"Riverside Wren Pairs Jointly Defend Their Territories Against Simulated Intruders"

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Best of Costa Rica March 19–31, 2019

THE BEST OF COSTA RICA MARCH 19–31, 2019 Buffy-crowned Wood-Partridge © David Ascanio LEADERS: DAVID ASCANIO & MAURICIO CHINCHILLA LIST COMPILED BY: DAVID ASCANIO VICTOR EMANUEL NATURE TOURS, INC. 2525 WALLINGWOOD DRIVE, SUITE 1003 AUSTIN, TEXAS 78746 WWW.VENTBIRD.COM THE BEST OF COSTA RICA March 19–31, 2019 By David Ascanio Photo album: https://www.flickr.com/photos/davidascanio/albums/72157706650233041 It’s about 02:00 AM in San José, and we are listening to the widespread and ubiquitous Clay-colored Robin singing outside our hotel windows. Yet, it was still too early to experience the real explosion of bird song, which usually happens after dawn. Then, after 05:30 AM, the chorus started when a vocal Great Kiskadee broke the morning silence, followed by the scratchy notes of two Hoffmann´s Woodpeckers, a nesting pair of Inca Doves, the ascending and monotonous song of the Yellow-bellied Elaenia, and the cacophony of an (apparently!) engaged pair of Rufous-naped Wrens. This was indeed a warm welcome to magical Costa Rica! To complement the first morning of birding, two boreal migrants, Baltimore Orioles and a Tennessee Warbler, joined the bird feast just outside the hotel area. Broad-billed Motmot . Photo: D. Ascanio © Victor Emanuel Nature Tours 2 The Best of Costa Rica, 2019 After breakfast, we drove towards the volcanic ring of Costa Rica. Circling the slope of Poas volcano, we eventually reached the inspiring Bosque de Paz. With its hummingbird feeders and trails transecting a beautiful moss-covered forest, this lodge offered us the opportunity to see one of Costa Rica´s most difficult-to-see Grallaridae, the Scaled Antpitta. -

Costa Rica: the Introtour | July 2017

Tropical Birding Trip Report Costa Rica: The Introtour | July 2017 A Tropical Birding SET DEPARTURE tour Costa Rica: The Introtour July 15 – 25, 2017 Tour Leader: Scott Olmstead INTRODUCTION This year’s July departure of the Costa Rica Introtour had great luck with many of the most spectacular, emblematic birds of Central America like Resplendent Quetzal (photo right), Three-wattled Bellbird, Great Green and Scarlet Macaws, and Keel-billed Toucan, as well as some excellent rarities like Black Hawk- Eagle, Ochraceous Pewee and Azure-hooded Jay. We enjoyed great weather for birding, with almost no morning rain throughout the trip, and just a few delightful afternoon and evening showers. Comfortable accommodations, iconic landscapes, abundant, delicious meals, and our charismatic driver Luís enhanced our time in the field. Our group, made up of a mix of first- timers to the tropics and more seasoned tropical birders, got along wonderfully, with some spying their first-ever toucans, motmots, puffbirds, etc. on this trip, and others ticking off regional endemics and hard-to-get species. We were fortunate to have several high-quality mammal sightings, including three monkey species, Derby’s Wooly Opossum, Northern Tamandua, and Tayra. Then there were many www.tropicalbirding.com +1-409-515-9110 [email protected] Page Tropical Birding Trip Report Costa Rica: The Introtour | July 2017 superb reptiles and amphibians, among them Emerald Basilisk, Helmeted Iguana, Green-and- black and Strawberry Poison Frogs, and Red-eyed Leaf Frog. And on a daily basis we saw many other fantastic and odd tropical treasures like glorious Blue Morpho butterflies, enormous tree ferns, and giant stick insects! TOP FIVE BIRDS OF THE TOUR (as voted by the group) 1. -

