Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Population and Housing Census 2014

MALDIVES POPULATION AND HOUSING CENSUS 2014 National Bureau of Statistics Ministry of Finance and Treasury Male’, Maldives 4 Population & Households: CENSUS 2014 © National Bureau of Statistics, 2015 Maldives - Population and Housing Census 2014 All rights of this work are reserved. No part may be printed or published without prior written permission from the publisher. Short excerpts from the publication may be reproduced for the purpose of research or review provided due acknowledgment is made. Published by: National Bureau of Statistics Ministry of Finance and Treasury Male’ 20379 Republic of Maldives Tel: 334 9 200 / 33 9 473 / 334 9 474 Fax: 332 7 351 e-mail: [email protected] www.statisticsmaldives.gov.mv Cover and Layout design by: Aminath Mushfiqa Ibrahim Cover Photo Credits: UNFPA MALDIVES Printed by: National Bureau of Statistics Male’, Republic of Maldives National Bureau of Statistics 5 FOREWORD The Population and Housing Census of Maldives is the largest national statistical exercise and provide the most comprehensive source of information on population and households. Maldives has been conducting censuses since 1911 with the first modern census conducted in 1977. Censuses were conducted every five years since between 1985 and 2000. The 2005 census was delayed to 2006 due to tsunami of 2004, leaving a gap of 8 years between the last two censuses. The 2014 marks the 29th census conducted in the Maldives. Census provides a benchmark data for all demographic, economic and social statistics in the country to the smallest geographic level. Such information is vital for planning and evidence based decision-making. Census also provides a rich source of data for monitoring national and international development goals and initiatives. -

Updated Environment and Social Management Plan

UPDATED ENVIRONMENT January 2020 AND SOCIAL MANAGEMENT PLAN FOR ESTABLISHMENT OF ISLAND WASTE RESOURCE MANAGEMENT CENTRE (IWRMC) IN TH. KIBIDHOO PROPOSED BY: MINISTRY OF ENVIRONMENT PREPARED BY: HAMDHOON MOHAMED (EIA P03/2017) Table of Contents List of Figures ................................................................................................................................................ 6 List of Tables ................................................................................................................................................. 7 Consultants Declaration ................................................................................................................................ 9 Executive Summary ..................................................................................................................................... 10 ާާސާލުޙާާާދާސ .................................................................................................................................................... 12 CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................................... 14 1.1 Aims and Objectives of the project ............................................................................................. 14 1.2 Current situation in solid waste management and project rationale ......................................... 14 1.3 Project Proponent ...................................................................................................................... -

Regional Waste Management Facility at Thilafushi – Greater Male Waste to Energy Project

Greater Male Waste to Energy Project (RRP MLD 51077-003) Land Acquisition and Resettlement Due Diligence Report ____________________________________________________________________________ Document Stage: Draft Project Number: P51077-003 February 2020 MLD: Regional Waste Management Facility at Thilafushi – Greater Male Waste to Energy Project Prepared by the Ministry of Environment (MOE), Government of Maldives for the Asian Development Bank. This Due Diligence Report is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. Greater Male Waste to Energy Project (RRP MLD 51077-003) CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (as of 4 February 2020) Currency unit – Rufiyaa (Rf) Rf1.00 = $0.06 $1.00 = Rf15.46 ABBREVIATIONS ADB Asian Development Bank DDR Due Diligence report DBO Design Based Operation RWMF Regional Waste Management Facility SPS Safeguard Policy Statement SWM Solid Waste Management tpd Tonnes per Day WTE Waste To Energy NOTE In this report, "$" refers to United States dollars CONTENTS PAGE I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................ 1 A. Project Background 1 B. Project Description 1 C. Scope of this Report 2 II. SUB-PROJECT DESCRIPTION ..................................................................................... 3 III. FIELD WORK AND PUBLIC CONSULTATION .............................................................. 8 A. Outline of field work 8 B. Public Consultation 8 IV. LAND AVAILABILITY AND RESETTLEMENT IMPACTS ............................................... 8 V. -

