The Art Direction Handbook for Film

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Techniques and Practical Skills in Scenery, Set Dressing and Decorating for Live-Action Film and Television

International Specialised Skills Institute Inc Techniques and Practical Skills in Scenery, Set Dressing and Decorating for Live-Action Film and Television Julie Belle Skills Victoria/ISS Institute TAFE Fellowship Fellowship funded by Skills Victoria, Department of Innovation, Industry and Regional Development, Victorian Government ISS Institute Inc. APRIL 2010 © International Specialised Skills Institute ISS Institute Suite 101 685 Burke Road Camberwell Vic AUSTRALIA 3124 Telephone 03 9882 0055 Facsimile 03 9882 9866 Email [email protected] Web www.issinstitute.org.au Published by International Specialised Skills Institute, Melbourne. ISS Institute 101/685 Burke Road Camberwell 3124 AUSTRALIA April 2010 Also extract published on www.issinstitute.org.au © Copyright ISS Institute 2010 This publication is copyright. No part may be reproduced by any process except in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. Whilst this report has been accepted by ISS Institute, ISS Institute cannot provide expert peer review of the report, and except as may be required by law no responsibility can be accepted by ISS Institute for the content of the report, or omissions, typographical, print or photographic errors, or inaccuracies that may occur after publication or otherwise. ISS Institute do not accept responsibility for the consequences of any action taken or omitted to be taken by any person as a consequence of anything contained in, or omitted from, this report. Executive Summary In film and television production, the art department operates, under the leadership of the production designer or art director, to create and manipulate the overall ‘look, feel and mood’ of the production. The appearance of sets and locations transports audiences into the world of the story, and is an essential element in making a production convincing and evocative. -

College Choices for the Visual and Performing Arts 2011-2012

A Complete Guide to College Choices for the Performing and Visual Arts Ed Schoenberg Bellarmine College Preparatory (San Jose, CA) Laura Young UCLA (Los Angeles, CA) Preconference Session Wednesday, June 1 MYTHS AND REALITIES “what can you do with an arts major?” Art School Myths • Lack rigor and/or structure • Do not prepare for career opportunities • No academic challenge • Should be pursued as a hobby, not a profession • Graduates are unemployable outside the arts • Must be famous to be successful • Creates starving artists Copyright: This presentation may not be reproduced without express permission from Ed Schoenberg and Laura Young (June 2016) Art School in the News Visual/Performing Arts majors are the… “Worst-Paid College Majors” – Time “Least Valuable College Majors” – Forbes “Worst College Majors for your Career” – Kiplinger “College Degrees with the Worst Return on Investment” – Salary.com Copyright: This presentation may not be reproduced without express permission from Ed Schoenberg and Laura Young (June 2016) Art School Reality Projected More than 25 28 million in 2013 million in 2020 More than 25 million people are working in arts-related industry. By 2020, this is projected to be more that 28 million – a 15% increase. (U.S. Department of Labor) Copyright: This presentation may not be reproduced without express permission from Ed Schoenberg and Laura Young (June 2016) Art School Reality Due to the importance of creativity in the innovation economy, more people are working in arts than ever before. Copyright: This presentation -

