Islamic and Ethnic Identities in Azerbaijan: Emerging Trends and Tensions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Volume II, Issue 2, March 2021.Pages

INTERNATIONAL COUNTER-TERRORISM REVIEW VOLUME II, ISSUE 2 February, 2021 The Revival of Islam How Do External Factors Shape the Potential Islamist Threat in Azerbaijan? FUAD SHAHBAZOV ABOUT ICTR The International Counter-Terrorism Review (ICTR) aspires to be the world’s leading student publication in Terrorism & Counter-Terrorism Studies. ICTR provides a unique opportunity for students and young professionals to publish their papers, share innovative ideas, and develop an academic career in Counter-Terrorism Studies. The publication also serves as a platform for exchanging research and policy recommendations addressing theoretical, empirical and policy dimensions of international issues pertaining to terrorism, counter-terrorism, insurgency, counter-insurgency, political violence and homeland security. ICTR is a project jointly initiated by the International Institute for Counter-Terrorism (ICT) at the Interdisciplinary Center (IDC), Herzliya, Israel and NextGen 5.0. The International Institute for Counter-Terrorism (ICT) is one of the leading academic institutes for counter-terrorism in the world. Founded in 1996, ICT has rapidly evolved into a highly esteemed global hub for counter-terrorism research, policy recommendations and education. The goal of the ICT is to advise decision makers, to initiate applied research and to provide high-level consultation, education and training in order to address terrorism and its effects. NextGen 5.0 is a pioneering non-profit, independent, and virtual think tank committed to inspiring and empowering the next generation of peace and security leaders in order to build a more secure and prosperous world. COPYRIGHT This material is offered free of charge for personal and non-commercial use, provided the source is acknowledged. -

IRN Population Movement Snapshot June 2021

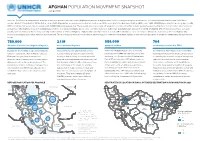

AFGHAN POPULATION MOVEMENT SNAPSHOT June 2021 Since the 1979 Soviet invasion and the subsequent waves of violence that have rocked Afghanistan, millions of Afghans have fled the country, seeking safety elsewhere. The Islamic Republic of Iran boasts 5,894 km of borders. Most of it, including the 921 km that are shared with Afghanistan, are porous and located in remote areas. While according to the Government of Iran (GIRI), some 1,400-2,500 Afghans arrive in Iran every day, recently GIRI has indicated increased daily movements with 4,000-5,000 arriving every day. These people aren’t necesserily all refugees, it is a mixed flow that includes people being pushed by the lack of economic opportunities as well as those who might be in need of international protection. The number fluctuates due to socio-economic challenges both in Iran and Afghanistan and also the COVID-19 situation. UNHCR Iran does not have access to border points and thus is unable to independently monitor arrivals or returns of Afghans. Afghans who currently reside in Iran have dierent statuses: some are refugees (Amayesh card holders), other are Afghans who posses a national passport, while other are undocumented. These populations move across borders in various ways. it is understood that many Afghans in Iran who have passports or are undocumented may have protection needs. 780,000 2.1 M 586,000 704 Amayesh Card Holders (Afghan refugees1) undocumented Afghans passport holders voluntarily repatriated in 2021 In 2001, the Government of Iran issues Amayesh Undocumented is an umbrella term used to There are 275,000 Afghans who hold family Covid-19 had a clear impact on the low VolRep cards to regularize the stay of Afghan refugees. -

