Charles Koechlin's Silhouettes De Comã©Die for Bassoon and Orchestra: an in Depth Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Here I Played with Various Rhythm Sections in Festivals, Concerts, Clubs, Film Scores, on Record Dates and So on - the List Is Too Long

MICHAEL MANTLER RECORDINGS COMMUNICATION FONTANA 881 011 THE JAZZ COMPOSER'S ORCHESTRA Steve Lacy (soprano saxophone) Jimmy Lyons (alto saxophone) Robin Kenyatta (alto saxophone) Ken Mcintyre (alto saxophone) Bob Carducci (tenor saxophone) Fred Pirtle (baritone saxophone) Mike Mantler (trumpet) Ray Codrington (trumpet) Roswell Rudd (trombone) Paul Bley (piano) Steve Swallow (bass) Kent Carter (bass) Barry Altschul (drums) recorded live, April 10, 1965, New York TITLES Day (Communications No.4) / Communications No.5 (album also includes Roast by Carla Bley) FROM THE ALBUM LINER NOTES The Jazz Composer's Orchestra was formed in the fall of 1964 in New York City as one of the eight groups of the Jazz Composer's Guild. Mike Mantler and Carla Bley, being the only two non-leader members of the Guild, had decided to organize an orchestra made up of musicians both inside and outside the Guild. This group, then known as the Jazz Composer's Guild Orchestra and consisting of eleven musicians, began rehearsals in the downtown loft of painter Mike Snow for its premiere performance at the Guild's Judson Hall series of concerts in December 1964. The orchestra, set up in a large circle in the center of the hall, played "Communications no.3" by Mike Mantler and "Roast" by Carla Bley. The concert was so successful musically that the leaders decided to continue to write for the group and to give performances at the Guild's new headquarters, a triangular studio on top of the Village Vanguard, called the Contemporary Center. In early March 1965 at the first of these concerts, which were presented in a workshop style, the group had been enlarged to fifteen musicians and the pieces played were "Radio" by Carla Bley and "Communications no.4" (subtitled "Day") by Mike Mantler. -

La Suite Del Grande Arlecchino 1A

La Suite del Grande Arlecchino 1a. - Introduzione ca. Mario Totaro 2006/2007 1 Lastra media A Simone Brunetti Perc. I Lastra grave Perc. II 3 3 Grancassa Perc. III 5 Timpani 3 3 Perc. I [Lastra grave] Perc. II 3 [G.Cassa] Perc. III 3 3 Liberamente Flauto in Sol 10 3 3 3 3 Fl. 3 3 [Fl. in sol] 3 5 3 3 3 3 Fl. attacca: morendo 1b. - Primo quadro: La Nascita di Arlecchino (Processione, Caduta dell'Angelo e Apparizione del Demonio) SIPARIO 1 Bacchette da vibrafono dure 2 T. Blocks 2 Bongos Perc. II 2 Tom-toms 2 Congas A PRECEDUTO DA UN SACERDOTE, APPARE UN 7 3 3 3 Fl. in sol T.B. B. P. II T.T. C. CORTEO, RIVOLTO VERSO L'ALTO, FORMATO DA CREATURE MITOLOGICHE, SACRE E PROFANE (DIONISO, PERSEO ECC.) 14 3 3 3 3 3 3 Fl. in sol 3 3 3 T.B. B. P. II T.T. C. B 20 3 35 3 3 3 3 3 Fl. in sol 3 3 5 5 5 5 5 5 Cl. basso T.B. B. P. II T.T. C. 2b. - Secondo quadro: La Fame di Arlecchino (Pantomima) ARLECCHINO (ANCORA ZANNI CON COSTUME BIANCO) SCOPRE DI AVERE FAME CON URLA, PIANTI E CONVULSIONI Clar. Piccolo Mib flatterz. 1 6 Clarinetto 3 3 6 3 Corni in Fa con sord. Tromba in Do con sord. Trombone A lamentoso 6 6 Ob. 3 3 3 3 6 [Cl. Picc.] Cl. 3 33 6 6 Cl. basso Fg. 6 3 flatterz. 6 Tr. -

