FERENC FARKAS Orchestral Music, Volume Three

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

President's Welcome

PRESIDENT’S WELCOME Friends, Colleagues, and Students, Welcome to the 82nd Annual Mississippi Bandmasters Association State Band Clinic in Natchez. The other members of the MBA Executive Board and I hope that you will experience growth, new perspectives, and renewed aspirations for teaching and learning music in your community during this year’s clinic. I would like to wish all of the students in attendance a heartfelt congratulations on participating in this esteemed event. You represent the very best of the students from your band programs – I encourage you to take that sentiment to heart. Thousands of students have shared in this honor for the last 82 years. Many of you will meet friends this weekend that you will have throughout your life. Lastly, I encourage you to take this opportunity to enjoy making music with others and learning from some of the most outstanding teachers in our country. For members of our association, take the time to visit with the exhibitors and clinicians throughout the weekend. Take advantage of the clinics and presentations that are offered so that you may leave Natchez with new insights and perspectives that you can use with your students at home. Clinic is also a time to renew old friendships and foster new ones. I hope that veteran teachers will take the time to get to know those that are new to our profession and new teachers will seek out the guidance of those with more experience. To our guest clinicians, exhibitors, featured ensembles, and conductors we welcome you and hope that you will enjoy your time with us. -

ED024693.Pdf

DO CUMEN T R UM? ED 024 693 24 TE 001 061 By-Bogard. Travis. Ed. International Conference on Theatre Education and Development: A Report on the Conference Sponsored by AETA (State Department. Washington. D.C.. June 14-18. 1967). Spons Agency- American Educational Theatre Association. Washington. D.C.;Office of Education (DHEW). Washington. D.C. Bureau of Research. Bureau No- BR- 7-0783 Pub Date Aug 68 Grant- OEG- 1- 7-070783-1713 Note- I28p. Available from- AETA Executive Office. John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts. 726 Jackson Place. N.V. Washington. D.C. (HC-$2.00). Journal Cit- Educational Theatre Journal; v20 n2A Aug 1968 Special Issue EDRS Price MF-$0.75 HC Not Available from EDRS. Descriptors-Acoustical Environment. Acting. Audiences. Auditoriums. Creative Dramatics. Drama. Dramatic Play. Dramatics. Education. Facilities. Fine Arts. Playwriting, Production Techniques. Speech. Speech Education. Theater Arts. Theaters The conference reported here was attended by educators and theater professionals from 24 countries, grouped into five discussion sections. Summaries of the proceedings of the discussion groups. each followed by postscripts by individual participants who wished to amplify portions of the summary. are presented. The discussion groups and the editors of their discussions are:"Training Theatre Personnel,Ralph Allen;"Theatre and Its Developing Audience," Francis Hodge; "Developing and Improving Artistic Leadership." Brooks McNamara; "Theatre in the Education Process." 0. G. Brockett; and "Improving Design for the Technical Function. Scenography. Structure and Function," Richard Schechner. A final section, "Soliloquies and Passages-at-Arms." containsselectedtranscriptions from audio tapes of portions of the conference. (JS) Educational Theatrejourna 1. -

La Suite Del Grande Arlecchino 1A

La Suite del Grande Arlecchino 1a. - Introduzione ca. Mario Totaro 2006/2007 1 Lastra media A Simone Brunetti Perc. I Lastra grave Perc. II 3 3 Grancassa Perc. III 5 Timpani 3 3 Perc. I [Lastra grave] Perc. II 3 [G.Cassa] Perc. III 3 3 Liberamente Flauto in Sol 10 3 3 3 3 Fl. 3 3 [Fl. in sol] 3 5 3 3 3 3 Fl. attacca: morendo 1b. - Primo quadro: La Nascita di Arlecchino (Processione, Caduta dell'Angelo e Apparizione del Demonio) SIPARIO 1 Bacchette da vibrafono dure 2 T. Blocks 2 Bongos Perc. II 2 Tom-toms 2 Congas A PRECEDUTO DA UN SACERDOTE, APPARE UN 7 3 3 3 Fl. in sol T.B. B. P. II T.T. C. CORTEO, RIVOLTO VERSO L'ALTO, FORMATO DA CREATURE MITOLOGICHE, SACRE E PROFANE (DIONISO, PERSEO ECC.) 14 3 3 3 3 3 3 Fl. in sol 3 3 3 T.B. B. P. II T.T. C. B 20 3 35 3 3 3 3 3 Fl. in sol 3 3 5 5 5 5 5 5 Cl. basso T.B. B. P. II T.T. C. 2b. - Secondo quadro: La Fame di Arlecchino (Pantomima) ARLECCHINO (ANCORA ZANNI CON COSTUME BIANCO) SCOPRE DI AVERE FAME CON URLA, PIANTI E CONVULSIONI Clar. Piccolo Mib flatterz. 1 6 Clarinetto 3 3 6 3 Corni in Fa con sord. Tromba in Do con sord. Trombone A lamentoso 6 6 Ob. 3 3 3 3 6 [Cl. Picc.] Cl. 3 33 6 6 Cl. basso Fg. 6 3 flatterz. 6 Tr. -

