Rural Tuscany After the Exodus (1970-1985)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fratelli-Wine-Full-October-1.Pdf

SIGNATURE COCKTAILS Luna Don Julio Blanco, Aperol, Passionfruit, Fresh Lime Juice 18 Pear of Brothers Ketel One Citroen, Pear Juice, Agave, Fresh Lemon Juice 16 Sorelle Absolut Ruby Red, Grapefruit Juice, St. Elder, Prosecco, Aperol, Lemon Juice 16 Poker Face Hendricks, St. Elder, Blackberry Puree, Ginger Beer, Fresh Lime Juice 17 Famous Espresso Martini Absolut Vanilla, Bailey’s, Kahlua, Frangelico, Disaronno, Espresso, Raw Sugar & Cocoa Rim 19 Uncle Nino Michter’s Bourbon, Amaro Nonino, Orange Juice, Agave, Cinnamon 17 Fantasma Ghost Tequila, Raspberries, Egg White, Pomegranate Juice, Lemon Juice 16 Tito’s Doli Tito’s infused pineapple nectar, luxardo cherry 17 Ciao Bella (Old Fashioned) Maker’s Mark, Chia Tea Syrup, Vanilla Bitters 17 Fratelli’s Sangria Martell VS, Combier Peach, Cointreau, Apple Pucker, red or white wine 18 BEER DRAFT BOTTLE Night Shift Brewing ‘Santilli’ IPA 9 Stella 9 Allagash Belgian Ale 9 Corona 9 Sam Adams Seasonal 9 Heineken 9 Peroni 9 Downeast Cider 9 Bud Light 8 Coors Light 8 Buckler N.A. 8 WINES BY THE GLASS SPARKLING Gl Btl N.V. Gambino, Prosecco, Veneto, Italy 16 64 N.V. Ruffino, Rose, Veneto, Italy 15 60 N.V. Veuve Clicquot, Brut, Reims, France 29 116 WHITES 2018 Chardonnay, Tormaresca, Puglia, Italy 17 68 2015 Chardonnay, Tom Gore, Sonoma, California 14 56 2016 Chardonnay, Jordan Winery, Russian River Valley, California 21 84 2017 Falanghina, Vesevo, Campania, Italy 15 60 2018 Gavi di Gavi, Beni di Batasiolo, Piemonte, Italy 14 56 2018 Pinot Grigio, Villa Marchese, Friuli, Italy 14 56 2017 Riesling, Kung -

Siena for Foodies: Local Produce and Food Fairs

Siena for foodies: local produce and food fairs The Siena area is a land of soft valleys that have made Tuscany famous worldwide with their wines and food products. It is home to all the villages and land within the “Siena Province” political boundaries. In this guide you’ll find some tips about the best local produce and food fairs along Siena’s wine and food routes. SIENA SWEET SIENA Vino Nobile di Montepulciano is one of the oldest A wines in Italy. It’s a flavourful, dry, red wine with the Denomina- Panforte is a traditional Christmas sweet, low and zione di Origine Controllata e Garantita (DOCG) status compact, and made from honey, nuts, almonds, hazelnuts, produced in the vineyards surrounding the town. Other food spices and candied fruit. Cavallucci and Ricciarelli products include pecorino cheese, marmalades, Chianina beef are two delicious local biscuits. Cavallucci have a soft and Cinta Senese salami. texture and contain nuts and spices, while Ricciarelli are made with almond flour and are covered with vanilla icing sugar. If you are in the Siena area around All Saints’ day, you will find almost everywhere a cake called “Pan co’ Santi”, a fluffy sweet bread flavoured with walnuts and raisins. Another delicious dessert that you must taste is the Tuscan pine nuts cake or Pinolata senese. E ON THE CHIANTI CLASSICO ROAD B AROUND THE MERSE VALLEY The Chianti Classico territory with its hilly countryside lies in the very heart of Tuscany between Siena and The Merse Valley is an oasis of silent forests full of histori- Florence. -