Jessica Charitos Senior Collaborative Piano Recital

THE BELHAVEN UNIVERSITY DEPARTMENT OF MUSIC Dr. Stephen W. Sachs, Chair presents Jessica Charitos Senior Collaborative Piano Recital Saturday, April 30, 2016 • 5:30 p.m. Belhaven University • Concert Hall This recital is presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Bachelor of Music degree in Performance: Collaborative Piano. There will be a reception after the program. Please come and greet the performers. Please refrain from the use of all flash and still photography during the concert. Please turn off all pagers and cell phones. PROGRAM The Worst Pies in London from Sweeny Todd Stephen Sondheim • b. 1930 No Good Deed from Wicked Stephen Schwartz • b. 1948 Madison Parrott, Soprano; Jessica Charitos, Accompanist Sonata in A major César Franck • 1822 - 1890 I. Allegretto ben moderato II. Allegro Hannah Wilson, Violin; Jessica Charitos, Accompanist INTERMISSION Polonaise in A major, Op. 40, No. 1 Frédéric Chopin • 1810 - 1849 Jessica Charitos, Piano Slavonic Dance Op. 46, No. 2 in E minor Antonín Dvorák • 1841 - 1904 Hungarian Dance, WoO.1, No.1 in G minor Johannes Brahms • 1833 - 1897 Hungarian Dance, WoO.1, No. 2 in D minor Hungarian Dance, WoO.1, No.5 in F# minor Jessica Charitos, Piano; Hannah van der Bijl, Piano Aubade Villageoise, Op.31, No.1 Arthur Foote • 1853 - 1937 Grace Chen, Flute; Jessica Charitos, Accompanist Over the Rainbow E. Y. Harburg & Harold Arlen • 1896 - 1981 Arranged by Ferrante & Teicher • 1905 - 1986 Jessica Charitos, Piano; Mali Lin, Piano PROGRAM NOTES In The Worst Pie in London, Sweeny Todd walks captured by the Wizard’s guard. He was into the meat pie shop on Fleet Street. -

College Orchestra Director Programming Decisions Regarding Classical Twentieth-Century Music Mark D

James Madison University JMU Scholarly Commons Dissertations The Graduate School Summer 2017 College orchestra director programming decisions regarding classical twentieth-century music Mark D. Taylor James Madison University Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/diss201019 Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Taylor, Mark D., "College orchestra director programming decisions regarding classical twentieth-century music" (2017). Dissertations. 132. https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/diss201019/132 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the The Graduate School at JMU Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of JMU Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. College Orchestra Director Programming Decisions Regarding Classical Twentieth-Century Music Mark David Taylor A Doctor of Musical Arts Document submitted to the Graduate Faculty of JAMES MADISON UNIVERSITY In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts School of Music August 2017 FACULTY COMMITTEE Committee Chair: Dr. Eric Guinivan Committee Members/ Readers: Dr. Mary Jean Speare Mr. Foster Beyers Acknowledgments Dr. Robert McCashin, former Director of Orchestras and Professor of Orchestral Conducting at James Madison University (JMU) as well as a co-founder of College Orchestra Directors Association (CODA), served as an important sounding-board as the study emerged. Dr. McCashin was particularly helpful in pointing out the challenges of undertaking such a study. I would have been delighted to have Dr. McCashin serve as the chair of my doctoral committee, but he retired from JMU before my study was completed. -

Scaramouche and the Commedia Dell'arte

Scaramouche Sibelius’s horror story Eija Kurki © Finnish National Opera and Ballet archives / Tenhovaara Scaramouche. Ballet in 3 scenes; libr. Paul [!] Knudsen; mus. Sibelius; ch. Emilie Walbom. Prod. 12 May 1922, Royal Dan. B., CopenhaGen. The b. tells of a demonic fiddler who seduces an aristocratic lady; afterwards she sees no alternative to killinG him, but she is so haunted by his melody that she dances herself to death. Sibelius composed this, his only b. score, in 1913. Later versions by Lemanis in Riga (1936), R. HiGhtower for de Cuevas B. (1951), and Irja Koskkinen [!] in Helsinki (1955). This is the description of Sibelius’s Scaramouche, Op. 71, in The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Ballet. Initially, however, Sibelius’s Scaramouche was not a ballet but a pantomime. It was completed in 1913, to a Danish text of the same name by Poul Knudsen, with the subtitle ‘Tragic Pantomime’. The title of the work refers to Italian theatre, to the commedia dell’arte Scaramuccia character. Although the title of the work is Scaramouche, its main character is the female dancing role Blondelaine. After Scaramouche was completed, it was then more or less forgotten until it was published five years later, whereupon plans for a performance were constantly being made until it was eventually premièred in 1922. Performances of Scaramouche have 1 attracted little attention, and also Sibelius’s music has remained unknown. It did not become more widely known until the 1990s, when the first full-length recording of this remarkable composition – lasting more than an hour – appeared. Previous research There is very little previous research on Sibelius’s Scaramouche. -