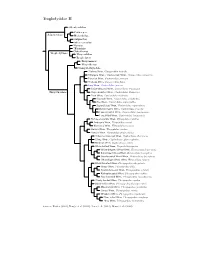

Troglodytidae Species Tree

Troglodytidae I Rock Wren, Salpinctes obsoletus Canyon Wren, Catherpes mexicanus Sumichrast’s Wren, Hylorchilus sumichrasti Nava’s Wren, Hylorchilus navai Salpinctinae Nightingale Wren / Northern Nightingale-Wren, Microcerculus philomela Scaly-breasted Wren / Southern Nightingale-Wren, Microcerculus marginatus Flutist Wren, Microcerculus ustulatus Wing-banded Wren, Microcerculus bambla ?Gray-mantled Wren, Odontorchilus branickii Odontorchilinae Tooth-billed Wren, Odontorchilus cinereus Bewick’s Wren, Thryomanes bewickii Carolina Wren, Thryothorus ludovicianus Thrush-like Wren, Campylorhynchus turdinus Stripe-backed Wren, Campylorhynchus nuchalis Band-backed Wren, Campylorhynchus zonatus Gray-barred Wren, Campylorhynchus megalopterus White-headed Wren, Campylorhynchus albobrunneus Fasciated Wren, Campylorhynchus fasciatus Cactus Wren, Campylorhynchus brunneicapillus Yucatan Wren, Campylorhynchus yucatanicus Giant Wren, Campylorhynchus chiapensis Bicolored Wren, Campylorhynchus griseus Boucard’s Wren, Campylorhynchus jocosus Spotted Wren, Campylorhynchus gularis Rufous-backed Wren, Campylorhynchus capistratus Sclater’s Wren, Campylorhynchus humilis Rufous-naped Wren, Campylorhynchus rufinucha Pacific Wren, Nannus pacificus Winter Wren, Nannus hiemalis Eurasian Wren, Nannus troglodytes Zapata Wren, Ferminia cerverai Marsh Wren, Cistothorus palustris Sedge Wren, Cistothorus platensis ?Merida Wren, Cistothorus meridae ?Apolinar’s Wren, Cistothorus apolinari Timberline Wren, Thryorchilus browni Tepui Wren, Troglodytes rufulus Troglo dytinae Ochraceous -

Printable PDF Format

Field Guides Tour Report Safari Brazil: The Pantanal & More 2019 Sep 21, 2019 to Oct 6, 2019 Marcelo Padua & Dan Lane For our tour description, itinerary, past triplists, dates, fees, and more, please VISIT OUR TOUR PAGE. We experienced the amazing termitaria-covered landscape of Emas National Park, where participant Rick Thompson got this evocative image, including two Aplomado Falcons, and a Pampas Deer. Brazil is a big place, and it is home to a wide variety of biomes. Among its most famous are the Amazon and the Pantanal, both occupy huge areas and have their respective hydrologies to thank for their existence. In addition to these are drier regions that cut the humid Amazon from the humid Atlantic Forest, this is known as the “Dry Diagonal,” home to the grasslands we observed at Emas, the chapada de Cipo, and farther afield, the Chaco, Pampas, and Caatinga. We were able to dip our toes into several of these incredible features, beginning with the Pantanal, one of the world’s great wetlands, and home to a wide array of animals, fish, birds, and other organisms. In addition to daytime outings to enjoy the birdlife and see several of the habitats of the region (seasonally flooded grasslands, gallery forest, deciduous woodlands, and open country that does not flood), we were able to see a wide array of mammals during several nocturnal outings, culminating in such wonderful results as seeing multiple big cats (up to three Ocelots and a Jaguar on one night!), foxes, skunks, raccoons, Giant Anteaters, and others. To have such luck as this in the Americas is something special! Our bird list from the region included such memorable events as seeing an active Jabiru nest, arriving at our lodging at Aguape to a crowd of Hyacinth Macaws, as well as enjoying watching the antics of their cousins the Blue-and-yellow Macaws. -

2020 Costa Rica Tour Species List

Costa Rica Guides: Ernesto Carman Eagle-Eye Tours February 22 - March 09, 2020 and Paz Angulo Irola Bird Species - Costa Rica Seen/ Common Name Scientific Name Heard TINAMOUS 1 Great Tinamou Tinamus major 1 2 Little Tinamou Crypturellus soui H DUCKS, GEESE, AND WATERFOWL 3 Black-bellied Whistling-Duck Dendrocygna autumnalis 1 4 Muscovy Duck Cairina moschata 1 5 Blue-winged Teal Anas discors 1 GUANS, CHACHALACAS, AND CURASSOWS 6 Gray-headed Chachalaca Ortalis cinereiceps 1 7 Crested Guan Penelope purpurascens 1 8 Black Guan Chamaepetes unicolor 1 9 Great Curassow Crax rubra 1 NEW WORLD QUAIL 10 Crested Bobwhite Colinus cristatus H 11 Buffy-crowned Wood-Partridge Dendrortyx leucophrys H 12 Spotted Wood-Quail Odontophorus guttatus 1 STORKS 13 Jabiru Jabiru mycteria 1 14 Wood Stork Mycteria americana 1 FRIGATEBIRDS 15 Magnificent Frigatebird Fregata magnificens 1 CORMORANTS AND SHAGS 16 Neotropic Cormorant Phalacrocorax brasilianus 1 ANHINGAS 17 Anhinga Anhinga anhinga 1 PELICANS 18 Brown Pelican Pelecanus occidentalis 1 HERONS, EGRETS, AND BITTERNS 19 Fasciated Tiger-Heron Tigrisoma fasciatum 1 20 Bare-throated Tiger-Heron Tigrisoma mexicanum 1 21 Pinnated Bittern Botaurus pinnatus 1 22 Great Blue Heron Ardea herodias 1 23 Great Egret Ardea alba 1 24 Snowy Egret Egretta thula 1 25 Little Blue Heron Egretta caerulea 1 26 Tricolored Heron Egretta tricolor 1 27 Cattle Egret Bubulcus ibis 1 28 Green Heron Butorides virescens 1 29 Boat-billed Heron Cochlearius cochlearius 1 30 Yellow-crowned Night-Heron Nyctanassa violacea 1 IBISES AND SPOONBILLS -