VIVACE AUTUMN / WINTER 2016 Photo © Martin Kubica Photo

VIVACEAUTUMN / WINTER 2016 Classical music review in Supraphon recordings Photo archive PPC archive Photo Photo © Jan Houda Photo LUKÁŠ VASILEK SIMONA ŠATUROVÁ TOMÁŠ NETOPIL Borggreve © Marco Photo Photo © David Konečný Photo Photo © Petr Kurečka © Petr Photo MARKO IVANOVIĆ RADEK BABORÁK RICHARD NOVÁK CP archive Photo Photo © Lukáš Kadeřábek Photo JANA SEMERÁDOVÁ • MAREK ŠTRYNCL • ROMAN VÁLEK Photo © Martin Kubica Photo XENIA LÖFFLER 1 VIVACE AUTUMN / WINTER 2016 Photo © Martin Kubica Photo Dear friends, of Kabeláč, the second greatest 20th-century Czech symphonist, only When looking over the fruits of Supraphon’s autumn harvest, I can eclipsed by Martinů. The project represents the first large repayment observe that a number of them have a common denominator, one per- to the man, whose upright posture and unyielding nature made him taining to the autumn of life, maturity and reflections on life-long “inconvenient” during World War II and the Communist regime work. I would thus like to highlight a few of our albums, viewed from alike, a human who remained faithful to his principles even when it this very angle of vision. resulted in his works not being allowed to be performed, paying the This year, we have paid special attention to Bohuslav Martinů in price of existential uncertainty and imperilment. particular. Tomáš Netopil deserves merit for an exquisite and highly A totally different hindsight is afforded by the unique album acclaimed recording (the Sunday Times Album of the Week, for of J. S. Bach’s complete Brandenburg Concertos, which has been instance), featuring one of the composer’s final two operas, Ariane, released on CD for the very first time. -

View List (.Pdf)

Symphony Society of New York Stadium Concert United States Premieres New York Philharmonic Commission as of November 30, 2020 NY PHIL Biennial Members of / musicians from the New York Philharmonic Click to jump to decade 1842-49 | 1850-59 | 1860-69 | 1870-79 | 1880-89 | 1890-99 | 1900-09 | 1910-19 | 1920-29 | 1930-39 1940-49 | 1950-59 | 1960-69 | 1970-79 | 1980-89 | 1990-99 | 2000-09 | 2010-19 | 2020 Composer Work Date Conductor 1842 – 1849 Beethoven Symphony No. 3, Sinfonia Eroica 18-Feb 1843 Hill Beethoven Symphony No. 7 18-Nov 1843 Hill Vieuxtemps Fantasia pour le Violon sur la quatrième corde 18-May 1844 Alpers Lindpaintner War Jubilee Overture 16-Nov 1844 Loder Mendelssohn The Hebrides Overture (Fingal's Cave) 16-Nov 1844 Loder Beethoven Symphony No. 8 16-Nov 1844 Loder Bennett Die Najaden (The Naiades) 1-Mar 1845 Wiegers Mendelssohn Symphony No. 3, Scottish 22-Nov 1845 Loder Mendelssohn Piano Concerto No. 1 17-Jan 1846 Hill Kalliwoda Symphony No. 1 7-Mar 1846 Boucher Furstenau Flute Concerto No. 5 7-Mar 1846 Boucher Donizetti "Tutto or Morte" from Faliero 20-May 1846 Hill Beethoven Symphony No. 9, Choral 20-May 1846 Loder Gade Grand Symphony 2-Dec 1848 Loder Mendelssohn Violin Concerto in E minor 24-Nov 1849 Eisfeld Beethoven Symphony No. 4 24-Nov 1849 Eisfeld 1850 – 1859 Schubert Symphony in C major, Great 11-Jan 1851 Eisfeld R. Schumann Introduction and Allegro appassionato for Piano and 25-Apr 1857 Eisfeld Orchestra Litolff Chant des belges 25-Apr 1857 Eisfeld R. Schumann Overture to the Incidental Music to Byron's Dramatic 21-Nov 1857 Eisfeld Poem, Manfred 1860 - 1869 Brahms Serenade No. -

