Toccata Classics TOCC0176 Notes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ED024693.Pdf

DO CUMEN T R UM? ED 024 693 24 TE 001 061 By-Bogard. Travis. Ed. International Conference on Theatre Education and Development: A Report on the Conference Sponsored by AETA (State Department. Washington. D.C.. June 14-18. 1967). Spons Agency- American Educational Theatre Association. Washington. D.C.;Office of Education (DHEW). Washington. D.C. Bureau of Research. Bureau No- BR- 7-0783 Pub Date Aug 68 Grant- OEG- 1- 7-070783-1713 Note- I28p. Available from- AETA Executive Office. John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts. 726 Jackson Place. N.V. Washington. D.C. (HC-$2.00). Journal Cit- Educational Theatre Journal; v20 n2A Aug 1968 Special Issue EDRS Price MF-$0.75 HC Not Available from EDRS. Descriptors-Acoustical Environment. Acting. Audiences. Auditoriums. Creative Dramatics. Drama. Dramatic Play. Dramatics. Education. Facilities. Fine Arts. Playwriting, Production Techniques. Speech. Speech Education. Theater Arts. Theaters The conference reported here was attended by educators and theater professionals from 24 countries, grouped into five discussion sections. Summaries of the proceedings of the discussion groups. each followed by postscripts by individual participants who wished to amplify portions of the summary. are presented. The discussion groups and the editors of their discussions are:"Training Theatre Personnel,Ralph Allen;"Theatre and Its Developing Audience," Francis Hodge; "Developing and Improving Artistic Leadership." Brooks McNamara; "Theatre in the Education Process." 0. G. Brockett; and "Improving Design for the Technical Function. Scenography. Structure and Function," Richard Schechner. A final section, "Soliloquies and Passages-at-Arms." containsselectedtranscriptions from audio tapes of portions of the conference. (JS) Educational Theatrejourna 1. -

Juilliard String Quartet Areta Zhulla and Ronald Copes, Violins Roger Tapping, Viola Astrid Schween, Cello

Thursday Evening, December 12, 2019, at 7:30 The Juilliard School presents Juilliard String Quartet Areta Zhulla and Ronald Copes, Violins Roger Tapping, Viola Astrid Schween, Cello LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN (1770–1827) String Quartet No. 1 in F major, Op. 18, No. 1 Allegro con brio Adagio affettuoso ed appassionato Scherzo: Allegro molto Allegro GYÖRGY KURTÁG (b. 1926) 6 Moments musicaux, Op. 44 Invocatio (Un fragment) Footfalls (… as if someone were coming) Capriccio In memoriam Sebok˝ György Rappel des oiseaux ... (Étude pour les harmoniques) Les adieux (in Janáceks˘ Manier) Intermission BEETHOVEN Quartet No. 14 in C-sharp minor, Op. 131 Adagio ma non troppo e molto espressivo Allegro molto vivace Allegro moderato—Adagio Andante, ma non troppo e molto cantabile Presto Adagio quasi un poco andante Allegro Performance time: approximately 1 hour and 45 minutes, including an intermission The taking of photographs and the use of recording equipment are not permitted in this auditorium. Information regarding gifts to the school may be obtained from the Juilliard School Development Office, 60 Lincoln Center Plaza, New York, NY 10023-6588; (212) 799-5000, ext. 278 (juilliard.edu/giving). Alice Tully Hall Please make certain that all electronic devices are turned off during the performance. Notes on the Program published, in 1801. The D-major quartet (Op. 18, No. 3) was the first to be written; the By James M. Keller F-major (No. 1) and G-major (No. 2) followed, probably in that order; and the A major String Quartet No. 1 in F major, Op. 18, (No. 5), C minor (No. -

