A Software for Balancing Steady-State Ecosystem Models and Calculating Network Characteristics *

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Effects of Human Disturbance on Terrestrial Apex Predators

diversity Review Effects of Human Disturbance on Terrestrial Apex Predators Andrés Ordiz 1,2,* , Malin Aronsson 1,3, Jens Persson 1 , Ole-Gunnar Støen 4, Jon E. Swenson 2 and Jonas Kindberg 4,5 1 Grimsö Wildlife Research Station, Department of Ecology, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, SE-730 91 Riddarhyttan, Sweden; [email protected] (M.A.); [email protected] (J.P.) 2 Faculty of Environmental Sciences and Natural Resource Management, Norwegian University of Life Sciences, Postbox 5003, NO-1432 Ås, Norway; [email protected] 3 Department of Zoology, Stockholm University, SE-10691 Stockholm, Sweden 4 Norwegian Institute for Nature Research, NO-7485 Trondheim, Norway; [email protected] (O.-G.S.); [email protected] (J.K.) 5 Department of Wildlife, Fish, and Environmental Studies, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, SE-901 83 Umeå, Sweden * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: The effects of human disturbance spread over virtually all ecosystems and ecological communities on Earth. In this review, we focus on the effects of human disturbance on terrestrial apex predators. We summarize their ecological role in nature and how they respond to different sources of human disturbance. Apex predators control their prey and smaller predators numerically and via behavioral changes to avoid predation risk, which in turn can affect lower trophic levels. Crucially, reducing population numbers and triggering behavioral responses are also the effects that human disturbance causes to apex predators, which may in turn influence their ecological role. Some populations continue to be at the brink of extinction, but others are partially recovering former ranges, via natural recolonization and through reintroductions. -

Provided for Non-Commercial Research and Educational Use

Provided for non-commercial research and educational use. Not for reproduction, distribution or commercial use. This article was originally published in the Encyclopedia of Ecology, Volumes 1-5 published by Elsevier, and the attached copy is provided by Elsevier for the author’s benefit and for the benefit of the author’s institution, for non-commercial research and educational use including without limitation use in instruction at your institution, sending it to specific colleagues who you know, and providing a copy to your institution’s administrator. All other uses, reproduction and distribution, including without limitation commercial reprints, selling or licensing copies or access, or posting on open internet sites, your personal or institution’s website or repository, are prohibited. For exceptions, permission may be sought for such use through Elsevier’s permissions site at: http://www.elsevier.com/locate/permissionusematerial M Scotti. Development Capacity. In Sven Erik Jørgensen and Brian D. Fath (Editor-in-Chief), Ecological Indicators. Vol. [2] of Encyclopedia of Ecology, 5 vols. pp. [911-920] Oxford: Elsevier. Author's personal copy Ecological Indicators | Development Capacity 911 animals that appear on and in dung and the processes they Cross WF, Benstead JP, Frost PC, and Thomas SA (2005) Ecological stoichiometry in freshwater benthic systems: Recent progress and initiate are highly predictable, but in detail depend on the perspectives. Freshwater Biology 50: 1895–1912. habitat and climate under investigation. Specialized copro- Findlay S and Sinsabaugh R (eds.) (2000) Dissolved Organic Matter in philous fungi, similarly, exhibit a clear sequence of Aquatic Ecosystems. San Diego: Academic Press. Flindt MR, Pardal MA, Lillebø AI, Martins I, and Marques JC (1999) utilization of their habitat, spores of early stages already Nutrient cycling and plant dynamics in estuaries: A brief review. -

Single Gene Locus Changes Perturb Complex Microbial Communities As Much As Apex Predator Loss

