JET LAG Keith Ross Miller, 1948 Michael Parkinson

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Turn Down Collar, Punter ATTHE'

Herald Sun Friday 7/8/2009 Brief: HAIR(M) Page: 81 Section: Sport Region: Melbourne Circulation: 518,000 Type: Capital City Daily Size: 135.82 sq.cms. Frequency: MTWTFS- Turn down collar, Punter ATTHE'. ' BAR i JA: I was told you were seen has Ricky Pouting been better shot selection. them out. drinkingwith Kevin Pietersencopping over there? Totonight,please tell me we You aren't worried about the during the third Test. You have to be here to believecan win. form of Siddle or Johnson? RH: Met him in a sponsor's it. The Barmy Army doesn't England will win the series 1-0.The latter's arm has been tent. Not a bad bloke. stop on him and that clown Given your appalling tipping getting very low in England, to That's interesting given a with the trumpet was waitingrecord,I now knowwe can win.the point where it wouldn't week ago you referred to him for the team bus when it The track for the last Test at shock me to see him do a as an ego-maniac. arrived in Headingley, blowingThe Oval will be a road so thisTrevor Chappell. That was before I met him. Heit in his face when he got off. is our only chance. He was OK at Edgbaston. We knew who I was so that lifted There is something about Why wouldn't England just need Siddle aggressive and him from 2 out of 10 to 8 out ofPonting, a lack of humour, a stack its side with batting andLee has a new hair hat so will 10. -

The Fountain

The Fountain Wednesday 22 July 2020 On This Day The Way We Were bit.ly/2QKHMmK bit.ly/2UIuD0Z Prince George Strawberry jelly and ice cream George Alexander Louis Why do people seem to think Windsor was born on 22nd that jelly and ice cream is July 2013. He is the eldest only for children’s birthday child of the Duke and Duchess parties? I thought it was one of Cambridge, and is third in of the most refreshing desserts line to the throne. for a summer meal. It went Kate Middleton married well with fruit salad too. Prince William in 2011. It Jelly is easy enough to make. was a joyful royal wedding. I used to make the jelly first The couple were given the thing in the morning when I titles of Duke and Duchess of boiled the kettle for a cup of Cambridge. Two years later, tea. I usually used Rowntrees along came baby George. or Chivers jelly cubes. As soon One day he will have the as it was cool I popped it into heavy responsibility of being the fridge to set. king. But for now he can just We usually had a tub of ice enjoy school and growing up. cream in the freezer, so I didn’t We hope he has a wonderful need to do any preparation – seventh birthday. just serve it up for ‘afters’. Copyright © 2020 Everyday Miracles Ltd T/A The Daily Sparkle ® www.dailysparkle.co.uk 22 July 2020 1 That’s Life Over To You bbc.in/31KXmDM bit.ly/1i9NH0R Keith Miller Twins When I was a boy, I followed Dear Mary and Jimmy cricket avidly. -

CRICKET - AUSTRALIA - 1928-1948 - the Bradman Era

Page:1 Nov 25, 2018 Lot Type Grading Description Est $A CRICKET - AUSTRALIA - 1928-1948 - The Bradman Era Lot 2072 2072 1930 Victor Richardson's Ashes Medal sterling silver with Australian Coat-of-Arms & 'AUSTRALIAN ELEVEN 1930' on front; on reverse 'Presented to the Members of the Australian Eleven in Commemoration of the Recovery of The Ashes 1930, by General Motors Australia Pty Limited', engraved below 'VY Richardson', in original presentation case. [Victor Richardson played 19 Tests between 1927-36, including five as Australian captain; he is the grandfather of Ian, Greg & Trevor Chappell] 3,000 Lot 2073 2073 1934 Australian Team mounted photograph signed by the entire squad (19) including Don Bradman, Bill Woodfull, Clarrie Grimmett & Bill Ponsford, framed & glazed, overall 52x42cm. 1,500 Page:2 www.abacusauctions.com.au Nov 25, 2018 CRICKET - AUSTRALIA - 1928-1948 - The Bradman Era (continued) Lot Type Grading Description Est $A Lot 2074 2074 1934 'In Quest of the Ashes 1934 - The Don Bradman Souvenir Booklet and Scoring Records', published by Wrigleys, with the scarce scoring sheet, and also a letter from Wrigleys to the previous owner, explaining he needed to send 30 wrappers before they would despatch the Cricket Book. 200 Lot 2075 2075 1935-36 Australian Team photograph from South African Tour with 16 signatures including Victor Richardson, Stan McCabe, Bert Oldfield & Bill O'Reilly, overall 39x34cm, couple of spots on photo & some soiling, signatures quite legible. [Australia won the five-Test series 4-0] 400 2076 1936 'The Ashes 1936-1937 - The Wrigley Souvenir Book and Scoring Records', published by Wrigley's, with the scarce scoring sheet completed by the previous owner, front cover shows the two opposing captains Don Bradman & Gubby Allen, some faults. -