TOCC 0230 Farkas Orch Music Vol. 4 Booklet Copy

FERENC FARKAS: WORKS FOR FLUTE AND CHAMBER ORCHESTRA by László Gombos Te surname Farkas (which means ‘wolf’) is not an uncommon one in Hungary. Tat is why a casual outsider might have thought that in the second half of the twentieth century there were several composers called Ferenc Farkas at work in Budapest at the same time. One of them was a successful composer of operas who was also represented by oratorios and orchestral and chamber music in a modern idiom, heard in the programmes of the major concert-halls. Another was a popular author of operettas, whose works, notching up hundreds of performances, were attended by a public entirely diferent from that of his namesake. A third composer conjured up the music of old times through various arrangements of early Hungarian dances and melodies and also found time to write incidental music to a number of flms, plays and radio plays. Hundreds of thousands of people knew a Ferenc Farkas who composed easy pieces for children, youth orchestras and amateur choirs, and who was ofen seen on the juries of musical competitions. From the late 1960s on, a ffh Farkas started to appear in the programmes of festivals of sacred music and of church concerts, eliciting interest with his slightly archaising and yet still new music. Te name was shared by one of the most sought-afer Hungarian composers active in the flm studios of Vienna and Copenhagen in the 1930s, the professor and director of the conservatory of Cluj-Napoca (in those days it was Kolozsvár in Hungary) in the early 1940s, also active as the chorus-master and, for a year, director of the local opera-house. -

The Hungarian Historical Review

Hungarian Historical Review 3, no. 4 (2014): 729–748 Zsófia Kádár The Difficulties of Conversion Non-Catholic Students in Jesuit Colleges in Western Hungary in the First Half of the Seventeenth Century The societies of the multiethnic and multilingual region of Central Europe became more diverse through the emergence of distinct confessions (Konfessionalisierung). The first half of the seventeenth century is especially interesting in this regard. In this period, the Catholic Church started to win back its positions in the Hungarian Kingdom as well, but the institutionalization of the Protestant denominations had by that time essentially reached completion. The schools, which were sustained by the various denominations, became the most efficient devices of religious education, persuasion and conversion. In this essay I present, through the example of the Jesuit colleges of western Hungary, the denominational proportions and movements of the students in the largely non-Catholic urban settings. Examining two basic types of sources, the annual accounts (Litterae Annuae) of the Society of Jesus and the registries of the Jesuit colleges in Győr and Pozsony (today Bratislava, Slovakia), I compare and contrast the data and venture an answer to questions regarding the kinds of opportunities non- Catholic students had in the Jesuit colleges. In contrast with the assertions made in earlier historiography, I conclude that conversion was not so widespread in the case of the non-Catholic students of the Jesuits. They were not discriminated against in their education, and some of them remained true to their confessions to the end of their studies in the colleges. Keywords: conversion, Jesuit colleges, school registries, annual accounts (Litterae Annuae), denominations in towns, urban history, Hungary, Győr, Pozsony, Pressburg, Bratislava, Sopron A student, the son of a soldier or a burgher, took leave of Calvinism, an act with which he completely infuriated his parents, so much so that his father planned to kill him. -

Gombos László FARKAS FERENC, a ZENE POLIHISZTORA*

364 Gombos László FARKAS FERENC, A ZENE POLIHISZTORA* A 19–20. században a közelmúlt jeles személyiségeit egyre gyakrabban ruházták fel az „utolsó polihisztor” címmel, ami az áttekinthetetlenné váló és specializáló- dó világban nosztalgikus múltba tekintéssel járt együtt. Bizonyos szempontból e kiválóságok közé sorolható Farkas Ferenc magyar zeneszerzô is, annak ellenére, hogy alkotóként csak a zenére koncentrált, és e területen hozott létre maradandót. Polihisztorvonásokat fedezhetünk fel sokoldalú érdeklôdésében és kivételes mû- veltségében, amellyel elbûvölte kortársait, és hazája egyik népszerû személyisége lett. Igazi életmûvészként „szakértônek” számított a nyelvek, a költészet, az iroda- lom és a konyhamûvészet terén, sôt fiatalon sikerrel próbálkozott a festészettel is. Kapcsolatteremtô képességéhez hozzájárult, hogy 10–12 nyelven beszélt többé- kevésbé folyékonyan. A zene és a zeneélet területén kivételes sokféleség jellemezte Farkas Ferencet; nem csupán mûfajait, stílusait, inspirációs forrásait és hangszer- összeállításait, ha- nem azokat a tevékenységeket is, amelyeket egyedülállóan hosszú, egy teljes év- századot átfogó pályája során végzett. Elsôsorban zeneszerzô volt, emellett tanár, korrepetitor, kórusvezetô, karmester, zenekari zongorista, iskolaigazgató és operai karigazgató, de közéleti szereplôként és zenei íróként is tevékeny volt. Az 1910- es évektôl szinte folyamatosan komponált, szó szerint élete utolsó pillanatáig, hiszen 2000 októberében egy Lorca- vers megzenésítése közben aludt el örökre. Tanári pályáját 1935- -

