Michael N. Pearson: a Partnership Across the Oceans

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter Twelve Jesuit Schools and Missions in The

CHAPTER TWELVE JESUIT SCHOOLS AND MISSIONS IN THE ORIENT 1 MARIA DE DEUS MANSO AND LEONOR DIAZ DE SEABRA View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Missions in India brought to you by CORE provided by Repositório Científico da Universidade de Évora The Northern Province: Goa 2 On 27 th February 1540, the Papal Bull Regimini Militantis Eclesiae established the official institution of The Society of Jesus, centred on Ignacio de Loyola. Its creation marked the beginning of a new Order that would accomplish its apostolic mission through education and evangelisation. The Society’s first apostolic activity was in service of the Portuguese Crown. Thus, Jesuits became involved within the missionary structure of the Portuguese Patronage and ended up preaching massively across non-European spaces and societies. Jesuits achieved one of the greatest polarizations and novelties of their charisma and religious order precisely in those ultramarine lands obtained by Iberian conquest and treatises 3. Among other places, Jesuits were active in Brazil, India, Indonesia, Malaysia, Japan and China. Their work gave birth to a new concept of mission, one which, underlying the Society’s original evangelic impulses, started to be organised around a dynamic conception of “spiritual conquest” aimed at converting to the Roman Catholic faith all those who “simply” ignored or had strayed from Church doctrines. In India, Jesuits created the Northern (Goa) and the Southern (Malabar) Provinces. One of their characteristics was the construction of buildings, which served as the Mission’s headquarters and where teaching was carried out. Even though we have a new concept of college nowadays, this was not a place for schooling or training, but a place whose function was broader than the one we attribute today. -

Identitarian Spaces of the Goan Diasporic Communities

Identitarian Spaces of the Goan Diasporic Communities Thesis Submitted to Goa University For the award of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy In English by Ms. Leanora Madeira née Pereira Under the Guidance of Prof. Nina Caldeira Department of English Goa University, Taleigao Plateau, Goa. India-403206 August, 2020 CERTIFICATE I hereby certify that the thesis entitled “Identitarian Spaces of Goan Diasporic Communities” submitted by Ms. Leanora Pereira for the award of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English, has been completed under my supervision. The thesis is a record of the research work conducted by the candidate during the period of her study and has not previously formed the basis for the award of any degree, diploma or certificate of this or any other University. Prof. Nina Caldeira, Department of English, Goa University. ii Declaration As required under the Ordinance OB 9A.9(v), I hereby declare that this thesis titled Identitarian Spaces of the Goan Diasporic Communities is the outcome of my own research undertaken under the guidance of Professor Dr. Nina Caldeira, Department of English, Goa University. All the sources used in the course of this work have been duly acknowledged in this thesis. This work has not previously formed the basis of any award of Degree, Diploma, Associateship, Fellowship or any other titles awarded to me by this or any other university. Ms. Leanora Pereira Madeira Research Student Department of English Goa University, Taleigao Plateau, Goa. India-403206 Date: August 2020 iii Acknowledgement The path God creates for each one of us is unique. I bow my head to the Almighty acknowledging him as the Alpha and the Omega and Lord of the Universe. -

Contribution of Jesuits to Higher Education in Goa: Historical Background of Higher Education of the Jesuits

