HALL of HUMAN LIFE Summative Evaluation Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

View of the New Deal at the National Level

“THE BEST FORM OF ASSISTANCE ALWAYS IS THE KIND THAT ENABLES FOLKS TO HELP THEMSELVES”: PUBLIC REACTION TO THE NEW DEAL IN HANCOCK, SENECA, AND WOOD COUNTIES OF OHIO Anthony J. Bolton A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS May 2021 Committee: Rebecca Mancuso, Advisor Michael Brooks © 2021 Anthony J. Bolton All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Rebecca Mancuso, Advisor The Great Depression and New Deal had a profound impact on the United States. It led to the need for fundamental changes in the nation, especially regarding the federal government’s role and size. The beginning of the Great Depression marked the end of the “New Era” that the United States had experienced in the 1920s. However, one group of Americans—farmers—did not participate in this “New Era,” including those in three Northwestern Ohio counties: Hancock, Seneca, and Wood. This study analyzes through voting and media analysis how these three counties reacted to the Great Depression and the New Deal from 1929 to 1936. As the Depression continued to worsen, their suffering continued and even worsened, and with Herbert Hoover’s inability to provide relief or a path to recovery, these counties and the rest of the nation turned to Franklin Roosevelt and his promise of a “new deal” to provide that relief. Within these counties, the New Deal was initially seen as successful; however, it was soon seen as having a corrosive effect on traditional American values. Because of this, these counties rejected Roosevelt and the New Deal in 1936, while the rest of the nation overwhelmingly supported him. -

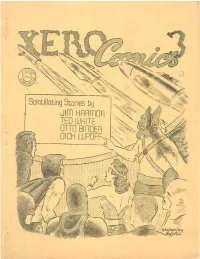

Xero Comics 3

[A/katic/Po about Wkatto L^o about ltdkomp5on,C?ou.l5on% ^okfy Madn.^5 and klollot.-........ - /dike U^eckin^z 6 ^Tion-t tke <dk<dfa............. JlaVuj M,4daVLi5 to Tke -dfec'iet o/ (2apta Ln Video ~ . U 1 _____ QilkwAMyn n 2t £L ......conducted byddit J—upo 40 Q-b iolute Keto.................. ............Vldcjdupo^ 48 Q-li: dVyL/ia Wklie.... ddkob dVtewait.... XERO continues to appall an already reeling fandom at the behest of Pat & Dick Lupoff, 21J E 7Jrd Street, New York 21, New York. Do you want to be appalled? Conies are available for contributions, trades, or letters of comment. No sales, no subs. No, Virginia, the title was not changed. mimeo by QWERTYUIOPress, as usual. A few comments about lay ^eam's article which may or lay not be helpful. I've had similar.experiences with readers joining fan clubs. Tiile at Penn State, I was president of the 3F‘Society there, founded by James F. Cooper Jr, and continued by me after he gafiated. The first meeting held each year packed them in’ the first meeting of all brought in 50 people,enough to get us our charter from the University. No subsequent meeting ever brought in more than half that, except when we held an auction. Of those people, I could count on maybe five people to show up regularly, meet ing after meeting, just to sit and talk. If we got a program together, we could double or triple that. One of the most popular was the program vzhen we invited a Naval ROTO captain to talk about atomic submarines and their place in future wars, using Frank Herbert's novel Dragon in the ~ea (or Under Pressure or 21 st Century Sub, depending upon where you read itj as a starting point. -

Thesis (4.765Mb)