BRITISH and COMMONWEALTH CONCERTOS from the NINETEENTH CENTURY to the PRESENT Sir Edward Elgar

BRITISH AND COMMONWEALTH CONCERTOS FROM THE NINETEENTH CENTURY TO THE PRESENT A Discography of CDs & LPs Prepared by Michael Herman Sir Edward Elgar (1857-1934) Born in Broadheath, Worcestershire, Elgar was the son of a music shop owner and received only private musical instruction. Despite this he is arguably England’s greatest composer some of whose orchestral music has traveled around the world more than any of his compatriots. In addition to the Conceros, his 3 Symphonies and Enigma Variations are his other orchestral masterpieces. His many other works for orchestra, including the Pomp and Circumstance Marches, Falstaff and Cockaigne Overture have been recorded numerous times. He was appointed Master of the King’s Musick in 1924. Piano Concerto (arranged by Robert Walker from sketches, drafts and recordings) (1913/2004) David Owen Norris (piano)/David Lloyd-Jones/BBC Concert Orchestra ( + Four Songs {orch. Haydn Wood}, Adieu, So Many True Princesses, Spanish Serenade, The Immortal Legions and Collins: Elegy in Memory of Edward Elgar) DUTTON EPOCH CDLX 7148 (2005) Violin Concerto in B minor, Op. 61 (1909-10) Salvatore Accardo (violin)/Richard Hickox/London Symphony Orchestra ( + Walton: Violin Concerto) BRILLIANT CLASSICS 9173 (2010) (original CD release: COLLINS CLASSICS COL 1338-2) (1992) Hugh Bean (violin)/Sir Charles Groves/Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra ( + Violin Sonata, Piano Quintet, String Quartet, Concert Allegro and Serenade) CLASSICS FOR PLEASURE CDCFP 585908-2 (2 CDs) (2004) (original LP release: HMV ASD2883) (1973) -

Juilliard String Quartet Areta Zhulla and Ronald Copes, Violins Roger Tapping, Viola Astrid Schween, Cello

Thursday Evening, December 12, 2019, at 7:30 The Juilliard School presents Juilliard String Quartet Areta Zhulla and Ronald Copes, Violins Roger Tapping, Viola Astrid Schween, Cello LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN (1770–1827) String Quartet No. 1 in F major, Op. 18, No. 1 Allegro con brio Adagio affettuoso ed appassionato Scherzo: Allegro molto Allegro GYÖRGY KURTÁG (b. 1926) 6 Moments musicaux, Op. 44 Invocatio (Un fragment) Footfalls (… as if someone were coming) Capriccio In memoriam Sebok˝ György Rappel des oiseaux ... (Étude pour les harmoniques) Les adieux (in Janáceks˘ Manier) Intermission BEETHOVEN Quartet No. 14 in C-sharp minor, Op. 131 Adagio ma non troppo e molto espressivo Allegro molto vivace Allegro moderato—Adagio Andante, ma non troppo e molto cantabile Presto Adagio quasi un poco andante Allegro Performance time: approximately 1 hour and 45 minutes, including an intermission The taking of photographs and the use of recording equipment are not permitted in this auditorium. Information regarding gifts to the school may be obtained from the Juilliard School Development Office, 60 Lincoln Center Plaza, New York, NY 10023-6588; (212) 799-5000, ext. 278 (juilliard.edu/giving). Alice Tully Hall Please make certain that all electronic devices are turned off during the performance. Notes on the Program published, in 1801. The D-major quartet (Op. 18, No. 3) was the first to be written; the By James M. Keller F-major (No. 1) and G-major (No. 2) followed, probably in that order; and the A major String Quartet No. 1 in F major, Op. 18, (No. 5), C minor (No. -

