DOE Ela ADD DETEDNEE OM (20 - '1103'11

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

List of Representation /Objection Received Till 31St Aug 2020 W.R.T. Thomas & Araujo Committee Sr.No Taluka Village Name of Applicant Address Contact No

List of Representation /Objection Received till 31st Aug 2020 w.r.t. Thomas & Araujo committee Sr.No Taluka Village Name of Applicant Address Contact No. Sy.No. Penha de Leflor, H.no 223/7. BB Borkar Road Alto 1 Bardez Leo Remedios Mendes 9822121352 181/5 Franca Porvorim, Bardez Goa Penha de next to utkarsh housing society, Penha 2 Bardez Marianella Saldanha 9823422848 118/4 Franca de Franca, Bardez Goa Penha de 3 Bardez Damodar Mono Naik H.No. 222 Penha de France, Bardez Goa 7821965565 151/1 Franca Penha de 4 Bardez Damodar Mono Naik H.No. 222 Penha de France, Bardez Goa nill 151/93 Franca Penha de H.No. 583/10, Baman Wada, Penha De 5 Bardez Ujwala Bhimsen Khumbhar 7020063549 151/5 Franca France Brittona Mapusa Goa Penha de 6 Bardez Mumtaz Bi Maniyar Haliwada penha de franca 8007453503 114/7 Franca Penha de 7 Bardez Shobha M. Madiwalar Penha de France Bardez 9823632916 135/4-B Franca Penha de H.No. 377, Virlosa Wada Brittona Penha 8 Bardez Mohan Ramchandra Halarnkar 9822025376 40/3 Franca de Franca Bardez Goa Penha de Mr. Raju Lalsingh Rathod & Mrs. Rukma r/o T. H. No. 3, Halli Wado, penha de 9 Bardez 9765830867 135/4 Franca Raju Rathod franca, Bardez Goa Penha de H.No. 236/20, Ward III, Haliwada, penha 8806789466/ 10 Bardez Mahboobsab Saudagar 134/1 Franca de franca Britona, Bardez Goa 9158034313 Penha de Mr. Raju Lalsingh Rathod & Mrs. Rukma r/o T. H. No. 3, Halli Wado, penha de 11 Bardez 9765830867 135/3, & 135/4 Franca Raju Rathod franca, Bardez Goa Penha de H.No. -

If Goa Is Your Land, Which Are Your Stories? Narrating the Village, Narrating Home*

If Goa is your land, which are your stories? Narrating the Village, Narrating Home* Cielo Griselda Festinoa Abstract Goa, India, is a multicultural community with a broad archive of literary narratives in Konkani, Marathi, English and Portuguese. While Konkani in its Devanagari version, and not in the Roman script, has been Goa’s official language since 1987, there are many other narratives in Marathi, the neighbor state of Maharashtra, in Portuguese, legacy of the Portuguese presence in Goa since 1510 to 1961, and English, result of the British colonization of India until 1947. This situation already reveals that there is a relationship among these languages and cultures that at times is highly conflictive at a political, cultural and historical level. In turn, they are not separate units but are profoundly interrelated in the sense that histories told in one language are complemented or contested when narrated in the other languages of Goa. One way to relate them in a meaningful dialogue is through a common metaphor that, at one level, will help us expand our knowledge of the points in common and cultural and * This paper was carried out as part of literary differences among them all. In this article, the common the FAPESP thematic metaphor to better visualize the complex literary tradition from project "Pensando Goa" (proc. 2014/15657-8). The Goa will be that of the village since it is central to the social opinions, hypotheses structure not only of Goa but of India. Therefore, it is always and conclusions or recommendations present in the many Goan literary narratives in the different expressed herein are languages though from perspectives that both complement my sole responsibility and do not necessarily and contradict each other. -

GOA UNIVERSITY Taleigao Plateau - Goa List of Rankers for the 31St Annual Convocation Gende Sr