Universita' Degli Studi Di Milano Bicocca

Dipartimento di Scienze Ambiente e Territorio e Scienze della Terra Università degli studi di Milano-Bicocca Dottorato di Ricerca in Scienze della Terra XXVI ciclo Earthquake-induced static stress change in promoting eruptions Tutore: Prof. Alessandro TIBALDI Co-tutore: Dott.ssa Claudia CORAZZATO Fabio Luca BONALI Matr. Nr. 040546 This work is dedicated to my uncle Eugenio Marcora who led my interest in Earth Sciences and Astronomy during my childhood Abstract The aim of this PhD work is to study how earthquakes could favour new eruptions, focusing the attention on earthquake-induced static effects in three different case sites. As a first case site, I studied how earthquake-induced crustal dilatation could trigger new eruptions at mud volcanoes in Azerbaijan. Particular attention was then devoted to contribute to the understanding of how earthquake-induced magma pathway unclamping could favour new volcanic activity along the Alaska-Aleutian and Chilean volcanic arcs, where 9 seismic events with Mw ≥ 8 occurred in the last century. Regarding mud volcanoes, I studied the effects of two earthquakes of Mw 6.18 and 6.08 occurred in the Caspian Sea on November 25, 2000 close to Baku city, Azerbaijan. A total of 33 eruptions occurred at 24 mud volcanoes within a maximum distance of 108 km from the epicentres in the five years following the earthquakes. Results show that crustal dilatation might have triggered only 7 eruptions at a maximum distance of about 60 km from the epicentres and within 3 years. Dynamic rather than static strain is thus likely to have been the dominating “promoting” factor because it affected all the studied unrested volcanoes and its magnitude was much larger. -

Nationalism, Politics, and the Practice of Archaeology in the Caucasus

-.! r. d, J,,f ssaud Artsus^rNn Mlib scoIuswVC ffiLffi pac,^^€C erplJ pue lr{o) '-I dlllqd ,iq pa11pa ,(8oyoe er4lre Jo ecr] JeJd eq] pue 'sct1t1od 'tustleuolleN 6rl Se]tlJlljd 18q1 uueul lOu soop sltll'slstSo[ocPqJJu ul?lsl?JneJ leool '{uetuJO ezrsuqdtue ol qsl'\\ c'tl'laslno aql 1V cqtJo lr?JttrrJ Suteq e:u e,\\ 3llLl,\\'ieqt 'teqlout? ,{g eldoed .uorsso.rciclns euoJo .:etqSnr:1s louJr crleuols,{s eql ul llnseJ {eru leql tsr:d snolJes uoJl uPlseJnPJ lerll JO suoluolstp :o ..sSutpucJsltu,' "(rolsrqerd '..r8u,pn"r.. roJ EtlotlJr qsllqulso ol ]duralltl 3o elqetclecctl Surqsrn8urlstp o.1". 'speecorcl ll sV 'JB ,(rnluec qlxls-pltu eql ut SutuutSeq'et3:oe9 11^ly 'porred uralse,t\ ut uotJl?ztuolol {eer{) o1 saleleJ I se '{1:clncrlled lBJlsselc uP qil'\\ Alluclrol eq] roJ eJueptlc 1r:crSoloaeqcJe uuts11311l?J Jo uollRnlele -ouoJt-loueqlpue-snseon€JuJequoueqlpuE'l?luoulJv'er8rocg'uelteq -JaZVulpJosejotrolsrqerdsqtJoSuouE}erdlelutSutreptsuoc.,{11euor8ar lsrgSurpeeco:cl'lceistqlsulleJlsnlpselduexalere^esButlele;"{qsnsecne3 reded stql cql ur .{SoloeeqJlu Jo olnlpu lecrllod eql elBltsuotuop [lt,\\ .paluroclduslp lou st euo 'scrlr1od ,(:erodueluoJ o1 polelsJUtr '1tns:nd JturcpeJe olpl ue aq or ,{Soloeuqole 3o ecrlcu'rd eq} lcedxa lou plno'{\ 'SIJIUUOC aAISOldxe ouo 3Jor{,t\ PoJe uP sl 1t 'suolllpuoJ aseql IIe UsAtD sluqle pur: ,{poolq ,{11euor1dacxo lulo^es pue salndstp lelrollrrel snor0tunu qlr,n elalder uot,3e; elllBlo^ ,(re,r. e st 1l 'uolun lel^os JeuIJoJ aql io esdelloc eqt ue,tr.3 'snsBsnBJ aql jo seldoed peu'{u oql lle ro3 ln3Sutueau 'l?Iuusllllu -