Uniting Commedia Dell'arte Traditions with the Spieltenor Repertoire

UNITING COMMEDIA DELL’ARTE TRADITIONS WITH THE SPIELTENOR REPERTOIRE Corey Trahan, B.M., M.M. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2012 APPROVED: Stephen Austin, Major Professor Paula Homer, Committee Member Lynn Eustis, Committee Member and Director of Graduate Studies in the College of Music James Scott, Dean of the School of Music James R. Meernik, Acting Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Trahan, Corey, Uniting Commedia dell’Arte Traditions with the Spieltenor repertoire. Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), May 2012, 85 pp., 6 tables, 35 illustrations, references, 84 titles. Sixteenth century commedia dell’arte actors relied on gaudy costumes, physical humor and improvisation to entertain audiences. The spieltenor in the modern operatic repertoire has a similar comedic role. Would today’s spieltenor benefit from consulting the commedia dell’arte’s traditions? To answer this question, I examine the commedia dell’arte’s history, stock characters and performance traditions of early troupes. The spieltenor is discussed in terms of vocal pedagogy and the fach system. I reference critical studies of the commedia dell’arte, sources on improvisatory acting, articles on theatrical masks and costuming, the commedia dell’arte as depicted by visual artists, commedia dell’arte techniques of movement, stances and postures. In addition, I cite vocal pedagogy articles, operatic repertoire and sources on the fach system. My findings suggest that a valid relationship exists between the commedia dell’arte stock characters and the spieltenor roles in the operatic repertoire. I present five case studies, pairing five stock characters with five spieltenor roles. -

TOCC 0230 Farkas Orch Music Vol. 4 Booklet Copy

FERENC FARKAS: WORKS FOR FLUTE AND CHAMBER ORCHESTRA by László Gombos Te surname Farkas (which means ‘wolf’) is not an uncommon one in Hungary. Tat is why a casual outsider might have thought that in the second half of the twentieth century there were several composers called Ferenc Farkas at work in Budapest at the same time. One of them was a successful composer of operas who was also represented by oratorios and orchestral and chamber music in a modern idiom, heard in the programmes of the major concert-halls. Another was a popular author of operettas, whose works, notching up hundreds of performances, were attended by a public entirely diferent from that of his namesake. A third composer conjured up the music of old times through various arrangements of early Hungarian dances and melodies and also found time to write incidental music to a number of flms, plays and radio plays. Hundreds of thousands of people knew a Ferenc Farkas who composed easy pieces for children, youth orchestras and amateur choirs, and who was ofen seen on the juries of musical competitions. From the late 1960s on, a ffh Farkas started to appear in the programmes of festivals of sacred music and of church concerts, eliciting interest with his slightly archaising and yet still new music. Te name was shared by one of the most sought-afer Hungarian composers active in the flm studios of Vienna and Copenhagen in the 1930s, the professor and director of the conservatory of Cluj-Napoca (in those days it was Kolozsvár in Hungary) in the early 1940s, also active as the chorus-master and, for a year, director of the local opera-house. -

Download Booklet

Classics Contemporaries of Mozart Collection COMPACT DISC ONE Franz Krommer (1759–1831) Symphony in D major, Op. 40* 28:03 1 I Adagio – Allegro vivace 9:27 2 II Adagio 7:23 3 III Allegretto 4:46 4 IV Allegro 6:22 Symphony in C minor, Op. 102* 29:26 5 I Largo – Allegro vivace 5:28 6 II Adagio 7:10 7 III Allegretto 7:03 8 IV Allegro 6:32 TT 57:38 COMPACT DISC TWO Carl Philipp Stamitz (1745–1801) Symphony in F major, Op. 24 No. 3 (F 5) 14:47 1 I Grave – Allegro assai 6:16 2 II Andante moderato – 4:05 3 III Allegretto/Allegro assai 4:23 Matthias Bamert 3 Symphony in G major, Op. 68 (B 156) 24:19 Symphony in C major, Op. 13/16 No. 5 (C 5) 16:33 5 I Allegro vivace assai 7:02 4 I Grave – Allegro assai 5:49 6 II Adagio 7:24 5 II Andante grazioso 6:07 7 III Menuetto e Trio 3:43 6 III Allegro 4:31 8 IV Rondo. Allegro 6:03 Symphony in G major, Op. 13/16 No. 4 (G 5) 13:35 Symphony in D minor (B 147) 22:45 7 I Presto 4:16 9 I Maestoso – Allegro con spirito quasi presto 8:21 8 II Andantino 5:15 10 II Adagio 4:40 9 III Prestissimo 3:58 11 III Menuetto e Trio. Allegretto 5:21 12 IV Rondo. Allegro 4:18 Symphony in D major ‘La Chasse’ (D 10) 16:19 TT 70:27 10 I Grave – Allegro 4:05 11 II Andante 6:04 12 III Allegro moderato – Presto 6:04 COMPACT DISC FOUR TT 61:35 Leopold Kozeluch (1747 –1818) 18:08 COMPACT DISC THREE Symphony in D major 1 I Adagio – Allegro 5:13 Ignace Joseph Pleyel (1757 – 1831) 2 II Poco adagio 5:07 3 III Menuetto e Trio. -