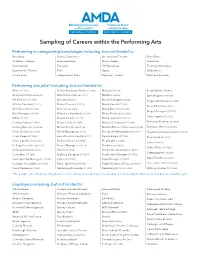

Sampling of Careers Within the Performing Arts

Sampling of Careers within the Performing Arts Performing in categories/places/stages including, but not limited to: Broadway Dance Companies International Theatre Short Films Children’s Theatre Documentaries Music Videos Television Commercials Festivals Off-Broadway Touring Companies Community Theatre Film Opera Web Series Cruise Ships Independent Films Regional Theatre West End London Performing arts jobs* including, but not limited to: Actor (27-2011) Dance Academy Owner (27-2032) Mascot (27-2090) Script Writer (27-3043) Announcer/Host (27-2010) Dance Instructor (25-1121) Model (27-2090) Set Designer (27-1027) Art Director (27-1011) Dancer (27-2031) Music Arranger (27-2041) Singer Songwriter (27-2042) Artistic Director (27-1011) Dialect Coach (25-1121) Music Coach (27-2041) Sound Editor (27-4010) Arts Educator (25-1121) Director (27-2012) Music Director (27-2041) Stage Manager (27-2010) Arts Manager (11-9190) Director’s Assistant (27-2090) Music Producer (27-2012) Talent Agent (27-2012) Ballet (27-2031) Drama Coach (25-1121) Music Teacher (25-1121) Casting Agent (27-2012) Drama Critic (27-3040) Musical Composer (27-2041) Technical Director (27-4010) Casting Director (27-2012) Drama Teacher (25-1121) Musical Theatre Musician (27-2042) Technical Writer (27-3042) Choir Director (27-2040) Event Manager (27-3030) Non-profit Administrator (43-9199) Theatre Company Owner (27-2032) Choir Singer (27-2042) Executive Assistant (43-6011) Opera Singer (27-2042) Tour Guide (39-7011) Choreographer (27-2032) Fashion Model (27-2090) Playwright (27-3043) -

Art/Production Design Department Application Requirements

Art/Production Design Department Thank you for your interest in the Art Department of I.A.T.S.E. Local 212. Please take a few moments to read the following information, which outlines department specific requirements necessary when applying to the Art Department. The different positions within the Art/Production Department include: o Production Designer o Art Director (Head of Department) o Assistant Art Director o Draftsperson/Set Designer o Graphic Artist/Illustrator o Art Department Coordinator and o Trainee Application Requirements For Permittee Status In addition to completing the “Permit Information Package” you must meet the following requirement(s): o A valid Alberta driver’s license, o Have a strong working knowledge of drafting & ability to read drawings, o Have three years professional Design training or work experience, o Strong research abilities, o Freehand drawing ability and o Computer skills in Accounting and/or CADD and or Graphic Computer programs. APPLICANTS ARE STRONGLY RECOMMENDED TO HAVE EXPERIENCE IN ONE OR MORE OF THE FOLLOWING AREAS: o Art Departments in Film, Theatre, and Video Production o Design and Design related fields: o Video/Film and Television Art Direction & Staging o Theatrical Stage Design & Technical Direction o Architectural Design & Technology o Interior Design o Industrial Design o Graphic Design o Other film departments with proven technical skills beneficial to the needs of the Art Department. Your training and experience will help the Head of the Department (HOD) determine which position you are best suited for. Be sure to clearly indicate how you satisfy the above requirements. For example, on your resume provide detailed information about any previous training/experience (list supervisor names, responsibilities etc.) Additionally, please provide copies of any relevant licenses, tickets and/or certificates etc. -

Resume of Kim Bailey “ Feature Projects ”

Local #800 Local #44 Resume of Kim Bailey “ Feature Projects ” ADOD, LLC. 2008-Present, ADOD, LLC. (Artistic Development on Demand) (Los Angeles) C.E.O. Current entrepreneurial venture outside the scope of the entertainment industry. Business model focuses on conceptual business development, development of the brand image along with image consulting, architectural interior design and themed entertainment environments , in-house graphics, development & design of advertisement campaign relating to corporate message and trade show exhibits, product placement, web design, marketing strategies, tools & sales materials, consulting for personnel management of staff, vendors and direction of sales force. Damaged Goods 2012, Serious Damage Productions, LLC. Director: Annie Biggs (Los Angeles - PILOT) Production Designer Hired by: (Executive Producer) Annie Biggs Interfaced with: (All aspects of production) Responsible for complete design and look for all aspects of production. Pranked 2011, Untitled, LLC. Director: Adam Rifkin (Los Angeles) Supervising Art Director Hired by: (Producer) Bernie Gewissler Interfaced with: (Production, Director & Executive Producer) Responsible for complete design and look for all aspects of production. The Wrath of Shatner 2010, Free Enterprise 2, LLC. Director: Robert Burnett (Los Angeles) Supervising Art Director to Production Designer Hired by: (Producer) Jeffrey Cohglan Interfaced with: (Production & Director) Responsible for complete design and look for all aspects of production, took over for Production designer -

