Back to the Future?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1.0 Firearms History

1.0 Firearms History 1.0.1 Introduction While a history of firearms should start with the earliest of hand cannons, progressing through the It may seem that a history of firearms is an illogical wheel lock, miquelet and so on. For this book, way to begin this book, but any competent forensic however, it will start at the flintlock, as it is unlikely firearms examiner needs to have a good working that anything earlier would be encountered in every- knowledge of this subject matter. As such, it should day case work. A much more comprehensive history form part of the court qualification process at the of firearms is offered in Appendix 4. beginning of any trial. Having said that, though, it would be unreasonable to expect a firearms examiner with many years’ experience to be able to give, for 1.0.2 The flintlock (Figure 1.0.1) example, a precise date for the introduction of the Anson and Deeley push button fore-end. Such an The flintlock ignition system really signalled the esoteric piece of firearms history may have formed advent of an easy-to-use firearm with a simple part of the examiner’s training many years ago, but mechanism for the discharge of a missile via a unless s/he had a particular interest in shotgun powdered propellant. In this type of weapon, the history it would be unlikely that s/he would remem- propellant was ignited via a spark produced by ber little other than an approximate date or period. striking a piece of flint against a steel plate. -

Intro to Reloading

Intro to Reloading This introductory manual will cover the basics of handloading ammunition. It will include information regarding necessary equipment, required materials, and the reloading process. This is not intended to be a comprehensive guide. Reloading is an in-depth, complex subject. This guide is a starting point for absolute beginners. Further information should be sought out for your specific calibers you are reloading, your specific brand and models of equipment, and your specific reloading components and materials. Follow all instructions that come with your equipment and materials. When someone who has never reloaded their own ammo looks into it, the needed equipment list is daunting and expensive. It is the intention of this guide to make reloading seem easy and accessible. Anyone, even children, can reload ammunition if shown the steps. My 8 year old is more than eager to help me de-prime, drop powder, or resize shells. Hopefully the knowledge presented here will increase your confidence when it comes to starting your reloading journey. [2] Socialistra.org Why Reload? Self Sufficiency: A decade ago, the generally accepted wisdom was “You will always be able to find .22lr. You will always be able to find .223. You will always be able to find .30-06. You will always be able to find XYZ.” After Sandy Hook in 2012, that all changed. For YEARS afterward, certain kinds of ammo were simply non-existent on store shelves. In this Time of Trump, it may not seem to make sense to spend $.10-$.25 more on each round you would make vs just buying the factory ammo. -

DCB Frequently Asked Questions

Frequently Asked Questions “The bullet with the ‘ding’ cast in!” What is the "ding" that is cast in? The „DING‰ we intend to cast into every bullet is the sound of it hitting the target you are aiming at. Because we believe our bullets will shoot consistently and more accurately we have no doubt you, and more importantly the scorers, will hear more dings after you shoot. Realistically though, since the bullets are cast from a very soft alloy (see FAQ on ÂObturationÊ) the dings you see on the bullet surface are the result of simple bumping and tapping during the casting, sorting, sizing and packaging process. These do not in any way detract from the effectiveness or accuracy of the bullet. You will notice the bullets come in a vacuum formed bag to minimize more dinging in shipping and to keep the softer lubricant in the grooves, where it belongs. And finally, the dings are very consistent with the authenticity we are trying to match in the old bullets. Have you ever seen a perfectly surfaced antique bullet? We have been experimenting with the process and handling of these softer bullets for nearly a year and have discovered that there is hardly any way to commercially cast and process them without some „dings‰. Of course we could individually hand pack them into specially designed plastic or Styrofoam cradles, then seal and box them, but the cost would be so great we couldnÊt afford to shoot them ourselves, much less find a buyer in the market. We just hope you appreciate and enjoy the accuracy, authenticity, safety and economy the bullet provides, even with the ÂsilentÊ dings. -

Driving Bands

These are the bands placed around projectiles to prevent the forward loss of gas around the projectile. They are usually made from copper, gilding metal and sometimes sintered iron. The modern day has intruded here also and they will now be encountered in plastic versions. Their use and introduction can be traced back to the time when cylindrical projectiles first appeared. The original round cannonball because of its requirement to be loaded from the muzzle had no method of sealing the bore. In fact had the ball been tight enough to seal the bore you wouldn't have been able to load the weapon at all. All this changed when the Cylindro-ogival projectile arrived on the scene along with the not-new breech loading weapons. (They had been tried many years before but failed through the inability of the gunners to adequately seal the breeches). A round cannonball needs no stabilizing. Because of its spherical shape it is inherently stable. Ask any cricketer, golfer or baseballer. On the other hand the Cylindro-ogival projectile is inherently unstable. It will not fly very well at all unless it is stabilized in some way. The two basic methods of stabilizing an elongated projectile are: • Fin stabilization and, • Spin stabilization. Both of these methods are in current use in the world today. To provide adequate stability for a projectile using fins there needs to be FIN STABILISATION. some sort of protection for the fins. The arrow of your ancient bowman would not survive in the bore of a cannon without some form of protection. -