Status and Protection of Globally Threatened Species in the Caucasus

STATUS AND PROTECTION OF GLOBALLY THREATENED SPECIES IN THE CAUCASUS CEPF Biodiversity Investments in the Caucasus Hotspot 2004-2009 Edited by Nugzar Zazanashvili and David Mallon Tbilisi 2009 The contents of this book do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of CEPF, WWF, or their sponsoring organizations. Neither the CEPF, WWF nor any other entities thereof, assumes any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information, product or process disclosed in this book. Citation: Zazanashvili, N. and Mallon, D. (Editors) 2009. Status and Protection of Globally Threatened Species in the Caucasus. Tbilisi: CEPF, WWF. Contour Ltd., 232 pp. ISBN 978-9941-0-2203-6 Design and printing Contour Ltd. 8, Kargareteli st., 0164 Tbilisi, Georgia December 2009 The Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund (CEPF) is a joint initiative of l’Agence Française de Développement, Conservation International, the Global Environment Facility, the Government of Japan, the MacArthur Foundation and the World Bank. This book shows the effort of the Caucasus NGOs, experts, scientific institutions and governmental agencies for conserving globally threatened species in the Caucasus: CEPF investments in the region made it possible for the first time to carry out simultaneous assessments of species’ populations at national and regional scales, setting up strategies and developing action plans for their survival, as well as implementation of some urgent conservation measures. Contents Foreword 7 Acknowledgments 8 Introduction CEPF Investment in the Caucasus Hotspot A. W. Tordoff, N. Zazanashvili, M. Bitsadze, K. Manvelyan, E. Askerov, V. Krever, S. Kalem, B. Avcioglu, S. Galstyan and R. Mnatsekanov 9 The Caucasus Hotspot N. -

Azerbaijan Page 1 of 8

Azerbaijan Page 1 of 8 Azerbaijan BUREAU OF DEMOCRACY, HUMAN RIGHTS, AND LABOR International Religious Freedom Report 2009 October 26, 2009 The Constitution provides for freedom of religion. On March 18, 2009, however, a national referendum approved a series of amendments to the Constitution; two amendments limit the spreading of and propagandizing of religion. Additionally, on May 8, 2009, the Milli Majlis (Parliament) passed an amended Law on Freedom of Religion, signed by the President on May 29, 2009, which could result in additional restrictions to the system of registration for religious groups. In spite of these developments, the Government continued to respect the religious freedom of the majority of citizens, with some notable exceptions for members of religions considered nontraditional. There was some deterioration in the status of respect for religious freedom by the Government during the reporting period. There were changes to the Constitution that undermined religious freedom. There were mosque closures, and state- and locally sponsored raids on evangelical Protestant religious groups. There were reports of monitoring by federal and local officials as well as harassment and detention of both Islamic and nontraditional Christian groups. There were reports of discrimination against worshippers based on their religious beliefs, largely conducted by local authorities who detained and questioned worshippers without any legal basis and confiscated religious material. There were sporadic reports of societal abuses or discrimination based on religious affiliation, belief, or practice. There was some prejudice against Muslims who converted to other faiths, and there was occasional hostility toward groups that proselytized, particularly evangelical Christians, and other missionary groups. -

“SABAH Graduate” Ceremony</P>

“SABAH Graduate” ceremony was held at the Baku Convention Center on July 5. ParticipantsParticipants in the inevent the eventincluded included head headof the of Humanitarian the Humanitarian Affairs Affairs Department Department of the of Presidential the Presidential AdministrationAdministration FarahFarah Aliyeva,Aliyeva, headhead ofof thethe YouthYouth PolicyPolicy andand SportSport AffairsAffairs DepartmentDepartment ofof thethe PresidentialPresidential Administration,Administration, assistantassistant to theto the First First Vice Vice President President Yusuf Yusuf Mammadaliyev, Mammadaliyev, Minister Minister of Educationof Education Jeyhun Jeyhun Bayramov, Bayramov, members members of of parliament,parliament, heads heads of public of public and andprivate private organizations, organizations, rectors rectors of higher of higher education education institutions, institutions, media media captains, captains, education experts and students. Prior to the ceremony participants viewed “I am SABAH” exhibition in the foyer of the center. TheThe event event started started with with the the playing playing of of the the state state anthem anthem of of the the Republic Republic of of Azerbaijan, Azerbaijan, and and then then featured featured the the screening screening of a documentary on the activity of SABAH groups. HeadHead ofof thethe YouthYouth PolicyPolicy andand SportSport AffairsAffairs DepartmentDepartment ofof thethe PresidentialPresidential Administration,Administration, assistantassistant toto thethe FirstFirst ViceVice -