Nassimo Thila and Banana Reef, North Male' Atoll, Maldives

Socioeconomic Monitoring for Coastal Managers of South Asia: Field Trials and Baseline Surveys Nassimo Thila and Banana Reef, North Male’ Atoll, Maldives Project completion Report: NA10NOS4630055 Prepared By Marie Saleem March 2012 This volume contains the results of the Socioeconomic Assessment and monitoring project supported by IUCN/ NOAA Prepared by: 1. Seamarc Pvt. Ltd, M. Honey Dew, Izzudheen Magu, Male’, Maldives 2. Divers Association of Maldives, M. Anthias, Male’, Maldives Citation: Saleem, M. (2012). Socioeconomic Monitoring and Assessment for Coral Reef Management at Nassimo Thila and Banana Reef, Kaafu Atoll, Maldives Acknowledgements: We would like to extend our sincere thanks to the following individuals and organisations for their ongoing support and inputs: 1. Ms. Christy Loper, Scott Frew and Eileen Alicea, NOAA, USA 2. Mary Beth West and Ang Sherpa, IUCN, USA 3. Maeve Nightingale, IUCN, Asia 4. Dr. Mohamed Shiham Adam, MRC, Maldives 5. Huraa Island Council 6. Himmafushi Island Council 7. Vineeta Hoon, CARESS, India We would also like to express our heartfelt thanks to the dynamic Socmon Maldives Team and all those who participated in the surveys. Cover illustration: Kamille Le Berre 2 Table of Contents Introduction ........................................................................................5 Aims and Objectives ...........................................................................9 Study Area ........................................................................................10 Methodology .....................................................................................12 -

Common Plants of the Maldives Common Plants Common Plants of the Maldives Is a Starting Point for People Interested in Learning About Trees and Shrubs of the Maldives

series 1 series 1 Common plants of the Maldives Common plants Common Plants of the Maldives is a starting point for people interested in learning about trees and shrubs of the Maldives. It contains of the Maldives descriptions and photographs to help identify local plants as well as information on traditional uses in the Maldives and throughout the world. Whether you’re relaxing in your deck-chair or exploring the island vegetation, you will come to learn that all plants, within every ecosystem are not only beautiful but important for our survival as they provide food, medicine, soil stability, fresh air and water. books in this series are: Common Plants of the Maldives, Common Birds of the Maldives and Life on the Beach, Maldives. series 1 series 1 series 1 Common plants Common birds life on the beach of the Maldives of the Maldives Maldives LIVE&LEARN Environmental Education www.livelearn.org Common plants of the Maldives LIVE&LEARN Environmental Education Haa Alifu Atoll Haa Dhaalu INDIAN OCEAN The Maldives Atoll m There are Shaviyani Atoll approximately 1190 islands in the Maldives with some Noonu Atoll form of vegetation on Raa Atoll them. Lhaviyani Atoll m Approximately 200 are inhabited Baa Atoll islands and 990 are uninhabited. m There are 26 distinct Kaafu Atoll (Malé Atoll) geographical atolls. Alifu Alifu Atoll These are divided MALÉ into 20 administrative regions, with the Alifu Dhaalu Atoll capital Male’ making up a separate Vaavu Atoll administrative unit. Faafu Atoll m The Maldives is 860km long and Meemu Atoll 130km wide. Dhaalu Atoll m More than 99% of the country is water (115,000km2) with Thaa Atoll less than 0.3% land (300km2). -

