quinn, Caridad Dominguez, Chelsea Omega, Abrafi Osei-Kofi & Carlye Owens, Youth Suffrage in the United States: Modern Movement Intersections, Connections, and the Constitution 205 002 THE CENTER FOR CONSTITUTIONAL LAW AT AKRON th The 19 Amendment at 100: From the Vote to Gender Equality Friday, September 20, 2019 (8am to 5pm) The University of Akron School of Law (Brennan Courtroom 180) The focus of the 2019 conference is the 100th anniversary of the 19th Amendment. -

Download Issue

YOUTH &POLICY No. 116 MAY 2017 Youth & Policy: The final issue? Towards a new format Editorial Group Paula Connaughton, Ruth Gilchrist, Tracey Hodgson, Tony Jeffs, Mark Smith, Jean Spence, Naomi Thompson, Tania de St Croix, Aniela Wenham, Tom Wylie. Associate Editors Priscilla Alderson, Institute of Education, London Sally Baker, The Open University Simon Bradford, Brunel University Judith Bessant, RMIT University, Australia Lesley Buckland, YMCA George Williams College Bob Coles, University of York John Holmes, Newman College, Birmingham Sue Mansfield, University of Dundee Gill Millar, South West Regional Youth Work Adviser Susan Morgan, University of Ulster Jon Ord, University College of St Mark and St John Jenny Pearce, University of Bedfordshire John Pitts, University of Bedfordshire Keith Popple, London South Bank University John Rose, Consultant Kalbir Shukra, Goldsmiths University Tony Taylor, IDYW Joyce Walker, University of Minnesota, USA Anna Whalen, Freelance Consultant Published by Youth & Policy, ‘Burnbrae’, Black Lane, Blaydon Burn, Blaydon on Tyne NE21 6DX. www.youthandpolicy.org Copyright: Youth & Policy The views expressed in the journal remain those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Editorial Group. Whilst every effort is made to check factual information, the Editorial Group is not responsible for errors in the material published in the journal. ii Youth & Policy No. 116 May 2017 About Youth & Policy Youth & Policy Journal was founded in 1982 to offer a critical space for the discussion of youth policy and youth work theory and practice. The editorial group have subsequently expanded activities to include the organisation of related conferences, research and book publication. Regular activities include the bi- annual ‘History of Community and Youth Work’ and the ‘Thinking Seriously’ conferences. -

Making Exceptions to Universal Suffrage: Disability and the Right to Vote

Making Exceptions to Universal Suffrage: Disability and the Right to Vote Kay Schriner, University of Arkansas Lisa Ochs, Arkansas State University In C.E. Faupel & P.M. Roman (Eds.), Encyclopedia of criminology and deviant behavior 179-183. London: Taylore & Francis. 2000. The history of Western representative democracies is marked by disputes over who constitutes the electorate. In the U.S., where states have the prerogative of establishing voter qualifications, categories such as race and gender have been used during various periods to disqualify millions of individuals from participating in elections. These restrictions have long been considered an infamous example of the failings of democratic theorists and practitioners to overcome the prejudices of their time. Less well-known is the common practice of disenfranchising other large numbers of adults. Indeed, very few American citizens are aware that there are still two groups who are routinely targeted for disenfranchisement - criminals and individuals with disabilities. These laws, which arguably perpetuate racial and disability discrimination, are vestiges of earlier attempts to cordon off from democracy those who were believed to be morally and intellectually inferior. This entry describes these disability-based disenfranchisements, and briefly discusses the political, economic, and social factors associated with their adoption. Disenfranchising People with Cognitive and Emotional Impairments Today, forty-four states disenfranchise some individuals with cognitive and emotional impairments. States use a variety of categories to identify such individuals, including idiot, insane, lunatic, mental incompetent, mental incapacitated, being of unsound mind, not quiet and peaceable, and under guardianship and/or conservatorship. Fifteen states disenfranchise individuals who are idiots, insane, and/or lunatics. -

