Does Linking Ethical Investment with Fairtrade Certification Enhance Credit Outcomes for Small

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fair Trade As an Example

Draft for Journal of Social Enterprise (In press) What Does it Mean To Do Fair Trade? Ontology, praxis, and the ‘Fair for Life’ certification system _____________________________________________________________________ Abstract The article discusses dynamics of interpretation concerned with what it means to do fair trade. Moving beyond the tendency to see heterogeneous practices as parallel interpretations of a separate concept – usually defined with reference to the statement by F.I.N.E – the paper seeks to provide an ontological account of the subject by drawing on theories of language, and John Searle’s notion of “institutional facts”. In seeking to establish the value of interpreting discourse and practice as mutually constitutive of the fair trade concept itself, the paper applies this alternative theoretical framework to both an historical account of fair trade movement and critical analysis of a new alternative certification programme: Fair for Life. Overall, analysis compliments political economy explanations for alternative fair trade approaches with a deeper theorisation of how such competition plays out in linguistic constructions and the wider understanding of the fair trade concept itself: a dynamic that, it is argued, will play a significant role in dictating the nature and therefore impact of fair trade governance, both now and in the future. 1 Draft for Journal of Social Enterprise (In press) Introduction One of the most prominent themes within the academic analysis of fair trade is the heterogeneous nature of practices associated with the term. This issue has been explored from the historical perspective (Gendron et al. 2009; Low and Davenport 2006) and much work addresses how the fair trade movement has been impacted by the development of third-party certification (Edward and Tallontire 2009; Renard 2005). -

Fairtrade Certification, Labor Standards, and Labor Rights Comparative Innovations and Persistent Challenges

LAURA T. RAYNOLDS Professor, Department of Sociology, Director, Center for Fair & Alternative Trade, Colorado State University Email: [email protected] Fairtrade Certification, Labor Standards, and Labor Rights Comparative Innovations and Persistent Challenges ABSTRACT Fairtrade International certification is the primary social certification in the agro-food sector in- tended to promote the well-being and empowerment of farmers and workers in the Global South. Although Fairtrade’s farmer program is well studied, far less is known about its labor certification. Helping fill this gap, this article provides a systematic account of Fairtrade’s labor certification system and standards and com- pares it to four other voluntary programs addressing labor conditions in global agro-export sectors. The study explains how Fairtrade International institutionalizes its equity and empowerment goals in its labor certifica- tion system and its recently revised labor standards. Drawing on critiques of compliance-based labor stand- ards programs and proposals regarding the central features of a ‘beyond compliance’ approach, the inquiry focuses on Fairtrade’s efforts to promote inclusive governance, participatory oversight, and enabling rights. I argue that Fairtrade is making important, but incomplete, advances in each domain, pursuing a ‘worker- enabling compliance’ model based on new audit report sharing, living wage, and unionization requirements and its established Premium Program. While Fairtrade pursues more robust ‘beyond compliance’ advances than competing programs, the study finds that, like other voluntary initiatives, Fairtrade faces critical challenges in implementing its standards and realizing its empowerment goals. KEYWORDS fair trade, Fairtrade International, multi-stakeholder initiatives, certification, voluntary standards, labor rights INTRODUCTION Voluntary certification systems seeking to improve social and environmental conditions in global production have recently proliferated. -

Participatory Analysis of the Use and Impact of the Fairtrade Premium The

Participatory analysis of the use and impact of the fairtrade premium Response from the commissioning agencies, Fairtrade Germany and Fairtrade International, to an independent mixed-methods study of use and impact of Fairtrade Premium conducted by Laboratoire Interdisciplinaire Sciences Innovations Sociétés (LISIS). The study at a Glance Introduction Researchers from the Laboratoire Interdisciplinaire Sciences Innovations Sociétés (LISIS) conducted a mixed-methods based study with the aim of analysing how the Fairtrade Premium has been used by Fairtrade organizations and how it generates benefits for Fairtrade farmers, workers and their communities. Five cases were explored: a coffee/cocoa small-scale producer organization (SPO) in Peru, a cocoa SPO in Côte d’Ivoire, a banana SPO in Ecuador, a banana SPO in Peru, and flower plantation in Kenya. Fairtrade Premium is one of the key interventions in the Fairtrade approach, as distinct from the Fairtrade Minimum Price. The Fairtrade Premium is an extra sum of money, paid on top of the selling price, that farmers or workers invest in projects of their choice. Over time, rules governing the use of Fairtrade Premium evolved to allow producer organizations to have greater autonomy over how Premium could be used. While Fairtrade case studies and examples of Fairtrade Premium projects exist, this study is the first to explore the pathways to impact that the Fairtrade Premium creates for Fairtrade producer organizations and their members. Approach The researchers followed Fairtrade’s Theory of Change in reviewing existing findings from other published studies, which suggested that the Fairtrade Premium is used to invest in farmers and workers, their organizations and communities (direct outputs of the Premium intervention). -