Magyar Zene ZENETUDOMÁNYI FOLYÓIRAT – 2015/4

ZENETUDOMÁNYI FOLYÓIRAT LIII. évfolyam, 4. szám . 2015. november Magyar Zene ZENETUDOMÁNYI FOLYÓIRAT – 2015/4 Szerkesztô / Editor: Péteri Judit A szám társszerkesztôje / Co- Editor of the present issue: Mikusi Balázs Szerkesztôbizottság / Editorial Board: Dalos Anna, Domokos Mária, Eckhardt Mária, Komlós Katalin, Mikusi Balázs, Péteri Lóránt, Székely András, Vikárius László Tanácsadó testület / Advisory Board: Malcolm Bilson (Ithaca, NY), Dorottya Fabian (Sydney), Farkas Zoltán, Jeney Zoltán, Kárpáti János, Laki Péter (Annandale- on- Hudson, NY), Rovátkay Lajos (Hannover), Sárosi Bálint, Somfai László, Szegedy- Maszák Mihály, Tallián Tibor A Magyar Zenetudományi és Zenekritikai Társaság lapja • Felelôs kiadó: a Társaság elnöke • Levelezési cím (belföldi elôfizetés): Magyar Zene, Magyar Zenetudományi és Zenekritikai Társaság, 1064 Budapest, Vörösmarty utca 35. ([email protected]) A folyóirat tartalomjegyzékét lásd: www.magyarzene.info, archívumát lásd: http:// mzzt.hu/index_HU.asp (Magyar Zene folyóirat menüpont) • Kéziratot nem ôrzünk meg, és csak felbélyegzett válaszborítékkal küldünk vissza • Külföldön elôfizetés- ben terjeszti a Batthyány Kultur- Press kft., telefon/telefax (+36 1) 201 88 91, (+36 1) 212 53 03; e- mail: batthyany@kultur- press.hu • Elôfizethetô a terjesztôktôl kért pos- tautalványon. Elôfizetési díj egy évre 2400 forint. Egyes szám ára 600 forint • Megje- lenik évente négyszer • Tördelés: graphoman • Címlapterv: Fodor Attila • Nyom- tatta az Argumentum Könyv- és Folyóiratkiadó kft. Budapesten • ISSN 0025- 0384 355 -

GUILTY NATION Or UNWILLING ALLY?

GUILTY NATION or UNWILLING ALLY? A short history of Hungary and the Danubian basin 1918-1939 By Joseph Varga Originally published in German as: Schuldige Nation oder VasalI wider Willen? Beitrage zur Zeitgeschichte Ungarns und des Donauraumes Teil 1918-1939 Published in Hungarian: Budapest, 1991 ISBN: 963 400 482 2 Veszprémi Nyomda Kft., Veszprém Translated into English and edited by: PETER CSERMELY © JOSEPH VARGA Prologue History is, first and foremost, a retelling of the past. It recounts events of former times, relates information about those events so that we may recognize the relationships between them. According to Aristoteles (Poetica, ch. IX), the historian differs from the poet only in that the former writes about events that have happened, while the latter of events that may yet happen. Modern history is mostly concerned with events of a political nature or those between countries, and on occasion with economic, social and cultural development. History must present the events in such a manner as to permit the still-living subjects to recognize them through their own memories, and permit the man of today to form an adequate picture of the events being recounted and their connections. Those persons who were mere objects in the events, or infrequently active participants, are barely able to depict objectively the events in which they participated. But is not the depiction of recent history subjective? Everyone recounts the events from their own perspective. A personal point of view does not, theoretically, exclude objectivity – only makes it relative. The measure of validity is the reliability of the narrator. The situation is entirely different with historical narratives that are written with a conscious intent to prove a point, or espouse certain interests. -