ARTICLE Received 5 Dec 2014 | Accepted 30 Jul 2015 | Published 10 Sep 2015 DOI: 10.1038/ncomms9235 OPEN Single gene locus changes perturb complex microbial communities as much as apex predator loss Deirdre McClean1,2, Luke McNally3,4, Letal I. Salzberg5, Kevin M. Devine5, Sam P. Brown6 & Ian Donohue1,2 Many bacterial species are highly social, adaptively shaping their local environment through the production of secreted molecules. This can, in turn, alter interaction strengths among species and modify community composition. However, the relative importance of such behaviours in determining the structure of complex communities is unknown. Here we show that single-locus changes affecting biofilm formation phenotypes in Bacillus subtilis modify community structure to the same extent as loss of an apex predator and even to a greater extent than loss of B. subtilis itself. These results, from experimentally manipulated multi- trophic microcosm assemblages, demonstrate that bacterial social traits are key modulators of the structure of their communities. Moreover, they show that intraspecific genetic varia- bility can be as important as strong trophic interactions in determining community dynamics. Microevolution may therefore be as important as species extinctions in shaping the response of microbial communities to environmental change. 1 Department of Zoology, School of Natural Sciences, Trinity College Dublin, Dublin D2, Ireland. 2 Trinity Centre for Biodiversity Research, Trinity College Dublin, Dublin D2, Ireland. 3 Centre for Immunity, Infection and Evolution, School of Biological Sciences, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh EH9 3FL, UK. 4 Institute of Evolutionary Biology, School of Biological Sciences, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh EH9 3FL, UK. 5 Smurfit Institute of Genetics, School of Genetics and Microbiology, Trinity College Dublin, Dublin D2, Ireland. -

Ascendency As Ecological Indicator for Environmental Quality Assessment at the Ecosystem Level: a Case Study

Hydrobiologia (2006) 555:19–30 Ó Springer 2006 H. Queiroga, M.R. Cunha, A. Cunha, M.H. Moreira, V. Quintino, A.M. Rodrigues, J. Seroˆ dio & R.M. Warwick (eds), Marine Biodiversity: Patterns and Processes, Assessment, Threats, Management and Conservation DOI 10.1007/s10750-005-1102-8 Ascendency as ecological indicator for environmental quality assessment at the ecosystem level: a case study J. Patrı´ cio1,*, R. Ulanowicz2, M. A. Pardal1 & J. C. Marques1 1IMAR- Institute of Marine Research, Department of Zoology, Faculty of Sciences and Technology, University of Coimbra, 3004-517, Coimbra, Portugal 2Chesapeake Biological Laboratory, Center for Environmental and Estuarine Studies, University of Maryland, Solomons, Maryland, 20688-0038, USA (*Author for correspondence: E-mail: [email protected]) Key words: network analysis, ascendency, eutrophication, estuary Abstract Previous studies have shown that when an ecosystem consists of many interacting components it becomes impossible to understand how it functions by focussing only on individual relationships. Alternatively, one can attempt to quantify system behaviour as a whole by developing ecological indicators that combine numerous environmental factors into a single value. One such holistic measure, called the system ‘ascen- dency’, arises from the analysis of networks of trophic exchanges. It deals with the joint quantification of overall system activity with the organisation of the component processes and can be used specifically to identify the occurrence of eutrophication. System ascendency analyses were applied to data over a gradient of eutrophication in a well documented small temperate intertidal estuary. Three areas were compared along the gradient, respectively, non eutrophic, intermediate eutrophic, and strongly eutrophic. Values of other measures related to the ascendency, such as the total system throughput, development capacity, and average mutual information, as well as the ascendency itself, were clearly higher in the non-eutrophic area. -