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DE SAO˜ CARLOS CENTRO DE CIENCIASˆ EXATAS E DE TECNOLOGIA PROGRAMA DE POS-GRADUAC¸´ AO˜ EM CIENCIAˆ DA COMPUTAC¸ AO˜ ON THE ADVANCES IN PATTERN RECOGNITION USING OPTIMUM-PATH FOREST LUIS CLAUDIO SUGI AFONSO ORIENTADOR:PROF.DR.JOAO˜ PAULO PAPA Sao˜ Carlos – SP Setembro/2020 UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DE SAO˜ CARLOS CENTRO DE CIENCIASˆ EXATAS E DE TECNOLOGIA PROGRAMA DE POS-GRADUAC¸´ AO˜ EM CIENCIAˆ DA COMPUTAC¸ AO˜ ON THE ADVANCES IN PATTERN RECOGNITION USING OPTIMUM-PATH FOREST LUIS CLAUDIO SUGI AFONSO Tese apresentada ao Programa de Pos-Graduac¸´ ao˜ em Cienciaˆ da Computac¸ao˜ da Universidade Fed- eral de Sao˜ Carlos, como parte dos requisitos para a obtenc¸ao˜ do t´ıtulo de Doutor em Cienciaˆ da Computac¸ao,˜ area´ de concentrac¸ao:˜ Processamento de Imagens e Sinais Orientador: Prof. Dr. Joao˜ Paulo Papa Sao˜ Carlos – SP Setembro/2020 UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DE SÃO CARLOS Centro de Ciências Exatas e de Tecnologia Programa de Pós-Graduação em Ciência da Computação Folha de Aprovação Defesa de Tese de Doutorado do candidato Luis Claudio Sugi Afonso, realizada em 24/09/2020. Comissão Julgadora: Prof. Dr. João Paulo Papa (UFSCar) Prof. Dr. Alexandre Luis Magalhães Levada (UFSCar) Prof. Dr. Aparecido Nilceu Marana (UNESP) Prof. Dr. Moacir Antonelli Ponti (ICMC/USP) Prof. Dr. Anderson de Rezende Rocha (UNICAMP) O presente trabalho foi realizado com apoio da Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior - Brasil (CAPES) - Código de Financiamento 001. O Relatório de Defesa assinado pelos membros da Comissão Julgadora encontra-se arquivado junto ao Programa de Pós-Graduação em Ciência da Computação. -

Spartans Entrain for San Diego

41111111.1111111 ads fROSH EXPECT HARD CAME real IN SANTA ROSA TONIGHT lop henna to the fallow- asked Spartans Entrain It was For San Diego imittee Gridders, Band To Leave This Y ad. hat it Young Morning From Southern Pacific t , air at /as fi- Station Amid Rooters' Cheers r11F ? the im- Five Hundred' Ige to Expect .SAN JSk SIN E 857 c- I IF . is and For Nine O'clock of an. VOL. XXV Sendoff SAN JOSE, CALIFORNIA, FRIDAY, OCTOBER 23, 1936 Number 22 ads. sked to State's "determined-to-win" foot- Astrid: ball squad, led by Coach Dud De- )ids On, Groot, and assistant Bill Hubbard, nmittee will leave the Southern Pacific Varsity, ie door. Yearling Squads station this morning at 9 o'clock judge amid the cheers of approximately of the 500 students. len the Embarking on the Daylight in a special coach, the team will be II Seek tir.t Double by the band, led by Victory accompanied young Mr. Thomas Eagan and Mr. Adolph t pre. Otterstein. Sixty-seven of the band extra, Portal's members are expected to make Squad Will Meet Injuries Hurt Hopes For Its; If the long trip. nd 20 ARRIVE AT SEVEN Tough Junior College Victory In Southern Game lorun Lengthening the stop-over in I... d will Angeles, the Daylight will arriv. By WILBUR KORSMEIR By DICK EDMONDS at 7 o'clock tonight and the Santa I Not to be outdone by their older brothers, the A band of determined Spartans will leave San Fe. which will carry the Spartans Spartan Babes are to make a trip of their own and Jose this morning on a trip which may well to San Diego will not leave until decide it will leave at two o'clock this afternotm to take on the success of the 1936 grid season from a 2 o'clock tomorrow morning. -