CONTRIBUTION OF JESUITS TO HIGHER EDUCATION IN GOA: HISTORICAL BACKGROUND OF HIGHER EDUCATION OF THE JESUITS Savio Abreu, SJ Xavier Centre of Historical Research, Goa 1. Historical Background of Higher Education of the Jesuits Higher education has been synonymous with the Society of Jesus. The founding members of the Society, be it Ignatius or Francis Xa- vier were all University educated and right from the beginning, when the Society was founded on 27th September 1540, Ignatius stressed on a rigorous academic formation for all those who desired to become Jesuits. This tradition of higher education was seen in the Indian subcontinent right from the time when Francis Xavier landed in Goa on 6th May 1542. On his arrival he was requested to take up the responsibility of forming the youth of the seminary as he himself had adorned a chair at the Paris University. On 24th April 1541 the Vicar General of Goa, Miguel Vas and Fr. Diogo de Borba started the Confraternity of the Holy faith. The Confraternity was to propagate the catholic faith and to educate the young converts. It was also decided to establish a seminary for the indigenous boys, where they would be instructed in reading, writing, Portuguese and Latin grammar, Christian doctrine and moral theol- ogy. The work on the seminary of Holy Faith started on 10th November 1541, adjacent to the Church of Our Lady of Light in In/En: St Francis Xavier and the Jesuit Missionary Enterprise. Assimilations between Cultures / San Francisco Javier y la empresa misionera jesuita. Asimilaciones entre culturas, ed. Ignacio Arellano y Carlos Mata Induráin, Pamplona, Servicio de Publicaciones de la Universidad de Navarra, 2012 (BIADIG, Biblioteca Áurea Digital-Publicaciones digitales del GRISO), pp. -

Transoceanic Creolization and the Mando of Goa*

Modern Asian Studies , () pp. –. © The Author(s), . Published by Cambridge University Press. This is an Open Access article, distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution licence (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/./), which permits unrestricted re-use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. doi:./SX First published online January Rapsodia Ibero-Indiana: Transoceanic creolization and the mando of Goa* ANANYA JAHANARA KABIR Department of English, King’s College London Email: [email protected] Abstract The mando is a secular song-and-dance genre of Goa whose archival attestations began in the s.Itisstilldancedtoday,instagedratherthansocialsettings.Itslyricsarein Konkani, their musical accompaniment combine European and local instruments, and its dancing follows the principles of the nineteenth-century European group dances known as quadrilles, which proliferated in extra-European settings to yield various creolized forms. Using theories of creolization, archival and field research in Goa, and an understanding of quadrille dancing as a social and memorial act, this article presents the mando as a peninsular, Indic, creolized quadrille. It thus offers the first systematic examination of the mando as a nineteenth-century social dance created through * This article is based on fieldwork in Goa (field visits made in September , December , June ), as well as multiple field visits to Cape Verde, Brazil, Mozambique, Angola, and Lisbon (–), which have enabled me to comprehend music and dance across the Portuguese-speaking world. I have also drawn on fieldwork on the quadrille in the Indian Ocean (Mauritius, Seychelles, and Réunion, October– November ). All research fieldwork (except that in Angola) was done through ERC Advanced Grant funding. -

The Global Career of Indian Opium and Local Destinies

52 The Global Career of Indian Opium and Local Destinies DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/2236-463320161404 Amar Farooqui Department of History, University of Delhi, Delhi [email protected] Abstract: As is well known, opium was a major colonial commodity. It was linked to trade in several other commodities of the modern era such as tea, sugar and cotton and through these to Atlantic the slave trade. The movement of these commodities across continents shaped capitalism in very specific ways. In the case of India, for instance, earnings from the several components of the opium enterprise played an important role in the growth of industrial capitalism. This paper looks at the historical circumstances in which various localities and regions of the Indian subcontinent, especially western India, and the Indian Ocean became part of the opium enterprise during the early nineteenth century. It attempts to understand the manner in which local destinies were linked to the global, reinforcing and/or resisting British imperial interests. For this purpose I have chosen the port of Daman, on the West Coast of India as a representative example. Daman (Damaõ) was a Portuguese colony. The paper pays close attention to political processes at the local level so as to make sense of global patterns of trade in a commodity that was vital for sustaining the British Empire. Keywords: Opium, Malwa, Daman, Smuggling, Estado da Índia, Macau, Bombay, Tea, East India Company, colonial commodities Almanack. Guarulhos, n.14, p.52-73 dossiê scales of global history 53 Colonial commodities created conditions that can be better understood in a global context and by scrutinizing the interconnections between developments in different parts of the world. -

