Catherine Harbor Phd Dissertation Volume 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Handel's Oratorios and the Culture of Sentiment By

Virtue Rewarded: Handel’s Oratorios and the Culture of Sentiment by Jonathan Rhodes Lee A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Music in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Davitt Moroney, Chair Professor Mary Ann Smart Professor Emeritus John H. Roberts Professor George Haggerty, UC Riverside Professor Kevis Goodman Fall 2013 Virtue Rewarded: Handel’s Oratorios and the Culture of Sentiment Copyright 2013 by Jonathan Rhodes Lee ABSTRACT Virtue Rewarded: Handel’s Oratorios and the Culture of Sentiment by Jonathan Rhodes Lee Doctor of Philosophy in Music University of California, Berkeley Professor Davitt Moroney, Chair Throughout the 1740s and early 1750s, Handel produced a dozen dramatic oratorios. These works and the people involved in their creation were part of a widespread culture of sentiment. This term encompasses the philosophers who praised an innate “moral sense,” the novelists who aimed to train morality by reducing audiences to tears, and the playwrights who sought (as Colley Cibber put it) to promote “the Interest and Honour of Virtue.” The oratorio, with its English libretti, moralizing lessons, and music that exerted profound effects on the sensibility of the British public, was the ideal vehicle for writers of sentimental persuasions. My dissertation explores how the pervasive sentimentalism in England, reaching first maturity right when Handel committed himself to the oratorio, influenced his last masterpieces as much as it did other artistic products of the mid- eighteenth century. When searching for relationships between music and sentimentalism, historians have logically started with literary influences, from direct transferences, such as operatic settings of Samuel Richardson’s Pamela, to indirect ones, such as the model that the Pamela character served for the Ninas, Cecchinas, and other garden girls of late eighteenth-century opera. -

Your Tuneful Voice Iestyn Davies

VIVAT-105-Booklet.pdf 1 18/11/13 20:22 YOUR TUNEFUL VOICE Handel Oratorio Arias IESTYN DAVIES CAROLYN SAMPSON THE KING’S CONSORT ROBERT KING VIVAT-105-Booklet.pdf 2 18/11/13 20:22 YOUR TUNEFUL VOICE Handel Oratorio Arias 1 O sacred oracles of truth (from Belshazzar) [5’01] Who calls my parting soul from death (from Es ther) [3’13] with Carolyn Sampson soprano 2 Mortals think that Time is sleeping (from The Triumph of Time and Truth) [7’05] On the valleys, dark and cheerless (from The Triumph of Time and Truth) [4’00] 3 Tune your harps to cheerful strains (from Es ther) [4’45] with Rachel Chaplin oboe How can I stay when love invites (from Es ther) [3’06] 4 Mighty love now calls to arm (from Alexander Balus) [2’35] 5 Overture to Jephtha [6’47] 5 [Grave] – Allegro – [Grave] [5’09] 6 Menuet [1’38] 7 Eternal source of light divine (from Birthday Ode for Queen Anne) [3’35] with Crispian Steele-Perkins trumpet 8 Welcome as the dawn of day (from Solomon) [3’32] with Carolyn Sampson soprano 9 Your tuneful voice my tale would tell (from Semele) [5’12] with Kati Debretzeni solo violin 10 Yet can I hear that dulcet lay (from The Choice of Hercules) [3’49] 11 Up the dreadful steep ascending (from Jephtha) [3’36] 12 Overture to Samson [7’43] 12 Andante – Adagio [3’17] 13 Allegro – Adagio [1’37] 14 Menuetto [2’49] 15 Thou shalt bring them in (from Israel in Egypt) [3’15] VIVAT-105-Booklet.pdf 3 18/11/13 20:22 O sacred oracles of truth (from Belshazzar) [5’01] 16 Who calls my parting soul from death (from Es ther) [3’13] with Carolyn Sampson soprano -