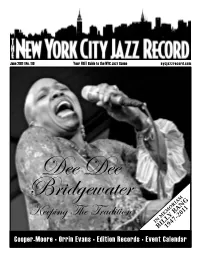

Keeping the Tradition Y B 2 7- in MEMO4 BILL19 Cooper-Moore • Orrin Evans • Edition Records • Event Calendar

June 2011 | No. 110 Your FREE Guide to the NYC Jazz Scene nycjazzrecord.com Dee Dee Bridgewater RIAM ANG1 01 Keeping The Tradition Y B 2 7- IN MEMO4 BILL19 Cooper-Moore • Orrin Evans • Edition Records • Event Calendar It’s always a fascinating process choosing coverage each month. We’d like to think that in a highly partisan modern world, we actually live up to the credo: “We New York@Night Report, You Decide”. No segment of jazz or improvised music or avant garde or 4 whatever you call it is overlooked, since only as a full quilt can we keep out the cold of commercialism. Interview: Cooper-Moore Sometimes it is more difficult, especially during the bleak winter months, to 6 by Kurt Gottschalk put together a good mixture of feature subjects but we quickly forget about that when June rolls around. It’s an embarrassment of riches, really, this first month of Artist Feature: Orrin Evans summer. Just like everyone pulls out shorts and skirts and sandals and flipflops, 7 by Terrell Holmes the city unleashes concert after concert, festival after festival. This month we have the Vision Fest; a mini-iteration of the Festival of New Trumpet Music (FONT); the On The Cover: Dee Dee Bridgewater inaugural Blue Note Jazz Festival taking place at the titular club as well as other 9 by Marcia Hillman city venues; the always-overwhelming Undead Jazz Festival, this year expanded to four days, two boroughs and ten venues and the 4th annual Red Hook Jazz Encore: Lest We Forget: Festival in sight of the Statue of Liberty. -

View List (.Pdf)

Symphony Society of New York Stadium Concert United States Premieres New York Philharmonic Commission as of November 30, 2020 NY PHIL Biennial Members of / musicians from the New York Philharmonic Click to jump to decade 1842-49 | 1850-59 | 1860-69 | 1870-79 | 1880-89 | 1890-99 | 1900-09 | 1910-19 | 1920-29 | 1930-39 1940-49 | 1950-59 | 1960-69 | 1970-79 | 1980-89 | 1990-99 | 2000-09 | 2010-19 | 2020 Composer Work Date Conductor 1842 – 1849 Beethoven Symphony No. 3, Sinfonia Eroica 18-Feb 1843 Hill Beethoven Symphony No. 7 18-Nov 1843 Hill Vieuxtemps Fantasia pour le Violon sur la quatrième corde 18-May 1844 Alpers Lindpaintner War Jubilee Overture 16-Nov 1844 Loder Mendelssohn The Hebrides Overture (Fingal's Cave) 16-Nov 1844 Loder Beethoven Symphony No. 8 16-Nov 1844 Loder Bennett Die Najaden (The Naiades) 1-Mar 1845 Wiegers Mendelssohn Symphony No. 3, Scottish 22-Nov 1845 Loder Mendelssohn Piano Concerto No. 1 17-Jan 1846 Hill Kalliwoda Symphony No. 1 7-Mar 1846 Boucher Furstenau Flute Concerto No. 5 7-Mar 1846 Boucher Donizetti "Tutto or Morte" from Faliero 20-May 1846 Hill Beethoven Symphony No. 9, Choral 20-May 1846 Loder Gade Grand Symphony 2-Dec 1848 Loder Mendelssohn Violin Concerto in E minor 24-Nov 1849 Eisfeld Beethoven Symphony No. 4 24-Nov 1849 Eisfeld 1850 – 1859 Schubert Symphony in C major, Great 11-Jan 1851 Eisfeld R. Schumann Introduction and Allegro appassionato for Piano and 25-Apr 1857 Eisfeld Orchestra Litolff Chant des belges 25-Apr 1857 Eisfeld R. Schumann Overture to the Incidental Music to Byron's Dramatic 21-Nov 1857 Eisfeld Poem, Manfred 1860 - 1869 Brahms Serenade No. -

