INFORMATION to USERS This Manuscript Has Been Reproduced

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dreams of a Wood Sprite

DREAMS OF A WOOD SPRITE Gideon Lester talks to director and choreographer Martha Clarke about flying, animals, and A Midsummer Night's Dream. Gideon Lester: A Midsummer Night's Dream is the first Shakespeare that you've directed. When Robert Woodruff approached you to direct at the A.R.T., why did you suggest this play? Martha Clarke: For years I've known that if ever I were to tackle Shakespeare, this would be the play. It's the only one I instinctively felt I would understand, being a bit of a wood sprite. G.L.: How are you a wood sprite? M.C.: You're not supposed to ask those questions. Let's just say that I understand stories of love, transformation, and projecting one's amorous baggage onto someone else. G.L.: So the play has been on your mind for a long time. M.C.: If you can call this a mind! When I was fourteen I played Puck in high school and I still remember great chunks of the text. G.L.: Before rehearsals began you spent a week working with four actors and a vocal coach, Deborah Hecht. You remarked afterwards that the process had made the prospect of staging the play less daunting to you. What did you mean? M.C.: Deb investigates text in the same way that I explore physicality. She unpacks its rhythm, shape, energy, and phrasing - in a sense turning it into music. Shakespeare's language can be either energized or contained, like movement. Speaking the verse requires the actor to make sounds - tight and small or long and full - just as a dancer creates a physical gesture. -

Martha Graham Dance Company Presents NEW@Graham with Maxine Doyle and Bobbi Jene Smith December 18–19, 2018

Martha Graham Dance Company Presents NEW@Graham With Maxine Doyle and Bobbi Jene Smith December 18–19, 2018 New York, NY, November 27, 2018 – The Martha Graham Dance Company’s NEW@Graham series offers a look inside the creative process of new works commissioned by the Company. On December 18 and 19, the Company will present a work-in-progress showing of choreographers Maxine Doyle and Bobbi Jene Smith’s collaborative work for the Company, followed by a conversation with the artists. NEW@Graham will take place on Tuesday, December 18, and Wednesday, December 19, at 7pm, at the Martha Graham Studio Theater. Doyle and Smith are using the classic myth of Demeter and Persephone to investigate the natural human preoccupation with death and the underworld, and the role that women play in our understanding of mortality. Titled Deo, the work features an original score by experimental electronic musician Lesley Flanigan. Deo will premiere as part of the Graham Company’s Eve Project season at The Joyce Theater in April 2019. Tickets are $25 (general) and $20 (students) and can be purchased by phone at 212-229-9200, or online at www.marthagraham.org/studioseries. The Martha Graham Studio Theater is located at 55 Bethune Street, 11th floor, in Manhattan. About the Artists Maxine Doyle is an independent choreographer and director. Since 2002 she has been associate director and choreographer for Punchdrunk, for which she has codirected many works including the multi-award-winning Sleep No More (London, Boston, New York, Shanghai) and The Drowned Man. Her work for theater and opera includes Evening at the Talk House (NT) and The Cunning Little Vixen (Glyndebourne). -

ADF-Timeline.Pdf

Timeline 1934 • ADF, then known as the Bennington School of Dance, is founded at Bennington College in Bennington, Vermont. The first six-week session attracts 103 students (68 of whom were dance teachers) from 26 states, the District of Columbia, Canada and Spain. Their ages range from 15 to 49. • Martha Hill and Mary Josephine Shelly are Co-Directors. Martha Graham, Doris Humphrey, Charles Weidman, and Hanya Holm, also known as "The Big Four,” are recruited to be faculty. They each teach for a week in succession. 1935 • Martha Graham premieres Panorama with Alexander Calder mobiles (his first dance collaboration). • Doris Humphrey premieres New Dance. • The "Big Four" overlap teaching during the six weeks. 1936 • Betty Ford (Elizabeth Bloomer) is a student. • Humphrey completes her New Dance Trilogy with premiere of With My Red Fires; Weidman creates Quest. • World debut of Lincoln Kirstein's Ballet Caravan. Kirstein delivers lectures on classical ballet. 1937 • Anna Sokolow, José Limón, and Esther Junger are the first Bennington Fellows. • Premieres of Holm's Trend, Limón's Danza de la Muerte, Sokolow's Facade-Esposizione Italiana. • Alwin Nikolais is a student. • Graham premieres two solos. 1938 • Premieres are Graham's American Document, Holm's Dance of Work and Play and Dance Sonata, Humphrey's Passacaglia in C Minor, and Weidman's Opus 51. • Anna Halprin and Alwin Nikolais are students. 1939 • Bennington School of Dance spends summer at Mills College in Oakland, CA. • Merce Cunningham is a student. • Limón premieres 5-part solo, Danza Mexicanas. • John Cage gives concert of percussion music. 1940 • School of Dance returns to Bennington and is incorporated under The School of the Arts to foster relationships with the other arts. -