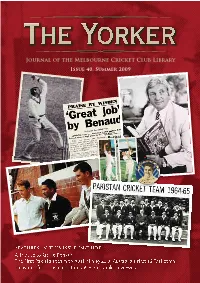

Issue 40: Summer 2009/10

Journal of the Melbourne Cricket Club Library Issue 40, Summer 2009 This Issue From our Summer 2009/10 edition Ken Williams looks at the fi rst Pakistan tour of Australia, 45 years ago. We also pay tribute to Richie Benaud's role in cricket, as he undertakes his last Test series of ball-by-ball commentary and wish him luck in his future endeavours in the cricket media. Ross Perry presents an analysis of Australia's fi rst 16-Test winning streak from October 1999 to March 2001. A future issue of The Yorker will cover their second run of 16 Test victories. We note that part two of Trevor Ruddell's article detailing the development of the rules of Australian football has been delayed until our next issue, which is due around Easter 2010. THE EDITORS Treasures from the Collections The day Don Bradman met his match in Frank Thorn On Saturday, February 25, 1939 a large crowd gathered in the Melbourne District competition throughout the at the Adelaide Oval for the second day’s play in the fi nal 1930s, during which time he captured 266 wickets at 20.20. Sheffi eld Shield match of the season, between South Despite his impressive club record, he played only seven Australia and Victoria. The fans came more in anticipation games for Victoria, in which he captured 24 wickets at an of witnessing the setting of a world record than in support average of 26.83. Remarkably, the two matches in which of the home side, which began the game one point ahead he dismissed Bradman were his only Shield appearances, of its opponent on the Shield table. -

249 - November 2004

THE HAMPSHIRE CRICKET SOCIETY Patrons: John Woodcock Frank Bailey Colin lngleby-Mackenzie NEWSLETTER No. 249 - NOVEMBER 2004 KEITH MIILLER TRIBUTE Keith Miller, who died in October, was one of the game's immortals. The obituaries in the broadsheets and on the cricinfo. website paid fulsome tribute to his qualities both as a cricketer and a man, and it is not proposed to go through his career in any detail in this piece. However, he was indisputably the finest all-rounder in Australian cricket history and only ever bettered by Sir Garfield Sobers, and arguably Imran Khan. The true indicator of an all-rounder's quality is the differential between their batting and bowling averages. Of those who played for any time in Test cricket, Sobers (+23.75), Miller (+ 14) and Imran Khan (+14.88) stand head and shoulders above all others. Unlike the other two mentioned above, Keith Miller never captained his country in Test matches. He upset Sir Donald Bradman on a number of occasions early on in his career and was never forgiven. And yet no less a judge than Richie Benaud rated Miller as the best captain he ever played under. As with everywhere else he played, KEITH ROSS MILLER left an indelible mark on the Hampshire cricketing public, perhaps never more so than on his very first appearance on a Hampshire ground. Through the pen of John Arlott and the story telling of that incomparable raconteur, Arthur Holt, that event has passed into the County's folklore. It was during war time, in a charity match at Southampton's Parks. -