BRITISH and COMMONWEALTH CONCERTOS from the NINETEENTH CENTURY to the PRESENT Sir Edward Elgar

BRITISH AND COMMONWEALTH CONCERTOS FROM THE NINETEENTH CENTURY TO THE PRESENT A Discography of CDs & LPs Prepared by Michael Herman Sir Edward Elgar (1857-1934) Born in Broadheath, Worcestershire, Elgar was the son of a music shop owner and received only private musical instruction. Despite this he is arguably England’s greatest composer some of whose orchestral music has traveled around the world more than any of his compatriots. In addition to the Conceros, his 3 Symphonies and Enigma Variations are his other orchestral masterpieces. His many other works for orchestra, including the Pomp and Circumstance Marches, Falstaff and Cockaigne Overture have been recorded numerous times. He was appointed Master of the King’s Musick in 1924. Piano Concerto (arranged by Robert Walker from sketches, drafts and recordings) (1913/2004) David Owen Norris (piano)/David Lloyd-Jones/BBC Concert Orchestra ( + Four Songs {orch. Haydn Wood}, Adieu, So Many True Princesses, Spanish Serenade, The Immortal Legions and Collins: Elegy in Memory of Edward Elgar) DUTTON EPOCH CDLX 7148 (2005) Violin Concerto in B minor, Op. 61 (1909-10) Salvatore Accardo (violin)/Richard Hickox/London Symphony Orchestra ( + Walton: Violin Concerto) BRILLIANT CLASSICS 9173 (2010) (original CD release: COLLINS CLASSICS COL 1338-2) (1992) Hugh Bean (violin)/Sir Charles Groves/Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra ( + Violin Sonata, Piano Quintet, String Quartet, Concert Allegro and Serenade) CLASSICS FOR PLEASURE CDCFP 585908-2 (2 CDs) (2004) (original LP release: HMV ASD2883) (1973) -

Black North American and Caribbean Music in European Metropolises a Transnational Perspective of Paris and London Music Scenes (1920S-1950S)

Black North American and Caribbean Music in European Metropolises A Transnational Perspective of Paris and London Music Scenes (1920s-1950s) Veronica Chincoli Thesis submitted for assessment with a view to obtaining the degree of Doctor of History and Civilization of the European University Institute Florence, 15 April 2019 European University Institute Department of History and Civilization Black North American and Caribbean Music in European Metropolises A Transnational Perspective of Paris and London Music Scenes (1920s- 1950s) Veronica Chincoli Thesis submitted for assessment with a view to obtaining the degree of Doctor of History and Civilization of the European University Institute Examining Board Professor Stéphane Van Damme, European University Institute Professor Laura Downs, European University Institute Professor Catherine Tackley, University of Liverpool Professor Pap Ndiaye, SciencesPo © Veronica Chincoli, 2019 No part of this thesis may be copied, reproduced or transmitted without prior permission of the author Researcher declaration to accompany the submission of written work Department of History and Civilization - Doctoral Programme I Veronica Chincoli certify that I am the author of the work “Black North American and Caribbean Music in European Metropolises: A Transnatioanl Perspective of Paris and London Music Scenes (1920s-1950s). I have presented for examination for the Ph.D. at the European University Institute. I also certify that this is solely my own original work, other than where I have clearly indicated, in this declaration and in the thesis, that it is the work of others. I warrant that I have obtained all the permissions required for using any material from other copyrighted publications. I certify that this work complies with the Code of Ethics in Academic Research issued by the European University Institute (IUE 332/2/10 (CA 297). -

CLAUDE DEBUSSY in 2018: a CENTENARY CELEBRATION PROGRAMME Monday 19 - Friday 23 March 2018 CLAUDE DEBUSSY in 2018: a CENTENARY CELEBRATION