Miki Orihara Solo Concert

LaGuardia Performing Arts Center Steven Hitt...Artistic Producing Director Handan Ozbilgin...Associate Director/Artistic Director Rough Draft Festival Carmen Griffin...Theatre Operations Manager/Technical Director Toni Foy...Education Outreach Coordinator Isabelle Marsico...Events Coordinator Caryn Campo...Finance Officer LaGuardia Performing Arts Center Mariah Sanchez...House Manager Scott Davis...Line Producer Juan Zapata...Graphic Designer Luisa Fer Alarcon...Video Editor/Designer Dayana Sanchez...Marketing Coordinator MIKI ORIHARA SOLO CONCERT Production Staff Patrick Anthony Surillo...Resident Stage Manager Cassandra Lynch...Props Master Hollis Duggans…Production Staff Works of American and Japanese Modern Dance Pioneers Winter Muniz…Production Staff Piano by Nora Izumi Bartosik Technical Staff Glenn Wilson...Stage Manager/Assistant Technical Director Melody Beal...Lighting Designer Alex Desir...Master Electrician Ronn Thomas...Sound Engineer Miki Orihara Marland Harrison...Technician Denton Bailey...Technician Giovanni Perez...Technician House Staff Marissa Bacchus Jason Berrera Julio Chabla Rachel Faria Anne Husmann Emily Johnson Martha Graham Doris Humphrey Rebecca Shrestha LaGuardia Community College Dr. Gail O. Mellow...President Dr. Paul Arcario...Provost and Senior Vice President 31-10 Thomson Avenue Long Island City, 11101 Seiko Takata Konami Ishii Yuriko Upper left: Martha Graham in Lamentation(1930) Photo by Soichi Sunami, courtesy of The Sunami Family. Upper middle: Miki Orihara, Photo by Tokio Kuniyoshi. Upper right: Doris Humphrey photo by Soichi Sunami , courtesy of the Sunami Family. Lower left: Seiko Takata(1938) in Mother Photo courtesy of Nanako Yamada. Lower middle: Konami Ishii in Koushou (1938) Photo courtesy of Noriko Sato. Lower right: Yuriko in The Cry (1963) Photo courtesy of the Kikuchi Family. WWW.LPAC.NYC RESONANCE III “Onko chishin” – is a Japanese expression describing an attempt to discover new things by studying the past. -

2016 Scripps/ADF Award

HONORARY CHAIRPERSONS Mrs. Laura Bush Mrs. Hillary Rodham Clinton Mrs. George Bush Mrs. Nancy Reagan Mrs. Rosalynn Carter Mrs. Betty Ford (1918–2011) BOARD OF DIRECTORS Allen D. Roses, M.D., Chairman Charles L. Reinhart, President, Director Emeritus Curt C. Myers, Secretary/Treasurer Jennings Brody PRESS CONTACT Mimi Bull National Press Representative: Lisa Labrado Rebecca B. Elvin Richard E. Feldman, Esq. [email protected] James Frazier, Ed.D. Jenny Blackwelder Grant Direct: 646-214-5812/Mobile: 917-399-5120 Dave Hurlbert Nancy McKaig Jodee Nimerichter North Carolina Press Representative: Sarah Tondu Adam Reinhart, Ph.D. [email protected] Arthur H. Rogers III Ted Rotante Office: 919-684-6402/Mobile: 919-270-9100 Judith Sagan Russell Savre FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE 2016 SAMUEL H. SCRIPPS/AMERICAN DANCE FESTIVAL AWARD PRESENTED TO LAR LUBOVITCH Durham, NC, January 19, 2016—The American Dance Festival (ADF) will present the 2016 Samuel H. Scripps/American Dance Festival Award for lifetime achievement to Artistic Director and choreographer, Lar Lubovitch. Established in 1981 by Samuel H. Scripps, the annual award honors choreographers who have dedicated their lives and talent to the creation of modern dance. Mr. Lubovitch’s work, acclaimed throughout the world, is renowned for its musicality, emotional style, highly technical choreography, and deeply humanistic voice. The $50,000 award will be presented to Mr. Lubovitch in a brief ceremony on Monday, July 11th at 7:00pm, prior to Lar ADVISORY COMMITTEE Lubovitch Dance Company’s performance at the Durham Performing Arts Center. Robby Barnett Brenda Brodie Martha Clarke “We are exceptionally delighted to honor Lar Lubovitch with this award. -