Extract Catalogue for Auction

Page:1 May 19, 2019 Lot Type Grading Description Est $A CRICKET - AUSTRALIA 29 AUTOGRAPHS: including Australia ODI shirt signed by Shane Warne; display signed by Don Bradman & Bill Ponsford; cricket bat signed by Greg, Ian & Trevor Chappell; also cricket cards 'Cricketers 1934' {50} & 'Cricketers 1938' {50}. 300 Lot 30 30 - Australian Test Captains autographs on 1992 Sheffield Shield Centenary stamps in gutter pairs, signed by Don Bradman, Richie Benaud, Lindsay Hassett, Ian Johnson, Ian Craig, Greg Chappell, Bill Brown, Brian Booth, Ian Chappell, Arthur Morris, Graham Yallop, Kim Hughes, Neil Harvey, Bill Lawry, Barry Jarman, Bob Simpson & Mark Taylor. 300 Ex Lot 31 31 BADGES: 1930-48 Circular 25mm badges 'Australian Cricketers' comprising Bromley, Brown, Chipperfield (2), Darling, Ebeling, Fingleton, Fleetwood-Smith, Grimmett, Kippax, McCabe, McCool, Oldfield, O'Reilly, Ponsford, Waite, Wall, Ward, White & Woodfull; also 21mm badge of Wally Hammond. Mainly Fine/Very Fine. (21) 200 32 BATS: comprising 'Kookaburra' bat signed by Ricky Ponting; two 1940s match-used bats; 'Wisden' & 'Pride of Pakistan' bats. (5) 120 33 - 'County' cricket bat with 14 signatures including Merv Hughes, Doug Walters, Alan Connolly & Darren Berry. Housed in display case (no glass), overall 32x103cm. 100 Page:2 www.abacusauctions.com.au May 19, 2019 CRICKET - AUSTRALIA (continued) Lot Type Grading Description Est $A Lot 34 34 - Cricket bat display with three signed bats - Australia 2004, Sri Lanka 2006 & Victoria 2006 (v Queensland in Pura Cup Final), framed together, overall 64x105cm. 300 35 CLOTHING: Australian Cricket Tie from 1926 International Cricket Convention, green with diagonal gold stripes made by Farmer's of Sydney; plus Darren Lehmann pair of Gray Nicolls batting gloves, from Tasmania v South Australia at Launceston 2001-02 (Lehmann Man of the Match with 85 not out). -

December 2016 Catalogue

ROGER PAGE DEALER IN NEW AND SECOND-HAND CRICKET BOOKS 10 EKARI COURT, YALLAMBIE, VICTORIA, 3085 TELEPHONE: (03) 9435 6332 FAX: (03) 9432 2050 EMAIL: [email protected] ABN 95 007 799 336 DECEMBER 2016 CATALOGUE Unless otherwise stated, all books in good condition & bound in cloth boards. Books once sold cannot be returned or exchanged. G.S.T. of 10% to be added to all listed prices for purchases within Australia. Postage is charged on all orders. For parcels l - 2kgs. in weight, the following rates apply: within Victoria $14:00; to New South Wales & South Australia $16.00; to the Brisbane metropolitan area and to Tasmania $18.00; to other parts of Queensland $22; to Western Australia & the Northern Territory $24.00; to New Zealand $40; and to other overseas countries $50.00. Overseas remittances - bank drafts in Australian currency - should be made payable at the Commonwealth Bank, Greensborough, Victoria, 3088. Mastercard and Visa accepted. This List is a selection of current stock. Enquiries for other items are welcome. Cricket books and collections purchased. A. ANNUALS AND PERIODICALS $ ¢ 1. A.C.S International Cricket Year Books: a. 1986 (lst edition) to 1996 inc. 20.00 ea b. 2014, 2015, 2016 70.00 ea 2. Australian Cricket Annual (ed) Allan Miller: a. 1987-88 (lst edition), 1988-89, 1989-90 40.00 ea b. 1990-91, 1991-92, 1992-93 30.00 ea c. 1996, 1997, 1998, 1999, 2000, 2001 20.00 ea 3. Australian Cricket Digest (ed) Lawrie Colliver: a. 2012-13, 2013-14, 2014-15, 25.00 ea. -