'Lord of Conquest, Avigation and Commerce' Diplomacy

‘Lord of Conquest, avigation and Commerce’ Diplomacy and the Imperial Ideal During the Reign of John V, 1707-1750 João Vicente Carvalho de Melo Submitted to Swansea University in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Swansea University 2012 ii iii Summary This dissertation explores the diplomatic practices of the Portuguese Estado da Índia in the first half of the eighteenth century, a period when the Portuguese imperial project in the Indian Ocean faced drastic changes imposed by the aggressive competition of the European rivals of the Estado and local powers such as the Marathas or the Omani. Based on documents from the Biblioteca Nacional de Portugal (Lisbon), the Biblioteca da Ajuda, the Academia das Ciências de Lisboa, the Arquivo Histórico Ultramarino, the British Library and the Historical Archives of Goa, this research suggests that diplomatic practices of the Portuguese Estado da Índia were not only concerned with protecting the interests of the Portuguese Crown in the West Coast of India, but were a part of a strategy designed to promote a prestigious reputation for the Portuguese Crown in the region despite the ascendancy of other European imperial powers. Besides a detailed analysis and description of the processes and circumstances by and which diplomatic contacts between local sovereigns and the Portuguese colonial administration were established, the rituals and language of diplomatic ceremonies with Asian sovereigns were also examined in detail in order to give a precise account of the ways in which Portuguese diplomats presented the Portuguese Crown to Asian rulers. iv Declarations and Statements This work has not previously been accepted in substance for any degree and is not being concurrently submitted in candidature for any degree. -

DOE Ela ADD DETEDNEE OM (20 - '1103'11

DOE Ela ADD DETEDNEE OM (20 - '1103'11 by Maria Fatima L. T. da Silva Gracias Thesis submitted to the Goa University for the degree of Doctor of Phifosophj in kistorj 54.791 under the guidance of Dr. Teotonio R. de Souza D i rector Xavier Centre of Historical Research, Goa. Goa, INDIA 1992 A statement under Ordinance 0.770 I hereby state that the research work carried out by me for the Ph.D. thesis entitled Health and Hygiene in Goa 1510-1961 is my original work. I am also to state that have not been awarded any degree or diploma or any other academic award by this or any other University or body for the thesis to be submitted by me. A statement under Ordinance 0.771 This thesis on "Health and Hygiene in Goa, 1510-1961" contains an historical inquiry into the conditions and problems of health and hygiene during the period of the Portuguese colonial rule in Goa. I have gone through the existing and relevant published works related directly and indirectly to different aspects of this theme, but the substance of the present research is drawn from archival documentation and from published contemporary reports. This has enabled to provide for the first time a comprehensive picture of the Goan Society from the perspective of health and hygiene and related issues. In the process much documentary evidence is also made available for understanding the socio- economic conditions of life in Goa during the period covered by this study. It is hoped that the contribution made by this thesis will enable those concerned about improving the quality of life in Goa to understand better the necessary background that has influenced and shaped many social attitudes and institutional strengths as well as handicaps. -

Valentino Viegas, As Políticas Portuguesas Na India E O Foral De Goa [=The

Valentino Viegas, As Políticas Portuguesas na India e o Foral de Goa [=The Portuguese Policies in India and the Charter of Goa], Lisboa, Livros Horizonte, 2005, pp.125 The book was released at Casa de Goa, Lisbon, by Dr. Nuno Gonçalves, a grandson of the last Portuguese governor-general of Goa till 1961. After two initial chapters covering the story of the Portuguese arrival in India and their use of force whenever cultural and economic conflicts did not permit a more peaceful control of the trade in the Indian Ocean, from page 45 onwards the author takes up the study of the Foral or the Charter of Rights and Obligations granted by the Portuguese administration to native Goans in 1526. The author states that some earlier historians like Filipe Nery Xavier Cunha Rivara and Teotonio de Souza utilised the versions available in Goa and did not care to consult the "original". He comes however to the conclusion that the version available at the National Archives of Lisbon is not the "original” either, but only a "registo", which he decided to transcribe in Chapter IV (pp. 85-93), modernizing the text in a way that hardly helps anyone to read it better or more usefully. A facsimile reproduction alongside the transcription would have been more useful for an informed and critical reader. Unfortunately this unhelpful transcription is accompanied by a less helpful genealogy and analysis of this manuscript version of the Foral available at the National Archives of Lisbon in *Gavetas 20-10-13*. The author does not mention, and obviously does not correct the reference to it in 1964 as “original” by another writer of Goan origin, Carlos Renato Gonçalves Pereira, História da Administração da Justiça no Estado da India - Séc. -