GOA UNIVERSITY Taleigao Plateau - Goa List of Rankers for the 31st Annual Convocation Gende Sr. No. Degree / Exam Seat No. PR. NO. Name of Students Year of Exam CGPA/CPI Marks Perc Class /Grade Add 1 Ph. No. r FLAT NO 4 KAPIL BUILDING HOUSING BOARD COLONY 1 M.A. English EG-1316 201303249 F DO REGO MARIA DAZZLE SAVIA April, 2018 8.60 1496/2000 74.80 A FIRST 9881101875 GHANESHPURI MAPUSA BARDEZ GOA. 403507 HNO.1650 VASVADDO BENAULIM SALCETTE GOA. 2 EG-0116 201302243 F AFONSO VALENCIA SHAMIN April, 2018 8.49 1518/2000 75.90 A SECOND 8322770494 403716 3 EG-4316 201609485 M RODRIGUES AARON SAVIO April, 2018 8.23 1432/2000 71.60 A THIRD DONA PAULA, GOA. 403004 9763110945 1196/A DOMUS AUREA NEOVADDO GOGOL FATORDA 4 M.A. Portuguese PR-0216 201606566 M COTTA FRANZ SCHUBERT AGNELO DE MIRANDA April, 2018 9.29 1643/2000 82.15 A+ FIRST 8322759285 MARGAO GOA. 403602 HOUSE NO. 1403 DANGVADDO BENAULIM SALCETE 5 PR-0616 201606570 F VAS SANDRA CARMEN April, 2018 8.25 1465/2000 73.25 A SECOND 9049558659 GOA. 403716 F1 F2 SANTA CATARIA RESIDENCY SERAULIM SALCETE 6 PR-0316 201302493 F DE SCC REBELO NADIA MARIA DE JESUS April, 2018 7.58 1303/2000 65.15 B+ THIRD 8322789027 GOA. 403708 B-10 ADELVIN APTS SHETYEWADO DULER MAPUSA 7 M.A. Hindi HN-3216 201303177 F VERLEKAR MAMATA DEEPAK April, 2018 8.34 1460/2000 73.00 A FIRST 9226193838 BARDEZ GOA. 403507 H. NO. GUJRA BHAT TALALIM CURCA TISWADI GOA. 8 HN-1416 201307749 F MENKA KUMARI April, 2018 7.50 1281/2000 64.05 B+ SECOND 9763358712 403108 9 HN-3016 201303949 M VARAK DEEPAK PRABHAKAR April, 2018 7.36 1292/2000 64.60 B+ THIRD VALKINI COLONY NO. -

Bastos, C., 2008. from India to Brazil, with a Microscope and a Seat in Parliament

From India to Brazil, with a microscope and a seat in Parliament: the life and work of Dr. Indalêncio Froilano de Melo1 By Cristiana Bastos Indalêncio Froilano de Melo was born in Benaulin, Goa, on the 17th of May 1887. His was a traditional family of Brahmin, Catholic, and landed local aristocrats of the pro- vince of Salcete. Like many other Goan families, they had been Catholics for centuries, had Portuguese names and were at ease with official hierarchies; at the same time, they ranked highly in a social structure that still acknowledged caste status. Moreover, Indalêncio’s father, Constâncio Fran- cisco de Melo, was a lawyer, while his mother, Delfina 1 The on-going analysis included in this article is part of the project Empire, centers and provinces: the circulation of medical knowledge (FCT PTDC/HCT/72143/2006) and benefits from earlier research conducted within the scope of the project Medicina Colonial, Estruturas do Império e Vidas Pós-coloniais em Português (POCTI/41075/ANT/ 2001), both funded by Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia and hosted by the Institute of Social Sciences, University of Lisbon. Institute of Social Sciences, University of Lisbon ([email protected]). HoST, 2008, 2: 139-189 HoST , Vol.1, Summer 2007 Rodrigues, came from a distinguished family; her father, Raimundo Venancio Rodrigues, from the Goan province of Bardez, had been a member of the Portuguese Cortes (Par- liament) and mayor of the city of Coimbra.2 The picture of prosperity changed with the early death of Constâncio de Melo. Young Indalêncio was 12 years old at the time, and from then on he had to work hard on many fronts. -