Hungary and the Hungarians

S.J. MAGYARÓDY Hungary and the Hungarians MATTHIAS CORVINUS PUBLISHERS Editor: Szabolcs J. Magyarody Principal translators: Péter Csermely, István Hegedűs Dr. Csaba Horváth, Judit Jókay Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 1-882785-23-1 Library of Congress Control Number: 2012947893 All expenses were contributed by North-American Hungarians No governments or government supported organizations contributed a single penny to the publication of this book and CD 2 CONTENTS FOREWORD ................................................................................................ 5 WHO ARE WE? ........................................................................................... 7 C. A. Macartney D. Litt. HUNGARY – A SHORT HISTORY * .................... 9 Fritz-Konrad Krüger HUNGARY AND WORLD WAR I. .......................... 18 László Gulyás A SHORT HISTORY OF THE TREATY OF TRIANON ..... 26 Yves De Daruvar THE TRAGIC FATE OF HUNGARY ............................ 33 John Flournoy Montgomery OPINION OF AN AMERICAN DIPLOMAT 38 J. F. Montgomery HUNGARIAN DECLARATION OF WAR ..................... 42 S.J. Magyaródy THE CENTRAL EUROPEAN SYNDROME .................... 47 RECOVERY OF LOST TERRITORIES ...................................................... 50 Dr. Edward Chászár THE FIRST VIENNA AWARD ................................. 52 RETAKING SUBCARPATHIA ................................................................... 54 THE SECOND VIENNA AWARD .............................................................. 56 TERRITORY CEDED BY ROUMANIA -

Musical Practices in the Balkans: Ethnomusicological Perspectives

MUSICAL PRACTICES IN THE BALKANS: ETHNOMUSICOLOGICAL PERSPECTIVES МУЗИЧКЕ ПРАКСЕ БАЛКАНА: ЕТНОМУЗИКОЛОШКЕ ПЕРСПЕКТИВЕ СРПСКА АКАДЕМИЈА НАУКА И УМЕТНОСТИ НАУЧНИ СКУПОВИ Књига CXLII ОДЕЉЕЊЕ ЛИКОВНЕ И МУЗИЧКЕ УМЕТНОСТИ Књига 8 МУЗИЧКЕ ПРАКСЕ БАЛКАНА: ЕТНОМУЗИКОЛОШКЕ ПЕРСПЕКТИВЕ ЗБОРНИК РАДОВА СА НАУЧНОГ СКУПА ОДРЖАНОГ ОД 23. ДО 25. НОВЕМБРА 2011. Примљено на X скупу Одељења ликовне и музичке уметности од 14. 12. 2012, на основу реферата академикâ Дејана Деспића и Александра Ломе У р е д н и ц и Академик ДЕЈАН ДЕСПИЋ др ЈЕЛЕНА ЈОВАНОВИЋ др ДАНКА ЛАЈИЋ-МИХАЈЛОВИЋ БЕОГРАД 2012 МУЗИКОЛОШКИ ИНСТИТУТ САНУ SERBIAN ACADEMY OF SCIENCES AND ARTS ACADEMIC CONFERENCES Volume CXLII DEPARTMENT OF FINE ARTS AND MUSIC Book 8 MUSICAL PRACTICES IN THE BALKANS: ETHNOMUSICOLOGICAL PERSPECTIVES PROCEEDINGS OF THE INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE HELD FROM NOVEMBER 23 TO 25, 2011 Accepted at the X meeting of the Department of Fine Arts and Music of 14.12.2012., on the basis of the review presented by Academicians Dejan Despić and Aleksandar Loma E d i t o r s Academician DEJAN DESPIĆ JELENA JOVANOVIĆ, PhD DANKA LAJIĆ-MIHAJLOVIĆ, PhD BELGRADE 2012 INSTITUTE OF MUSICOLOGY Издају Published by Српска академија наука и уметности Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts и and Музиколошки институт САНУ Institute of Musicology SASA Лектор за енглески језик Proof-reader for English Јелена Симоновић-Шиф Jelena Simonović-Schiff Припрема аудио прилога Audio examples prepared by Зоран Јерковић Zoran Jerković Припрема видео прилога Video examples prepared by Милош Рашић Милош Рашић Технички -