Downsizing Presentation 14.Cdr

Istanbul conference High school reunion Int. plane Leisureland shuttle bus Leisureland visitors center Leisureland visitors center Leisureland visitors center Leisureland model home Leisureland model home Leisureland keepsake box Downsizing procedure Downsizing procedure Downsizing procedure Downsizing procedure Downsizing procedure Welcome to Leisureland Welcome to Leisureland Leisureland interiors Leisureland lawyer’s office Leisureland workers housing Bus Leisureland transportation Ext. Alondra apartments Alondra apartments Alondra apartments Alondra apartments Ext. Alondra apartments Norwegian fjord Norwegian village Norwegian village Norwegian village Norwegian village Norwegian village Leisureland concepts Leisureland branding Leisureland branding Production Designer Stefania Cella Supervising Art Director Kimberley Zaharko Art Directors Jørgen Stangebye Larsen Karl J. Martin Doug J. Meerdink Set Decorators Patricia Larman Karen Manthey Construction Accountant Lara Alexander Head Painter Peter Aquilina Model Maker Nick Augustyn Set Dresser Ryan Berkinshaw Art Department Coordinator: Additional Photography Jill Blackledge Set Designer Rudy Braun Assistant Art Director Katie Brock Storyboard Artist Doug Brode Leadman Jon J. Bush Art Advisor Nathan Carlson Set Designer Allen Coulter Specialty Prop Designer/Builder Taku Dazai Lead Painter Richard Ewan Props Buyer Ann-Marie Ferney-Tellez Moldmaker Jonathan Graham Concept Artist Ben Grangereau Set Designer Etienne Gravrand Assistant Property Master David Gruer Property Master David Gulick -

Pact BECTU Feature Film Agreement Grade Ladder PAY GROUP

Pact BECTU Feature Film Agreement Grade Ladder PAY GROUP 12 Armourer 1 All Runners Board Operator Boom Operator 2 Art Dept Junior Chargehand Props Camera Trainee Electrician Costume Trainee Post Prod. Supervisor Directors Assistant Production Buyer Electrical Trainee / junior Rigging Electrician Jnr Costume Asst Senior Make-up Artist Make-up Traineee SFX Technician Producers Assistant Stand-by Art Director Production Secretary Props Trainee / junior 13 1st Asst. Editor Script Supervisor's Assistant Art Director Sound Trainee / junior Convergence Puller DIT 3 2nd Assistant Editor 3rd Assistant Director 14 ?Crane Technician? Accounts Assistant/cashier Grip Art Dept Co-ordinator Location Manager Art Dept Assistant Prop Master Asst Production Co-ordinator Costume Assistant 15 Costume Supervisor Junior Make-up & Hair Best Boy Electrician Location Assistant Best Boy Grip Rigging Gaffer 4 Data Wrangler Make Up Supervisor Video Playback Operator Scenic Artist Script Supervisor 5 Assistant Art Director Sculptor Costume Dresser Set Decorator Costume Maker Stereographer AC Nurse Post Production Co--ordinator 16 Focus Puller Sound Asst (3rd man) Production Accountant Unit Manager Stills Photographer 6 Assistant SFX technician 17 Dubbing Editor Asst. Location Manager Researcher 18 1st Assistant Director Camera Operator 7 2nd Assistant Accountant Costume Designer Clapper Loader Gaffer Draughtsperson Hair & Make Up Chief/Designer Key Grip 8 Assistant Costume Designer Production Manager Dressing Props Prosthetic Make Up Designer Graphic Artist Senior SFX Technician Sound Recordist 9 Illustrator Supervising Art Director Stand By Construction Stand By Costume 19 Individual Negotiation => Stand By Props Casting Director Storyboard Artist Director Director of Photography 10 Make Up Artist Editor Production Co-Ordinator Line Producer / UPM Production Designer 11 1st Assistant Accountant SFX Supervisor 2nd Assistant Director Senior Video Playback Operator Storeman/Asst Prop Master . -

