Lenses and Telescopes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Galileo and the Telescope

Galileo and the Telescope A Discussion of Galileo Galilei and the Beginning of Modern Observational Astronomy ___________________________ Billy Teets, Ph.D. Acting Director and Outreach Astronomer, Vanderbilt University Dyer Observatory Tuesday, October 20, 2020 Image Credit: Giuseppe Bertini General Outline • Telescopes/Galileo’s Telescopes • Observations of the Moon • Observations of Jupiter • Observations of Other Planets • The Milky Way • Sunspots Brief History of the Telescope – Hans Lippershey • Dutch Spectacle Maker • Invention credited to Hans Lippershey (c. 1608 - refracting telescope) • Late 1608 – Dutch gov’t: “ a device by means of which all things at a very great distance can be seen as if they were nearby” • Is said he observed two children playing with lenses • Patent not awarded Image Source: Wikipedia Galileo and the Telescope • Created his own – 3x magnification. • Similar to what was peddled in Europe. • Learned magnification depended on the ratio of lens focal lengths. • Had to learn to grind his own lenses. Image Source: Britannica.com Image Source: Wikipedia Refracting Telescopes Bend Light Refracting Telescopes Chromatic Aberration Chromatic aberration limits ability to distinguish details Dealing with Chromatic Aberration - Stop Down Aperture Galileo used cardboard rings to limit aperture – Results were dimmer views but less chromatic aberration Galileo and the Telescope • Created his own (3x, 8-9x, 20x, etc.) • Noted by many for its military advantages August 1609 Galileo and the Telescope • First observed the -

The Telescope Lenses, Which Turned the Image Upside Down but Improved the Clarity Dramatically

The image produced by the first refracting telescope was Name right side up. However, the clarity of the image was less than ideal. Johannes Kepler worked to improve the image produced by the refracting telescope. He used two convex The Telescope lenses, which turned the image upside down but improved the clarity dramatically. His design soon became popular By Phyllis Naegeli and remains in use today. Do you like to lie on your back and gaze One problem associated with the refracting telescope was at the stars? What constellations can you the rainbow halo it produced around the object in view. Sir name? Have you ever used a telescope to Isaac Newton did not care for the halo produced by the get a closer look at the universe? Do you refracting telescope. He set out to improve the design, know how a telescope works? which led him to work on the reflecting telescope. The design used a curved mirror to collect light from an object. A telescope is used to see distant objects A secondary flat mirror reflected the image to the side of up close. There are two basic types of the tube where it is viewed through an eyepiece. Newton telescopes - the refracting telescope and also used a shorter, fatter tube allowing magnification to be the reflecting telescope. Each will help increased by using larger mirrors. Newton's design you to see the planets, moon, or stars. Both eliminated the rainbow halo produced by the convex lenses use a tube and have an eyepiece to focus the image for you of the refracting telescope. -

502-13 Magnifiers and Telescopes

13-1 I and Instrumentation Design Optical OPTI-502 © Copyright 2019 John E. Greivenkamp E. John 2019 © Copyright Section 13 Magnifiers and Telescopes 13-2 I and Instrumentation Design Optical OPTI-502 Visual Magnification Greivenkamp E. John 2019 © Copyright All optical systems that are used with the eye are characterized by a visual magnification or a visual magnifying power. While the details of the definitions of this quantity differ from instrument to instrument and for different applications, the underlying principle remains the same: How much bigger does an object appear to be when viewed through the instrument? The size change is measured as the change in angular subtense of the image produced by the instrument compared to the angular subtense of the object. The angular subtense of the object is measured when the object is placed at the optimum viewing condition. 13-3 I and Instrumentation Design Optical OPTI-502 Magnifiers Greivenkamp E. John 2019 © Copyright As an object is brought closer to the eye, the size of the image on the retina increases and the object appears larger. The largest image magnification possible with the unaided eye occurs when the object is placed at the near point of the eye, by convention 250 mm or 10 in from the eye. A magnifier is a single lens that provides an enlarged erect virtual image of a nearby object for visual observation. The object must be placed inside the front focal point of the magnifier. f h uM h F z z s The magnifying power MP is defined as (stop at the eye): Angular size of the image (with lens) MP Angular size of the object at the near point uM MP d NP 250 mm uU 13-4 I and Instrumentation Design Optical OPTI-502 Magnifiers – Magnifying Power Greivenkamp E. -