A Political History of Youth in Twentieth-Century America

Bums, Revolutionaries, or Citizens? A Political History of Youth in Twentieth-Century America Allison D. Rank A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2014 Reading Committee: Mark A. Smith, Chair Leah M. Ceccarelli Jack Turner, III Naomi D. Murakawa Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Political Science 1 ©Copyright 2014 Allison D. Rank 2 University of Washington Abstract Bums, Revolutionaries, or Citizens? A Political History of Youth in Twentieth-Century America Allison D. Rank Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Professor Mark A. Smith Political Science Under what conditions do political elites begin to fear that young people will fail to become responsible citizens? What do these conditions and the solutions adopted tell us about the values and skills associated with American citizenship at specific points in time? What types of young people does the state try to develop into desirable citizens, and how has the state’s approach to youth who lie on the margins and are at risk of failing to adequately take on the role of citizen changed over time? How do changing beliefs, practices, and policies around youth and citizenship intersect with issues of race and state-building in America? To answer these questions, I examine key debates and policies from the Progressive Era through the 1970s. I focus on legislative initiatives, statements political actors made in support and opposition, and public and media reactions. I attend specifically to restrictions on child labor (1900s-1920s), the Civilian Conservation Corps (1934) and National Youth Administration (1935) during the New Deal, the G.I. -

The 2020 White Paper "Young Voices at the Ballot Box"

YOUNG VOICES AT THE BALLOT BOX Amplifying Youth Activism to Lower the Voting Age in 2020 and Beyond A White Paper from Generation Citizen (Version 3.0 – Feb. 2020) Young Voices at the Ballot Box: Amplifying Youth Activism to Lower the Voting Age 1 Young Voices at the Ballot Box: Amplifying Youth Activism to Lower the Voting Age 2 CONTENTS 03 Executive Summary 04 Why Should We Lower the Voting Age to 16? 08 Myths About Lowering the Voting Age 09 Current Landscape in the United States 17 Current Landscape Internationally 18 Next Steps to Advance this Cause 20 Conclusion 21 Appendix A: Countries with a Voting Age Lower than 18 22 Appendix B: Legal Feasibility of City Campaigns to Lower the Voting Age 34 Appendix C: Vote16USA Youth Advisory Board 35 Appendix D: Acknowledgements Cover Photo: Youth leaders, elected officials, and allies rally for a lower voting age on the steps of the California State Capitol in August 2019. Photo courtesy of Devin Murphy, California League of Conservation Voters. Young Voices at the Ballot Box: Amplifying Youth Activism to Lower the Voting Age 3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY BY EXPANDING THE RIGHT TO VOTE [TO 16- AND 17-YEAR-OLDS], MY COMMUNITY WILL BE ABLE TO FURTHER CREATE AN ATMOSPHERE “WHERE EACH NEW GENERATION GROWS UP TO BE LIFE-LONG VOTERS, WITH THE VALUE OF CIVIC ENGAGEMENT INSTILLED IN THEM. - Megan Zheng Vote16USA Youth Advisory Board Member e are on a mission to lower the voting possible. Sixteen is. As this paper outlines, age to 16. Democracy only works when inviting citizens into the voting booth at 16” will Wcitizens participate; yet, compared to strengthen American democracy by establishing other highly developed, democratic countries, voting as a lifelong habit among all citizens, and the U.S. -