Theatre Centre - Franco Boni

JULY 5–16, 2017 FREE PROGRAM Julianna Romanyk, Fringe Volunteer Julianna Romanyk, FRINGETORONTO.COM SHAKESPEARE IN HIGH PARK 35t H ANNIVERSARY .com king lear + twelfth night BY William Shakespeare KING LEAR DIRECTED BY Alistair Newton TWELFTH NIGHT DIRECTED BY Tanja Jacobs FEATURING Diane D’Aquila AS LEAR “A must-see summer AttrAction in toronto” - THE GLOBE AND MAIL PAY TUE - SUN @ 8PM WHAT HiGH PArK AmPHitHeAtre YOU CAN or reServe oNliNe Jun 29 – seP 3 A CANADIAN STAGE PRODUCTION IN COLLABORATION WITH THE DEPARTMENT OFTHEATRE IN THE SCHOOL OF THE ARTS, MEDIA, PERFORMANCE & DESIGN AT YORK UNIVERSITY WELCOME TO THE FRINGE! A MESSAGE FROM THE EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR Welcome to the 29th annual Toronto Fringe Festival! We are Ontario’s largest theatre festival, welcoming 160 companies and over 1,200 artists from all around the world. This year our Fringe Club migrates south on Bathurst to the Scadding Court Community Centre. Located on the south-east corner of Bathurst and Dundas, in the heart of Fringe Festival country, this outdoor urban playground features daily activities, food vendors, concerts and more. See page 11 for all the Fringe Club details. This is also the inaugural year of our Teen Fringe program with our partners at Scadding Court Community Centre and Edge of Sky Productions. Teen Fringe is a performance intensive that welcomes teens from across the GTA to train with leading professionals in acting, singing and dancing. Don’t miss the big performance when the teens take to the stage as part of the closing night show of True North Mix Tape. -

Valparaiso University Herald (March 14, 1908)

Valparaiso University ValpoScholar Old School Publications University Archives & Special Collections 3-14-1908 Valparaiso University Herald (March 14, 1908) Valparaiso University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.valpo.edu/oldschoolpubs This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the University Archives & Special Collections at ValpoScholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Old School Publications by an authorized administrator of ValpoScholar. For more information, please contact a ValpoScholar staff member at [email protected]. ~ ]t ulpurutsn llutu.rrstty f1.rrul~ Vol. II, No. 13 Saturday, March 14, 1908 Price 5 cents CALVIN S. HOD VERt who has an article in this issue of the Herald. State Sup rintendent Harmon or ivlomana made be so sluggish that the blood won't circulate a short, but excellent, address at Chapel Monday j ust log up. Then we say, 'The Lord gave and morning. He graduated here in ' 79. Mr. Harmon t1 e Lord taketh away. Blessed be the name of clos d his remarks with the following from Van t he Lord. ' Don't lay anything of that sort onto D yk the Lord.' "- President Brown. " "This is the gospel of labor, * * * Ring it y bells of t e kirk: " ay not welcome when I come, Th God of love ay not farewell when I go; Came down from above, Fo1 I come not when I come, To live with the men t hat work. And I go not when I go. For a welcom neer I'll give you, " 'This is the ros that he planted, And farew 11 will never say; H r in the thorn- ursed oil: In my heart I'm always with you, Heav n may b blest Always will be ev ry day.'' With perfect r st, -Winship. -

Wines of the Bible

can be no more conclusive evidence that we possess the spirit of Satan than the disposition to hurt and destroy those who do not appreciate our work, or who act contrary to our ideas." THE DESIRE of AGES, p. 487. Serendipity EVERAL months ago I heard the word pliments are like perfume. They are to be S serendipity and its meaning for the first smelled but not swallowed!" Such a man time. It was coined by Horace Walpole inspires confidence in God and His move after his tale of "The Three Princes of ment. Serendip." Evidently these princes had the Communion Embraces ability to accidentally make fortunate dis coveries in their travels. Thus we get the The warmth and enthusiasm of our Ital concept of having delightful experiences ian workers melt the heart. The art of and discovering blessings that come with greeting one another with a holy kiss has out looking or asking for them. not been forgotten in Italy. I wish it could This was my experience on a recent trip be restored round the world. Our meetings through the Southern European Division. in Italy climaxed with a communion serv I constantly discovered people, experiences, ice. The foot-washing experience followed and scenes that brought unsought-for bless by a holy kiss on both cheeks was a sweet ings and joy to my soul. The routine pro simple testimony of the Christian love gram of conducting workers© meetings and cradled in their hearts. I could not under fulfilling speaking engagements over a six- stand their language. I didn©t have to. -