Solar System Solar System

Delta Science Reader SolarSolar SystemSystem Delta Science Readers are nonfiction student books that provide science background and support the experiences of hands-on activities. Every Delta Science Reader has three main sections: Think About . , People in Science, and Did You Know? Be sure to preview the reader Overview Chart on page 4, the reader itself, and the teaching suggestions on the following pages. This information will help you determine how to plan your schedule for reader selections and activity sessions. Reading for information is a key literacy skill. Use the following ideas as appropriate for your teaching style and the needs of your students. The After Reading section includes an assessment and writing links. OVERVIEW Students will: discover facts about the Solar System In the Delta Science Reader Solar System, students take a tour of the Sun and the explore the planets and other objects in the planets. Other space objects such as dwarf Solar System planets, comets, asteroids, and meteoroids discuss the function of a table of contents, are explored. Students read about the headings, and a glossary rotation and revolution of the planets and interpret photographs and graphics to the causes of night and day, seasonal answer questions changes, and the phases of the Moon. The book describes the work of a planetary complete a KWL chart geologist. In addition, students discover organize information in a variety of ways how telescopes work. delta science modules Solar System 119 © Delta Education LLC. All rights reserved. -

Depth of Focus (DOF)

Erect Image Depth of Focus (DOF) unit: mm Also known as ‘depth of field’, this is the distance (measured in the An image in which the orientations of left, right, top, bottom and direction of the optical axis) between the two planes which define the moving directions are the same as those of a workpiece on the limits of acceptable image sharpness when the microscope is focused workstage. PG on an object. As the numerical aperture (NA) increases, the depth of 46 focus becomes shallower, as shown by the expression below: λ DOF = λ = 0.55µm is often used as the reference wavelength 2·(NA)2 Field number (FN), real field of view, and monitor display magnification unit: mm Example: For an M Plan Apo 100X lens (NA = 0.7) The depth of focus of this objective is The observation range of the sample surface is determined by the diameter of the eyepiece’s field stop. The value of this diameter in 0.55µm = 0.6µm 2 x 0.72 millimeters is called the field number (FN). In contrast, the real field of view is the range on the workpiece surface when actually magnified and observed with the objective lens. Bright-field Illumination and Dark-field Illumination The real field of view can be calculated with the following formula: In brightfield illumination a full cone of light is focused by the objective on the specimen surface. This is the normal mode of viewing with an (1) The range of the workpiece that can be observed with the optical microscope. With darkfield illumination, the inner area of the microscope (diameter) light cone is blocked so that the surface is only illuminated by light FN of eyepiece Real field of view = from an oblique angle. -

The History of Optical Astronomy, by Caroline Herschel and Lyman Spitzer

Online Modules from The University of Chicago Multiwavelength Astronomy: The History of Optical Astronomy, by Caroline Herschel and Lyman Spitzer http://ecuip.lib.uchicago.edu/multiwavelength-astronomy/optical/history/index.html Subject(s): Astronomy/Space Science Grade(s) Level: 9-12 Duration: One Class Period Objectives: As a result of reading The History of Optical Astronomy, students will be able to • Discriminate between reflecting and refracting telescope designs and describe the differences between them; • Explain how a telescope focuses light; • Articulate the limitations of ground-based telescopes and propose solutions to these limitations; • Identify important astronomical discoveries made and personages working in the optical regime; • Discuss examples of problem-solving and creativity in astronomy. Materials: Internet connection and browser for displaying the lesson. Pre-requisites: Students should be familiar with the Electromagnetic Spectrum. Before using the lesson, students should familiarize themselves with all vocabulary terms. Procedures: Students will read the lesson and answer assessment questions (listed under evaluation). Introduction: In reading this lesson, you will meet important individuals in the History of Optical Astronomy. They are: Caroline Lucretia Herschel was a German-born British astronomer and the sister of astronomer Sir William Herschel. She is the discoverer of several comets, in particular, the periodic comet 35P/Herschel-Rigollet, which bears her name. Lyman Strong Spitzer, Jr. was an American theoretical physicist, astronomer and mountaineer. He carried out research into star formation, plasma physics, and in 1946, conceived the idea of telescopes operating in outer space. Spitzer is the namesake of NASA's Spitzer Space Telescope. 1 Online Modules from The University of Chicago William Herschel was an astronomer and composer. -