5048849-8Db3fc-3760127224426 01

BUXTEHUDECANTATES POUR VOIX SEULE MANUSCRITS D’UppSAlA 1. Franz Tunder (1614-1667) Ach Herr, lass deine lieben Engelein 7‘00 (Uppsala universitetsbibliotek (S-Uu) - The Düben Collection - Vok. mus. i hs. 38:3) 2. Dietrich Buxtehude (1637-1707) Dixit Dominus - BuxWV 17 9‘29 (Uppsala universitetsbibliotek (S-Uu) - The Düben Collection - Vok. mus. i hs. 50:8) 3. Anonyme Sonata a 3 viole da gamba 8‘29 (Uppsala universitetsbibliotek (S-Uu) - The Düben Collection - Instr. mus. i hs. 11:5) 4. Johann Philipp Förtsch (1652-1732) Aus der Tiefen ruf ich Herr zu dir 8‘21 (Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin - Preußischer Kulturbesitz (D-B) - Mus.ms. 6472 (24)) 5. Dietrich Buxtehude Sonata VI d-Moll, opus 1 - BuxWV 257 9‘25 (VII. Suonate a doi, Violino & Violadagamba, con Cembalo, Opera Prima, Hamburg 1696) 6. Dietrich Buxtehude Sicut Moses - BuxWV 97 7‘39 (Uppsala universitetsbibliotek (S-Uu) - The Düben Collection - Vok. mus. i hs. 51:26) 7. Gabriel Schütz (1633-1710/11) Sonata a 2 viole da gamba 6‘23 (Durham, The Cathedral Library (GB-DRc) - MS D4 No9) 8. Christian Geist (ca.1650-1711) Resurrexi adhuc tecum sum 3‘53 (Uppsala universitetsbibliotek (S-Uu) - The Düben Collection - Vok. mus. i hs. 26:13) 9. Dietrich Buxtehude Herr, wenn ich nur dich hab - BuxWV 38 4‘42 (Uppsala universitetsbibliotek (S-Uu) - The Düben Collection - Vok. mus. i hs. 06:11) 2 TRACKS 2 PLAGES CD La Rêveuse Maïlys de Villoutreys, soprano Stéphan Dudermel, violon (2-4-5-6-8-9) Fiona-Emilie Poupard, violon (2-6-8-9) FLORENCE BOLTON & BENJAMIN PERROT Florence Bolton, dessus (1) & basse de viole (2 à 9) Andreas Linos, ténor de viole (1) La Rêveuse tient à remercier : 1. -

Violin Playing in Late Seventeenth-Century England: Baltzar, Matteis, and Purcell Mary Cyr

Performance Practice Review Volume 8 Article 5 Number 1 Spring Violin Playing in Late Seventeenth-Century England: Baltzar, Matteis, and Purcell Mary Cyr Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/ppr Part of the Music Practice Commons Cyr, Mary (1995) "Violin Playing in Late Seventeenth-Century England: Baltzar, Matteis, and Purcell," Performance Practice Review: Vol. 8: No. 1, Article 5. DOI: 10.5642/perfpr.199508.01.05 Available at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/ppr/vol8/iss1/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Claremont at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Performance Practice Review by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Baroque Violin Technique Violin Playing in Late Seventeenth-Century England: Baltzar, Matteis, and Purcell Mary Cyr Violin playing underwent distinct changes in late-17th century England. With the Restoration (and the return of Charles II from France) Lully and the French manner of playing certainly prevailed for a time. But with the ar- rival of famous violinists from abroad such as Thomas Baltzar and Nicola Matteis the English were exposed to fresh influences. The holding of the bow (the bow grip), the placement of the instrument against the body, the kinds of sonorities used on the instrument, all underwent decisive changes. These new techniques and aspects of playing undoubtedly had an effect on Purcell in his Sonnata's of III Parts for two violins and continuo (composed about 1680 and published in 1683). The "French Grip" John Playford described the bow grip commonly used in England around mid-century and thereafter: The Bow is held in the right Hand between the ends of the Thumb and three Fingers, the Thumb being stay'd upon the Hair at die Nut, and the three Fingers resting upon the Wood. -