Hammill, E., & Clements, C. F. (2020

Hammill, E. , & Clements, C. F. (2020). Imperfect detection alters the outcome of management strategies for protected areas. Ecology Letters, 23(4), 682-691. https://doi.org/10.1111/ele.13475 Peer reviewed version Link to published version (if available): 10.1111/ele.13475 Link to publication record in Explore Bristol Research PDF-document This is the author accepted manuscript (AAM). The final published version (version of record) is available online via Wiley at https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/ele.13475. Please refer to any applicable terms of use of the publisher. University of Bristol - Explore Bristol Research General rights This document is made available in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite only the published version using the reference above. Full terms of use are available: http://www.bristol.ac.uk/red/research-policy/pure/user-guides/ebr-terms/ 1 Imperfect detection alters the outcome of management strategies for protected areas 2 Edd Hammill1 and Christopher F. Clements2 3 1Department of Watershed Sciences and the Ecology Center, Utah State University, 5210 Old 4 Main Hill, Logan, UT, USA 5 2School of Biological Sciences, University of Bristol, Bristol, BS8 1TQ, UK 6 Statement of Authorship. The experiment was conceived by EH following multiple 7 conversations with CFC. EH conducted the experiment and ran the analyses relating to species 8 richness, probability of predators, and number of extinctions. CFC designed and conducted all 9 analyses relating to sampling protocols. EH wrote the first draft -

Novel Trophic Cascades: Apex Predators

Opinion Novel trophic cascades: apex predators enable coexistence 1 2 3,4 Arian D. Wallach , William J. Ripple , and Scott P. Carroll 1 Charles Darwin University, School of Environment, Darwin, Northern Territory, Australia 2 Trophic Cascades Program, Department of Forest Ecosystems and Society, Oregon State University, Corvallis, OR 97331, USA 3 Institute for Contemporary Evolution, Davis, CA 95616, USA 4 Department of Entomology and Nematology, University of California, Davis, CA 95616, USA Novel assemblages of native and introduced species and that lethal means can alleviate this threat. Eradica- characterize a growing proportion of ecosystems world- tion of non-native species has been achieved mainly in wide. Some introduced species have contributed to small and strongly delimited sites, including offshore extinctions, even extinction waves, spurring widespread islands and fenced reserves [6,7]. There have also been efforts to eradicate or control them. We propose that several accounts of population increases of threatened trophic cascade theory offers insights into why intro- native species following eradication or control of non-na- duced species sometimes become harmful, but in other tive species [7–9]. These effects have prompted invasion cases stably coexist with natives and offer net benefits. biologists to advocate ongoing killing for conservation. Large predators commonly limit populations of poten- However, for several reasons these outcomes can be inad- tially irruptive prey and mesopredators, both native and equate measures of success. introduced. This top-down force influences a wide range Three overarching concerns are that most control efforts of ecosystem processes that often enhance biodiversity. do not limit non-native species or restore native communi- We argue that many species, regardless of their origin or ties [10,11], control-dependent recovery programs typically priors, are allies for the retention and restoration of require indefinite intervention [3], and many control biodiversity in top-down regulated ecosystems. -

Ecological Modelling Comparative Network Analysis Toward Characterization of Systemic Organization for Human–Environmental

Ecological Modelling 220 (2009) 3123–3132 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Ecological Modelling journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ecolmodel Comparative network analysis toward characterization of systemic organization for human–environmental sustainability Daniel A. Fiscus ∗ Biology Department, Frostburg State University, 308 Compton Science Center, Frostburg, MD 21532, USA article info abstract Article history: A preliminary study in comparative ecological network analysis was conducted to identify key assump- Available online 17 June 2009 tions and methodological challenges, test initial hypotheses and explore systemic and network structural characteristics for environmentally sustainable ecosystems. A nitrogen network for the U.S. beef supply Keywords: chain – a small sub-network of the industrial food system analyzed as a pilot study – was constructed Ecological network analysis and compared to four non-human carbon and nitrogen trophic networks for the Chesapeake Bay and the Sustainability Florida Everglades. These non-human food webs served as sustainable reference systems. Contrary to Human food web the main original hypothesis, the “window of vitality” and the number of network roles did not clearly differentiate between a human sub-network and the more complete non-human networks. The effective trophic level of humans (a partial estimate of trophic level based on the single food source of beef) was much higher (8.1) than any non-human species (maximum of 4.88). Network connectance, entropy, total dependency coefficients, -