The Microscope Parts And

The Microscope Parts and Use Name:_______________________ Period:______ Historians credit the invention of the compound microscope to the Dutch spectacle maker, Zacharias Janssen, around the year 1590. The compound microscope uses lenses and light to enlarge the image and is also called an optical or light microscope (vs./ an electron microscope). The simplest optical microscope is the magnifying glass and is good to about ten times (10X) magnification. The compound microscope has two systems of lenses for greater magnification, 1) the ocular, or eyepiece lens that one looks into and 2) the objective lens, or the lens closest to the object. Before purchasing or using a microscope, it is important to know the functions of each part. Eyepiece Lens: the lens at the top that you look through. They are usually 10X or 15X power. Tube: Connects the eyepiece to the objective lenses Arm: Supports the tube and connects it to the base. It is used along with the base to carry the microscope Base: The bottom of the microscope, used for support Illuminator: A steady light source (110 volts) used in place of a mirror. Stage: The flat platform where you place your slides. Stage clips hold the slides in place. Revolving Nosepiece or Turret: This is the part that holds two or more objective lenses and can be rotated to easily change power. Objective Lenses: Usually you will find 3 or 4 objective lenses on a microscope. They almost always consist of 4X, 10X, 40X and 100X powers. When coupled with a 10X (most common) eyepiece lens, we get total magnifications of 40X (4X times 10X), 100X , 400X and 1000X. -

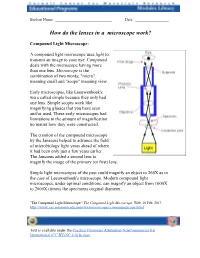

How Do the Lenses in a Microscope Work?

Student Name: _____________________________ Date: _________________ How do the lenses in a microscope work? Compound Light Microscope: A compound light microscope uses light to transmit an image to your eye. Compound deals with the microscope having more than one lens. Microscope is the combination of two words; "micro" meaning small and "scope" meaning view. Early microscopes, like Leeuwenhoek's, were called simple because they only had one lens. Simple scopes work like magnifying glasses that you have seen and/or used. These early microscopes had limitations to the amount of magnification no matter how they were constructed. The creation of the compound microscope by the Janssens helped to advance the field of microbiology light years ahead of where it had been only just a few years earlier. The Janssens added a second lens to magnify the image of the primary (or first) lens. Simple light microscopes of the past could magnify an object to 266X as in the case of Leeuwenhoek's microscope. Modern compound light microscopes, under optimal conditions, can magnify an object from 1000X to 2000X (times) the specimens original diameter. "The Compound Light Microscope." The Compound Light Microscope. Web. 16 Feb. 2017. http://www.cas.miamioh.edu/mbi-ws/microscopes/compoundscope.html Text is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International (CC BY-NC 4.0) license. - 1 – Student Name: _____________________________ Date: _________________ Now we will describe how a microscope works in somewhat more detail. The first lens of a microscope is the one closest to the object being examined and, for this reason, is called the objective. -

Binocular and Spotting Scope Basics

Binocular and Spotting Scope Basics A good pair of binoculars is a must for most for bird monitoring projects. Certainly, you can observe birds and other wildlife without the aid of binoculars, such as at a feeder, but with them you will see more detail. Binoculars don't have to cost you a lot of money, but should adequately magnify birds for identification. Many 7 x 35 or 8 x 42 power binoculars are affordable and good for bird watching. They should be easy to use and comfortable for you. You can buy binoculars through sporting goods stores, catalogs, and the Internet. How to use binoculars Binoculars are an extension of your eyes. First, use your naked eye to find the birds you are observing. Once you have detected movement and can see the wildlife, use binoculars to see details of a bird’s “field marks.” Everyone’s eyes are different, so before you raise the binoculars, you must calibrate them for your eyes. How to Calibrate Binoculars 1. Binoculars hinge at the center between the two large “barrels,” allowing the eyepieces to fit the width of your eyes (Illustration A). Pivot the hinged barrels so you see a single circle-shaped image, rather than a double-image when looking through them. If the barrels are as close together as they go and you still see two images, you may need to find another pair. The distance between the eyepieces is called the “interpupillary distance.” It is too large if you see two images. The number on the hinge post (angle) will always be the same for your eyes, no matter which binocular you use (A). -

Objective (Optics) 1 Objective (Optics)