Panama's Canopy Tower and El Valle's Canopy Lodge

FIELD REPORT – Panama’s Canopy Tower and El Valle’s Canopy Lodge January 4-16, 2019 Orange-bellied Trogon © Ruthie Stearns Blue Cotinga © Dave Taliaferro Geoffroy’s Tamarin © Don Pendleton Ocellated Antbird © Carlos Bethancourt White-tipped Sicklebill © Jeri Langham Prepared by Jeri M. Langham VICTOR EMANUEL NATURE TOURS, INC. 2525 WALLINGWOOD DR., AUSTIN, TX 78746 Phone: 512-328-5221 or 800-328-8368 / Fax: 512-328-2919 [email protected] / www.ventbird.com Myriads of magazine articles have touted Panama’s incredible Canopy Tower, a former U.S. military radar tower transformed by Raúl Arias de Para when the U.S. relinquished control of the Panama Canal Zone. It sits atop 900-foot Semaphore Hill overlooking Soberania National Park. While its rooms are rather spartan, the food is Panama’s Canopy Tower © Ruthie Stearns excellent and the opportunity to view birds at dawn from the 360º rooftop Observation Deck above the treetops is outstanding. Twenty minutes away is the start of the famous Pipeline Road, possibly one of the best birding roads in Central and South America. From our base, daily birding outings are made to various locations in Central Panama, which vary from the primary forest around the tower, to huge mudflats near Panama City and, finally, to cool Cerro Azul and Cerro Jefe forest. An enticing example of what awaits visitors to this marvelous birding paradise can be found in excerpts taken from the Journal I write during every tour and later e- mail to participants. These are taken from my 17-page, January 2019 Journal. On our first day at Canopy Tower, with 5 of the 8 participants having arrived, we were touring the Observation Deck on top of Canopy Tower when Ruthie looked up and called my attention to a bird flying in our direction...it was a Black Hawk-Eagle! I called down to others on the floor below and we watched it disappear into the distant clouds. -

Assessing Bird Migrations Verônica Fernandes Gama

Assessing Bird Migrations Verônica Fernandes Gama Master of Philosophy, Remote Sensing Bachelor of Biological Sciences (Honours) A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at The University of Queensland in 2019 School of Biological Sciences Abstract Birds perform many types of migratory movements that vary remarkably both geographically and between taxa. Nevertheless, nomenclature and definitions of avian migrations are often not used consistently in the published literature, and the amount of information available varies widely between taxa. Although comprehensive global lists of migrants exist, these data oversimplify the breadth of types of avian movements, as species are classified into just a few broad classes of movements. A key knowledge gap exists in the literature concerning irregular, small-magnitude migrations, such as irruptive and nomadic, which have been little-studied compared with regular, long-distance, to-and- fro migrations. The inconsistency in the literature, oversimplification of migration categories in lists of migrants, and underestimation of the scope of avian migration types may hamper the use of available information on avian migrations in conservation decisions, extinction risk assessments and scientific research. In order to make sound conservation decisions, understanding species migratory movements is key, because migrants demand coordinated management strategies where protection must be achieved over a network of sites. In extinction risk assessments, the threatened status of migrants and non-migrants is assessed differently in the International Union for Conservation of Nature Red List, and the threatened status of migrants could be underestimated if information regarding their movements is inadequate. In scientific research, statistical techniques used to summarise relationships between species traits and other variables are data sensitive, and thus require accurate and precise data on species migratory movements to produce more reliable results. -

