Wall Street Journal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

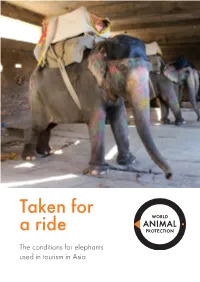

Taken for a Ride

Taken for a ride The conditions for elephants used in tourism in Asia Author Dr Jan Schmidt-Burbach graduated in veterinary medicine in Germany and completed a PhD on diagnosing health issues in Asian elephants. He has worked as a wild animal veterinarian, project manager and wildlife researcher in Asia for more than 10 years. Dr Schmidt-Burbach has published several scientific papers on the exploitation of wild animals as part of the illegal wildlife trade and conducted a 2010 study on wildlife entertainment in Thailand. He speaks at many expert forums about the urgent need to address the suffering of wild animals in captivity. Acknowledgment This report has only been possible with the invaluable help of those who have participated in the fieldwork, given advice and feedback. Thanks particularly to: Dr Jennifer Ford, Lindsay Hartley-Backhouse, Soham Mukherjee, Manoj Gautam, Tim Gorski, Dananjaya Karunaratna, Delphine Ronfot, Julie Middelkoop and Dr Neil D’Cruze. World Animal Protection is grateful for the generous support from TUI Care Foundation and The Intrepid Foundation, which made this report possible. Preface Contents World Animal Protection has been moving the world to protect animals for more than 50 years. Currently working in over Executive summary 6 50 countries and on 6 continents, it is a truly global organisation. Protecting the world’s wildlife from exploitation and cruelty is central to its work. Introduction 8 The Wildlife - not entertainers campaign aims to end the suffering of hundreds of thousands of wild animals used and abused Background information 10 in the tourism entertainment industry. The strength of the campaign is in building a movement to protect wildlife. -

Polo+10 World – the P Olo Magazine Est. 2004 I / 2012, V Olume 1

1 o N • WORLD olume 1 2012, V / I polo+10 world – The Polo Magazine • Est. 2004 www.poloplus10.com Printed in Germany I / 2012, Volume 1 • No 1 Est. 2004 • olo Magazine P 71,50 AED 86,50 ARS 19,50 AUD 7,50 BHD 18,50 CHF 123,00 CNY 15,00 EUR 12,50 GBP 150,50 HKD 1056,00 INR 1550,00 JPY 71,00 QAR 592,50 RUB 24,50 SGD 19,50 USD 157,00 ZAR polo+10 world – The Bucherer_Polo_Plus_10_Magazin_1-2012_englisch_RZ_Bucherer_Polo_Plus_10_Magazin_1-2012_englisch_RZ 26.04.12 16:43 Seite 1 EDITORIAL POLO +10 WORLD 3 ELEGANCE | PASSION POLO+10 WORLD Since 2004, POLO+10 has been reporting on Polo, main- ly in Europe, but starting now, our international editi- on POLO+10 WORLD will be published twice yearly. Polo is an international sport, a meeting place of all the cosmopolitans and a language that is spoken throughout the world. We are pleasant ly surprised that our friendships keep expan- ding across the globe. A Carousel of profes- sional athletes and enthusiasts, horse fanatics and ball acrobats is circumventing the world. Which is why, beginning now, we are relea- sing an international edition POLO+10 WORLD twice yearly. With this decision we are stik- king to a philosophy, one that has withstood the test of time, which we hold true ourselves. Polo players never get tired of quoting, “Polo is more than a sport. Polo is a way of life.” POLO+10 has followed this philosophy from the start. As a polo magazine we have our eyes set on the enthusiasts, on the sideline as well as on the field. -