Global Nomads: Techno and New Age As Transnational Countercultures

1111 2 Global Nomads 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 1011 1 2 A uniquely ‘nomadic ethnography,’ Global Nomads is the first in-depth treat- 3111 ment of a counterculture flourishing in the global gulf stream of new electronic 4 and spiritual developments. D’Andrea’s is an insightful study of expressive indi- vidualism manifested in and through key cosmopolitan sites. This book is an 5 invaluable contribution to the anthropology/sociology of contemporary culture, 6 and presents required reading for students and scholars of new spiritualities, 7 techno-dance culture and globalization. 8 Graham St John, Research Fellow, 9 School of American Research, New Mexico 20111 1 D'Andrea breaks new ground in the scholarship on both globalization and the shaping of subjectivities. And he does so spectacularly, both through his focus 2 on neomadic cultures and a novel theorization. This is a deeply erudite book 3 and it is a lot of fun. 4 Saskia Sassen, Ralph Lewis Professor of Sociology 5 at the University of Chicago, and Centennial Visiting Professor 6 at the London School of Economics. 7 8 Global Nomads is a unique introduction to the globalization of countercultures, 9 a topic largely unknown in and outside academia. Anthony D’Andrea examines 30111 the social life of mobile expatriates who live within a global circuit of counter- 1 cultural practice in paradoxical paradises. 2 Based on nomadic fieldwork across Spain and India, the study analyzes how and why these post-metropolitan subjects reject the homeland to shape an alternative 3 lifestyle. They become artists, therapists, exotic traders and bohemian workers seek- 4 ing to integrate labor, mobility and spirituality within a cosmopolitan culture of 35 expressive individualism. -

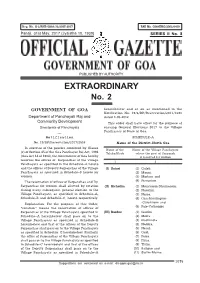

Sr. II N O. 8 Ext. 2.Pmd

Reg. No. G-2/RNP/GOA/32/2015-2017 RNI No. GOAENG/2002/6410 Panaji, 31st May, 2017 (Jyaistha 10, 1939) SERIES II No. 8 PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY EXTRAORDINARY No. 2 GOVERNMENT OF GOA hereinbelow and so on as mentioned in the Notification No. 19/6/DP/Reservation/2011/1698 Department of Panchayati Raj and dated 8-05-2012. Community Development This order shall have effect for the purpose of Directorate of Panchayats ensuing General Elections 2017 to the Village __ Panchayats of State of Goa. Notification SCHEDULE–A No. 19/DP/Reservation/2017/2558 Name of the District–North Goa In exercise of the powers conferred by Clause Name of the Name of the Village Panchayats (c) of Section 45 of the Goa Panchayat Raj Act, 1994 Taluka/Block where the post of Sarpanch (Goa Act 14 of 1994), the Government of Goa hereby is reserved for women reserves the offices of Sarpanchas of the Village 12 Panchayats as specified in the Schedule–A hereto and the offices of Deputy Sarpanchas of the Village (I) Satari (1) Guleli. Panchayats as specified in Schedule–B hereto for (2) Mauxi. women. (3) Morlem and The reservation of offices of Sarpanchas and Dy. (4) Pissurlem. Sarpanchas for women shall allotted by rotation (II) Bicholim (1) Mencurem-Dhumacem. during every subsequent general election to the (2) Navelim. Village Panchayats, as specified in Schedule–A, (3) Naroa. Schedule–B and Schedule–C, hereto respectively. (4) Ona-Maulingem- -Curchirem and Explanation: For the purpose of this Order, (5) Pale-Cothombi. “rotation” means the reservation of offices of Sarpanchas of the Village Panchayats specified in (III) Bardez (1) Guirim. -