Veneto 10/38 Lucciola Organic Pinot Grigio 2018

ITALIAN WHITES SANTI SORTESELE PINOT GRIGIO 2019 – VENETO 10/38 LUCCIOLA ORGANIC PINOT GRIGIO 2018 - ALTO ADIGE 9/34 ITALIAN REDS ABBAZIA DI NOVACELLA PINOT GRIGIO 2017 – VENETO 45 LA SERENA BRUNELLO DI MONTALCINO 2010 - TUSCANY 144 VILLA SPARINA GAVI 2018 — PIEDMONT 34 PAOLO CONTERNO BAROLO 2011 - PIEDMONT 112 SERIO E BATISTA BORGOGNO, CANNUBI BAROLO 2015 - PIEDMONT 78 CHAMPAGNE & SPARKLING CAMPASS BARBERA D’ ALBA 2016 - PIEDMONT 51 NTONIOLO ASTELLE ATTINARA IEDMONT MARTINI & ROSSI ASTI NV – ITALY (187ML) 9 A C G 2013 - P 98 AOLO CAVINO ANGHE EBBIOLO IEDMONT DA LUCA PROSECCO NV – ITALY 9/34 P S L N 2017 - P 49 AOLO CAVINO INO OSSO IEDMONT FERRARI BRUT - ITALY (750ML) 56 P S V R 2018 - P 38 SANTI “SOLANE” VALPOLICELLA CLASSICO SUPERIORE 2015 – VENETO 42 LAURENT PERRIER BRUT CHAMPAGNE NV - FRANCE (187 ML) 21 LE RAGOSE AMARONE DELLA VALPOLICELLA 2008 - VENETO 102 CONUNDRUM BLANC DE BLANC 2016 - CA 53 BERTANI AMARONE CLASSICO DELLA VALPOLICELLA 2009 — VENETO 200 POL ROGER EXTRA CUVÉE DE RÉSERVE NV – FRANCE (375 ML) 55 BADIA A COLTIBUONO ORGANIC CHIANTI CLASSICO 2016 - TUSCANY 49 TAITTINGER BRUT CUVEE PRESTIGE NV - CHAMPAGNE, FRANCE 72 ORMANNI CHIANTI CLASSICO 2016 - TUSCANY 45 VUEVE CLIQUOT ROSE NV - CHAMPAGNE, FRANCE 118 CASTELLO DI AMA CHIANTI CLASSICO SAN LORENZO 2014 - TUSCANY 91 DOMAINE DE CHANDON “BLANC DE NOIRS” NV CARNEROS, CA 42 CASTELLO DI BOSSI GRAN SELEZIONE CHIANTI CLASSICO 2016—TUSCANY 13/49 SAUVIGNON BLANC FATTORIA LE PUPILLE “MORELLINO DI SCANSANO” 2015 - TUSCANY 40 LA COLOMBINA BRUNELLO DI MONTALCINO 2010 - TUSCANY 120 DOMAINE -

International Mail Crossing the Italian Peninsula in the Pre-Stamp Period 1815—1852

International Mail crossing the Italian Peninsula in the Pre-Stamp Period 1815—1852 prepared for the Collectors Club of New York, November 14th, 2012 by Thomas Mathà FRPSL This exhibit shows the letter mail, the postal rates, the routes, the conventions and markings of foreign countries trans- iting the Roman States in the period from the Congress of Vienna (1815), when Europe was re-organized after the Napoleonic Wars, to the introduction of the postage stamps in Rome in 1852. Subsequently, the letter mail in the Ro- man States changed and new conventions modified also international relations and the mail system. It is mainly mail from and to the South of Italy, Ionian Islands and Malta that followed the route of Rome. PARIS to NAPLES. January 2, 1833 by Royal Courier via Rome. Personal Letter from Louis Philippe, King of France, to Ferdinand II, King of Both Sicilies A. Introduction C. Foreign Mail carried through Roman States A.1 · Routes & Exchange Offices A.2 · Transit Routes C.1 · Roman-Austrian Postal Convention (1815) A.3 · Exchange and Entry Markings C.2 · special Austrian Lloyd Postal Convention (1839) A.4 · General Guidelines C.3 · Franco-Austrian Postal Convention (1843) C.4 · Sardinian-Austrian Postal Convention (1818) B. Mail exchanged between the Old Italian States C.5 · Franco-Sardinian Postal Convention (1817) B.1 · Roman-Austrian Postal Convention (1815) C.6 · Roman-Neapolitan Postal Convention (1816) B.2 · Roman-Tuscan Postal Convention (1823) C.7 · carried by Forwarding Agents B.3 · Tuscan-Sardinian Postal Convention (1822) Thomas Mathà, born in 1972, is a lawyer and lives in Bozen, Italy. -