Concertino for Trumpet by Emil Petrovics (1930-2011): a Transcription for Brass Ensemble (2011) Directed by Dr

KEYSER, ALLYSON BLAIR, D.M.A. Concertino for Trumpet by Emil Petrovics (1930-2011): A Transcription for Brass Ensemble (2011) Directed by Dr. Edward Bach. 139 pp. Emil Petrovics (1930-2011) was an award-winning, prominent music figure in the history of Hungarian music. Known primarily for his one-act opera C’est la guerre, Petrovics also wrote film music, an oratorio, a string quartet, and numerous instrumental and vocal works. Among his instrumental music, Concertino is the only solo work Petrovics ever composed for solo trumpet with orchestra. Significant professional posts for Petrovics included professor of composition and conducting at the Franz Liszt Academy of Music, musical director of the Petöfi Theatre in Budapest, president of the Hungarian Association for Copyright Protection, and director of the Hungarian State Opera. In addition, Petrovics was a member of the Hungarian Parliament. The purpose of this study is to promote the work of Emil Petrovics through a performance edition of Concertino transcribed for brass ensemble. A secondary purpose of this study is to provide insight into the compositional process of Petrovics with the support of personal interviews with the composer prior to his death. The document presents a biographical sketch of Petrovics, a brief description of the three-movement work, and includes the arrangement of the Concertino for brass ensemble. Trumpeter Gyorgy Geiger and the Budapest Radio Symphony Orchestra commissioned the orchestral version of Concertino by Petrovics in 1990. Editio Musica Budapest published a piano reduction of Concertino, but the orchestral score was not published. Special permission to arrange the work was required and subsequently granted by the composer and EMB in December 2010. -

7619990104068.Pdf

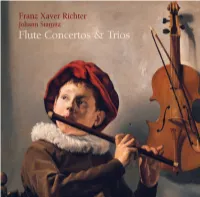

Franz Xaver Richter Johann Stamitz Flute Concertos & Trios Jana Semerádová transverse flute Ensemble Castor Petra Samhaber-Eckhardt, Recording: 14-16 February 2019, Landesmusikschule, Ried (Austria) Monika Toth violin Recording producer, digital editing & mastering: Uwe Walter Executive producer: Michael Sawall Peter Aigner viola Layout & booklet editor: Joachim Berenbold Translation: Katie Stephens (English) Peter Trefflinger violoncello Cover picture: “Boy playing the flute“, Judith Leyster (early 1630s), Nationalmuseum Stockholm Barbara Fischer violone + © 2019 note 1 music gmbh, Heidelberg, Germany CD manufactured in The Netherlands Erich Traxler harpsichord Franz Xaver Richter (1709-1789) Franz Xaver Richter Flute Concerto in E minor Harpsichord Trio in D major for transverse flute, strings & b.c. for obbligato harpsichord, violin & cello 1 Allegro moderato 9:09 10 Allegretto 7:18 2 Andantino 7:33 11 Larghetto 6:49 3 Allegro, ma non troppo 4:15 12 Presto, ma non troppo 3:00 Trio Sonata Op. 4 No. 1 in B flat major Harpsichord Trio in G minor for 2 violins & b.c. for obbligato harpsichord, violin & cello 4 Allegro brillante 3:25 13 Andante 7:37 5 Poco andante gracioso 5:23 14 Larghetto - Un poco andante 4:39 6 Allegro 2:39 15 Allegro, ma non troppo 3:02 Johann Stamitz (1717-1757) Flute Concerto in G major for transverse flute, strings & b.c. 7 Allegro moderato 6:07 8 Adagio 4:53 9 Presto 4:01 Was haben die Medici, die gleichsam wohlha- ein beträchtliches Vermögen verfügen konnte. erkannte Karl Theodor das repräsentative Einer der Vorreiter des neuen musikalischen bende und einflussreiche Bankiersfamilie aus Einer Überlieferung zufolge soll Anna Maria Potential der Instrumentalmusik.