Objective (optics) 1 Objective (optics) In an optical instrument, the objective is the optical element that gathers light from the object being observed and focuses the light rays to produce a real image. Objectives can be single lenses or mirrors, or combinations of several optical elements. They are used in microscopes, telescopes, cameras, slide projectors, CD players and many other optical instruments. Objectives are also called object lenses, object glasses, or objective glasses. Microscope objectives are typically designed to be parfocal, which means that when one changes from one lens to another on a Several objective lenses on a microscope. microscope, the sample stays in focus. Microscope objectives are characterized by two parameters, namely, magnification and numerical aperture. The former typically ranges from 5× to 100× while the latter ranges from 0.14 to 0.7, corresponding to focal lengths of about 40 to 2 mm, respectively. For high magnification applications, an oil-immersion objective or water-immersion objective has to be used. The objective is specially designed and refractive index matching oil or water must fill the air gap between the front element and the object to allow the numerical aperture to exceed 1, and hence give greater resolution at high magnification. Numerical apertures as high as 1.6 can be achieved with oil immersion.[1] To find the total magnification of a microscope, one multiplies the A photographic objective, focal length 50 mm, magnification of the objective lenses by that of the eyepiece. aperture 1:1.4 See also • List of telescope parts and construction Diastar projection objective from a 35 mm movie projector, (focal length 400 mm) References [1] Kenneth, Spring; Keller, H. -

Tools of Astronomy Notes Light Is a Form of Electromagnetic Radiation

Name_________________________________________Date____________________Period__ Tools of Astronomy Notes Light is a form of electromagnetic radiation. Scientists call the light you can see visible light. If you shine white light through a prism, the light spreads out to make a range of different colors with different wavelengths, called a spectrum. The electromagnetic spectrum includes the entire range of radio waves, microwaves infrared, visible light, ultraviolet radiation, X-rays, and gamma rays. Telescopes are instruments that collect and focus light and other forms of electromagnetic radiation. A telescope that uses lenses or mirrors to collect and focus visible light is called an optical telescope. The two major types of optical telescopes are refracting telescopes and reflecting telescopes. Telescopes used to detect radio waves from objects in space are called radio telescopes. Most radio telescopes have curved, reflecting surfaces. As with optical telescopes, the larger a radio telescope is, the more radio waves it can collect. Radio telescopes can be used day or night. They can also be used during cloudy weather because radio waves can pass through clouds. Most ultraviolet radiation, X-rays, and gamma rays are blocked by Earth’s atmosphere. To detect these wavelengths, astronomers have placed the Hubble space telescope in space. Some space telescopes also detect visible light or infrared radiation. The Earth’s atmosphere interferes with of these forms of radiation. By placing a telescope in space astronomers get a clearer picture of the universe. Spectroscopes are another useful tool for astronomers. A spectroscope breaks the light from a star into a spectrum. Each element has a unique spectrum. This allows astronomers to compare the spectrum of a star to known elements. -

6. Imaging: Lenses & Curved Mirrors

6. Imaging: Lenses & Curved Mirrors The basic laws of lenses allow considerable versatility in optical instrument design. The focal length of a lens, f, is the distance at which collimated (parallel) rays converge to a single point after passing through the lens. This is illustrated in Fig. 6.1. A collimated laser beam can thus be brought to a focus at a known position simply by selecting a lens of the desired focal length. Likewise, placing a lens at a distance f can collimate light emanating from a single spot. This simple law is widely used in experimental spectroscopy. For example, this configuration allows collection of the greatest amount of light from a spot, an important consideration in maximizing sensitivity in fluorescence or Raman measurements. The collection Figure 6.1: Parallel beams focused by a lens efficiency of a lens is the ratio Ω/4π, where Ω is the solid angle of the light collected and 4π is the solid angle over all space. The collection efficiency is related to the F-number of the lens, also abbreviated as F/# or f/n. F/# is defined as the ratio of the distance of the object from the lens to the lens diameter (or limiting aperture diameter). In Fig. 6.1 above, the f- number of lens is f/D - ! 1 = 2 . 4" $#4(F / #)&% The collection efficiency increases with decreased focal length and increased lens diameter. Collection efficiency is typically low in optical spectroscopy, such as fluorescence or Raman. On the other hand, two-dimensional imaging (as opposed to light collection) is limited when the object is at a distance of f from the lens because light from only one point in space is collected in this configuration.