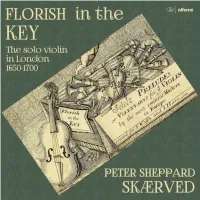

The Solo Violin in London 1650-1705

‘Florish in the Key’ – the solo violin in London 1650-1705 Played on: Anon – ‘Charles II’ Violin 1664 (tracks 1-34); Girolamo Amati – Violin 1629 (tracks 35-44) (A=416Hz) by Peter Sheppard Skærved Works from ‘Preludes or Voluntarys’ (1705) 1 Arcangelo Corelli D major Prelude 1:10 26 Marc ’Antonio Ziani F minor Prelude 2:21 2 Giuseppe Torelli E minor Prelude 2:53 27 Gottfried Finger E major Prelude 1:25 3 Nicola Cosimi A major Prelude 1:37 28 ‘Mr Hills’ A major Prelude 1:40 4 Heinrich Ignaz Franz von Biber D major Prelude 0:48 29 Johann Christoph Pepusch B flat major Prelude 1:16 5 Giovanni Bononcini D minor Prelude 1:08 30 Giuseppe Torelli C minor Prelude 1:01 6 Nicola Matteis A major Prelude 1:16 31 Nicola Francesco Haym D minor Prelude 1:14 7 Francesco Gasparini D major Prelude 1:31 32 Tomaso Giovanni Albinoni C major Prelude 1:19 8 Nicola Francesco Haym F major Prelude 0:50 33 Francesco Gasparini C major Prelude 1:33 9 Johann Gottfried Keller D major Prelude 1:44 34 Nicola Matteis C minor Prelude 2:09 10 ‘Mr Dean’ A major Prelude 2:10 11 Tomaso Giovanni Albinoni D major Prelude 1:34 Works from ‘A Set of Tunings by Mr Baltzar’) 12 William Corbett A major Prelude 1:42 35 Thomas Baltzar A major Allemande 1 1:48 13 Henry Eccles A minor Prelude 1:57 36 Thomas Baltzar A major Allemande 2 2:06 14 Arcangelo Corelli A major Prelude 1:23 37 Thomas Baltzar A major ‘Corant.’ 1:21 15 Nicola Cosimi A major Prelude 1:26 38 Thomas Baltzar A major ‘Sarabrand.’ 1:30 16 Tomaso Vitali D minor Prelude 1:31 17 John Banister B flat major Prelude 1:12 Other -

A Pilgrimage Through English History and Culture (F-L)

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Faculty Publications 2009-05-01 A Pilgrimage Through English History and Culture (F-L) Gary P. Gillum [email protected] Susan Wheelwright O'Connor Alexa Hysi Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/facpub Part of the English Language and Literature Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Gillum, Gary P.; O'Connor, Susan Wheelwright; and Hysi, Alexa, "A Pilgrimage Through English History and Culture (F-L)" (2009). Faculty Publications. 12. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/facpub/12 This Other is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. 833 FAIRFAX, JOHN, 1623-1700. Rare 922.542 St62f 1681 Presbýteros diples times axios, or, The true dignity of St. Paul's elder, exemplified in the life of that reverend, holy, zealous, and faithful servant, and minister of Jesus Christ Mr. Owne Stockton ... : with a collection of his observations, experiences and evidences recorded by his own hand : to which is added his funeral sermon / by John Fairfax. London : Printed by H.H. for Tho. Parkhurst at the Sign of the Bible and Three Crowns, at the lower end of Cheapside, 1681. Description: [12], 196, [20] p. ; 15 cm. References: Wing F 129. Subjects: Stockton, Owen, 1630-1680. Notes: Title enclosed within double line rule border. "Mors Triumphata; or The Saints Victory over Death; Opened in a Funeral Sermon ... " has special title page. 834 FAIRFAX, THOMAS FAIRFAX, Baron, 1612-1671. -

Field Dissertation 4

OUTLANDISH AUTHORS: INNOCENZO FEDE AND MUSICAL PATRONAGE AT THE STUART COURT IN LONDON AND IN EXILE by Nicholas Ezra Field A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Music: Musicology) in the University of Michigan 2013 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Stefano Mengozzi, Co-Chair Associate Professor Mark Clague, Co-Chair Professor Linda K. Gregerson Associate Professor George Hoffmann ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS In writing this dissertation I have benefited from the assistance, encouragement, and guidance of many people. I am deeply grateful to my thesis advisors and committee co-chairs, Professor Stefano Mengozzi and Professor Mark Clague for their unwavering support as this project unfolded. I would also like to extend my heartfelt gratitude to my dissertation committee members, Professor Linda Gregerson and Professor George Hoffmann—thank you both for your interest, insights, and support. Additional and special thanks are due to my family: my parents Larry and Tamara, my wife Yunju and her parents, my brother Sean, and especially my beloved children Lydian and Evan. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS................................................................................................ ii LIST OF FIGURES ............................................................................................................ v ABSTRACT....................................................................................................................... vi CHAPTER ONE: Introduction -