Fax Coversheet

1111 amberamber trail, madison, trail, ct 06443 madison, ct 0 6 4 4203 3 668 -3153 2 mobile 0 3 2036 6245 8 -3175- 3153 ph/fax [email protected] LIGHTING DESIGNER UNITED SCENIC ARTISTS, LOCAL 829 AGENT: RUSS ROSENSWEIG SUMMIT ENTERTAINMENT 203 453-0188 [email protected] CURRENT ACADEMIC APPOINTMENT PROFESSOR AND CO-CHAIR, DESIGN DEPARTMENT, YALE SCHOOL OF DRAMA NOMINATIONS/AWARDS AMERICAN THEATRE WING, BAY AREA CRITICS CIRCLE, DALLAS THEATER CRITICS FORUM, DRAMA DESK, HELEN HAYES, HENRY HEWES DESIGN, LUCILLE LORTEL AND OUTER CRITICS CIRCLE PRODUCTIONS 2019 OLD GLOBE ROMEO AND JULIET San Diego BY WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE BARRY EDELSTEIN, DIR. OLD GLOBE AS YOU LIKE IT San Diego BY WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE JESSICA STONE, DIR. MARK TAPER FORUM HAPPY DAYS BY SAMUEL BECKETT JAMES BUNDY, DIR. YALE REPERTORY THEATRE GOOD FAITH BY KAREN HARTMAN KENNY LEON, DIR. 2018 LYRIC OPERA OF KANSAS CITY MADAME BUTTERFLY BY GIACOMO PUCCINI RON DANIELS, DIR. HARTFORD STAGE COMPANY HENRY V BY WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE ELIZABETH WILLIAMSON, DIR. ARENA STAGE AT THE MEAD CENTER TURN ME LOOSE KREEGER THEATRE BY GETCHEN LAW Washington, DC JOHN GOULD RUBIN, DIR. OLD GLOBE MUCH ADO ABOUT NOTHING San Diego BY WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE KATHLEEN MARSHALL, DIR. WESTPORT COUNTRY PLAYHOUSE FLYIN’ WEST BY PEARL CLEAGE SERET SCOTT, DIR. AMERICAN REPERTORY THEATRE THE WHITE CARD BY CLAUDIA RANKINE DIANE PAULUS, DIR. 2017 YALE REPERTORY THEATRE NATIVE SON BY NAMBI KELLEY SERET SCOTT, DIR. MAGIC THEATRE THE EVA TRILOGY San Francisco BY BARBARA HAMMOND ⚫ Page 1 11 amber trail, madison, ct 0 6 4 4 3 2 0 3 6 6 8 - 3153 11 amber trail, madison, ct 06443 203 668-3153 mobile 203 245-3175 ph/fax [email protected] LORETTA GRECO, DIR. -

Here He Trained in Jazz, Salsa and African Dance

ABOUT THE CHOCOLATE FACTORY The Chocolate Factory Theater exists to encourage and support artists in their process of inquiry. We engage specifically with a community of artists who challenge themselves and, in doing so, challenge us. We believe that by supporting the labor of artists and the public presentation of their work, we contribute to elevating New York City as a thriving and more equitable wellspring of ideas. SAVE THE DATE! The Chocolate Factory embraces artistic practice as an integral part 15th Annual Taste of LIC - June 10, 2020 of the artist’s whole life, an essential component of the life of our community and a key element of a larger national and international 2019/2020 SEASON artistic dialogue. As such, we host artists as our equal partners with shared autonomy, trust and appreciation. While we seek to make big Justin Cabrillos - as of it ideas and extended relationships possible, we commit to working at September 2-7, 2019 a small, intimate and personal scale, with few artistic compromises or boundaries. Maria Bauman-Morales / MBDance - (re)Source co-presented with BAAD! We achieve all of this by creating a vessel for artistic experimentation September 25-28, 2019 through a residency package serving the whole artist - salary, space, responsive and flexible support for the development of new Antonio Ramos and the Gang Bangers - El pueblo de los Olvidados work from inspiration to presentation. co-presented with Abrons Arts Center October 2-12, 2019 MAJOR SUPPORTERS: Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, The Barbara Kristen Kosmas -