The International Fair Trade Charter

The International Fair Trade Charter How the Global Fair Trade Movement works to transform trade in order to achieve justice, equity and sustainability for people and planet. Launched on 25 September 2018 Copyright TransFair e.V. CONTENTS OVERVIEW CHAPTER THREE 03 OVERVIEW 17 FAIR TRADE’S UNIQUE APPROACH 04 ABOUT THE INTERNATIONAL FAIR 18 CREATING THE CONDITIONS TRADE CHARTER FOR FAIR TRADE 06 THERE IS ANOTHER WAY 19 ACHIEVING INCLUSIVE ECONOMIC GROWTH 07 IMPORTANT NOTICE ON USE OF THIS CHARTER 19 PROVIDING DECENT WORK AND HELPING TO IMPROVE WAGES AND INCOMES 20 EMPOWERING WOMEN CHAPTER ONE 20 PROTECTING THE RIGHTS OF CHILDREN AND INVESTING IN THE NEXT GENERATION 09 INTRODUCTION 21 NURTURING BIODIVERSITY AND THE ENVIRONMENT 10 BACKGROUND TO THE CHARTER 23 INFLUENCING PUBLIC POLICIES 10 OBJECTIVES OF THE CHARTER 23 INVOLVING CITIZENS IN BUILDING 11 FAIR TRADE’S VISION A FAIR WORLD 11 DEFINITION OF FAIR TRADE CHAPTER FOUR CHAPTER TWO 25 FAIR TRADE’S IMPACT AND ACHIEVEMENTS 13 THE NEED FOR FAIR TRADE 28 APPENDIX 29 NOTES Pebble Hathay Bunano AN OVERVIEW AN OVERVIEW AN OVERVIEW OF THE INTERNATIONAL FAIR TRADE CHARTER There is another way 02 03 AN OVERVIEW AN OVERVIEW “Fair Trade is based on modes of production THE RICHEST 1% NOW OWN AS MUCH WEALTH AS THE REST and trading that put people and planet before OF THE WORLD financial profit.” ABOUT THE INTERNATIONAL FAIR TRADE CHARTER All over the world and for many cen- Trade actors explain how their work con- turies, people have developed econom- nects with the shared values and generic ic and commercial relations based on approach, and to help others who work mutual benefit and solidarity. -

Fair Trade 1 Fair Trade

Fair trade 1 Fair trade For other uses, see Fair trade (disambiguation). Part of the Politics series on Progressivism Ideas • Idea of Progress • Scientific progress • Social progress • Economic development • Technological change • Linear history History • Enlightenment • Industrial revolution • Modernity • Politics portal • v • t [1] • e Fair trade is an organized social movement that aims to help producers in developing countries to make better trading conditions and promote sustainability. It advocates the payment of a higher price to exporters as well as higher social and environmental standards. It focuses in particular on exports from developing countries to developed countries, most notably handicrafts, coffee, cocoa, sugar, tea, bananas, honey, cotton, wine,[2] fresh fruit, chocolate, flowers, and gold.[3] Fair Trade is a trading partnership, based on dialogue, transparency and respect that seek greater equity in international trade. It contributes to sustainable development by offering better trading conditions to, and securing the rights of, marginalized producers and workers – especially in the South. Fair Trade Organizations, backed by consumers, are engaged actively in supporting producers, awareness raising and in campaigning for changes in the rules and practice of conventional international trade.[4] There are several recognized Fairtrade certifiers, including Fairtrade International (formerly called FLO/Fairtrade Labelling Organizations International), IMO and Eco-Social. Additionally, Fair Trade USA, formerly a licensing -

Towards a Global Programme on Market Access: Opportunities and Options

Towards a Global Programme on Market Access: Opportunities and Options Report prepared for IFAD1 Sheila Page April 2003 ODI 111, Westminster Bridge Road London SE1 7JD Tel: +44 20 7922 0300 Fax: +44 20 7922 0399 Email: [email protected] Contents Summary 1 Market access as an instrument of development 3 What do we mean by market access? 5 Poverty and markets 7 The stages of ‘market access’ 7 Awareness of possibility of exporting 8 Familiarity with buyers 8 Familiarity with standards, including health and safety 9 Access to equipment and other inputs 10 Access to investment capital 10 Access to working capital 10 Access to appropriate labour 10 Technology 11 Organisation and orientation of firm 11 Legal regimes 11 Transport and communications, local 11 Transport and communications, international 12 Tariffs and non-tariff barriers 12 Other trading conditions 13 Which problems matter, for how long? 13 Different ways of providing market access: advantages and disadvantages 14 Direct foreign investment and ownership 14 Large direct private buyers 15 Initiatives by developing country producers 16 Alternative trading companies 17 Export promotion agencies (and other local government policy) 21 Import promotion agencies 22 Aid programmes 23 Targeted technical research 24 Agencies promoting small production 25 Complementarities and differences among market structures 26 Possible initiatives by IFAD 30 2 Table 1 How different initiatives affect the necessary conditions for market access 33 Table 2 Direct and Indirect Effects on Poverty 35 Table -

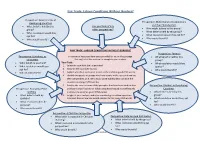

Fair Trade: Labour Conditions Without Borders?