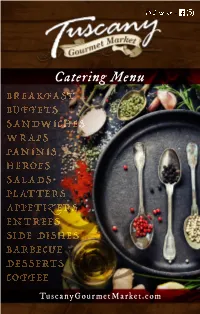

Catering Menu

Catering Menu TuscanyGourmetMarket.com Bring our best to your table. At Tuscany Gourmet Market, we think of you more like family- to us you're not just another customer. We’re here to prepare you and your guests a delicious meal- so, sit back and relax while we do what we do best. Restaurant quality food, mixed with the love & care of your Grandmother’s homecooking. We’ve got just about everything from soup to nuts. That’s because we want you to enjoy an impressive, seamless meal. If choosing your menu seems overwhelming, we’re happy to make suggestions that everyone will love. Planning an Event? Consider us your one-stop-shop for an unforget- table experience. We've got you covered from wait staff to full service Event Coordinating. BREAKFAST Continental Breakfast Assorted Bakery-Fresh Bagels, Assorted Danish, & Muffins. (w/ Gourmet Cream Cheese platter, Butter, & Fruit Preserves.) Fresh Fruit Salad Fresh-Brewed Coffee & Tea, chilled Tropicana Orange Juice. Includes all heavy-duty plasticware. Minimum 10 people Hot Breakfast Buffet Choice of Fresh Scrambled Eggs or Western-Style Egg Fritatta. Includes Belgian Waffles, Home Fries, Bacon, Sausage, Assorted Bakery-Fresh Bagels, Assorted Danish, Muffins (w/ Gourmet Cream Cheese platter, Butter, & Fruit Preserves.) Fresh Fruit Salad Fresh-Brewed Coffee & Tea, chilled Tropicana Orange Juice. Includes all condiments & paper goods. Minimum 10 people Yogurt Parfait French Vanilla Yogurt topped w/ crunchy Granola & Fresh seasonal Berries 3 lbs. - Serves 5 - 10 people 5 lbs. - Serves 10-15 people Visit Us Online @: TuscanyGourmetMarket.com 1 Cold Buffet A la Carte Elegantly arranged platters consist of: • Italian-seasoned Roast Beef • Boar’s Head Ovengold® Turkey Breast • Boar’s Head Deluxe Boiled Ham • Italian Genoa Salami • Sharp Provolone cheese • Imported Swiss cheese • Land O’Lakes American cheese (Garnished with roasted peppers, red onions & beefsteak tomatoes.) Includes: Fresh-baked Hard Rolls, Rye bread, White bread, Whole Wheat bread, Mayonnaise, Mustard, Italian dressing, + Pickle & Olive tray. -