Co: ,Staff Studentrecruitientand Retention Must'be Given First

.EI) 109. 493 95, CE 004 353 309b [Adult EdUcation Act].Replication Guide. INSTITUTION Butte Vocational-Technical Center, .tiontana. SPONS AGENCY Office of Education 4DHEW), Washington, D.C. P-UB DATE,. [ 73 ] . GRANT *.YOEG-0-7.0-51.54(324);10EG-0-71-4406(324); dEG-8-72-0072(322) NOTE .1 96p.;.For related documents, see CE 004 351-352 . ... EDRS'PRICE . _ MT-$0.16_HC-$4.43PLUS POSTAGE DESCRIPTQRS Administrator Responsibility; *Adult BaSic,Education; . *Adult Education-ProgramsAdilsory Committees; Class Organiiation; Educationally -Disadvantaged; Evaluationi, *G4idelinesCHome Instruction; /nsevide Education; Instructional Design; Instructional IN. Mat'erikrl.s; **Program Design; *Program Development; ,__ -----.Recordleeping,;-7Records;fforms)--;---Necruitment _ . IDENTIFIERS Project Homebound;%Project Pepare; The Experiment at Butte ABSth'CT The iegication guide fOr the donStrildtiOn.and- iMOlemen'tation of an -adult. basic education (ABE) prOgram is based- on three Federally funded, Butte, 0oAane demonstration projects: FrOjedt:Oomebound,:The Experitent at Butte, and Project Prepare. The 140,#Ovides specific advide and recomienilations(co: ,staff workshops, student recruitment,-class organization and jriStrUCt:i0n, inservice training, Advisory committees, 'materials, 4-- -InStrAidtiOnal design, recordkeepibg, and evaluation. .conclusions -11#4n::frcii0 the 64..moliStratin projects include: homebo,und basic intrOdtiOn is valuable for educationally disadvantaged adults unable to attend Clasives: incorporatiug teaching reflective mattriali -

Headsofsec Are Elected

Mace Elects 5 Senior Men at Convo Thurs. Else, Haumerson writer, news editor, managing e d - ............... " Marth, Peterson, iior and editor-in-chief of the VO L. 72> 21 LAWRENCE COLLEGE, APPLETON, WIS. Friday, March 20, 1951 Shields Honored Lawrentian and is a ROTC 2nd Lieutenant. The election of five senior men Shields is currently serving as to Mace, campus honorary socie president of Beta Theta Pi, after Phi Beta Kappa Elects Bunks, ty. was announced yesterday at acting as vice-president in 1952 convocation by Bruce Bigford, and assistant treasurer ln 1950. president of the group. The men He received his first football nu Spandet, Moore, Samter, Sell named were Mark Else, Robert meral as a freshman in 1949 and Haumerson, Don Marth, Robert finished his four-year career on Five Senior Women, Men Honored by Peterson and Carlton Shields. the gridiron last fall. He is a member of the L Club and the Mace is an organization, found To Show Film Classic, social committee and an ROTC , kA . # c . , Election to Wisconsin Gamma Chapter ed at Lawrence in 1911, which Captain. iVlarriaCje Ot Fl0aro I plve Lawrence college seniors honors men for outstanding He received The motion picture of Mozart’s were honored for outstanding cate a devotion "to our fellows, achievement and quality in schol scholastic hon- opera, “The Marriage of Figa-scholarahip when their election to our community, our State and our ors in the fall arship, service to the school, go", will be shown by lhe film Phi Beta Kipp. w » announced Cou„,ry> l0 encourage the low of of 1952 and du classics group at 1:30 and 3:30 before the student bodv at con- , leadership on campus, and high ring the iast W* H j next Sunday afternoon, March 22, vocation yeaterday. -