Alan Johnston Petition

ALAN JOHNSTON PETITION BBC News website users around the world have written in their thousands to demand the release of BBC Gaza correspondent Alan Johnston. An online petition was started on Monday, 2 April. It said: “We, the undersigned, demand the immediate release of BBC Gaza correspondent Alan Johnston. We ask again that everyone with influence on this situation increase their efforts, to ensure that Alan is freed quickly and unharmed.” More than 8,000 people responded in the first few days. In total, more than 69,000 have signed. The latest names to be added are published below. A Brook Ontario, Canada A. Colley Cardiff, UK A Butcher Los Gatos, USA A. Giesswein New Jersey, USA A Capleton Cardiff, UK A. Homan Sheffield, UK A Crockett Looe, Cornwall A. Ockwell Edinburgh, UK A Farnaby Middlesbrough A. Parker Johannesburg, South England Africa A Fawcett Cardiff, Wales A. Saffour London, UK A Foster Macclesfield England A. Yusif Sizalo Accra, GHANA A Kennedy London, UK A.J. Janschewitz Brooklyn, New A KUMAR Birmingham, UK York, USA A Mc Sevenoaks UK A.J. Whitfield sydney, Australia A Norman Brighton UK A.M. Majetich hicksville, usa A P Jurisic Pittsburgh, USA A.M.Sall St-Louis, Senegal a pritchard Treforest Glamorgan Aaliya Naqvi-Hai Belmont, USA A R Pickard Pontypridd, Wales Aaron Ambrose NY, NY US a skouros uk Aaron Bennett Berkeley, CA U.S.A A Stevenson Aberdeenshire Aaron Beth'el Byron Bay, Australia A Tudor Dartington, UK Aaron Cullen Aberdeen A Whiting Aberdeen, Scotland Aaron Davies London, UK Aaron Dublin, Ireland. Abraham Sont Lanark(area)- Aaron H. -

RBF Program 4-16 2

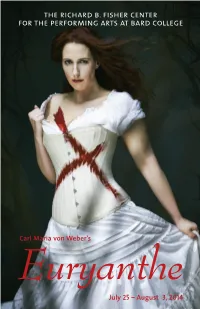

the richard b. fisher center for the performing arts at bard college Carl Maria von Weber’s Euryanthe July 25 – August 3, 2014 About The Richard B. Fisher Center for the Performing Arts at Bard College The Richard B. Fisher Center for the Performing Arts, an environment for world-class artistic presentation in the Hudson Valley, was designed by Frank Gehry and opened in 2003. Risk-taking performances and provocative programs take place in the 800-seat Sosnoff Theater, a proscenium-arch space, and in the 220-seat Theater Two, which fea- tures a flexible seating configuration. The Center is home to Bard College’s Theater & Performance and Dance Programs, and host to two annual summer festivals: SummerScape, which offers opera, dance, theater, film, and cabaret; and the Bard Music Festival, which celebrates its 25th year in August with “Schubert and His World.” The Center bears the name of the late Richard B. Fisher, the former chair of Bard College’s Board of Trustees. This magnificent building is a tribute to his vision and leadership. The outstanding arts events that take place here would not be possible without the con- tributions made by the Friends of the Fisher Center. We are grateful for their support and welcome all donations. The 2014 SummerScape season is made possible in part through the generous support of Jeanne Donovan Fisher, the Martin and Toni Sosnoff Foundation, the Board of The Richard B. Fisher Center for the Performing Arts at Bard College, the Board of the Bard Music Festival, and the Friends of the Fisher Center, as well as grants from The Andrew W. -

In Celebration of Anna Sokolow's Centennial 1910-2010 from The

V olume V No. 1 September 2010 From the Dance Notation Bureau e c INSIDE THIS ISSUE n a D n e In Celebration of Anna a • c m ri o e Sokolow’s Centennial c s m A 1910-2010 Ba rd m fo fro d rs Ra e c © n o a t d o h h t P i . e w g l Dance Notation Bureau Library e l a l s Monday - Friday 10am - 6pm r a Co e t h Advance Notification by Phone/Email u re c i t Recommended n c i e n w n o l Co o 111 John Street, Suite 704 t k a o l New York, NY 10038 S a v a i t Phone: 212/571-7011 n s n e Fax: 212/571-7012 A F Email: [email protected] Website: www.dancenotation.org In Celebration of Anna Sokolow’s Centennial 1910-2010 by Hannah Kosstrin Library News is published twice a year in New York 2010 marks the centennial of choreographer Anna Sokolow’s birth. Sokolow, who lived from 1910-2000 and was known for her fierce dedication to concert Editor: dance as an art form, her insatiable search for truth in performance, and her Lucy Venable career-long fight for dance for social change, believed strongly in the importance of Labanotation for the preservation and dissemination of her choreography. Her Director of Library Services: association with the Dance Notation Bureau began in the 1960s, and continues Mei-Chen Lu through the licensing and recording of her work. -