Winchester® Components Catalog

WINCHESTER® COMPONENTS CATALOG Winchester® Powder . .02 Winchester® Primers . .03 Winchester® Wads & Shot . .04 Shotshell Reloading Data . .07 Winchester® Centerfire Rifle Data . .12 Winchester® Centerfire Handgun Data . .20 Winchester® Warnings . .25 Winchester ® Powders WST Target shotshell and standard velocity handgun propellant. Ideal for use in 45 Auto match applications. Consistent,clean, low flash and smoke are benefits to the shooter. Powder of choice for reloading AA shells. 231 As the most popular reload propellant, 231 is a pistol powder ideally suited to the 38 Special, 45 auto, and 9mm standard loads. Consistency, clean burning, low flash, and a broad range of applications make this a powder of choice on any pistol cartridge reloader’s shelf. WSF Super-Field® propellant is the propellant of choice for Winchester 20 gauge AA® Target Load and 12 gauge 3 3/4 dram equivalent Super-X® load. WSF is an ideal choice to maximize velocities in 12 gauge 1 1/8 oz. and 1 1/4 oz. loads. Super-Field also performs well in 38 Super, 9mm and 40 S&W pistol loads. Excellent propellant for fast shooting action pistol applications. 296 This propellant was developed for Winchester factory loaded ammunition for 357 magnum, 44 magnum and 410 bore. Its high loading density provides optimal velocity. 296 is also the powder type used by Winchester for factory loaded 410 bore AA loads. However, 296 is not suitable for most rifle cartridges. 748 748 is the powder of choice by Winchester and the U.S. military for 5.56mm and 223 Rem. ammunition. The low flame temperature of 748 extends barrel life versus other similar speed powders. -

Federal Ammunition for Civil War Breechloading Carbines and Rifles

Federal Ammunition for Civil War Breechloading Carbines and Rifles Dean S. Thomas According to the "Statement of ordnance and ordnance stores purchased by the Ordnance Department from January 1, 1861, to June 30, 1866," the United States Army procured more than 427,000 assorted breechloading carbines and rifles during this period.' Additional quantities were purchased from the manufacturers by various Northern states, volunteer regiments, and individual soldiers. In all, more than twenty different brands found their way onto regimental ordnance returns, and each, with rare exception, required their own peculiar form of ammunition. Captain James G. Benton of the Ordnance Department described these weapons in his book, Ordnance and Gunney: The term "breech-loading" applies to those arms in which the charge is inserted into the bore through an opening in the pered by gas leakage at the breech joint-or lack of obtura- breech; and, as far as loading is concerned, the ramrod is tion. This fault was mechanically inherent in many early dispensed with. breechloaders, but was not successfully overcome until there The interior of the barrel of a breech-loading arm is were advances in cartridge-making technology. Although the divided into two distinct parts, viz., the bore proper, or space Hall breechloading flintlock rifle was adopted by the United through which the projectile moves under the influence of the States in 1819 (and a carbine in the 1830s), they did not have powder; and the chamber in which the charge is deposited. the merits of later weapons with metallic cartridge cases. The diameter of the chamber is usually made a little larger, and Most of the early advances in breechloading ammuni- that of the bore a little smaller, than that of the projectile; this tion were made in France. -