37327 Public Disclosure Authorized

37327 Public Disclosure Authorized REPUBLIC OF THE MALDIVES Public Disclosure Authorized TSUNAMI IMPACT AND RECOVERY Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized JOINT NEEDS ASSESSMENT WORLD BANK - ASIAN DEVELOPMENT BANK - UN SYSTEM ki QU0 --- i 1 I I i i i i I I I I I i Maldives Tsunami: Impact and Recovery. Joint Needs Assessment by World Bank-ADB-UN System Page 2 ABBREVIATIONS ADB Asian Development Bank DRMS Disaster Risk Management Strategy GDP Gross Domestic Product GoM The Government of Maldives IDP Internally displaced people IFC The International Finance Corporation IFRC International Federation of Red Cross IMF The International Monetary Fund JBIC Japan Bank for International Cooperation MEC Ministry of Environment and Construction MFAMR Ministry of Fisheries, Agriculture, and Marine Resources MOH Ministry of Health NDMC National Disaster Management Center NGO Non-Governmental Organization PCB Polychlorinated biphenyls Rf. Maldivian Rufiyaa SME Small and Medium Enterprises STELCO State Electricity Company Limited TRRF Tsunami Relief and Reconstruction Fund UN United Nations UNFPA The United Nations Population Fund UNICEF The United Nations Children's Fund WFP World Food Program ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This report was prepared by a Joint Assessment Team from the Asian Development Bank (ADB), the United Nations, and the World Bank. The report would not have been possible without the extensive contributions made by the Government and people of the Maldives. Many of the Government counterparts have been working round the clock since the tsunami struck and yet they were able and willing to provide their time to the Assessment team while also carrying out their regular work. It is difficult to name each and every person who contributed. -

Itinerary 10 Days / 9 Nights Ari (Alif) Atoll and Felidhe (Vaavu) Atoll

Itinerary 10 days / 9 nights Ari (Alif) Atoll and Felidhe (Vaavu) Atoll Day 1: Hulhumale Lagoon – Banana Reef – Kohdhipparu – 3h30 (14.2NM) Embarkation in the lagoon of Hulhumale' at 2pm, after a 20 min transfer by boat from the international airport of Male'. After 30 min. sailing, arrival at Banana Reef (North Male' Atoll) a superb snorkeling site where you will certainly see manta rays. Set sail towards the Ari Atoll and anchorage in the lagoon named Kohdhipparu (3 hours) where you will spend the night. Day 2: Rasdhoo – 4h00 (21.3NM) After 4hours of sailing you will arrive at Rasdhoo a local island where you can enjoy the local life style while having tea, coffee or cold drinks at the local coffee shops located in front of the port. After snorkeling in the lagoon and exploring the area you will spend the night in the lagoon of Rasdhoo. Day 3: Genburugau – Dhigga – Fesdhoo – 5h00 (21NM) Sail for 2h30mins and arrive to a beautiful snorkeling site named Genburugau. After 1h45mins sailing lunch at Dhigga, a reef with an abundance of marine life and corals. Sail for 45mins and the night will be spend in the Lagoon of Fesdhoo. Day 4: Moofushi – Enboodhoo – Rahddhiggaa – 3h30 (16.5NM) Sail for 2 hours to arrive at the lagoon of Moofushi. After 45mins sailing arrive at the uninhabited island Enboodhoo where you can explore the island’s natural beauty by taking a tour around the island, snorkel or relax on the beach. Sail for 45mins to the picnic island Rahddhiggaa where you can enjoy the beach or snorkel with colourful fishes and abundance of marine life in the surrounding lagoon. -