Lessons Learned from the Suffrage Movement

University of Baltimore Law ScholarWorks@University of Baltimore School of Law All Faculty Scholarship Faculty Scholarship 6-3-2020 Lessons Learned From the Suffrage Movement Margaret E. Johnson Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.law.ubalt.edu/all_fac Part of the Law Commons Johnson, Margaret 6/3/2020 For Educational Use Only LESSONS LEARNED FROM THE SUFFRAGE MOVEMENT, 2 No. 1 Md. B.J. 115 2 No. 1 Md. B.J. 115 Maryland Bar Journal 2020 Margaret E. Johnsona1 PROFESSOR OF LAW, ASSOCIATE DEAN FOR EXPERIENTIAL EDUCATION, UNIVERSITY OF BALTIMORE SCHOOL OF LAW Copyright © 2020 by Maryland Bar Association; Margaret E. Johnson LESSONS LEARNED FROM THE SUFFRAGE MOVEMENT “Aye.” And with that one word, Tennessee Delegate Harry Burn changed his vote to one in favor of ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment after receiving a note from his mother stating “‘Hurrah and vote for suffrage .... don’t forget to be a good boy ....”’1 *116 With Burn’s vote on August 18, 1920, Tennessee became the thirty-sixth state to ratify the Nineteenth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution, paving the way for its adoption.2 The Nineteenth Amendment protects the female citizens’ constitutional right to vote.3 Prior to its passage, only a few states permitted women to vote in state and/or local elections.4 In 2020, we celebrate the Centennial of the Nineteenth Amendment’s passage. This anniversary provides a time to reflect upon lessons learned from the suffrage movement including that (1) voting rights matter; (2) inclusive movements matter; and (3) voting rights matter for, but cannot solely achieve, gender equality. -

How Effective Were the Suffragist and Suffragette Campaigns?

What were the arguments for and against female suffrage? Note: the proper name for votes for women is ‘Female Suffrage’ In the nineteenth century, new jobs emerged for women as teachers, as shop workers or as clerks and secretaries in offices. Many able girls from working-class backgrounds could achieve better-paid jobs than those of their parents. They had more opportunities in education., for example a few middle-class women won the chance to go to university, to become doctors. Laws between 1839 and 1886 gave married women greater legal rights. However, they could not vote in general elections. The number of men who could vote had gradually increased during the nineteenth century (see the Factfile). Some people thought that women should be allowed to vote too. Others disagreed. But the debate was not, simply a case of men versus women. How effective were the suffragist and suffragette campaigns? Who were the suffragists? The early campaigners for the vote were known as suffragists. They were mainly (though not all) middle-class women. When the MP John Stuart Mill had suggested giving votes to women in 1867, 73 MPs had supported it. After 1867, local groups set up by women called women’s suffrage societies were formed. By the time they came together in 1897 to form the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies (NUWSS), there were over 500 local branches. By 1902, the campaign had gained the support of working-class women as well. In 1901–1902, Eva Gore-Booth gathered the signatures of 67,000 textile workers in northern England for a petition (signed letter) to Parliament. -

What Is Suffrage? by Gwen Perkins, Edited by Abby Rhinehart

What is Suffrage? by Gwen Perkins, edited by Abby Rhinehart "Suffrage" means the right to vote. When citizens have the right to vote for or against laws and leaders, that government is called a "democracy." Voting is one of the most important principles of government in a democracy. Many Americans think voting is an automatic right, something that all citizens over the age of 18 are guaranteed. But this has not always been the case. When the United States was founded, only white male property owners could vote. It has taken centuries for citizens to achieve the rights that they enjoy today. Who has been able to vote in United States history? How have voting rights changed over time? Read more to discover some key events. 1789: Religious Freedom When the nation was first founded, several of the 13 colonies did not allow Jews, Quakers, and/or Catholics to vote or run for political office. Article VI of the Constitution was written and adopted in 1789, granting religious freedom. This allowed white male property owners of all religions to vote and run for political office. 1870: Men of All Races Get the Right to Vote At the end of the Civil War, the United States created another amendment that gave former male slaves the right to vote. The 15th Amendment granted all men in the United States the right to vote regardless of "race, color, or previous condition of servitude." This sounded good, but there was a catch. To vote in many states, people were still required to own land. -