Year 2010 Form No

YEAR 2010 FORM NO. 13 FORM OF LIST OF REGISTERED PRACTITIONERS UNDER GOA MEDICAL COUNCIL Sr. No NAME Qualification/Univ. / Regn. No. Schedule Date of Sex Address Year & Date Birth 2725 Dr. Sharma Arun kumar MBBS(Goa) 2009 2725 Goa 05/08/1978 Male Opp. Industrial Area, Ramawatar 22-Jan-10 Jaipur Road, Sikar (Raj) 2726 Dr. Kamate Vishal MBBS(RGUHS)2001 2726 Goa 25/01/1979 Male H.No.58, II Cross, Raghunath MS(OBG)(Goa)2008 25-Jan-10 Mahadwar Road, Belgaum, Karnataka 2727 Dr. Joshi Rajashree Anant MBBS(MUHS)(Nashik) 2727 Goa 13/07/1980 Female H.No.15, Bimbal, Khatode, 2020 2003 29-Jan-10 Valpoi Sattari, Goa 403 506. DMRE(CPS)(Bom)2007 Ph: 9404755670 2728 Dr. Costa Sharon MD(Physician) 2728 Goa 04/12/1980 Female H.No.38A, Oilem - Mou, 2020 Tver State Medical 15-Feb-10 Nr. Two Cross, St. Jose de Academy, Russian Areal, Salcete Goa, 403709. Federation, 2007 Ph: 9769346544 [email protected] 2729 Dr. Pal Shradha Gajanan MBBS(Goa) 2010 2729 Goa 27/07/1987 Female B-45, Journalist Colony, 2020 MD (OBG) (Goa) 23-Mar-10 Behind Bank of Maharashtra May, 2013 10/07/2013 Alto - Porvorim Goa. Ph: 9545762737 [email protected] 2730 Dr. Pednekar Amey Anil MBBS(Goa) 2010 2730 Goa 30/10/1986 Male E-45, Hsg. Board Colony, 2020 MS (General Surgery) 23/03/2010 Mapusa Goa, 403507. (Goa) May, 2013 11/07/2013 Ph:8605286919 [email protected] 2731 Dr. Sadekar Vilas Narayan MBBS(Goa) 2010 2731 Goa 07/01/1987 Male Behind Syndicate Bank, 2020 MS (Orthopaedics) 23/03/2010 Gokulwadi Sanquelim, (Goa) May,2013 22/08/2014 Goa - 403 505 Ph: 9823664880 [email protected] 2732 Dr. -

List of Recognised Educational Institutions in Goa 2010

GOVERNMENT OF GOA LIST OF RECOGNISED EDUCATIONAL INSTITUTIONS IN GOA 2010 - 2011 AS ON 30-09-2010 DIRECTORATE OF EDUCATION STATISTICS SECTION GOVERNMENT OF GOA PANAJI – GOA Tel: 0832 2221516/2221508 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.education.goa.gov.in GOVERNMENT OF GOA LIST OF RECOGNISED EDUCATIONAL INSTITUTIONS IN GOA 2010 - 2011 AS ON 30-09-2010 DIRECTORATE OF EDUCATION STATISTICS SECTION GOVERNMENT OF GOA PANAJI – GOA Tel: 0832 2221516/2221508 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.education.goa.gov.in C O N T E N T Sr. No. Page No. 1. Affiliated Colleges and Recognized Institutions in Goa [Non- Professional] … … … 1 2. Affiliated Colleges and Recognized Institutions in Goa [Professional] … … … … 5 3. Institutions for Professional/Technical Education in Goa [Post Matric Level] … … … 8 4. Institutions for Professional/Technical/Other Education in Goa [School Level]… … … 13 5. Higher Secondary Schools: Government and Government Aided & Unaided … … … 14 6. Government Aided & Unaided High Schools [North Goa District] … … … … … 22 7. Government Aided & Unaided High Schools [South Goa District] … … … … … 31 8. Government Aided & Unaided Middle Schools [North Goa District] … … … … 37 9. Government Aided & Unaided Middle Schools [South Goa District] … … … … 38 10. Government Aided & Unaided Primary Schools [North Goa District] … … … … 39 11. Government Aided & Unaided Primary Schools [South Goa District] … … … … 48 12. Government High Schools (Central and State) … … … … … … … … 56 13. Government Middle Schools [North & South Goa Districts] … … … … … … 60 14. Government Primary Schools [North Goa District] … … … … … … … 63 15. Government Primary Schools [South Goa District] … … … … … … … 87 16. Special Schools … … … … … … … … … … … … … 103 17. National Open Schools … … … … … … … … … … … … 104 AFFILIATED COLLEGES AND RECOGNISED INSTITUTIONS IN GOA [NON – PROFESSIONAL] Sr. -