Pilobolus Dance Theater

Nadirah Zakariya Nadirah Presented by Dance Affiliates and Annenberg Center Live PILOBOLUS DANCE THEATER Executive Producer Itamar Kubovy Artistic Directors Robby Barnett and Michael Tracy Associate Artistic Directors Renée Jaworski and Matt Kent Dancers: Shawn Fitzgerald Ahern, Antoine Banks-Sullivan, Krystal Butler, Benjamin Coalte, Jordan Kriston, Derion Loman, Mike Tyus Dance Captain Shawn Fitzgerald Ahern Production Manager Kristin Helfrich Production Stage Manager Shelby Sonnenberg Lighting Supervisor Mike Faba Video Technician Molly Schleicher Éminence Grise Neil Peter Jampolis Stage Ops Eric Taylor PROGRAM On The Nature of Things The Transformation Automaton // Intermission // [esc] Day Two //////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////////// Thursday, May 7 at 7:30 PM Friday, May 8 at 8 PM Saturday, May 9 at 3 PM and 8 PM Sunday, May 10 at 3 PM Zellerbach Theatre 30 // ANNENBERG CENTER LIVE PROGRAM NOTES Pilobolus Is A Fungus Edited by: Oriel Pe’er and Paula Salhany Score by: Keith Kenniff On The Nature Of Things (2014) Created by: Robby Barnett, Renée Jaworski, Matt Kent, and Itamar Kubovy in collaboration with Shawn Fitzgerald Ahern, Benjamin Coalter, Matt Del Rosario, Eriko Jimbo, Jordan Kriston, Jun Kuribayashi, Derion Loman, Nile Russell, and Mike Tyus Performed by: Shawn Fitzgerald Ahern, Jordan Kriston and Mike Tyus Music: Vivaldi; Michelle DiBucci and Edward Bilous Mezzo Soprano: Clare McNamara Violin Solo: Krystof Witek Lighting and Set Design: Neil Peter Jampolis On The Nature Of Things was commissioned by The Dau Family Foundation in honor of Elizabeth Hoffman and David Mechlin; Treacy and Darcy Beyer; The American Dance Festival with support from the SHS Foundation and the Charles L. and Stephanie Reinhart Fund; and by the National Endowment for the Arts, which believes a great nation deserves great art. -

Martha Graham Dance Company

CAL PERFORMANCES PRESENTS Friday, January 31, 2014, 8pm Saturday, February 1, 2014, 8pm Zellerbach Hall Martha Graham Dance Company Artistic Director Janet Eilber Executive Director LaRue Allen The Company Tadej Brdnik Katherine Crockett Carrie Ellmore-Tallitsch Maurizio Nardi Miki Orihara Blakeley White-McGuire PeiJu Chien-Pott Lloyd Knight Mariya Dashkina Maddux Ben Schultz Xiaochuan Xie Natasha Diamond-Walker Abdiel Jacobsen Lloyd Mayor Laura Newman Lorenzo Pagano Ying Xin Tamisha Guy Music Director & Conductor Aaron Sherber Senior Artistic Associate Denise Vale Members of Berkeley Symphony Major support for the Martha Graham Dance Company is provided by The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, the National Endowment for the Arts, the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs, and the New York State Council on the Arts. The Artists employed in this production are members of the American Guild of Musical Artists, AFL-CIO. Copyright to all dances held by the Martha Graham Center of Contemporary Dance. All rights reserved. Cal Performances’ 2013–2014 season is sponsored by Wells Fargo. CAL PERFORMANCES 3 PROGRAM PROGRAM Martha Graham Dance Company program Appalachian Spring intermission Cave of the Heart Maple Leaf Rag John Deane John Program and artists are subject to change. Tadej Brdnik and Miki Orihara in Appalachian Spring cast — january 31 • The Bride Blakeley White-McGuire The Husbandman Abdiel Jacobsen The Preacher Maurizio Nardi PROGRAM The Pioneering Woman Natasha Diamond-Walker The Followers PeiJu Chien-Pott, Tamisha Guy, Lauren Newman, Ying Xin Appalachian Spring cast — february 1 Choreography and Costumes Martha Graham † Music Aaron Copland The Bride Mariya Dashkina Maddux Set Isamu Noguchi The Husbandman Lloyd Mayor Original Lighting Jean Rosenthal, adapted by Beverly Emmons The Preacher Lloyd Knight The Pioneering Woman Natasha Diamond-Walker Première October 30, 1944, Coolidge Auditorium, The Followers PeiJu Chien-Pott, Tamisha Guy, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.