Vaguthee Inthikhab Committee

RASHU STEERING COMMITTEE 2020 Vaguthee Inthikhaabee Committee Haa Alif Atoll Island # Name Mobile No 1 Abdulla Rauf * 7781947 Vashafaru 2 Mahasin Mohamed 9642399 3 Moosa Haleem 7215549 1 Nazima Naeem 9736544 Hoarafushi 2 Moosa Mahir * 7845416 3 Hudha Abdhul Ganee 9949410 1 Aishath Suha * 7373916 Kela 2 Aishath Naziya 7568186 3 Aminath Thahuzeema 9136555 1 Fathimath Rahsha * 9942305 Utheemu 2 Fathimath Nuzuha 7688598 3 Aishath Ahmeema 7757203 1 Moosa Latheef * 7752000 Dhihdhoo 2 Aminath Rasheedha 7426560 3 Mariyam Saeedha 9762768 1 Moosa Naaf Ahmed 9567267 Filladhoo 2 Adam Nazeel * 9768148 3 Ahmed Faiz 9668070 1 Ahmed Athif * 9880528 Muraidhoo 2 Yoosuf Saeed 7869044 3 Aminath Baduriyya 9136005 1 Ali Shameem * 9999590 Baarah 2 Abdulla Afeef Ali 9502500 3 Aminath Nazma 7644034 1 Moosa Abdul Hafeez * 7980013 Ihavandhoo 2 Mohamed Shujau 7907031 3 Ahmed Shathir 7793159 1 Asma Ahmed * 7666651 Thuraakunu 2 Fariyaal Ibrahim 7626268 3 Ameena Abdul Rahmaan 7558293 1 Ahmed Arif * 7745638 Thakandhoo 2 Aimath Zeena 7875291 3 Rasheedha Mohamed 7903071 1 Aminath Nasira * 9142255 Maarandhoo 2 Fathimath Shiuna 9676760 3 Lamaah Hamid 9682363 1 Ibrahim Abul Rasheed * 7329399 Molhadhoo 2 Fathimath Azlifa 7818774 3 Ahmed Shiyam 7660669 * Committee Chair RASHU STEERING COMMITTEE 2020 Vaguthee Inthikhaabee Committee Noonu Atoll 1 Asma Abubakur 7887568 Magoodhoo 2 Majidha Hassan * 7892711 3 Agila Hussain 7941173 1 Shaheema Moosa 7586159 Fohdhoo 2 Ahmed Amjad * 7857473 3 Rasheedha Yoosuf 7896905 1 Nuzuhath Thahkhaan * 7535717 Henbadhoo 2 Mariyam Nahula 9572936 -

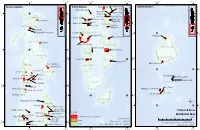

Protected Areas Distribution

73°0'0"E 74°0'0"E 73°0'0"E 74°0'0"E 73°0'0"E 74°0'0"E Northern Maldives Central Maldives Rasfari beyru Huraa Mangrove Area Southern Maldives Laamu Atoll Rasdhoo Madivaru Girifushi Thila Banana Reef Nassimo Thila 7°0'0"N 7°0'0"N Kuda Haa Lions Head Hans Hass Place; HP Reef Haa Alifu Atoll Mayaa Thila &% Kari beyru Thila Baarah Kulhi Emboodhoo Alifu Alifu Atoll Kanduolhi Orimas Thila 4°0'0"N Kaafu Atoll 4°0'0"N Haa Dhaalu Atoll Fish Head Guraidhoo &% Kanduolhi &% Keylakunu Neykurendhoo Mangrove Hurasdhoo Alifu Dhaalu Atoll 1°0'0"N 1°0'0"N Kudarah Thila Hithaadhoo Rangali Kandu Dhevana Kandu Shaviyani Atoll &% Farukolhu South Ari Atoll MPA Vaavu Atoll Filitheyo Kandu Gaafu Alifu Atoll Vattaru Kandu 6°0'0"N 6°0'0"N Faafu Atoll Noonu Atoll Gaafu Dhaalu Atoll Fushee Kandu Meemu Atoll 3°0'0"N Hakuraa Thila 3°0'0"N Kuredu Express Dhigulaabadhoo Raa Atoll &% Dhaalu Atoll &% Fushivaru Thila 0°0'0" 0°0'0" &% Bathala Region Anemone City &% Lhaviyani Atoll Mendhoo Region Angafaru Thoondi Area Dhandimagu Kilhi &% Maahuruvalhi &% &% &% &% Hanifaru Bandaara Kilhi Thaa Atoll Gnaviyani Atoll Baa Atoll Dhigali Haa &% 5°0'0"N Olhugiri 5°0'0"N Kan'di hera The Wreck of Corbin&% &% Hithadhoo Protected Area Goidhoo Koaru &% Seenu Atoll Mathifaru Huraa British Loyalty 2°0'0"N 2°0'0"N Laamu Atoll Makunudhoo channel &% Kaafu Atoll ¶ Rasfari beyru&% Huraa Mangrove Area 1°0'0"S 1°0'0"S &% Rasdhoo Madivaru &% Girifushi Thila &% Protected Areas &% Nassimo Thila &% Legend Kuda Haa &%Male' CityBanana Reef Kari beyru Thila &% &% Distribution Map Mayaa Thila Lions Head Hans Hass Place Protected Areas 2019 (Total 50 sites) 0 25 50 100 Km &% &% &% Sources: EPA 2019 Alifu Alifu Atoll Emboodhoo Islands Kanduolhi Map version Date: 30/06/2019 &% Orimas Thila Projection: Transverse Mercator (UTM Zone 43 N); 4°0'0"N &% 4°0'0"N Reefs Prepared by: Ministry of Environment, Maldives Fish Head &%Guraidhoo Kanduolhi Horizontal Datum: WGS84; 73°0'0"E 74°0'0"E 73°0'0"E 74°0'0"E 73°0'0"E 74°0'0"E. -