Winter-2013.Pdf

Alumni Gazette WEStern’S ALUMNI MAGAZINE SINCE 1939 WINTER 2013 Power player TTC Chair Karen Stintz Alumni Gazette CONTENTS See public health from SAGT YIN on track 12 Karen Stintz, BA’92, Dipl’93, Chair of TTC a new vantage point STA Y THIRSTY 14 FOR ADVENTURE John Marcus Payne, LLB’73, has almost done it all OSCAR WINNER FIRST 16 MUSIC HALL OF FAMER Composer Barbara Willis Sweet, BMus’75 STOPPING YOUR OWN 18 GLOBAL WARMING Cardiologist & author Bradley J. Dibble, MD’90 W RITING code for 20 WEBSITES is fun? Web designer Amanda Aitken, BA’05, Cert’05 WHO IS WATCHING 26 THE POLICE? Director of Ontario’s SIU Ian Scott, LLB’81 NO JOKE: FAILURE CAN 30 LEAD TO SUCCESS Comedian and writer Deepak Sethi, BSc’02 The new Master of Public Health. 26 Get ready to lead. DEPARTMENTS @ alumnigazette.ca LETTERS CONSUMER GUIDE 05 Impressed by student spirit 28 Top 5 wines to drink now at Homecoming MAKING THE FRENCH CONNECTION BEST KEPT SECRET P URSUING JOINT PHD LIFE-ALTERING CAMPUS NEWS 32 Famous signatures in Western EXPERIENCE for KristEN SNELL, BSC’09, 07 Clinical trials of AIDS vaccine Archives MSC’11 making progress THE ROAD TO HOLLYWOOD NEW RELEASES Q & A WITH COMEDY WRITER DEEPAK SETHI, 36 Save the Humans by Rob CAMPUS QUOTES BSC’02 09 Western hosts guest speakers Stewart, BSc’01 A CAREER OF PERSISTANCE MEMORIES GAZETTEER AN EXpaNDED story ON DR. Masashi • 12 months full-time APPLY NOW • Deadline March 1 22 Winter Carnival on UC Hill 41 Alumni notes & Kawasaki, BA’53, MD’57 • intensive case-based learning schulich.uwo.ca/publichealth announcements SAVE THE HUMANS – EXCERPT • interdisciplinary faculty BY ROB STEWART, BSC’01 • 12-week practicum On the cover: Karen Stintz, BA’92, Dipl’93 (Political Science, King’s) is chair of the Toronto • international field trip Transit Commission (TTC). -

Global Insight A1 Module 3

GLOBAL INSIGHT A1 MODULE 3 Circle the correct item 1. My parents ............. eat breakfast. It’s the most important meal. A) always B) never C) sometimes D) rarely 2. His brother likes sleeping. He can .............. wake up before 10 o’clock. A) often B) always C) seldom D) never 3. A :.............................. B : Honestly, I seldom help with it. A) Do you help with your mother ? B) Do you often tidy up your bedroom ? C) How often do you help with the housework ? D) I take bus to work. 4. How .......... do you surf the Internet? A) often B) usually C) sometimes D) occasionally 5. ........................and then you can go to bed. A) Brush your teeth ! B) Push harder ! C) Do better ! D) Don’t give up ! 6. ..........................the oven door and put the meat inside. A) Turn on B) Open C) Close D) Break 7. The child isn’t ..................... the dark. A) fearless B) afraid of C) challenging D) dull 8. Which sport is extreme ? A) cricket B) elephant polo C) wingsuit flying D) sepak takraw 9. What ‘s the opposite of ‘ traditional ‘ ? A) exhilarating B) wrong C) modern D) illegal 10. What do oil wrestlers wear during the match ? A) olive oil B) special suit C) kispet D) traditional clothes 11. Dr: What can I do for you? What’s the matter ? Mike: ....................................................... Dr: Well, mix salt with warm water and gargle with it. But don’t swallow it. A) I have got a sore throat . B) I have got a bad headache. C) I have got a runny nose. -

Taken for a Ride Report

Taken for a ride The conditions for elephants used in tourism in Asia Preface We have been moving the world to protect animals for more than 50 years. Currently working in more than 50 countries and on six continents, we are a truly global organisation. Protecting the world’s wildlife from exploitation and cruelty is central to our work. The Wildlife – not entertainers campaign aims to end the suffering of hundreds of thousands of wild animals used and abused in the tourism entertainment industry. The strength of the campaign is in building a movement to protect wildlife. Travel companies and tourists are at the forefront of taking action for elephants, and other wild animals. Moving the travel industry In 2010 TUI Nederland became the first tour operator to stop all sales and promotion of venues offering elephant rides and shows. It was soon followed by several other operators including Intrepid Travel who, in 2013, was first to stop such sales and promotions globally. By early 2017, more than 160 travel companies had made similar commitments and now offer elephant-friendly tourism activities. TripAdvisor announced in 2016 that it would end the sale of tickets for wildlife experiences where tourists come into direct contact with captive wild animals, including elephant riding. This decision was in response to 550,000 people taking action with us to demand that the company stop profiting from the world’s cruellest wildlife attractions. Yet these changes are only the start. There is much more to be done to save elephants and other wild animals from suffering in the name of entertainment. -