Plant Ecology and Biostatistics

BSCBO- 203 B.Sc. II YEAR Plant Ecology and Biostatistics DEPARTMENT OF BOTANY SCHOOL OF SCIENCES UTTARAKHAND OPEN UNIVERSITY PLANT ECOLOGY AND BIOSTATISTICS BSCBO-203 BSCBO-203 PLANT ECOLOGY AND BIOSTATISTICS SCHOOL OF SCIENCES DEPARTMENT OF BOTANY UTTARAKHAND OPEN UNIVERSITY Phone No. 05946-261122, 261123 Toll free No. 18001804025 Fax No. 05946-264232, E. mail [email protected] htpp://uou.ac.in UTTARAKHAND OPEN UNIVERSITY Page 1 PLANT ECOLOGY AND BIOSTATISTICS BSCBO-203 Expert Committee Prof. J. C. Ghildiyal Prof. G.S. Rajwar Retired Principal Principal Government PG College Government PG College Karnprayag Augustmuni Prof. Lalit Tewari Dr. Hemant Kandpal Department of Botany School of Health Science DSB Campus, Uttarakhand Open University Kumaun University, Nainital Haldwani Dr. Pooja Juyal Department of Botany School of Sciences Uttarakhand Open University, Haldwani Board of Studies Late Prof. S. C. Tewari Prof. Uma Palni Department of Botany Department of Botany HNB Garhwal University, Retired, DSB Campus, Srinagar Kumoun University, Nainital Dr. R.S. Rawal Dr. H.C. Joshi Scientist, GB Pant National Institute of Department of Environmental Science Himalayan Environment & Sustainable School of Sciences Development, Almora Uttarakhand Open University, Haldwani Dr. Pooja Juyal Department of Botany School of Sciences Uttarakhand Open University, Haldwani Programme Coordinator Dr. Pooja Juyal Department of Botany School of Sciences Uttarakhand Open University, Haldwani UTTARAKHAND OPEN UNIVERSITY Page 2 PLANT ECOLOGY AND BIOSTATISTICS BSCBO-203 Unit Written By: Unit No. 1-Dr. Pooja Juyal 1, 4 & 5 Department of Botany School of Sciences Uttarakhand Open University Haldwani, Nainital 2-Dr. Harsh Bodh Paliwal 2 & 3 Asst Prof. (Senior Grade) School of Forestry & Environment SHIATS Deemed University, Naini, Allahabad 3-Dr. -

5 Reconsidering the Notion of the Organic

DK3072_book.fm Page 101 Thursday, July 27, 2006 9:43 PM Reconsidering the Notion 5 of the Organic Robert E. Ulanowicz CONTENTS 5.1 Introduction...........................................................................................................................101 5.2 Chance and Propensities ......................................................................................................103 5.3 The Origins of Organic Agency...........................................................................................105 5.4 The Integrity of Organic Systems........................................................................................107 5.5 Formalizing Organic Dynamics ...........................................................................................107 5.6 Under Occam’s Razor ..........................................................................................................110 5.7 The Organic Perspective.......................................................................................................111 Acknowledgments..........................................................................................................................112 References ......................................................................................................................................112 ABSTRACT The advent of the Enlightenment entailed a radical shift in worldviews from one wherein life dominates all events to the perspective that all phenomena ultimately are elicited by encounters between lifeless, -