IAUP Baku 2018 Semi-Annual Meeting

IAUP Baku 2018 Semi-Annual Meeting “Globalization and New Dimensions in Higher Education” 18-20th April, 2018 Venue: Fairmont Baku, Flame Towers Website: https://iaupasoiu.meetinghand.com/en/#home CONFERENCE PROGRAMME WEDNESDAY 18th April 2018 Fairmont Baku, Flame Towers 18:30 Registration 1A, Mehdi Hüseyn Street Fairmont Baku, Flame Towers, 19:00-21:00 Opening Cocktail Party Uzeyir Hajibeyov Ballroom, 19:05 Welcome speech by IAUP President Mr. Kakha Shengelia 19:10 Welcome speech by Ministry of Education representative 19:30 Opening Speech by Rector of ASOIU Mustafa Babanli THURSDAY 19th April 2018 Visit to Alley of Honor, Martyrs' Lane Meeting Point: Foyer in Fairmont 09:00 - 09:45 Hotel 10:00 - 10:15 Mr. Kakha Shengelia Nizami Ganjavi A Grand Ballroom, IAUP President Fairmont Baku 10:15 - 10:30 Mr. Ceyhun Bayramov Deputy Minister of Education of the Republic of Azerbaijan 10:30-10:45 Mr. Mikheil Chkhenkeli Minister of Education and Science of Georgia 10:45 - 11:00 Prof. Mustafa Babanli Rector of Azerbaijan State Oil and Industry University 11:00 - 11:30 Coffee Break Keynote 1: Modern approach to knowledge transfer: interdisciplinary 11:30 - 12:00 studies and creative thinking Speaker: Prof. Philippe Turek University of Strasbourg 12:00 - 13:00 Panel discussion 1 13:00 - 14:00 Lunch 14:00 - 15:30 Networking meeting of rectors and presidents 14:00– 16:00 Floor Presentation of Azerbaijani Universities (parallel to the networking meeting) 18:30 - 19:00 Transfer from Farimont Hotel to Buta Palace Small Hall, Buta Palace 19:00 - 22:00 Gala -

2. JIHADI-SALAFI REBELLION and the CRISIS of AUTHORITY Haim Malka

2. JIHADI-SALAFI REBELLION AND THE CRISIS OF AUTHORITY Haim Malka ihadi-salafists are in open rebellion. The sheer audacity of the JSeptember 11, 2001 attacks, combined with Osama bin Laden’s charisma and financial resources, established al Qaeda as the leader of jihad for a decade. Yet, the Arab uprisings of 2011 and the civil war in Syria shifted the ground dramatically. More ambi- tious jihadi-salafists have challenged al Qaeda’s leadership and approach to jihad, creating deep divisions. For the foreseeable future, this crisis will intensify, and al Qaeda and its chief com- petitor, the Islamic State, will continue to jockey for position. In late 2010, the self-immolation of a despairing Tunisian street vendor inspired millions of Arabs to rise up against authoritarian governments. In a matter of weeks, seemingly impregnable Arab regimes started to shake, and a single man had sparked what decades of attacks by Islamists, including jihadi-salafi groups, had not: the overthrow of an authoritarian government. In the wake of this change, a new generation of jihadi-salafists saw unprecedented opportunities to promote their own methods, priorities, and strategy of jihad. Jihadi-salafists had very little to do with the Arab uprisings themselves, though they quickly realized the importance of capitalizing on new regional dynamics. The fall of authoritarian rulers in Tunisia, Libya, and Egypt created contested political and security environments. New governments released thou- 9 10 Jon B. Alterman sands of jailed jihadi-salafi leaders and activists. This move not only bolstered the ranks of jihadi-salafi groups, but also provided unprecedented space for them to operate locally with minimal constraints. -

Late Onset of Sufism in Azerbaijan and the Influence of Zarathustra Thoughts on Its Fundamentals