Greater Male Waste-To-Energy Project

wr Report and Recommendation of the President to the Board of Directors Project Number: 51077-003 July 2020 Proposed Loan, Grant, Technical Assistance Grant, and Administration of Loan and Grant Republic of Maldives: Greater Malé Waste-to-Energy Project Distribution of this document is restricted until it has been approved by the Board of Directors. Following such approval, ADB will disclose the document to the public in accordance with ADB’s Access to Information Policy. CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (as of 7 July 2020) Currency unit – Rufiyaa (Rf) Rf1.00 = $0.06 $1.00 = Rf15.40 ABBREVIATIONS 3R – reduce-reuse-recycle ADB – Asian Development Bank AIIB – Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank COVID-19 – coronavirus disease DBO – design–build–operate EIA – environmental impact assessment EIRR – economic internal rate of return EMP – environmental management plan EPA – Environmental Protection Agency FMA – financial management assessment ha – hectare JFJCM Japan Fund for the Joint Crediting Mechanism MOE – Ministry of Environment MOF – Ministry of Finance MW – megawatt O&M – operation and maintenance PAM – project administration manual PMU – project management unit SWM – solid waste management TA – technical assistance tpd – tons per day TRTA – transaction technical assistance WTE – waste-to-energy NOTE In this report, "$" refers to United States dollars. Vice-President Shixin Chen, Operations 1 Director General Kenichi Yokoyama, South Asia Department (SARD) Director Norio Saito, Urban Development and Water Division (SAUW), SARD Team leader Luca Di -

Environmental Impact Assessment of the Development of an Agricultural Center at Mendhoo, Laamu Atoll

ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT OF THE DEVELOPMENT OF AN AGRICULTURAL CENTER AT MENDHOO, LAAMU ATOLL June 2018 Proposed by: Hassan Adil Prepared by: Hassan Shah (EIA P02/2007) Mohamed Umar (EIA T07/2017) Abdul Aleem, (Environmental Consultant) For Water Solutions Pvt. Ltd., Maldives Environmental Impact Assessment of The Development Of An Agricultural Center At Mendhoo, Laamu Atoll Contents 1 DECLARATION OF THE CONSULTANTS ....................................................................... X 2 PROPONENT COMMITMENT AND DECLARATION ................................................... XI 3 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................... 12 3.1 STRUCTURE OF THE EIA ................................................................................................... 12 3.2 AIMS AND OBJECTIVES OF THE EIA .................................................................................. 12 3.3 EIA IMPLEMENTATION ...................................................................................................... 12 3.4 TERMS OF REFERENCE ...................................................................................................... 12 3.5 DESK STUDY REVIEW ....................................................................................................... 12 4 POLICY, LEGAL AND ADMINISTRATIVE FRAMEWORK ......................................... 13 4.1 LAWS AND REGULATIONS ................................................................................................ -