THE CRAFTS an Introduction

THE CRAFTS An Introduction In the beginning, there was no book, no precedent, no rules set in stone. Various job jurisdictions evolved over time - not out of a sense of provincial ism, but because production crews sought out the best, most efficient delineation of responsibilities in the interest of a smooth-running production. As the film industry developed into a burgeoning new business, the flourishing studios had the resources to hire and retain the finest craftspersons in the world. Born out of this Hollywood Studio System was a tradition of unsurpassed excellence and integrity, of well-honed skills and innate talent, of veteran personnel and eager new workers - the tradition of IATSE Local 44. The varied Craft divisions within this local evolved after much thought, energy, time and debate. And the evolution continues - today the entire entertainment industry is in a state of flux due to the ever changing landscape of how the various studios are structured and do business, as well as to the extraordinary advances of technology. The present is always a product of the past, but these two eras - "then" and "now" - are quite different in a number of compelling ways. Longtime members (some of whom were present when Local 44 received its official IATSE charter in 1939) remember the early days, when working for one studio for a lifetime was the rule, not the exception. The studios kept their core ranks continually employed; if one wasn't working on a film or television project, one was working on lot improvements. IA members even played important roles in constructing studio amusement park "spinoffs," such as Disneyland and the Universal Studios Tour. -

PRESS Graphic Designer

© 2021 MARVEL CAST Natasha Romanoff /Black Widow . SCARLETT JOHANSSON Yelena Belova . .FLORENCE PUGH Melina . RACHEL WEISZ Alexei . .DAVID HARBOUR Dreykov . .RAY WINSTONE Young Natasha . .EVER ANDERSON MARVEL STUDIOS Young Yelena . .VIOLET MCGRAW presents Mason . O-T FAGBENLE Secretary Ross . .WILLIAM HURT Antonia/Taskmaster . OLGA KURYLENKO Young Antonia . RYAN KIERA ARMSTRONG Lerato . .LIANI SAMUEL Oksana . .MICHELLE LEE Scientist Morocco 1 . .LEWIS YOUNG Scientist Morocco 2 . CC SMIFF Ingrid . NANNA BLONDELL Widows . SIMONA ZIVKOVSKA ERIN JAMESON SHAINA WEST YOLANDA LYNES Directed by . .CATE SHORTLAND CLAUDIA HEINZ Screenplay by . ERIC PEARSON FATOU BAH Story by . JAC SCHAEFFER JADE MA and NED BENSON JADE XU Produced by . KEVIN FEIGE, p.g.a. LUCY JAYNE MURRAY Executive Producer . LOUIS D’ESPOSITO LUCY CORK Executive Producer . VICTORIA ALONSO ENIKO FULOP Executive Producer . BRAD WINDERBAUM LAUREN OKADIGBO Executive Producer . .NIGEL GOSTELOW AURELIA AGEL Executive Producer . SCARLETT JOHANSSON ZHANE SAMUELS Co-Producer . BRIAN CHAPEK SHAWARAH BATTLES Co-Producer . MITCH BELL TABBY BOND Based on the MADELEINE NICHOLLS MARVEL COMICS YASMIN RILEY Director of Photography . .GABRIEL BERISTAIN, ASC FIONA GRIFFITHS Production Designer . CHARLES WOOD GEORGIA CURTIS Edited by . LEIGH FOLSOM BOYD, ACE SVETLANA CONSTANTINE MATTHEW SCHMIDT IONE BUTLER Costume Designer . JANY TEMIME AUBREY CLELAND Visual Eff ects Supervisor . GEOFFREY BAUMANN Ross Lieutenant . KURT YUE Music by . LORNE BALFE Ohio Agent . DOUG ROBSON Music Supervisor . DAVE JORDAN Budapest Clerk . .ZOLTAN NAGY Casting by . SARAH HALLEY FINN, CSA Man In BMW . .MARCEL DORIAN Second Unit Director . DARRIN PRESCOTT Mechanic . .LIRAN NATHAN Unit Production Manager . SIOBHAN LYONS Mechanic’s Wife . JUDIT VARGA-SZATHMARY First Assistant Director/ Mechanic’s Child . .NOEL KRISZTIAN KOZAK Associate Producer . -

Film Crew Film Crew

FILM CREW FILM CREW The Film Crew … a typical crew engaged in a feature production. PRE-PRODUCTION During a feature production, a number of key people are brought into the project. The key roles and responsibilities include the following. The creative stage of pre-production begins with the Screenwriter. A Screenwriter creates a screenplay (a written version of a movie before it is filmed) either based on previously written material, such as a book or a play, or as an original work. A Screenwriter may write a screenplay on speculation, then try to sell it, or the Screenwriter may be hired by a Producer or studio to write a screenplay to given specifications. Screenplays are often rewritten, and it’s not uncommon for more than one Screenwriter to work on a script. A Producer is given control over the entire production of a motion picture and is ultimately held responsible for the success or failure of the motion picture project; this person is involved with the project from start to finish. The Producer's task is to organize and guide the project into a successful motion picture. The Producer would be the person who accepts the Academy Award for best picture, should the movie win one. The Producer organizes the development of the film, and is thus quite active in the pre-production phase. Once production (filming) begins, generally the role of the Producer is to supervise and give suggestions—suggestions that must be taken seriously by those creating the film. However, some Producers play a key role throughout the entire production process. -