Winchester Reloading Manuals

15th Edition Reloader’s Manual What’s it take to manufacture the world’s finest ammunition? The world’s finest components. Winchester understands the demands of shooters and hunters want- ing to develop the “perfect load.” You can rest assured that every Winchester ammu- nition component is made to meet and exceed the most demanding requirements and performance standards in the world– yours. Winchester is the only manufacturer which backs up its data with over 125 years of experience in manufacturing rifle, handgun and shotshell ammunition.The data in this booklet are the culmination of very extensive testing which insures the reloader the best possible results. This 15th edition contains more than 150 new recipes, including AA Plus® Ball Powder® propellant, WAA12L wad, 9x23 Winchester and 454 Casull. This information is presented to furnish the reloader with current data for reloading shotshell and centerfire rifle and handgun ammunition. It is not a textbook on how to reload, but rather a useful reference list of recommended loads using Winchester® components. TABLE OF CONTENTS Warnings Read Before using Data. 2 Components Section. 6 Shotshell Reloading. 12 Shotshell Data. 17 Powder Bushing Information. 25 Metallic Cartridge Reloading. 33 Rifle Data. 35 Handgun Data. 42 Ballistic Terms and Definitions. 51 TRADEMARK NOTICE AA Plus, AA, Action Pistol, Fail Safe, Lubalox, Lubaloy, Silvertip, Super-Field, Super-Lite, Super-Match, Super-Target, Super-X, Xpert and Winchester are registered trademarks of Olin Corporation. Magnum Rifle, and Upland, are trademarks of Olin Corporation. Ball Powder is a registered trademark of Primex Technologies, Inc. © 1997 Winchester Group, Olin Corporation, East Alton, IL 62024 1 WARNINGS Read before using data The shotshell and metallic cartridge data in this booklet supersede all previous data published for Ball Powder® smokeless propellants. -

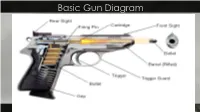

Basic Gun Diagram Types of Firearms O Shotgun: Smoothbore Gun Designed Mostly to Shoot Lead Pellets of Varying Sizes

Basic Gun Diagram Types of Firearms o Shotgun: Smoothbore gun designed mostly to shoot lead pellets of varying sizes o Rifle: A firearm having rifling in the bore and designed to be fired from the shoulder Types of Firearms (cont…) o Handguns: o Revolver: A firearm, usually a handgun, with a cylinder having several chambers so arranged as to rotate around an axis and be discharged successively by the same firing mechanism. o Semi-automatic Pistol: A repeating firearm requiring a separate pull of the trigger for each shot fired, and which uses the energy of discharge to perform a portion of the operating or firing cycle Ammunition Ammunition consists of four components: o Propellant o Projectile o Cartridge case o Primer o Self-contained ammunition, in which the propellant, projectile, and primer are held together by a cartridge case, is called fixed ammunition Ammunition bsapp.com bsapp.com bsapp.com bsapp.com Caliber of the Cartridge Caliber is a measure the diameter of the cartridge in hundredths of an inch. Common calibers include .22, .25, .357, .38, .44, and .45. Why should the caliber of ammunition match the firearm that shoots it? If they do not match, what could go wrong? Forensic Science: Fundamentals & 10 Investigations, Chapter 17 The Width of a Bullet determines Its Caliber Cartridge Cases The modern cartridge case serves several important functions: Contains the other components (projectile, primer, propellant) in a single unit for convenience of handling and loading Resists the firing-pin blow during ignition Forms a gas seal (obturation) Cartridge Case Identification Like bullets, cartridge cases can be identified as having been fired by a specific firearm. -

Deadlands Armory’S “Breech-Loading Rifles” Page for a History of Westley Richards.)

Handguns Part II. Breech-Loading Single-Shot Pistols Breech-Loading The mid-nineteenth century was a time of great innovation in the field of firearms. People began the century dueling with the same flintlock pistols as their fathers and grandfathers, and ended with a plethora of options including caplocks, single-shot breech-loaders, pepperbox pistols, revolvers, and the first magazine-fed semi-automatics. By the time breech-loading rifles began to supplant muzzle-loaders in the early 1860s, most handguns were already using some form of revolving cylinder. Still, a few breech-loading pistols made their way to the market, particular those designed by Frank Wesson, Joshua Stevens, and Remington. Like their larger cousins, such pistols require some form of mechanical action to open the breech, chamber the round, and reseal the breech. Because handguns do not require the same range and accuracy as rifles, creating an effective system of “obturation”—sealing the breech during discharge to prevent the escape of hot gas—is not as important to pistols as it is to rifles and carbines. Frank Wesson’s “tip-up” loading Rollin White Pistol “swivel down” loading COPYRIGHT 2018 BY A. BUELL RUCH. PAGE 1 OF 23 Cartridges Another important mid-century innovation was the metal cartridge, in which the bullet, propellant, and primer are encased within the same unit. The round is discharged when the firing pin strikes the base of the cartridge, setting off the primer. Because metal expands when heating, the hot casing forms a gas seal, directing the explosive energy forward. Such cartridges, usually made from brass (and before the mid-1870s, copper) are designated as “rimfire” or “centerfire” depending on where the firing pin strikes the case. -