Florenz Und Provinz Florenz

Restaurantempfehlungen der Toskanababys Eine Sammlung aus den vergangenen Jahren, nicht jedes Restaurant ist noch immer an seinem Platz. Florenz und Provinz Florenz Trattoria da Pietro Florenz, Piazza delle Cure [Tel.:+39 55578889] Eine typische Trattoria denke ich mir, schaue auf die mir von einem freundlichen Kellner gereichte Speisekarte und wähle als Vorspeise leckere Ravioli mit Gorgonzola und Ruccola und anschließend ein zartes Rinderfilet in grüner Pfeffersoße. Mineralwasser und Weißwein zum Durstlöschen und Müdewerden. Als Dessert ein Stück Torta della Nonna und einen Caffè. (aus: Reisetagebuch 2001) Enoteca Fuori Porta Florenz, Via Monte alle Croci 10/r [Tel.: +39 0552342483] Internet: http://www.fuoriporta.it Zum Abschluss gibt es ein sehr gutes Abendessen inklusive Weinkauf in der Enoteca Fuori Porta. (aus: Reisetagebuch 1998) Trattoria del Carmine Florenz, Piazza del Carmine 18r, [Tel.: 055 218601] Mittlerweile ist es Zeit für das Abendessen. Südlich des Arnos lädt uns die Trattoria del Carmine ein. Wir bestellen gemischt belegte Brote und Hühnchensalat als Vorspeise und anschließend als ersten Gang Lasagne nach Art des Hauses. Uns bleibt kaum Zeit um uns zu entspannen und still den 2001er Rotwein der Villa Calcinaia aus dem klassischem Anbaugebiet in der Toskana zu genießen, da wird uns als Hauptspeise Schnitzel mit Anchovis und Huhn mit Pesto gereicht. Perfekt wird unsere erste Mahlzeit in Florenz durch ein Stück Torte nach Großmutter-Art sowie einen Espresso. Trattoria Pizzeria Dante Florenz, Piazza Nazario Sauro, [Tel.: 055.293215] Am Abend essen wir in der Trattoria und Pizzeria Dante leckere Spaghetti alla casa, ein Risotto mit Radicchio und Gorgonzola sowie zwei richtig dünne und gutbelegte Pizzen. -

Val D'orcia 1

VAL D’ORCIA Sweet round-shaped hills, changing colour according to the season, low valleys along the Orcia river, parish churches and restored farms here and there, often hiding in a forest of cypresses. Such are the characteristics making the charm of Val d’Orcia incomparable, an extraordinary synthesis between nature, art and deeply rooted traditions. This beautiful area of Tuscany is under the authority of the Val d’Orcia Park, instituted to maintain and develop the heritage of a region to promote its typical produce. The fertile countryside of Val d’Orcia, cultivated with respect and wisdom, produces excellent wines, olive oil and high quality cereals. The landscape is deeply marked by man’s intervention aiming to enrich the natural beauty with sobre religious and civilian works of art. It is difficult to explain with words the serene charm emanating from the lands of Val d’Orcia in the spring, when the hills turn green, in the summer when the yellow colour of sunflowers and wheat fields dominates the area, in the beautiful fragrance of a variety of plants. In the south of Bagno Vignoni, olive groves, vineyards and cultivated fields are replaced by a Mediterranean bushland while in the Mount Amiata area opens out a thick forest of chestnut and beech groves. Mother Nature, especially generous with the Val d’Orcia’s people, did not forget to create thermal springs for rest and care. The Via Francigena goes through Val d'Orcia near the small village of Bagno Vignoni, visited by famous people and pilgrims. Already inhabited in the Etruscan period, the Val d’Orcia keeps architectural vestiges from the Middle Ages and the Renaissance. -

Viva Xpress Logistics (Uk)