Scott Jacobowitz 120 Concord St

Scott Jacobowitz 120 Concord St. #203 El Segundo, CA 90245 Home Phone: 310-322-9283 Cell Phone: 310-991-8078 email: [email protected] IMDB: http://www.imdb.com/name/nm2957746 Production Credits Private the Series - Webseries - Private LLC (2009) - Art Dept Coordinator, On Set Dresser, Asst Props : Producer: Mike Tarzian; Director: Dennie Gordon Father vs Son - Feature Film - Fathervsson LLC (2008) - Art Dept Coordinator/Set Dresser/Props; Producer: Paul Wolff; Director: Joe Ballarini Devolved - Feature Film - Devolved LLC (2008) - Art Dept Coordinator/Prop Master; Producer: Edrward Parks; Director: John Cregan Shipping and Receiving - Short Film - Shadow Screen Production (2008) - Production Assistant; Producer: Billy Parks; Director: O'shea Read Ballistica - Feature Film - Sofia Pictures LLC (2008) - Art Dept Assistant; Producer: Tony Kandah; Director: Gary Jones CI-X - Television Pilot - Boogie Butterfly Productions (2008) - Script Supervisor; Producer: Laurence Walsh; Director: Geoffrey McNeil Death Racers - Feature Film - The Asylum (2008) - Key Grip; Producer: David Latt; Director: Roy Sota The Kiss - Feature Film - Valley Pride Production Inc (2007) Grip/Electric; Producer: Ron Feuer; Director: Scott Madden The Other Sister - Feature Film - Touchstone Pictures (1999) Aircraft mock-up construction, Producer: David Hoberman; Director: Gary Marshall Seinfeld - The Final Episode - Castle Rock Entertainment (1998) Aircraft mock-up construction; Director: Andy Ackerman The Wedding Singer - Feature Film - New Line Cinema (1998) -

Curriculm Vitae DALTHORP

JAMES DALTHORP CREATIVE DIRECTOR, ART DIRECTOR, WRITER, PRODUCER, DIRECTOR, EDUCATOR 2215 Wroxton Road Houston, Texas 77005 310-874-4169 [email protected] EDUCATION 1975-79 UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS / AUSTIN (BFA STUDIO ART) Studied design, painting, printmaking, photography, art history, illustration, serigraphy, and completed two-year student portfolio courses from Dr. Leonard Ruben in advertising design through the Texas Art Department. Formed student run advertising agency known as “The Immaculate Conception” that included assignments from Texas Athletic Department, Britton’s, St. Edwards. Designed and produced weekly newsmagazine “Orange Power” for former 1969 National Champion James Street and Head Coach Darrell Royal. THE GLASSELL SCHOOL OF ART, THE MUSEUM OF FINE ARTS, HOUSTON 1973-1974 Studied drawing, painting, design, and sculpture TEACHING EXPERIENCE PROFESSOR, THE MIAMI AD SCHOOL / MIAMI, FLORIDA 2018-2019 “Pop Culture Engineering”- Taught graduate student course in the history of Pop Culture and its influence on marketing and communications in advertising campaigns since 1960. Reviewed the role of social media and analytics in contemporary marketing. Created strategic documents and campaign work for women’s empowerment social media initiative. Developed student campaigns for Cadillac, participated in D&AD student creative competitions. “Ideas First”- Taught students how to write and analyze a strategic brief. Reviewed case histories of successful marketing campaigns in multiple categories. Created advertising campaigns for Kate’s Real Food energy bars, JUMP cycle and scooter test market in Santa Monica, participated in the D&AD creative competitions. “The Brand You”- Worked with undergraduate MAS students as they built and perfected their individual websites. Reviewed design, functionality, layout, typography, photography, illustration, and writing loglines for their work.