Zerohack Zer0pwn Youranonnews Yevgeniy Anikin Yes Men

Zerohack Zer0Pwn YourAnonNews Yevgeniy Anikin Yes Men YamaTough Xtreme x-Leader xenu xen0nymous www.oem.com.mx www.nytimes.com/pages/world/asia/index.html www.informador.com.mx www.futuregov.asia www.cronica.com.mx www.asiapacificsecuritymagazine.com Worm Wolfy Withdrawal* WillyFoReal Wikileaks IRC 88.80.16.13/9999 IRC Channel WikiLeaks WiiSpellWhy whitekidney Wells Fargo weed WallRoad w0rmware Vulnerability Vladislav Khorokhorin Visa Inc. Virus Virgin Islands "Viewpointe Archive Services, LLC" Versability Verizon Venezuela Vegas Vatican City USB US Trust US Bankcorp Uruguay Uran0n unusedcrayon United Kingdom UnicormCr3w unfittoprint unelected.org UndisclosedAnon Ukraine UGNazi ua_musti_1905 U.S. Bankcorp TYLER Turkey trosec113 Trojan Horse Trojan Trivette TriCk Tribalzer0 Transnistria transaction Traitor traffic court Tradecraft Trade Secrets "Total System Services, Inc." Topiary Top Secret Tom Stracener TibitXimer Thumb Drive Thomson Reuters TheWikiBoat thepeoplescause the_infecti0n The Unknowns The UnderTaker The Syrian electronic army The Jokerhack Thailand ThaCosmo th3j35t3r testeux1 TEST Telecomix TehWongZ Teddy Bigglesworth TeaMp0isoN TeamHav0k Team Ghost Shell Team Digi7al tdl4 taxes TARP tango down Tampa Tammy Shapiro Taiwan Tabu T0x1c t0wN T.A.R.P. Syrian Electronic Army syndiv Symantec Corporation Switzerland Swingers Club SWIFT Sweden Swan SwaggSec Swagg Security "SunGard Data Systems, Inc." Stuxnet Stringer Streamroller Stole* Sterlok SteelAnne st0rm SQLi Spyware Spying Spydevilz Spy Camera Sposed Spook Spoofing Splendide -

Furman Magazine. Volume 52, Issue 1 - Full Issue Furman University

Furman Magazine Volume 52 Article 1 Issue 1 Spring 2009 4-1-2009 Furman Magazine. Volume 52, Issue 1 - Full Issue Furman University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarexchange.furman.edu/furman-magazine Recommended Citation University, Furman (2009) "Furman Magazine. Volume 52, Issue 1 - Full Issue," Furman Magazine: Vol. 52 : Iss. 1 , Article 1. Available at: https://scholarexchange.furman.edu/furman-magazine/vol52/iss1/1 This Complete Volume is made available online by Journals, part of the Furman University Scholar Exchange (FUSE). It has been accepted for inclusion in Furman Magazine by an authorized FUSE administrator. For terms of use, please refer to the FUSE Institutional Repository Guidelines. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SPRING 2009 FOR ALUMNI AND FRIENDS OF THE UNIVERSITY Golden Anniversary PAGE 2 Furman FOR ALUMNI AND FRIENDS OF THE UNIVERSITY SPRING 2009 Volume 52, Number 1 Furman magazine is published quarterly for alumni and friends by the Office of Marketing and Public Relations, Furman University, Greenville, S.C. 29613. FEATURES EDITOR Jim Stewart 2 A Greater Furman DESIGNER Jane A. Dorn BY JUDITH T. BAINBRIDGE The 2008-09 academic year marked the 50th anniversary of Furman’s move to the current CONTRIBUTORS Judith T. Bainbridge campus. Here’s a look back at the early days. Eleanor Beardsley Jeffrey C. Bollerman Dudley Brown 8 Rumble in the Jungle Kate Hofler BY JEFFREY C. BOLLERMAN Liz McSherry An international competition to determine the World Elephant Polo Championship? Vince Moore Indeed. And an alumnus was there to describe it all. Candace O’Connor Josie Sawyer 14 Gladly Wolde He Lerne and Gladly Teche Tom Triplitt BY JIM STEWART Lauren Tyler Wright A tribute to the leadership and legacy of Francis W. -