VIVA XPRESS LOGISTICS (UK) Tel : +44 1753 210 700 World Xpress Centre, Galleymead Road Fax : +44 1753 210 709 SL3 0EN Colnbrook, Berkshire E-mail : [email protected] UNITED KINGDOM Web : www.vxlnet.co.uk Selection ZONE FULL REPORT Filter : Sort : Group : Code Zone Description ZIP CODES From To Agent IT ITAOD04 IT- 3 Days (Ex LHR) Cities & Suburbs CIVITELLA CESI 01010 - 01010 CELLERE 01010 - 01010 AZIENDA ARCIONE 01010 - 01010 ARLENA DI CASTRO 01010 - 01010 FARNESE 01010 - 01010 LATERA 01010 - 01010 MONTEROMANO 01010 - 01010 ONANO 01010 - 01010 PESCIA ROMANA 01010 - 01010 PIANSANO 01010 - 01010 TESSENNANO 01010 - 01010 VEIANO 01010 - 01010 VILLA S GIOVANNI IN TUSC 01010 - 01010 MUSIGNANO 01011 - 01011 CELLENO 01020 - 01020 CHIA 01020 - 01020 CASTEL CELLESI 01020 - 01020 CASENUOVE 01020 - 01020 GRAFFIGNANO 01020 - 01020 LUBRIANO 01020 - 01020 MUGNANO 01020 - 01020 PROCENO 01020 - 01020 ROCCALVECCE 01020 - 01020 SAN MICHELE IN TEVERINA 01020 - 01020 SERMUGNANO 01020 - 01020 SIPICCIANO 01020 - 01020 TORRE ALFINA 01020 - 01020 TREVIGNANO 01020 - 01020 TREVINANO 01020 - 01020 VETRIOLO 01020 - 01020 ACQUAPENDENTE 01021 - 01021 CIVITA BAGNOREGIO 01022 - 01022 BAGNOREGIO 01022 - 01022 CASTIGLIONE IN TEVERINA 01024 - 01024 GROTTE SANTO STEFANO 01026 - 01026 MAGUGNANO 01026 - 01026 CASTEL S ELIA 01030 - 01030 CALCATA 01030 - 01030 BASSANO ROMANO 01030 - 01030 FALERIA 01030 - 01030 FABBRICA DI ROMA 01034 - 01034 COLLEMORESCO 02010 - 02010 COLLI SUL VELINO 02010 - 02010 CITTAREALE 02010 - 02010 CASTEL S ANGELO 02010 - 02010 CASTEL SANT'ANGELO 02010 -

SWE PIEDMONT Vs TUSCANY BACKGROUNDER

SWE PIEDMONT vs TUSCANY BACKGROUNDER ITALY Italy is a spirited, thriving, ancient enigma that unveils, yet hides, many faces. Invading Phoenicians, Greeks, Cathaginians, as well as native Etruscans and Romans left their imprints as did the Saracens, Visigoths, Normans, Austrian and Germans who succeeded them. As one of the world's top industrial nations, Italy offers a unique marriage of past and present, tradition blended with modern technology -- as exemplified by the Banfi winery and vineyard estate in Montalcino. Italy is 760 miles long and approximately 100 miles wide (150 at its widest point), an area of 116,303 square miles -- the combined area of Georgia and Florida. It is subdivided into 20 regions, and inhabited by more than 60 million people. Italy's climate is temperate, as it is surrounded on three sides by the sea, and protected from icy northern winds by the majestic sweep of alpine ranges. Winters are fairly mild, and summers are pleasant and enjoyable. NORTHWESTERN ITALY The northwest sector of Italy includes the greater part of the arc of the Alps and Apennines, from which the land slopes toward the Po River. The area is divided into five regions: Valle d'Aosta, Piedmont, Liguria, Lombardy and Emilia-Romagna. Like the topography, soil and climate, the types of wine produced in these areas vary considerably from one region to another. This part of Italy is extremely prosperous, since it includes the so-called industrial triangle, made up of the cities of Milan, Turin and Genoa, as well as the rich agricultural lands of the Po River and its tributaries. -

American Born Iris Origo Saw Italythrough a Stage Of

LA FOCE distance from the borgo: 35km American born Iris Origo saw Italy through a stage of incredible change, from Savoy monarchy through Mussolini and the Second World War, from the centuries-old peasant farming system to Italy’s much-belated industrialization. She left a collection of literature, a personal account of German occupation and thrilling escape during wartime, a legacy of conscientious farming in a land hard to conquer, and a beautiful, mani- cured estate in the picturesque Val d’Orcia. Her house, La Foce, sits on one of the most comely and typically Tuscan roads in the area, its winding grade marked by even cypresses. A visit to La Foce is an opportunity not only to experience the famous estate and gardens, but to learn about Iris Origo who was an enormously intriguing individual, as well as her circle of expatriates which included Bernard Berenson and Edith Wharton among others, and about the evolution of Tuscany as we know it today. New York-born Origo’s early years, following the loss of her father, were spent traversing the world with her mother before establishing a base at the Villa Medici in Fiesole, outside of Florence. There she grew up among her mother’s circle of wealthy English expatriates. In the 1920s she married Italian Antonio Origo and escaped to a very different world of their choosing, a dilapidated farm on a vast landholding south of Siena. They transformed the dry valley into a working estate with rebuilt farmhouses and a school. They also rebuilt the villa at La Foce and its gardens. -