The Goa Land Development and Building Construction Regulations, 2010

– 1 – GOVERNMENT OF GOA The Goa Land Development and Building Construction Regulations, 2010 – 2 – Edition: January 2017 Government of Goa Price Rs. 200.00 Published by the Finance Department, Finance (Debt) Management Division Secretariat, Porvorim. Printed by the Govt. Ptg. Press, Government of Goa, Mahatma Gandhi Road, Panaji-Goa – 403 001. Email : [email protected] Tel. No. : 91832 2426491 Fax : 91832 2436837 – 1 – Department of Town & Country Planning _____ Notification 21/1/TCP/10/Pt File/3256 Whereas the draft Regulations proposed to be made under sub-section (1) and (2) of section 4 of the Goa (Regulation of Land Development and Building Construction) Act, 2008 (Goa Act 6 of 2008) hereinafter referred to as “the said Act”, were pre-published as required by section 5 of the said Act, in the Official Gazette Series I, No. 20 dated 14-8- 2008 vide Notification No. 21/1/TCP/08/Pt. File/3015 dated 8-8-2008, inviting objections and suggestions from the public on the said draft Regulations, before the expiry of a period of 30 days from the date of publication of the said Notification in the said Act, so that the same could be taken into consideration at the time of finalization of the draft Regulations; And Whereas the Government appointed a Steering Committee as required by sub-section (1) of section 6 of the said Act; vide Notification No. 21/08/TCP/SC/3841 dated 15-10-2008, published in the Official Gazette, Series II No. 30 dated 23-10-2008; And Whereas the Steering Committee appointed a Sub-Committee as required by sub-section (2) of section 6 of the said Act on 14-10-2009; And Whereas vide Notification No. -

Chapter Twelve Jesuit Schools and Missions in The

CHAPTER TWELVE JESUIT SCHOOLS AND MISSIONS IN THE ORIENT 1 MARIA DE DEUS MANSO AND LEONOR DIAZ DE SEABRA View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Missions in India brought to you by CORE provided by Repositório Científico da Universidade de Évora The Northern Province: Goa 2 On 27 th February 1540, the Papal Bull Regimini Militantis Eclesiae established the official institution of The Society of Jesus, centred on Ignacio de Loyola. Its creation marked the beginning of a new Order that would accomplish its apostolic mission through education and evangelisation. The Society’s first apostolic activity was in service of the Portuguese Crown. Thus, Jesuits became involved within the missionary structure of the Portuguese Patronage and ended up preaching massively across non-European spaces and societies. Jesuits achieved one of the greatest polarizations and novelties of their charisma and religious order precisely in those ultramarine lands obtained by Iberian conquest and treatises 3. Among other places, Jesuits were active in Brazil, India, Indonesia, Malaysia, Japan and China. Their work gave birth to a new concept of mission, one which, underlying the Society’s original evangelic impulses, started to be organised around a dynamic conception of “spiritual conquest” aimed at converting to the Roman Catholic faith all those who “simply” ignored or had strayed from Church doctrines. In India, Jesuits created the Northern (Goa) and the Southern (Malabar) Provinces. One of their characteristics was the construction of buildings, which served as the Mission’s headquarters and where teaching was carried out. Even though we have a new concept of college nowadays, this was not a place for schooling or training, but a place whose function was broader than the one we attribute today. -