Sample Download

Bent Arms & Dodgy Wickets England’s Troubled Reign as Test Match Kings during the Fifties By Tim Quelch Pitch Publishing Ltd A2 Yeoman Gate Yeoman Way Durrington BN13 3QZ Email: [email protected] Web: www.pitchpublishing.co.uk First published in the UK by Pitch Publishing, 2012 Text © 2012 Tim Quelch Tim Quelch has asserted his rights in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 to be identified as the author of this work. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission in writing of the publisher and the copyright owners, or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the terms stated here should be sent to the publishers at the UK address printed on this page. The publisher makes no representation, express or implied, with regard to the accuracy of the information contained in this book and cannot accept any legal responsibility for any errors or omissions that may be made. A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. 13-digit ISBN: 978-1908051837 Cover design by Brilliant Orange Creative Services. Typesetting by Liz Short. Printed in Great Britain by TJ International. ‘REELING IN THE YEARS’: AN INTRODUCTION hen Andrew Strauss’s team seized the world Test match number one position in the summer of 2011 they finally recovered what had been lost at the Adelaide Oval in February 1959.W England had previously been top of the world during the mid 1950s. -

Signed Cricket Books All Books Are Hardcover with Dust Wrappers Unless Otherwise Specified

THE ANTIQUE BOOKSHOP & CURIOS Tel: 02 9966 9925 Email:[email protected] eList No.3 - Signed cricket books All books are hardcover with dust wrappers unless otherwise specified. 2 AUSTRALIAN CRICKET BOARD. 1997 1 AUSTRALIAN BOARD OF CONTROL. Ashes Tour. Glass framed, team sheet of the 1953 Coronation Tour. Official autographed Australian touring party. Signed by 17 players team sheet. Signed by all 17 members of the including Mark Taylor, Steve Waugh, Glenn touring party in ink ballpoint, including Lindsay McGrath, Shane Warne and Ricky Ponting. Plus Hassett, Arthur Morris, Ray Lindwall, Neil five others, including coach Jeff Marsh. 21cm x Harvey, Keith Miller and Richie Benaud. $120 29cm. $100 THE ANTIQUE BOOKSHOP & CURIOS Tel: 02 9966 9925 Email: [email protected] 3 BORDER, Alan. ASHES GLORY. ALAN BORDER’S OWN STORY. Byron Bay. Swan Publishing. 1989. 159pp. With Border signed white slip, 10cm x 7cm. $35. 4 BRIGGS, Simon and others. ENGLAND’S ASHES. THE STORY OF THE GREATEST TEST SERIES OF ALL TIME. London. Harper Collins. 2005. 194pp. Folio with numerous colour illustrations of the 7 GAVASKAR, Sunil. IDOLS. London. famous 2005 test series in Allen and Unwin. 1984. 289pp. Signed by the England. With signatures famous Indian batsman on the title page, “good of English players, Paul wishes, Sunil Gavaskar, 1984”. Gavaskar covers Collingwood, Mike Gatting, Ian Bell, Marcus the famous players that he has met in his career. Tresc othick, Matthew Hoggard, Ashley Giles, Protective d/w. $55 Geraint Jones and Simon Jones on white cards. Simon Jones on the back of a black and white 8 GREIG, Tony. -

Sonny Ramadhin and the 1950S World of Spin, 1950-1961

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Publications and Research College of Staten Island 2004 Sonny Ramadhin and the 1950s World of Spin, 1950-1961 David M. Traboulay CUNY College of Staten Island How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/si_pubs/80 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] SONNY RAMADHIN AND THE 1950S WORLD OF SPIN, 1950-1961, WITH AN EPILOGUE ON THE MODERN FATE OF TRADITIONAL CRICKET DAVID M. TRABOULAY 1 CONTENTS PREFACE 3 CHAPTER 1: LOCATING RAMADHIN AND SAN FERNANDO 5 CHAPTER 2: THE SURPRISING CONQUEST OF ENGLAND, 1950 23 CHAPTER 3: BATTLE FOR WORLD CHAMPION: AUSTRALIA, 1951 45 CHAPTER 4: THE PAST AS PROLOGUE: BUILDING A TRADITION 54 CHAPTER 5: INDIA IN THE CARIBBEAN, 1953 81 CHAPTER 6: PLAYING AT HOME: ENGLAND AND AUSTRALIA, 1954/55 99 CHAPTER 7: VICTORY IN NEW ZEALAND, DEFEAT IN ENGLAND, 1956/57 119 CHAPTER 8: THE EMERGENCE OF PACE: TOWARDS A NEW ORDER 138 CHAPTER 9: THE GREAT 1960/61 TOUR TO AUSTRALIA; FAREWELL 151 CHAPTER 10: HOME AND THE WORLD: LEAGUE CRICKET 166 CHAPTER 11: EPILOGUE:THE FATE OF TRADITIONAL CRICKET 177 2 PREFACE The idea of a study of Ramadhin and cricket in the 1950s arose from the desire to write something about San Fernando, the town where I was born and grew up. Although I have lived in America for more than forty years, San Fernando still occupies a central place in my imagination and is one of the sources of the inspiration of whatever little I have achieved in my life. -