19-23/03/18 CLAUDE DEBUSSY IN 2018: A CENTENARY CELEBRATION PROGRAMME Monday 19 - Friday 23 March 2018 CLAUDE DEBUSSY IN 2018: A CENTENARY CELEBRATION Patron Her Majesty The Queen President Sir John Tomlinson CBE Principal Professor Linda Merrick Chairman Nick Prettejohn To enhance everyone’s experience of this event please try to stifle coughs and sneezes, avoid unwrapping sweets during the performance and switch off mobile phones, pagers and digital alarms. Please do not take photographs or video in 0161 907 5555 X the venue. Latecomers will not be admitted until a suitable break in the 1 2 3 4 5 6 programme, or at the first interval, whichever is the more appropriate. 7 8 9 * 0 # < @ > The RNCM reserves the right to change artists and/or programmes as necessary. The RNCM reserves the right of admission. 0161 907 5555 X 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 * 0 # < @ > Welcome It gives me great pleasure to welcome you to Claude Debussy in 2018: a Centenary Celebration, marking the 100th anniversary of the death of Claude Debussy on 25 March 1918. Divided into two conferences, ‘Debussy Perspectives’ at the RNCM and ‘Debussy’s Late work and the Musical Worlds of Wartime Paris’ at the University of Glasgow, this significant five-day event brings together world experts and emerging scholars to reflect critically on the current state of Debussy research of all kinds. With guest speakers from 13 countries, including Brazil, China and the USA, we explore Debussy’s editions and sketches, critical and interpretative approaches, textual and cultural-historical analysis, and his legacy in performance, recording, composition and arrangement. -

Uniting Commedia Dell'arte Traditions with the Spieltenor Repertoire

UNITING COMMEDIA DELL’ARTE TRADITIONS WITH THE SPIELTENOR REPERTOIRE Corey Trahan, B.M., M.M. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2012 APPROVED: Stephen Austin, Major Professor Paula Homer, Committee Member Lynn Eustis, Committee Member and Director of Graduate Studies in the College of Music James Scott, Dean of the School of Music James R. Meernik, Acting Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Trahan, Corey, Uniting Commedia dell’Arte Traditions with the Spieltenor repertoire. Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), May 2012, 85 pp., 6 tables, 35 illustrations, references, 84 titles. Sixteenth century commedia dell’arte actors relied on gaudy costumes, physical humor and improvisation to entertain audiences. The spieltenor in the modern operatic repertoire has a similar comedic role. Would today’s spieltenor benefit from consulting the commedia dell’arte’s traditions? To answer this question, I examine the commedia dell’arte’s history, stock characters and performance traditions of early troupes. The spieltenor is discussed in terms of vocal pedagogy and the fach system. I reference critical studies of the commedia dell’arte, sources on improvisatory acting, articles on theatrical masks and costuming, the commedia dell’arte as depicted by visual artists, commedia dell’arte techniques of movement, stances and postures. In addition, I cite vocal pedagogy articles, operatic repertoire and sources on the fach system. My findings suggest that a valid relationship exists between the commedia dell’arte stock characters and the spieltenor roles in the operatic repertoire. I present five case studies, pairing five stock characters with five spieltenor roles. -

Ferruccio Busoni – the Six Sonatinas: an Artist’S Journey 1909-1920 – His Language and His World

Ferruccio Busoni – The Six Sonatinas: An Artist’s Journey 1909-1920 – his language and his world Jeni Slotchiver This is the concluding second Part of the author’s in-depth appreciation of these greatly significant piano works. Part I was published in our issue No 1504 July- September 2015. t summer’s end, 1914, Busoni asks for artists in exile from Europe. Audiences are A a year’s leave of absence from his in thin supply. He writes to Edith Andreae, position as director of the Liceo Musicale June 1915, “I didn’t dare set to work on in Bologna. He signs a contract for his the opera… for fear that a false start American tour and remains in Berlin over would destroy my last moral foothold.” Christmas, playing a Bach concert to Busoni begins an orchestral comp- benefit charities. This is the first all-Bach osition as a warm-up for Arlecchino, the piano recital for the Berlin public, and Rondò Arlecchinesco. He sets down ideas, Dent writes that it is received with hoping they might be a useful study, if all “discourteous ingratitude.” Busoni outlines else fails, and writes, “If the humour in the his plan for Dr. Faust, recording in his Rondò manifests itself at all, it will have a diary, “Everything came together like a heartrending effect.” With bold harmonic vision.” By Christmastime, the text is language, Busoni clearly defines this complete. With the outbreak of war in composition as his last experimental work. 1914 and an uncertain future, Busoni sails The years give way to compassionate to New York with his family on 5 January, reflection.