40Plus Games

NAME TOSS Throw the tennis ball around the circle. As you throw it, announce your name VERY loudly and HELLO keep going until everyone has had a chance to make their bold introduction. Now change it up – instead of announcing your name to the “royal ball” say the name of the person to whom you are throwing the ball. Change positions in the circle and try again. INTRODUCTION CIRCLES You may be nervous when meeting someone for the first time. Pretend the ball is large emerald jewel from the Royal Treasury. Group members number off as a “1” or “2” or by “toilet paper folders” and “toilet paper crumplers.” Each group chooses a leader, and then choose which group will get the jewel first. That group’s leader then presents the jewel to someone in the “un-jeweled” group, who must dazzle the giver with 45 seconds of valuable personal information. Leaders should feel free to give some topics for conversation. After the time is up, jewel recipients then present the jewel to someone in the other group for new introductions. Repeat until all have spoken. MAGIC TRANSFORMING TENNIS BALL Every medieval kingdom has a good old wizard hanging around. Merlin (the leader) begins with the tennis ball and tosses it to another “magician-in-training” in the group. As it is tossed, Merlin casts a hand in a spell-enchanting fashion while shouting out the name of a new object. The ball is now “transformed” into that object. Each time, the conversion “spell” must create an object just a little bit bigger than its current size. -

Class of 2012 Completing Their Work Experience with Us

MSA CLASS Master of Advanced Studies in Sports OF 2012 Administration and Technology The AISTS MSA is co-signed by MSA Master of Advanced Studies in Sports Administration and Technology www.aists.org/msa AISTS MSA The AISTS MSA, a unique programme Organised by the AISTS (International Academy of Sports Science and Technology), the AISTS MSA is a unique postgraduate programme in sports management held annually in Lausanne, the Olympic Capital. Over the course of one year, participants are trained by experts in sports and academics, in the following multi-disciplinary fi elds applied directly to sport: - Management & Economics - Technology - Law - Sociology - Medicine 2 The AISTS MSA degree is co-signed by some of the best academic and technology institutes of Switzerland: The Ecole Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne (EPFL), the University of Lausanne, the University of Geneva and the Swiss Graduate School of Public Administration (IDHEAP). The AISTS MSA is aimed at sports-minded professionals wishing to achieve a stronger skill set for their existing or desired career in the sports industry. Candidates to the programme are fl uent in English, have an undergraduate degree, a master’s degree and/or work experience, and are interested in developing or strengthening a career in sports management. Programme participants come from a wide range of nationalities and professions, but they all have the same goal of Mastering Sport. The AISTS MSA is co-signed by 3 AISTS MSA AISTS MSA work experience requirements In addition to course requirements, candidates for the AISTS MSA degree must also complete at least the equivalent of eight weeks of full time work in the sports industry. -

List of Sports

List of sports The following is a list of sports/games, divided by cat- egory. There are many more sports to be added. This system has a disadvantage because some sports may fit in more than one category. According to the World Sports Encyclopedia (2003) there are 8,000 indigenous sports and sporting games.[1] 1 Physical sports 1.1 Air sports Wingsuit flying • Parachuting • Banzai skydiving • BASE jumping • Skydiving Lima Lima aerobatics team performing over Louisville. • Skysurfing Main article: Air sports • Wingsuit flying • Paragliding • Aerobatics • Powered paragliding • Air racing • Paramotoring • Ballooning • Ultralight aviation • Cluster ballooning • Hopper ballooning 1.2 Archery Main article: Archery • Gliding • Marching band • Field archery • Hang gliding • Flight archery • Powered hang glider • Gungdo • Human powered aircraft • Indoor archery • Model aircraft • Kyūdō 1 2 1 PHYSICAL SPORTS • Sipa • Throwball • Volleyball • Beach volleyball • Water Volleyball • Paralympic volleyball • Wallyball • Tennis Members of the Gotemba Kyūdō Association demonstrate Kyūdō. 1.4 Basketball family • Popinjay • Target archery 1.3 Ball over net games An international match of Volleyball. Basketball player Dwight Howard making a slam dunk at 2008 • Ball badminton Summer Olympic Games • Biribol • Basketball • Goalroball • Beach basketball • Bossaball • Deaf basketball • Fistball • 3x3 • Footbag net • Streetball • • Football tennis Water basketball • Wheelchair basketball • Footvolley • Korfball • Hooverball • Netball • Peteca • Fastnet • Pickleball -