Guida-Inventario Dell'archivio Di Stato

MINIS TERO PER I BENI CULTURALI E AM BIENTALI PU B BLICAZIONI DEGLI ARCHIVI DI STATO XCII ARCHIVIO DI STATO DI SIENA GUIDA-INVENTARIO DELL'ARCHIVIO DI STATO VOLUME TERZO ROMA 1977 SOMMARIO Pag. Prefazione VII Archivio Notarile l Vicariati 77 Feudi 93 Archivi privati 105 Bandini Policarpo 106 Bologna-Buonsignori-Placidi 108 Borghesi 140 Brancadori 111 Brichieri-Colombi 113 Busacca Raffaele 115 Canonica (la) 116 Nerazzini Cesare 118 Pannocchieschi-D'Elci 120 Petrucci 140 Piccolomini-Clementini 123 Piccolomini-Clementini-Adami 128 Piccolomini-Naldi-Bandini 131 Piccolomini (Consorteria) 134 Sergardi-Biringucci 137 Spannocchi 141 Tolomei 143 Useppi 146 Venturi-Gallerani 148 Particolari 151 Famiglie senesi 152 Famiglie forestiere 161 PR EFAZIONE Nella introduzione al primo volume della guida-inventario dell'Archivio di Stato di Siena furono esposti gli intenti con i quali ci si accinse alla pub blicazione di quell'importante mezzo di corredo che consistevano nel valorizzare il materiale documentario di ciascun fo ndo archivistico per facilitare agli stu diosi la via della ricerca storica. Il caloroso e benevolo accoglimento riservato dagli interessati dice chiaramente quanto fe lice sia stata l'iniziativa e quanto brillanti siano stati i risultati raggiunti, che si sono palesati anche maggiori di quelli previsti. Infa tti la valorizzazione del materiale, oltre all'ordinamento ed alla inventariazione degli atti, presupponeva anche lo studio accurato delle ori gini e delle competenze dell'ufficio o dell'ente che quegli atti aveva prodotto. Per cui, essendo stati illustrati nei primi due volumi 1 ottanta fondi appartenenti alle più importanti magistrature dello Stato, insieme alla storia di ogni singolo ufficio è emersa in breve sintesi anche la storia del popolo senese. -

Mercatale Val Di Pesa

Monte Nisa The villa, the surroundings. 2 The Villa: The surroundings: Website: https://www.montenisa.com/ ● short story ● around the villa ● the position ● Florence ● contacts ● Siena ● photo 3 The villa Monte Nisa Monte Nisa is a villa overlooking the Chianti hills of San Casciano in Val di Pesa. This is a holiday home consisting of two apartments that can accommodate 6 people each for a total of 12 people, No meals or other professional services are provided, just a whiff of a tourist destination. It is possible to rent the entire property for exclusive use - "Total Nisa" or just one apartment - "Terra Nisa" for the ground floor apartment, "Sopra Nisa" for the first floor apartment. By renting the entire structure you have the exclusive use of the swimming pool and the park, while if you rent an apartment the pool and park are shared with the guests of the other apartment. 5 La storia Monte Nisa is a villa built in 1934 on the top of a hill in Tuscany, in the Chianti Classico wine production area. Its quiet, panoramic and sunny position was chosen with great care and passion by the first owner, named Manetti, and the original toponym of "Villa Manetto" derived from his name. Manetti designed the villa to make it his "buen retiro" following and personally directing the construction work and taking care of every little detail. Subsequently the heirs sold the villa which since then experienced a troubled period, becoming from time to time a summer colony, recreational club, warehouse and even military command during the Second World War, suffering damage due to cannon fire.