Prairie Winds T

e h prairie winds t TURBULENT Recorded at Foellinger Great Hall, WINDS Krannert Center for the Performing Arts, MUSIC FROM University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign EASTERN EUROPE on July 6 and 7, 2004 and June 4 and 6, 2005. Engineer: Jon Schoenoff WIND QUINTETS BY György Ligeti Producer: Stephen A. Taylor Ferenc Farkas Publishers: Farkas and Szervánszky (Editio Musica Budapest); Endre Szervánszky Ligeti (B. Schott’s Söhne, Mainz); Pavel Haas Haas (Boosey & Hawkes/Bote & Bock in cooperation with Tempo Praha) WWW.ALBANYRECORDS.COM TROY1193 ALBANY RECORDS U.S. 915 BROADWAY, ALBANY, NY 12207 TEL: 518.436.8814 FAX: 518.436.0643 ALBANY RECORDS U.K. BOX 137, KENDAL, CUMBRIA LA8 0XD TEL: 01539 824008 © 2010 ALBANY RECORDS MADE IN THE USA DDD WARNING: COPYRIGHT SUBSISTS IN ALL RECORDINGS ISSUED UNDER THIS LABEL. with a great corpus of works in his catalog, ranging in style from the traditionally melodic to the modernist— TURBULENT WINDS or imbued with the archaic elegance that characterizes his best-known piece, Early Hungarian Dances from MUSIC FROM EASTERN EUROPE the Seventeenth Century. This crystalline five-movement suite reportedly derived from a series of anonymous dance tunes dating from If music and civility are to flourish, Confucius reputedly said, we must first get names right. When it comes to the 1300s to the 1700s: a curtain-raising intrada, a slow dance, a lively shoulder dance, a stately chorea or the vast swath of land and rich diversity of peoples comprising Eastern Europe, however, names are often as circle dance, and a jump or saltarello. These he reworked and inventively scored for various instrumental bewilderingly unstable as quantum particles—or national boundaries. -

CHAMBER MUSIC for the E-FLAT CLARINET by Jacqueline Gail Eastwood Redshaw ---A Document Submitted to the Facult

Chamber Music for the E-Flat Clarinet Item Type text; Electronic Dissertation Authors Redshaw, Jacqueline Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 27/09/2021 01:51:40 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/194436 CHAMBER MUSIC FOR THE E-FLAT CLARINET by Jacqueline Gail Eastwood Redshaw ------------------- A Document Submitted to the Faculty of the SCHOOL OF MUSIC In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2 0 0 7 2 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As members of the Document Committee, we certify that we have read the document prepared by Jacqueline Gail Eastwood Redshaw entitled Chamber Music for the E-Flat Clarinet and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the document requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts _______________________________________________________________________ Date: October 16, 2007 Jerry Kirkbride _______________________________________________________________________ Date: October 16, 2007 William Dietz _______________________________________________________________________ Date: October 16, 2007 Gregg I. Hanson Final approval and acceptance of this document is contingent upon the candidate’s -

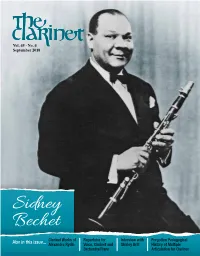

Sidney Bechet Clarinet Works of Repertoire for Interview with Forgotten Pedagogical Also in This Issue

Vol. 45 • No. 4 September 2018 Sidney Bechet Clarinet Works of Repertoire for Interview with Forgotten Pedagogical Also in this issue... Alexandre Rydin Voice, Clarinet and Shirley Brill History of Multiple Orchestra/Piano Articulation for Clarinet D’ADDARIO GIVES ME THE FREEDOM TO PRODUCE THE SOUND I HEAR IN MY HEAD. — JONATHAN GUNN REINVENTING CRAFTSMANSHIP FOR THE 21ST CENTURY. President’sThe EDITOR Rachel Yoder [email protected] ASSOCIATE EDITOR Dear Members and Jessica Harrie Friends of the International Clarinet Association: [email protected] s I write this message just days after the conclusion of EDITORIAL BOARD ClarinetFest® 2018, I continue to marvel at the fantastic Mitchell Estrin, Heike Fricke, Jessica Harrie, festival held on the beautiful Belgian coast of Ostend. We Caroline Hartig, Rachel Yoder are grateful to our friends Eddy Vanoosthuyse, artistic Adirector of ClarinetFest® 2018, and the Ostend team and family of MUSIC REVIEWS EDITOR the late Guido Six – Chantal Six Vandekerckhove, Bert Six and Gaby Gregory Barrett – [email protected] Six – who together organized a truly extraordinary and memorable festival featuring artists from over 55 countries. AUDIO REVIEWS EDITOR The first day alone contained an amazing array of concerts Chris Nichols – [email protected] including an homage to the legendary Guido Six by the Claribel Clarinet Choir, followed by the Honorary Member concert featuring Caroline Hartig GRAPHIC DESIGN Karl Leister, Luis Rossi, Antonio Saiote and the newest ICA honorary Karry Thomas Graphic Design member inductee, Charles Neidich. Later that evening was the [email protected] world premiere of the Piovani Clarinet Concerto with the Brussels Philharmonic, performed by Artistic Director Eddy Vanoosthuyse.