Handel's Last Prima Donna

SUPER AUDIO CD HANDEL’s LAST PRIMA DONNA GIULIA FRASI IN LONDON RUBY HUGHES Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment LAURENCE CUMMINGS CHANDOS early music John Christopher Smith, c.1763 Smith, Christopher John Etching, published 1799, by Edward Harding (1755 – 1840), after portrait by Johan Joseph Zoffany (1733 – 1810) © Lebrecht Music & Arts Photo Library Handel’s last prima donna: Giulia Frasi in London George Frideric Handel (1685 – 1759) 1 Susanna: Crystal streams in murmurs flowing 8:14 Air from Act II, Scene 2 of the three-act oratorio Susanna, HWV 66 (1749) Andante larghetto e mezzo piano Vincenzo Ciampi (?1719 – 1762) premiere recording 2 Emirena: O Dio! Mancar mi sento 8:35 Aria from Act III, Scene 7 of the three-act ‘dramma per musica’ Adriano in Siria (1750) Edited by David Vickers Cantabile – Allegretto premiere recording 3 Camilla: Là per l’ombrosa sponda 4:39 Aria from Act II, Scene 1 of the ‘dramma per musica’ Il trionfo di Camilla (1750) Edited by David Vickers [ ] 3 Thomas Augustine Arne (1710 – 1778) 4 Arbaces: Why is death for ever late 2:21 Air from Act III, Scene 1 of the three-act serious opera Artaxerxes (1762) Sung by Giulia Frasi in the 1769 revival Edited by David Vickers [Larghetto] John Christopher Smith (1712 – 1795) 5 Eve: Oh! do not, Adam, exercise on me thy hatred – 1:02 6 It comes! it comes! it must be death! 5:45 Accompanied recitative and song from Act III of the three-act oratorio Paradise Lost (1760) Edited by David Vickers Largo – Largo premiere recording 7 Rebecca: But see, the night with silent pace -

We Hope This Visual Guide Prepares You for Your Trip to Our Theatre. We

We hope this visual guide prepares you for your trip to our Theatre. We wish to show you what our building looks like, who you might meet and what you might experience during your visit. GETTING HERE Trafalgar Studios is a theatre in Central London. We have two performance spaces inside known as Studio 1 and Studio 2. Mostly plays are performed here and both children and adults come to watch them. The theatre is in an area of London called ‘the West End’. There are lots of theatres around here and it can be quite busy. This map shows where you can find us. There are many different ways to travel around London. You may arrive by train, taxi or bus. There are many famous London sights near Trafalgar Studios. For instance, you may see this statue on your way. It is called ‘Nelson’s Column’ and is found in Trafalgar Square. The road in the photo below is called Whitehall. This is the road that the theatre is on. The pavement in front of the entrance of the venue is raised by 2 steps. You can find a flat pavement on Spring Gardens, the street parallel to Whitehall. The closest train stations to the Trafalgar Studios are Charing Cross Station (4 min walk) and Waterloo Station (17 min walk via the Golden Jubilee Bridge). The closest tube stations are Charing Cross (1 min walk), then Leicester Square (8 min walk) and Westminster (9 min walk). There are also few underground car parks near the venue. See below: Q-Park Trafalgar, right next to Trafalgar Square (Spring Gardens, St. -

Catherine Harbor

The Birth of the Music Business: Public Commercial Concerts In London 1660–1750 Catherine Harbor Volume 2 369 Appendix A. The Register of Music in London Newspapers 1660–1750 Database A.1 Database Design and Construction Initial database design decisions were dictated by the over-riding concern that the Register of Music in London Newspapers 1660–1750 should be a source-oriented rather than a model-oriented database, with the integrity of the source being preserved as far as possible (Denley, 1994: 33-43; Harvey and Press, 1996). The aim of the project was to store a large volume of data that had no obvious structure and to provide a comprehensive index to it that would serve both as a finding aid and as a database in its own right (Hartland and Harvey, 1989: 47-50). The result was what Harvey and Press (1996: 10) term an ‘electronic edition’ of the texts in the newspapers, together with an index or coding scheme that provided an easy way of retrieving the desired information. The stored data was divided into a text base with its physical and locational descriptors, and the index database. The design and specification of the database tables was undertaken by Charles Harvey and Philip Hartland using techniques of entity-relationship modelling and relational data analysis. These techniques are discussed in numerous texts on databases and database design and have been applied to purely historical data (Hartland and Harvey, 1989; Harvey and Press, 1996: 103-130). The Oracle relational database management system was used to create the tables, enter, store and manipulate the data. -