Fair Trade: Labour Conditions Without Borders? Perspective: Governments of Perspective: Multi-National Corporations Developing Countries and their Shareholders • What belief is held by this Can you think of any • Who might belong to this group? group? other perspectives? • What belief is held by this group? • What resolution would they opt for? • What resolution would they opt for? • Who would benefit? • Who would benefit? FAIR TRADE: LABOUR CONDITIONS WITHOUT BORDERS? Perspective: Farmers Perspective: Ourselves, as A number of resources have been provided for you in this package. • What belief is held by this consumers Use any/ all of the material to complete your analysis. group? Your Task: • What belief do you hold? • What resolution would they 1. Select an issue from the list provided. • What resolution would you opt for? 2. Describe the issue (150 words) opt for? • Who would benefit? 3. Explain why this is an issue of justice or the common good (150 words). • Who would benefit? 4. Identify the people or groups who have a stake in the issue and analyse their perspectives on it. Why would some stakeholders not want the situation to change? (750 words) 5. Analyse the issue in terms of the principles that have been studied that Perspective: Workers in Developing Perspective: Economist Peter promote human flourishing. Which perspective would most effectively Countries Griffiths promote the common good? (750 words) • What belief is held by this • What belief is held by 6. In light of your analysis, and after considering the ethical questions group? Griffiths? provided, discuss how you would respond to this issue. -

Faq I Fair Trade Winnipeg

__ I FAQ I FAIR TRADE WINNIPEG FAIR TRADE WINNIPEG WHO IS FAIR TRADE WINNIPEG? COMMITTEE FairTrade Winnipeg is a collaborative, community-based working group that includes fair MEMBERS trade advocates from government, the private sector and civil society. The Fair Trade Winnipeg steering committee was formed in 2014 to achieve the common Donna Dagg goal of making Winnipeg a Fair Trade Town. In 2017, Fair Trade Winnipeg accomplished that Manitoba Liquor goal and the City of Winnipeg was officially designated as Canada’s 25th Fair Trade Town. In & Lotteries order to maintain this designation for years to come, the committee will continue to advance fair trade in partnership with the City of Winnipeg; building support through community Zack Gross awareness, involvement, and product availability. Fair Trade Manitoba Naomi Johnson WHAT IS A FAIR TRADE TOWN? Canadian A Fair Trade Town is a community where people and organizations use their everyday choices Foodgrains Bank and buying power to increase sales of Fairtrade Certified products and bring about positive Larissa Kanhai change for farmers and workers in developing countries. The Fair Trade Town program in University of Canada is part of a global movement that recognizes more than 1,850 communities in 32 Manitoba countries, that have taken steps to advance fair trade. There are 24 other Fair Trade Towns in Canada, including major cities like Vancouver, Edmonton and Toronto; and in Manitoba, Gimli, Lindsay Mierau Brandon and Selkirk. Winnipeg is now Canada’s 25th Fair Trade Town and Manitoba’s 4th. City of Winnipeg Program qualifications are managed by the Canadian FairTrade Network (www.cftn.ca) and Kyra Moshtaghi Nia Fairtrade Canada (www.fairtrade.ca) Canadian Fair Trade Network WHAT DOES IT MEAN TO BE A FAIR TRADE TOWN? Megan Redmond In order to be officially designated as a Fair Trade Town, a city must: Manitoba Council for International 1. -

Timeline of Sustainable Development (Emergence of Anthropocene)