International Journal of Philosophy and Theology September 2014, Vol. 2, No. 3, pp. 93-106 ISSN: 2333-5750 (Print), 2333-5769 (Online) Copyright © The Author(s). 2014. All Rights Reserved. Published by American Research Institute for Policy Development DOI: 10.15640/ijpt.v2n3a7 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.15640/ijpt.v2n3a7 Late Onset of Sufism in Azerbaijan and the Influence of Zarathustra Thoughts on its Fundamentals Parisa Ghorbannejad1 Abstract Islamic Sufism started in Azerbaijan later than other Islamic regions for some reasons.Early Sufis in this region had been inspired by mysterious beliefs of Zarathustra which played an important role in future path of Sufism in Iran the consequences of which can be seen in illumination theory. This research deals with the reason of the delay in the advent of Sufism in Azerbaijan compared with other regions in a descriptive analytic method. Studies show that the deficiency of conqueror Arabs, loyalty of ethnic people to Iranian religion and the influence of theosophical beliefs such as heart's eye, meeting the right, relation between body and soul and cross evidences in heart had important effects on ideas and thoughts of Azerbaijan's first Sufis such as Ebn-e-Yazdanyar. Investigating Arab victories and conducting case studies on early Sufis' thoughts and ideas, the author attains considerable results via this research. Keywords: Sufism, Azerbaijan, Zarathustra, Ebn-e-Yazdanyar, Islam Introduction Azerbaijan territory2 with its unique geography and history, was the cultural center of Iran for many years in Sasanian era and was very important for Zarathustra religion and Magi class. 1 PhD, Faculty of Science, Islamic Azad University, Urmia Branch,WestAzarbayjan, Iran. -

Hong Kong's Currency Board and Changing Monetary Regimes

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES HONG KONG’S CURRENCY BOARD AND CHANGING MONETARY REGIMES Yum K. Kwan Francis T. Lui Working Paper 5723 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 August 1996 This paper was presented at NBER’s East Asian Seminar on Economics, and the NBER conference “Universities Research Conference on the Determination of Exchange Rates.” This work is part of NBER’s project on International Capital Flows which receives support from the Center for International Political Economy. We are grateful to the Center for International Political Economy for the support of this project and to Barry Eichengreen and Zhaoyong Zhang for helpful and constructive comments. Any opinions expressed are those of the authors and not those of the National Bureau of Economic Research. O 1996 by Yum K. Kwan and Francis T. Lui. All rights reserved. Short sections of text, not to exceed two paragraphs, may be quoted without explicit permission provided that full credit, including @ notice, is given to the source. NBER Working Paper 5723 August 1996 HONG KONG’S CURRENCY BOARD AND CHANGING MONETARY REGIMES ABSTRACT The paper discusses the historical background and institutional details of Hong Kong’s currency board. We argue that its experience provides a good opportunity to test the macroeconomic implications of the currency board regime. Using the method of Blanchard and Quah (1989), we show that the parameters of the structural equations and the characteristics of supply and demand shocks have significantly changed since adopting the regime. Variance decomposition and impulse response analyses indicate Hong Kong’s currency board is less susceptible to supply shocks, but demand shocks can cause greater short-term volatility under the system. -

Islamic Authority and the Articulation of Jihad: Approaching Jihadist Authority Through the Islamist Magazine Inspire

Islamic Authority and the Articulation of Jihad: Approaching Jihadist Authority through the Islamist Magazine Inspire Aleisha LaChette Thesis submitted to the faculty of the Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts In Political Science Bettina Koch, Chair Rachel Scott Luke Plotica April 29, 2015 Blacksburg, VA Keywords: jihad, Islamic authority, terrorism, Inspire magazine Copyright 2015, Aleisha LaChette Islamic Authority and the Articulation of Jihad: Approaching Jihadist Authority through the Islamist Magazine Inspire Aleisha LaChette ABSTRACT This thesis examines the impact of changing views of legitimate Islamic authority on conceptions of jihad. Spearheaded by militant Sunni movements, jihad in the modern era has taken on new purposes and practices that more closely resemble general understandings of terrorism than the regulated forms of warfare cemented during the classical period of Islam. Contrasting the historical authority of the caliph or political leader and the ‘ulama over the concept of jihad with the modern state and ‘ulama’s lack of control over the concept offers a partial explanation of the divergence of contemporary jihad from the classical or traditional views. This thesis uses the concept of individual jihad as communicated through the jihadist magazine Inspire, to counter the dismissal of radical articulations of jihad as un-Islamic and therefore illegitimate, and to demonstrate how such forms instead reflect the opportunistic replacement of traditional political and religious authority by the jihadist as the true defender of Islam and consequently the rightful interpreter of Islamic law. To Oren iii Acknowledgements This thesis would not have been possible without the guidance, encouragement and support of my committee members, Dr.