2017 Ubwkitcnia Egukwtcliscnuawk Clwkol Utopir Ubwsih Cswfwt

2017 ubWKitcnia egukwtcliscnuawk clwkOl uTOpir ubWsih csWfwt Local Councils Election 2017 Statistical Report Statistical Report on Local Councils Election 2017 ުބާސިހްސާފަތ 2017 ުބާޚިތްނިއ ެގުކަތްލިސްނުއަކ ްލަކޯލ © ©Elections Commission ްނަޝިމޮކ ްސްނަޝްކެލިއ Published by: :ީރުކުޢިއާޝ Elections Commission ްނަޝިމޮކ ްސްނަޝްކެލިއ Elections Co-ordination and Planning Division ްނަޜިވިޑ ގްނިނޭލްޕ ްޑްނެއ ްނަޝޭނިޑޯކ ްސްނަޝްކެލިއ Planning, Statistics and Archives Section ޕްލޭނިންގ، ސްޓެޓިސްޓިކްސް އެންޑް އާރކައިވްސް ސެކްޝަން Ports Complex, 5th Floor ޕޯޓްސް ކޮމްޕްލެކްސް، 5 ވަނަ ފަންގިފިލާ Hilaalee Magu ުގަމ ީލާލިހ Male’, 20307 މާލެ، 70307 Tel: (+960) 3322241 / (+960) 3004453 ފޯން: 3322241)+960(، 3000053)+060( Fax: (+960) 3323997 Website: www.elections.gov.mv )+960(332997 :ްސްކެފ Email: [email protected] www.elections.gov.mv :ްޓިއަސްބެވ [email protected] :ްލިއެމީއ 1 Secretariat of Elections Commission ާރާދިއ ެގުނަޝިމޮކ ްސްނަޝްކެލިއ Secretariat of Elections Commission ާރާދިއ ެގުނަޝިމޮކ ްސްނަޝްކެލިއ Statistical Report on Local Councils Election 2017 ުބާސިހްސާފަތ 2017 ުބާޚިތްނިއ ެގުކަތްލިސްނުއަކ ްލަކޯލ ްފަރާޢަތ މިރިޕޯޓަކީ، ދިވެހިރާއްޖޭގެ އިދާރީ ދާއިރާތައް ލާމަރުކަޒީ އުސޫލުން ހިންގުމުގެ ޤާނޫނުގެ ދަށުން ބޭއްވުނު ލޯކަލް ކައުންސިލްތަކުގެ އިންތިޚާބު 7102 ގެ ތަފާސް ހިސާބުތަކުގެ .ެވެއުހަވުދ ުރިހިނޮހ ީވ 10 ިއެމ 7102 ީނަވިއަފާވްއާބ ްނުލުޓޯވ ެގުރުބ ަމަތަރުފ ެގުބާޚިތްނިއިމ .ެވެކެޓޯޕިރ ާވިއަފިވެލާވަލުކެއ ްށޮކާނިބ ްށަޗްއަމ ީނަވިއަފިވެދްނެގ ްށަޔިރުކ ްއަތްތަކްއަސަމ ެގ 7102 ުބާޚިތްނިއ ެގުކަތްލިސްނުއަކ ްލަކޯލ ިއަގީލައ ެގާބިރުޖަތ ުނުބިލ ްނުކަތުބާޚިތްނިއ ެގުކަތްލިސްނުއަކ