And Lastly, by a Taper-Reamer for the Gas-Che

CONSTRUCTION OF NAVAL GUNS roughing slope bit; fourth, by a finish packed bit; fifth, by a finish slope bit; and lastly, by a taper-reamer for the gas-che<;k slope. The finishing bits are long, of the exact diameter of the chamber (that is, ground so as to bore to the exact diameter) . For guns having the enlarged chamber, as the 6-inch, Mark VI, and 12- inch, Mark III, a different method is pursued. The chamber is nrst roughed out with a hog bit, .then two packed bits are used and two slope bits. The powder chamber being larger than the mouth (or entrance) must be bored with a special boring bar and tool. This bar is hollowed, and is provided with a cutter that can be set out any desired amount by means of internal gearing worked from the outside clear of the breech. Finally the gas-check slope is finished with a taper-reamer. The chambers for R. F. guns are tapered to receive fixed ammu nition. Usually they are roughed out to desired taper, using a boring bar carrying a cutter fed in by hand, the rear end of bar being thrown out of line with gun's axis. Chambers having a straight part, and the compression slope, are roughed out with a packed bit. The finishing cut is now taken with a long packe;:l bit, or reamer, ground so as to bore the chamber to exact dimen sions. This bit mllst be very accurately made and carefully in spected by the officer supervising the work. -

Firearm Identification in the Forensic Science Laboratory

FIREARM IDENTIFICATION By Robert M. Thompson Christopher Chiles President Scott Burns Executive Director John Wilkinson Program Manager, Gun Violence Prosecution Program 2010 by the National District Attorneys Association This project was supported by the Bureau of Justice Assistance under grant number 2008-MU-MU-K004 awarded to the National District Attorneys Association. The Bureau of Justice Assistance is a component of the U.S. Department of Justice’s Office of Jus- tice Programs, which also includes the Bureau of Justice Statistics, the National Insti- tute of Justice, the office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, and the Office for Victims of Crime. Points of view or opinions in this document do not necessarily rep- resent the official positions or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice of the National District Attorneys Association. GUN VIOLENCE PROSECUTION PROGRAM A program of the National District Attorneys Association 44 Canal Center Plaza, Suite 110 Alexandria, VA 22314 www.ndaa.org FIREARM IDENTIFICATION IN THE FORENSIC SCIENCE LABORATORY By Robert M. Thompson Program Manager for Forensic Data Systems Office of Law Enforcement Standards National Institute of Standards and Technology CONTENTS 7 Introduction 9 The Science of Firearm Identification 12 The Production of Firearm Toolmarks on the Fired Cartridge 26 The Examination Process and Trial Preparation 31 Appendix and Glossary INTRODUCTION F OR A P RO S E C U TO R to be successful, he following: the interior of the barrel, the cham- or she must be cognizant of the expectations of ber, parts of the action, and ammunition mag- today’s jury. Thanks to the modern electronic azine components. -

Deadlands Armory

Rifles Part II. Breech-Loading and Metal Cartridges Breechloaders Since the dawn of black powder, gunmakers have explored ways of loading firearms from the opposite—and significantly closer!—end of the barrel. Hinged breeches, loading gates, and detachable chambers date back to the matchlock period, and even Henry VIII owned a few guns loaded in a manner not unlike a “Trapdoor” Springfield. However, such experimental firearms were prohibitively expensive, and never achieved anything more than novelty status among the wealthy. It was not until the nineteenth century that improvements in engineering techniques and ammunition types made breech-loading firearms a viable alternative to muzzle-loaders. A New Age In the early1860s, breech-loading firearms finally began to supplant muzzle-loaders. While the difference may appear minor—the rifle is loaded from the rear of the barrel, rather than the muzzle—the implications are enormous. Faster to reload, requiring less auxiliary equipment, and easier to clean, breech-loading rifles could achieve significantly higher rates of fire—up to ten rounds a minute in the hands of an experience shooter! They can also be reloaded from a prone or sitting position. The trade-off comes with an increase in complexity, as breech-loaders require some form of mechanical “action” to open the breech, expose the chamber, and reseal the breech. Most breech-loaders are classified by the system used to accomplish this process, which usually involves the movements of the “breechblock,” the metal component which physically seals the breech-end of the barrel and permits the rifle to be fired safely. Merrill Carbine with the breechblock opened, 1858–1861 COPYRIGHT 2018 BY A.