Annapurna Challenge

Annapurna Challenge Supporting Girlguiding Hampshire West’s 2017 Expedition to Nepal and women’s health in Nepal. Annapurna Challenge Members of Girlguiding Hampshire We will be taking basic medical supplies West are visiting Nepal in April 2017 to with us to give to local Nepalese women trek the Annapurna trail. Thank you who have no access to even the most for supporting us through this basic of health care. challenge. Contents This challenge consists of five sections, one for each colour in the Nepalese prayer flags, and is suitable for Rainbows, Brownies, Guides and the Senior Section (not forgetting the Trefoil Guild) Units should complete one challenge from each section to gain the badge. Ideas are themed around Nepal and its culture. Please feel free to adapt the challenges to suit the girls in your units. We hope you enjoy our challenge and thank you showing an interest. Nepalese Culture Go Outdoors Crafts Games Have a go at this Appendices Badge Order Form Nepalese Culture 1. Try some Nepalese food - Cook or try the national dish Dal Bhat - Or use the traditional ingredients of rice, lentils and curried vegetables to make your own dish. - Try eating with no cutlery using just your right hand (your left hand is thought to be unclean) - Have a tasting evening of Nepalese food. (See appendix for recipe suggestions) 2. Visit a Nepalese Restaurant 3. Make Nepalese Prayer Flags - Prayer flags are often seen flying from temples in Nepal – have a go at making your own – colour in our template or make your own from scraps of material, perhaps decorate with fabric pens or try other techniques. -

Insurance Policy Wording

Travel Plus Single Trip & Annual Multi-trip Travel Insurance Policy Wording REF: Travel Plus/PW/2021.0121 Chaucer Syndicates Edition: 0121 Contents Contacting Us 3 Sections of cover: Schedule of Benefits - Single Trip & Annual Multi-trip 4 1. Emergency Medical Assistance & Expenses 18 Information for the Entire Policy 5 - 6 2. Personal Accident 19 Eligibility 6 3. Baggage 19 Geographical Areas 6 4. Cancellation & Cutting Short a Trip 19 - 20 Our Complaints Procedure 7 5. Travel Delay, Missed Departure & Missed Connection 20 - 21 Data Protection Statement 7 - 9 6. Passport, Documents or Driving Licence 21 Assistance Service 9 - 10 7. Personal Money 21 - What to do in the case of a medical emergency abroad 8. Personal Liability 21 Reciprocal Health Arrangements 10 9. Legal Expenses 21 - 22 How to Make a Claim 10 - 11 10. Baggage Delay 22 - Claim Checklist 11. Travel Risks 22 Important Exclusions and Conditions Relating to Health 11 - Be Aware 12. Extended Journey Disruption 22 - 23 - Medical Screening 13. End Supplier Failure Insurance 23 - IMPORTANT – Change in State of Health 14. Winter Sports Cover 24 Activities 12 - 14 15. Cruise Cover 24 - 25 Definitions 14 - 16 16. Business Cover 25 - 26 Conditions 16 - 17 17. Gadget Cover 26 - 27 Exclusions 17 - 18 18. Travel Consumer Dispute 27 - 29 Useful Information 29 2 Contacting Us If you have any questions about your policy, please contact us at www.travelplusinsurance.co.uk or call us on: 023 9241 9050 for Brokers, Monday to Friday 9am-5pm, closed Bank Holidays, or 023 9241 9006 for Direct Customers, Monday to Friday 9am-5pm, closed Bank Holidays Contacting us to notify us of an emergency or make a claim under this policy could not be easier.