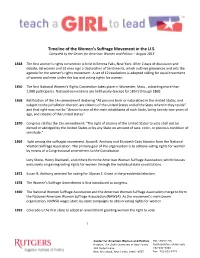

Timeline of the Women's Suffrage Movement in the U.S

Timeline of the Women’s Suffrage Movement in the U.S. Compiled by the Center for American Women and Politics – August 2014 1848 The first women's rights convention is held in Seneca Falls, New York. After 2 days of discussion and debate, 68 women and 32 men sign a Declaration of Sentiments, which outlines grievances and sets the agenda for the women's rights movement. A set of 12 resolutions is adopted calling for equal treatment of women and men under the law and voting rights for women. 1850 The first National Women's Rights Convention takes place in Worcester, Mass., attracting more than 1,000 participants. National conventions are held yearly (except for 1857) through 1860. 1868 Ratification of the 14th amendment declaring “All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside” and that right may not be “denied to any of the male inhabitants of such State, being twenty-one years of age, and citizens of the United States” 1870 Congress ratifies the 15th amendment: “The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.” 1869 Split among the suffragist movement. Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton form the National Woman Suffrage Association. The primary goal of the organization is to achieve voting rights for women by means of a Congressional amendment to the Constitution. -

End Women's Suffrage- a Brief Study on Violence Against

Corpus Juris ISSN: 2582-2918 The Law Journal website: www.corpusjuris.co.in END WOMEN’S SUFFRAGE- A BRIEF STUDY ON VIOLENCE AGAINST WOMEN. - DEVANSH GULATI1 AND DHRUV CHAUHDHRY2 ABSTRACT The Global Campaign for elimination of violence against women in the past few years shows the evilness as well as the soberness of the malfeasance committed against women that are being witnessed in the whole world. There has been an increase in crime against women due to a change in the social ethos which contributes towards a violent attitude and tendency towards women. Crimes against women are said to be a matter of serious concern and it is a necessity that the women of India attain the rightful share of living with dignity, freedom, peace and last but not the least free from crimes. The struggle against crime towards women through various ways which could be in the form of Marital Rape, Domestic Violence, Sexual Exploitation, Assault etc. had started in the early ages by various sections of the society. There were many initiatives which were taken up in the form of campaigns and various social programmes along with social support and legal protection which safeguards and reforms in the Criminal Justice System. All these safeguards went in vain as these women in our country still suffer due to lack of awareness about their rights, due to illiteracy, oppressive practices and customs. There were many consequences regarding the same which amounted to fall in sex ratio, high infant mortality rate, low literacy rate, high dropout rate of girls from education, low wage rate etc. -

The Legacy of Woman Suffrage for the Voting Right

UCLA UCLA Women's Law Journal Title Dominance and Democracy: The Legacy of Woman Suffrage for the Voting Right Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/4r4018j9 Journal UCLA Women's Law Journal, 5(1) Author Lind, JoEllen Publication Date 1994 DOI 10.5070/L351017615 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California ARTICLE DOMINANCE AND DEMOCRACY: THE LEGACY OF WOMAN SUFFRAGE FOR THE VOTING RIGHT JoEllen Lind* TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ............................................ 104 I. VOTING AND THE COMPLEX OF DOMINANCE ......... 110 A. The Nineteenth Century Gender System .......... 111 B. The Vote and the Complex of Dominance ........ 113 C. Political Theories About the Vote ................. 116 1. Two Understandings of Political Participation .................................. 120 2. Our Federalism ............................... 123 II. A SUFFRAGE HISTORY PRIMER ...................... 126 A. From Invisibility to Organization: The Women's Movement in Antebellum America ............... 128 1. Early Causes ................................. 128 2. Women and Abolition ........................ 138 3. Seneca Falls - Political Discourse at the M argin ....................................... 145 * Professor of Law, Valparaiso University; A.B. Stanford University, 1972; J.D. University of California at Los Angeles, 1975; Candidate Ph.D. (political the- ory) University of Utah, 1994. I wish to thank Akhil Amar for the careful reading he gave this piece, and in particular for his assistance with Reconstruction history. In addition, my colleagues Ivan Bodensteiner, Laura Gaston Dooley, and Rosalie Levinson provided me with perspicuous editorial advice. Special acknowledgment should also be given to Amy Hague, Curator of the Sophia Smith Collection of Smith College, for all of her help with original resources. Finally, I wish to thank my research assistants Christine Brookbank, Colleen Kritlow, and Jill Norton for their exceptional contribution to this project.