Cricket Museum

NEW ZEALAND CRICKET MUSEUM New Zealand v Australia, Basin Reserve, Wellington, 29, 30 March 1946 New Zealand opening batsmen William (“Mac”) Anderson (left) and Walter Hadlee Photo: Unknown Private Collection Winter/Spring Newsletter 2007 COLLECTION MANAGEMENT Vernon Collection Management System photography and ephemera treasures had The Vernon Collection Management System software and been entered into Vernon by the end of the computer hardware, including a scanner, purchased in late fi nancial year (31 May 2007). The next step 2006, were installed and operational by February 2007. is the planned appointment of a part-time The process of accessioning collection items began in late Collections Assistant in the second half February with assistance from Laureen Sadlier, Collection of 2007. Anna Montgomery Curator, Museum of Wellington City and Sea. EDUCATION Education Groups The target of 25 education group visits was achieved in the 2006/07 fi nancial year. This included primary, intermediate, secondary and tertiary students, as well as Rest Home residents. Outreach Programme The museum outreach programme was extended with a visit to the Waikanae Probus Club and a very successful visit to Upper Hutt for the Annual Sports Awards. A talk to an audience of 150 people resulted in a $600 payment to the museum. Age Group Team Visits David Mealing, Museum Curator, introducing Richard Bourne, Museum Trustee, from Wanganui Collegiate, to the Vernon Collection Three groups of Wellington age group teams are scheduled to Management System, May 2007 visit the museum in August. A programme will be presented Photographer: Paddianne Neely NZCM Archives to u12, u13 and u14 boys, variously organised to give them a perspective on the beginnings of the game, the history and Anna Montgomery, a museum volunteer, has since been development of the game in Wellington and New Zealand, as trained to use Vernon and so advance this vast and long-term well as an insight into some of the great New Zealand cricketers task of professionally cataloguing the collection. -

Club Christmas Luncheon

City Livery Club uniting the livery, promoting fellowship Lord’s: Museum, Long Room & behind-the-scenes tour St John’s Wood Road, London NW8 8QN Tuesday 29 March 2016 5.30p.m. Lord’s Cricket Ground, one of the most prestigious sporting venues owned by the MCC for the past 200 years, is world famous as “the home of cricket” and hosts more games than any other cricket club. President John MacCabe invites you to join him for a private tour, starting in the MCC Museum, home of the famous Ashes urn, which in the view of our President is possibly the most iconic trophy in international sport. A wonderful opportunity to see behind the scenes at one of the most prestigious sporting venues in the world and a true London landmark. The Museum brings the fascinating story of cricket to life. Paintings, photographs and artefacts, covering 400 years of cricket history, reveal the game's development from a rural pastime to a modern, increasingly international sport. Precious exhibits include the Wisden Trophy and the tiny, delicate and irreplaceable Ashes urn. The museum also boasts bats, balls and kit donated by great players including past greats such as WG Grace, Victor Trumper, Jack Hobbs, Keith Miller and Don Bradman. The tour continues through the heart of the Pavilion to the famed Long Room, both a cricket-watching room and a cricket art gallery. The Long Room has a unique atmosphere, panoramic views of the pitch and is where players make their way to and from the 'hallowed turf'. Other highlights include the players' Dressing Rooms with the renowned Lord's Honours Boards, providing a lasting reminder of exceptional batting and bowling performances in Lord's Tests.