Presentación De Powerpoint

Wonderful Goa - Golden sun, white sands and local cuisines The programme Come to Goa to unwind on its white sand beaches, simply relax and soak in the sun while tasting some bites of the delicious Goan cuisine and seafood. Don’t miss Old Goa with its stunning cathedrals and architecture that witness the glorious Portuguese past of Goa. The Experiences Explore the white sand beaches of Goa Enjoy water sports like boating, parasailing, banana rides and Jet Ski Explore the famous nightclubs of Goa Visit Dudhsagar waterfalls Tour the churches of Goa Discover Loutolim, an old town where Hindus and Christians live in harmony Visit the flea markets of Goa Wonderful Goa - Golden sun, white sands and local cuisines The Experiences | Day 01: Arrive Goa Welcome to India! On arrival at Goa Airport, you will be greeted by our tour representative in the arrival hall, who will escort you to your hotel and assist you in check-in. Kick off your holiday unwinding on the golden sand beaches of Goa. Laze around at Calangute Beach and Candolim Beach and enjoy the delightful Goan cuisine. Goa is famous for its seafood, including deliciously cooked crabs, prawns, squids, lobsters and oysters. The influence of Portuguese on Indian cuisine can best be explored here. As an ex-colony, Goa still retains Portuguese influences even today. Soak up the sunset panorama at Baga Beach - a crowded beach that comes to life at twilight. Spend a few hours by candle light and enjoy drinks and dinner with the sound of gushing waves in the background. -

Agenda 15-06-2016

CORRESPONDENCE TO BE PLACED BEFORE FORTHNIGHTLY MEETING TO BE HELD ON 15/06/2016. Sr. Name of Applicant/Dept. Subject Matter Remarks No. 2.CONSTRUCTIONS PLANS FOR GRANT OF CONSTRUCTION LICENCE.(File No.100) 1. Somenath Mahanty & Construction of residential Aparna Mahanty Flat building & boundary wall in No. TF-2 Rosemin land bearing Sy. No. 175/1-G, Arcade Aquem Margao Plot No. 9, at Moddi. 2. Somenath Mahanty & Construction of residential Aparna Mahanty Flat building & boundary wall in No. TF-2 Rosemin land bearing Sy. No. 175/1-G, Arcade Aquem Margao Plot No. 8, at Moddi. 3. Simon F. Fernandes Construction of residential H.no.730 Fradilem building & Boundary wall in land bearing Sy.No.169/8-A, at Fradilem. 4. Reliance Jio Infocomm Permission for setting up Limited., 9th floor, wireless Broadband Network Maker Chambers IV, for 4G Services in 222, Nariman Point, H.No.842/3(1) & 842/3(2) at Mumbai- 400021. Mandopa. 5. Nina Fatima Gomes Const of comp wall & twin C/O Rene Xavier Bungalows in Sy.No.190/5-A- Gomes 149/A Opp 4 at Moddi. Carmelite Monastery Malbhat Margao 3(1) OCCUPANCY CERTIFICATE.(File No.101) 1. Marianinha Barreto Issue of occupancy Certificate Ratwaddo Navelim for proposed construction of multi dwelling unit (Towards southern side) in Sy.No.88/1- C at Ratvaddo. 2. Prabhudessai realtors Issue of occupancy Certificate Pajifond Margao Goa for proposed construction of Block A & B Building in Sy.No.103/2 at Nagmodem. 3(2)REGARDING TRANSFER OF HOUSE TAX.(File No.58) 1. Maria Alda S.