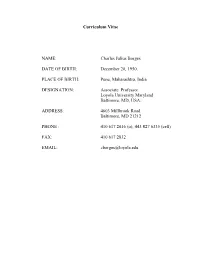

Curriculum Vitae NAME: Charles Julius Borges DATE of BIRTH

Curriculum Vitae NAME: Charles Julius Borges DATE OF BIRTH: December 20, 1950. PLACE OF BIRTH: Pune, Maharashtra, India DESIGNATION: Associate Professor Loyola University Maryland Baltimore, MD, USA. ADDRESS: 4603 Millbrook Road Baltimore, MD 21212 PHONE : 410 617 2016 (o); 443 827 6335 (cell) FAX: 410 617 2832 EMAIL: [email protected] ACADEMIC RECORD: DEGREE YEAR DISCIPLINE UNIVERSITY B. Lib. Sc. 1993 Library Science IGNOU (New Delhi) Ph.D. 1989 History Univ. of Bombay M.A. 1983 History Univ. of Bombay B.A 1977 English M.S. University (Baroda) POSITIONS HELD (Xavier Center of Historical Research, Goa, India) : Director: April 1994-December 2000 Ph.D. guide (Goa University) October 1998 onwards Associate Director: June 1993-April 1994. Librarian: 1990-1992. Administrator and Treasurer-Secretary: August 1981-June 1993. Administrative Assistant: June 1981-July 1981. (Loyola University Maryland, Baltimore) Director of the Loyola Bangkok Program from 2016 till 2018 for 38,28, 29 students respectively. Also taught segments of the course on Interfaith Dialogue at Assumption University during these years. Led and conducted three student tours to India in the Winter breaks of 2005, 2006 and 2007 for about 34 students in all. The idea was to acquaint them with Indian life and culture at close hand. The work entailed planning and executing almost single handedly all matters relating to travel, stay and visits and personal matters of students. While at Loyola, have taught English and religion to Jesuit students at their University at Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam, for one month during each of the years 2010, 2011, 2012, 2014. I have been Core Advisor and Major Advisor for history students at Loyola since 2003 till 2014. -

SANTOS, Joaquim Rodrigues Dos. “Cultural Idiosyncrasies and Preservation Challenges in the Indo-Portuguese Catholic Religious Architecture of Goa (India)”