Ecosystem Theory

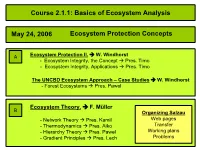

Course2.1.1: Basics of Ecosystem Analysis May 24, 2006 Ecosystem ProtectionConcepts A Ecosystem ProtectionII. à W. Windhorst -Ecosystem Integrity, theConcept à Pres. Timo -Ecosystem Integrity, Applications à Pres. Timo TheUNCBD Ecosystem Approach –CaseStudies à W. Windhorst -ForestEcosystems à Pres. Pawel Ecosystem Theory. à F. Müller B OrganizingSalzau -NetworkTheory à Pres. Kamil Web pages -Thermodynamics à Pres. Aiko Transfer -HierarchyTheory à Pres. Pawel Workingplans -Gradient Principles à Pres. Lech Problems August Macke: Felsige Landschaft, 1914, Aquarell, 24 ×20 cm, Land: Deutschland, Stil: Expressionismus. What are theories? Popper: Abstract "Theory is the fishing net description, that scientists cast explanation and to catch the world, organization to explain it of a scientific and to control it." disciplin. Theories are - sets of hypotheses empirically or deductively - non-evaluative based, aggregating and - capable of being integrating falsified representations - prognostic of the proved - applicable to knowledge of a single cases scientific disciplin. - directing the development, What orientation, and are Theories structure of the disciplin theories? Which theories are relevant for ecosystem compre- hension? Approaches: Farina: - Hierarchy Theory "Theories are interpreting - Fractal Geometry the complexity and - Chaos Theory heterogeneity of the - Catastrophe environment (landscape)" Theory - Self-Organization Naveh & Liebermann: - Information Theory "The organization of - Thermodynamics complexity in landscape - Theory of -

Reply to Roopnarine: What Is an Apex Predator?

LETTER LETTER Reply to Roopnarine: What is an apex predator? Roopnarine (1) suggests that the significance required for food (4). However, these impacts be considered apex predators as they do not of the human trophic level (HTL) (2) is re- are not a result of our being apex preda- consume the total quantity of their catch? duced because it defines the position of tors, and we feel that the fact that we are a,1 a humans in the food web by diet and is not Anne-Elise Nieblas , Sylvain Bonhommeau , not apex predators is a useful observation b c representative of our functional role in the Olivier Le Pape , Emmanuel Chassot , with consequences for our ability to reduce c c ecosystem. He is concerned that humans are Laurent Dubroca ,JulienBarde,andDavid our impacts. c compared with low trophic level omnivores To consider humans as trophic compo- M. Kaplan a and asserts that we are apex predators because nents of ecosystems was the key objective of Institut Français de Recherche pour in marine systems, our extraction of wild fish our paper. Roopnarine’s (1) point regarding l’Exploitation de la MER, Unité Mixte de is linked to high trophic level species. marine systems is indeed interesting, and we Recherche (UMR) Exploited Marine Our report demonstrates that humans are believe that the exploration of the functional Ecosystems (EME-212), 34203 Sète Cedex, low trophic level omnivores because globally role of humans in specific food webs is an France; bEcologie et santé des écosystèmes we eat more plant than meat. This fact re- exciting topic for future research. -

Behavioral Interactions Between Bacterivorous Nematodes and Predatory Bacteria in a Synthetic Community

microorganisms Article Behavioral Interactions between Bacterivorous Nematodes and Predatory Bacteria in a Synthetic Community Nicola Mayrhofer 1 , Gregory J. Velicer 1 , Kaitlin A. Schaal 1,*,† and Marie Vasse 1,2,*,† 1 Institute of Integrative Biology, ETH Zürich, Universitätstrasse 16, 8092 Zürich, Switzerland; [email protected] (N.M.); [email protected] (G.J.V.) 2 MIVEGEC (UMR 5290 CNRS, IRD, UM), CNRS, 34394 Montpellier, France * Correspondence: [email protected] (K.A.S.); [email protected] (M.V.) † Shared last authorship and these authors contributed equally to this work. Abstract: Theory and empirical studies in metazoans predict that apex predators should shape the behavior and ecology of mesopredators and prey at lower trophic levels. Despite the eco- logical importance of microbial communities, few studies of predatory microbes examine such behavioral res-ponses and the multiplicity of trophic interactions. Here, we sought to assemble a three-level microbial food chain and to test for behavioral interactions between the predatory nema- tode Caenorhabditis elegans and the predatory social bacterium Myxococcus xanthus when cultured together with two basal prey bacteria that both predators can eat—Escherichia coli and Flavobacterium johnsoniae. We found that >90% of C. elegans worms failed to interact with M. xanthus even when it was the only potential prey species available, whereas most worms were attracted to pure patches of E. coli and F. johnsoniae. In addition, M. xanthus altered nematode predatory behavior on basal prey, repelling C. elegans from two-species patches that would be attractive without M. xanthus, an effect similar to that of C.