Congress Votes Everything for Big Business, Goes Home

Truman Flouts Workers of the World, Unite ! Bill of Rights T H E M f L I T A N T In Vatican Deal PUBLISHED WEEKLY IN THE INTERESTS OF THE WORKING PEOPLE By Tom Conlan The little man in the White House took another swipe Vol. X V - No. 44 NEW YORK, N. Y., MONDAY, OCTOBER 29, 1951 PRICE: FIVE CENTS at the Bill of Rights and a further step toward reaction by his latest decree ordering full diplomatic relations with the Vatican and appointing four-®--------------------------------------------- star General Mark Clark as opinion from being fully exerted Ambassador. This is a frontal on the House and Senate. As assault on the basic democratic matters stand, it will be possible principle of the separation of to bring behind-the-scenes pres church and state. sure to bear on Representatives Congress Votes Everything It comes on the heels of two and Senators to whip them in line previous usurpations of constitu by the time Congress reconvenes tional powers: Truman’s personal in January. launching of the war in Korea and Congress has obviously been his recent imposition of the news caught off guard and so have been blackout on all government de the American people. But was the partments, a body blow to the Vatican ? Or the top brass in the freedom of the press. Pentagon? You may be sure both For Big Business, Goes Home In some respects this move to were fully consulted and their embrace the Vatican is the most approval obtained in advance. So sinister to date. Consider the far as the m ilitary here are con manner in which it was done. -

Sandspur, Vol. 42 No. 05, October 28, 1936

University of Central Florida STARS The Rollins Sandspur Newspapers and Weeklies of Central Florida 10-28-1936 Sandspur, Vol. 42 No. 05, October 28, 1936 Rollins College Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/cfm-sandspur University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Newspapers and Weeklies of Central Florida at STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Rollins Sandspur by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Rollins College, "Sandspur, Vol. 42 No. 05, October 28, 1936" (1936). The Rollins Sandspur. 470. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/cfm-sandspur/470 ROLLINS CX)U.EC, „.,„.,: ^ VirslTER PARK, FtORIDA Florida's Oldest College Editorials Newspaper The SiiiiflNpur N Eollins andspur H VOLUME 42 (Weekly Student Newspaper) WINTER PARK, FLORIDA. WEDNESDAY, OCTOBER 28, 1936 (Complete Campus Coverage) NUMBER 5 LANDON DEFEATS ROOSEVELT IN STRAW VOTE DR. HOLT RELEASES WIN SANDSPUR STRAW ELECTION 347 BALLOTS CAST VIEWS GAINED ON BY ROLLINS STAFF, EXTRA - CURRICUL UM FACULTY, STUDENTS % Present Form Suggested By >* Faculty Committee Landon Receives Plurality of *» 6 Years Ago 72 Votes Over yPPER, LOWER OEAN BROWN Roosevelt ll IMPROVEMENTS SOUGHT % DIVISION HAS THOMAS POLLS 17 VOTES t Questions Members of Uni- G0E8I SPEAKER Lemke and Browder Given "l versity Club Two Votes Apiece f { llif On one of his recent trips i\ through the north. Dr. Holt, presi- AiOAL VOIG LAST SONDAY The Rollins College student \\ dent of Rollins College, publicized body, faculty and staff members views and ideas gained from the Class Officers of Both Divi voiced their protest against the [j University Club of Winter Park sions Elected His Subject Was "The Posi present Administration by giving R, on college extra-curriculums and tive Forces In Our Lives" Landon a plurality of seventy-two IJ what they should contain. -

South Sioux City Public Library

SOUTH SIOUX CITY VOLUME 4, ISSUE 10 PUBLIC LIBRARY OCTOBER 2016 South Sioux City Public Library Special Points of Interest: October at the Library Family Movies “Horror fiction Halloween Music from Freegal OCTOBER AT THE LIBRARY us as we tackle this young item will ever leave the library Tangled Yarns meets each adult title. campus. Tuesday evening at 6:30 p.m. Library Eats: Specialty Genealogy Resources Avail- The Deep End of the Breads We can’t live on bread able at the Library: The li- Ocean by Jacquelyn Mitchard alone, but good specialty brary offers two online data- the subject of the Cover to breads are a real treat. Get bases for free to library pa- Cover book discussion on some great specialty bread trons that would normally October 10, 2016 at 3:00 p.m. recipes on Thursday October cost you if you used them We will discuss part two of 13th at 6:30 p.m. personally. this novel. Gary Sides Family History Ancestory.com is available Flushed by Carl Hiaasen is Room is located in the south for library patrons to use in the title Cover to Cover will wing of the library, adjacent to the library and on the library discuss on Monday October the library meeting room. grounds. You can access An- 24th at 3:00 p.m. With their Due to limited staff, the meet- cestry from the library web- father jailed for sinking a river ing room is open by appoint- site on your computer or boat, Noah Underwood and South Sioux City ment only.