SANTOS, Joaquim Rodrigues dos. “Cultural Idiosyncrasies and Preservation Challenges in the Indo-Portuguese Catholic Religious Architecture of Goa (India)”. In: SANTOS, Joaquim Rodrigues dos (ed.). Preserving Transcultural Heritage: Your Way or My Way?. Casal de Cambra: Caleidoscópio, 2017, pp.283-294. CULTURAL IDIOSYNCRASIES AND PRESERVATION CHALLENGES IN THE INDO-PORTUGUESE CATHOLIC RELIGIOUS ARCHITECTURE OF GOA (INDIA) Joaquim Rodrigues dos Santos1 ARTIS – Institute of Art History, School of Arts and Humanities, University of Lisbon https://doi.org/10.30618/978-989-658-467-2_24 ABSTRACT The Goan Catholic religious architecture is undoubtedly a unique and valuable transcultural heritage, which needs to be understood and preserved. For four and a half centuries, during the Portuguese administration, this heritage was conserved following Western premises, moderat- ed by the local influences. With the integration of Goa into India, the preservation became un- der the Indian cultural influence, and this fact has brought some changes. Therefore, issues and idiosyncrasies concerning transculturality, the meaning of heritage and authenticity among dif- ferent cultures (in this case, Portuguese culture and Indian cultures) will be discussed, including the debate on the heritage preservation in Goa. KEYWORDS Goa; Indo-Portuguese architecture; Catholic churches; Heritage Preservation Initial notes Goa is an Indian state that was under Portuguese rule from 1510 until 1961. The initial ter- ritory under Portuguese control was small, but new lands came under Portuguese rule by the second half of the 18th century, thus tripling the Goan territory. The initial territories, con- quered in the 16th century were called Velhas Conquistas (Old Conquests) and the new ones Novas Conquistas (New Conquests). -

Seventeenth-Century Mercantilism and the Age of Liberalism

A Dissertation Entitled Paradigm and Praxis: Seventeenth-Century Mercantilism and the Age of Liberalism By Jeffery L. Irvin, Jr. Submitted as partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Philosophy in History Dr. Glenn J. Ames, Advisor College of Graduate Studies The University of Toledo December 2008 Copyright © 2008 This document is copyrighted material. Under copyright law, no parts of this document may be reproduced without the expressed permission of the author. An Abstract of Paradigm and Praxis: Seventeenth-Century Mercantilism and the Age of Liberalism Jeffery L. Irvin, Jr. Submitted as partial fulfillment of the requirements for The Doctor of Philsophy degree in History The University of Toledo December 2008 At the end of the seventeenth century Western Europe, and perhaps the whole world, had experienced a ‘general crisis’ within the economy. It is the purpose of this dissertation to analyze the responses of England and Portugal with respect to these changes. Within the conceptual framework of the world-capitalist system, which arguably began in the sixteenth century with European expansion, we can see that not all were able to respond effectively to the changes that were taking place. While Portugal had dominated for nearly a century the trade between Asia and Europe that position of dominance was quickly eroded as a result of Spanish domination from 1580 through 1640, the virtual destruction of its navy, and most importantly—as this dissertation will argue—the continued adherence to a socio-political and intellectual perspective that would not meet the challenges of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. England, on iii the other hand, would develop a thoroughly secular perspective of the world which was made possible by the full acceptance of humanist scholarship, the break with the Roman Catholic Church, the alternative to canon law in the form of common law, and the development of a premier naval force that would allow them to dominate trade around the world. -

Parts of Asia

Power, Religion and Violence in Sixteenth-Century Goa 1 Angela Barreto Xavier Abstract: This study seeks to discuss some aspects of the processes of Christianisation in the context of the Portuguese imperial experience in India. The object is a violent event that took place on the outskirts of the region of Salcete (in the villages of Cuncolim, Veroda, Assolna, Velim and Ambelim), situated south of the city of Goa, in 1583. The episode resulted in the deaths of five Jesuits and several Christians, as well as of the villagers who were later held to be responsible for these killings. This incident will be analysed here not just in terms of the metropole-colony relationship (which was becoming increasingly evident after the re-incorporation of these territories in 1543, three decades after the conquest of the city of Goa by Afonso de Albuquerque) but also in the context of the local political, social and religious configurations. This study seeks to discuss some aspects of the processes of Christianisation in the context of the Portuguese imperial experience in India, namely its impact on the expectations and everyday life of local inhabitants. The object of this analysis is a violent event that took place on the outskirts of the region of Salcete (in the villages of Cuncolim, Veroda, Assolna, Velim and Ambelim), situated south of the city of Goa. The episode resulted in the deaths of five Jesuits and several Christians, as well as of the villagers who were later held to be responsible for these killings. This incident will be analysed here not just in Poruguese Literary & Cultural Studies 17/18 (2010): 27-49.