23211Booklet.Pdf

‘Florish in the Key’ – the solo violin in London 1650-1705 Played on: Anon – ‘Charles II’ Violin 1664 (tracks 1-34) Girolamo Amati – Violin 1629 (tracks 35-44) (A=416Hz) by Peter Sheppard Skærved Works from ‘Preludes or Voluntarys’ (1705) 1 Arcangelo Corelli D major Prelude 1:10 2 Giuseppe Torelli E minor Prelude 2:53 3 Nicola Cosimi A major Prelude 1:37 4 Heinrich Ignaz Franz von Biber D major Prelude 0:48 5 Giovanni Bononcini D minor Prelude 1:08 6 Nicola Matteis A major Prelude 1:16 7 Francesco Gasparini D major Prelude 1:31 8 Nicola Francesco Haym F major Prelude 0:50 9 Johann Gottfried Keller D major Prelude 1:44 10 ‘Mr Dean’ A major Prelude 2:10 11 Tomaso Giovanni Albinoni D major Prelude 1:34 12 William Corbett A major Prelude 1:42 13 Henry Eccles A minor Prelude 1:57 14 Arcangelo Corelli A major Prelude 1:23 15 Nicola Cosimi A major Prelude 1:26 16 Tomaso Vitali D minor Prelude 1:31 17 John Banister B flat major Prelude 1:12 18 Johann Christoph Pepusch D minor Prelude 0:51 19 Ambrogio Lonati D minor Prelude 2:16 20 Henry Purcell G minor Prelude 1:06 21 ‘Mr Simons’ F minor Prelude 1:30 22 Robert King A major Prelude 1:30 23 Giovanni Battista Bassani E flat major Prelude 1:45 24 ‘Mr Smith’ E major Prelude 1:41 25 William Gorton A major Prelude 1:35 26 Marc ’Antonio Ziani F minor Prelude 2:21 27 Gottfried Finger E major Prelude 1:25 28 ‘Mr Hills’ A major Prelude 1:40 29 Johann Christoph Pepusch B flat major Prelude 1:16 30 Giuseppe Torelli C minor Prelude 1:01 31 Nicola Francesco Haym D minor Prelude 1:14 32 Tomaso Giovanni Albinoni -

Article Template

The Church of St James, Abinger, Surrey – J A Gibbs The Church of St. James Abinger, Surrey (Third Edition) Preface The Second Edition of this booklet1 issued portions of the North and South walls of the from the publishers at the very time, ironically Nave were left, and the only windows remaining enough, that our Church was destroyed on the were the three-light 15th century one and the 3rd of August, 1944,by the blast of the explosion round-headed single-light one next to it. The of a flying bomb of the enemy, which hit a roofs of all the rest of the Church and of the cypress tree just outside the West end of the Lych-gate were stripped of their external Church. This Third Edition is to be sold, as was coverings of stone Horsham slabs, tiles etc. but, the Second, for the benefit of the Rebuilding apart from the Nave, the walls of the rest of the Fund. Church remained standing. The South Aisle, consisting, of the North-east (the old) Vestry and Organ Chamber, suffered considerably and the organ was ruined, but this Aisle with its arcade that separated it from the Chancel, is to disappear when the Church is rebuilt, and a new organ will, with the choir, be situated at the West end of the Nave. The pews of the Nave were broken in pieces by the weight of the masonry that fell on them and suffered further afterwards by lying for many months deep in the rain-soddened debris. Those of the North Aisle and the Choir stalls escaped serious damage, and so did the Altar, Altar rails, Chancel screens, the two Sanctuary chairs, the Pulpit, Lectern, and Chancel carpets.