Timeline of Sustainable Development (Emergence of Anthropocene) ~200000 years ago: appearance of modern Homo sapiens. 50000 to 10000 BCE: Quaternary (Pleistocene to Holocene) megafauna extinctions (more than half of all species >40kg, especially Australia and Americas – human predation a significant contributor). ~11700 years ago, last Ice Age ends giving rise to modern climate era and flourishing of humanity. Rock pigeons believed to be first domesticated animals about 10000 years ago. 7000 BC: Jericho (pop 2000) thought to be longest continuously inhabited city. 4000 BC: Feng Shui philosophy of harmony between environment and physical landscape. 3000 BC: Knossos, Crete believed to establish first landfill (miden). 500 BC: Athens introduces law requiring waste be dumped at least 1 mile from city; Sun Tzu’s The Art of War and strategy of resource use and planning. 202 BC: travel begins on the silk road. 376: influx of Goths into Roman Empire – thought to be pivotal point in decline of the Empire. c. 825: first appearance in print of numerical analysis by mathematicians al-Khwarizmi and al- Kindi (introduction of algebra, trigonometry – imported to Italy by Fibonacci 300 years later) 859: Fatima al-Firhi founds first degree-granting university in Fez, Morocco. 960-1279: Song dynasty flourishes in China, thought to be first to use of paper currency, earliest use of inoculations against smallpox, spreads to Ottoman Empire (becomes widespread post-1721 when Mary Wortley Montagu – wife of British Ambassador to Turkey – inoculates her own children). 1215: Magna Carta establishes English constitutional tradition. 1347: Stora Kopparberg, Sweden, oldest commercial corporation, receives Royal Charter. c. -

Activist Social Entrepreneurship: a Case Study of the Green Campus Co-Operative

Activist Social Entrepreneurship: A Case Study of the Green Campus Co-operative By: Madison Hopper Supervised By: Rod MacRae A Major Paper submitted to the Faculty of Environmental Studies In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master in Environmental Studies York University, Toronto, Ontario, Canada 31 July 2018 1 Table of Contents ABSTRACT .......................................................................................................................................................... 3 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS .................................................................................................................................. 4 FOREWORD........................................................................................................................................................ 7 INTRODUCTION: WHO’S TO BLAME?.......................................................................................................... 9 CHAPTER 1: LITERATURE REVIEW ........................................................................................................... 12 SOCIAL ENTERPRISES ............................................................................................................................................... 12 Hybrid Business Models ..................................................................................................................................... 13 Mission Quality - TOMS shoes .......................................................................................................................... -

Fairtrade, Certification, and Labor: Global and Local Tensions in Improving Conditions for Agricultural Workers

Fairtrade, certification, and labor: global and local tensions in improving conditions for agricultural workers Laura T. Raynolds Agriculture and Human Values Journal of the Agriculture, Food, and Human Values Society ISSN 0889-048X Volume 31 Number 3 Agric Hum Values (2014) 31:499-511 DOI 10.1007/s10460-014-9506-6 1 23 Your article is protected by copyright and all rights are held exclusively by Springer Science +Business Media Dordrecht. This e-offprint is for personal use only and shall not be self- archived in electronic repositories. If you wish to self-archive your article, please use the accepted manuscript version for posting on your own website. You may further deposit the accepted manuscript version in any repository, provided it is only made publicly available 12 months after official publication or later and provided acknowledgement is given to the original source of publication and a link is inserted to the published article on Springer's website. The link must be accompanied by the following text: "The final publication is available at link.springer.com”. 1 23 Author's personal copy Agric Hum Values (2014) 31:499–511 DOI 10.1007/s10460-014-9506-6 Fairtrade, certification, and labor: global and local tensions in improving conditions for agricultural workers Laura T. Raynolds Accepted: 21 April 2014 / Published online: 30 April 2014 Ó Springer Science+Business Media Dordrecht 2014 Abstract A growing number of multi-stakeholder initia- Introduction tives seek to improve labor and environmental standards through third-party certification. Fairtrade, one of the most Fair trade has emerged over recent years as a popular ini- popular third-party certifications in the agro-food sector, is tiative to socially regulate global markets, particularly in currently expanding its operations from its traditional base the agro-food sector. -

The Marketing of Fair Trade Coffee and Its Implications for Sustainable Development

Mainstreaming the Alternative? The marketing of fair trade coffee and its implications for Sustainable Development Vhairi Tollan, 4th Year, Sustainable Development __________________________________________________________________________ Coffee is the most widely traded agricultural product, with consumption doubling in the last forty years as the drink has come to form part of a modern affluent lifestyle in the Global North (Tucker, 2011). While much of the literature on sustainable food production focuses on the ability of local, place-based networks to increase the resilience of their communities, coffee production brings the questions of sustainable agriculture to a global scale. Whilst it is important that communities increase their self-sufficiency by investing in local agricultural practices, the reality of today’s globalised world means that a sustainable paradigm shift is also necessary for international agricultural trade in products such as coffee. The fair trade movement has emerged to respond to the inequalities in the current system and advocate for an alternative trade model, working to pay farmers an equitable price for their products as well as re-invest money in long-term development initiatives (Raynold, 2009). As CaféDirect’s Medium Roast coffee is the only independent fair trade coffee to be sold in St Andrews’ Tesco branch, as of October 2012, this product shall be used to explore the process through which coffee is produced and traded on the international market, and explore how the product’s social justice commitments are communicated to consumers. This essay shall begin by discussing the significance of coffee and how it came to be an important cultural product, describing the commodity chain that links producers to consumers.