ON 22(3) 421-436.Pdf

ORNITOLOGIA NEOTROPICAL 22: 421–436, 2011 © The Neotropical Ornithological Society COMMUNITY COMPOSITION AND ANNUAL SURVIVAL OF LOWLAND TROPICAL FOREST BIRDS ON THE OSA PENINSULA, COSTA RICA Scott Wilson1,2,3, Douglas M. Collister2, & Amy G. Wilson1,2 1Smithsonian Migratory Bird Center, National Zoological Park, Washington, DC, 20008, USA. 2Calgary Bird Banding Society, 3426 Lane Crescent, Calgary, AB, T3E 5X2, Canada. 3Present address: Canadian Wildlife Service, Environment Canada, 115 Perimeter Road, Saskatoon, SK, S7N 0X4, Canada. E-mail: [email protected] Resumen. – Composición de la comunidad y la supervivencia anual de las aves de los bosques tropicales de tierras bajas en la Peninsula de Osa, Costa Rica. – La deforestación tropical ha dado lugar a muchos paisajes donde los bosques existen en forma de parches de diferente tamaño pero a la vez, estos están conectados dentro de un paisaje dominado por humanos. Entender las implicaciones de estos paisajes para la dinámica de la biodiversidad y la población es hoy en día un gran reto para la biología de la conservación tropical. Hemos examinado la composición de la comunidad y la superviven- cia anual de las aves en un paisaje parcialmente deforestadas en la Península de Osa de Costa Rica, que es una región de alta biodiversidad y de creciente preocupación para su conservación. Nuestro estudio se basó en un estudio de siete años de redes de niebla en un terreno de 3 ha y un año entero de conteo de puntos. Estos recuentos se llevaron a cabo en dos tipos de hábitat: un paisaje fragmentado, con una mezcla de parches de bosque y áreas de agricultura abierta, y un parche de 100 ha de bosque maduro. -

Libro Del Curso Biología De Campo 2010

Universidad de Costa Rica Escuela de Biología Libro del Curso Biología de Campo 2010 Universidad de Costa Rica Facultad de Ciencias Escuela de Biología Biología de Campo 2010 Coordinadores: Federico Bolaños Eduardo Chacón Jorge Lobo Golfito, Puntarenas Enero-Febrero 2010 2 Indice Presentación del curso .........................................................................................................6 Lista de participantes:...........................................................................................................7 Fotografía de grupo ..............................................................................................................8 Fotografías de participantes ................................................................................................9 Trabajos Grupales ..............................................................................................................23 Éxito reproductivo de la palma neotropical dioica Chamaedorea tepejilote (Arecales: Arecaceae) .........................................................................................................................24 Efecto de la invasión del bastón del emperador Etlingera elatior (Jack) R. M. Smith (Zingiberaceae) en la diversidad y abundancia de plántulas en un bosque secundario ..30 Éxito reproductivo y enantiostilia en Senna reticulata (Caesalpinaceae) ...........................37 Sistema de polinización por viento en Myriocarpa longipes (Urticaceae) ..........................46 Curvas de polen para Myriocarpa longipes -

Troglodytidae Tree, Part 2

Troglodytidae II Odontorchilus Catherpes Salpinctinae Hylorchilus Salpinctes Microcerculus Nannus ?Ferminia Cistothorus Troglo dytinae Thryorchilus Troglo dytes Thryomanes Thryothorus Campylorhynchus ?Rufous Wren, Cinnycerthia unirufa ?Sharpe’s Wren / Sepia-brown Wren, Cinnycerthia olivascens Peruvian Wren, Cinnycerthia peruana ?Fulvous Wren, Cinnycerthia fulva Gray Wren, Cantorchilus griseus Stripe-throated Wren, Cantorchilus leucopogon Thryothorinae Stripe-breasted Wren, Cantorchilus thoracicus Plain Wren, Cantorchilus modestus Riverside Wren, Cantorchilus semibadius Bay Wren, Cantorchilus nigricapillus Superciliated Wren, Cantorchilus superciliaris Buff-breasted Wren, Cantorchilus leucotis Fawn-breasted Wren, Cantorchilus guarayanus Long-billed Wren, Cantorchilus longirostris Rufous-and-white Wren, Thryophilus rufalbus Antioquia Wren, Thryophilus sernai Niceforo’s Wren, Thryophilus nicefori Sinaloa Wren, Thryophilus sinaloa Banded Wren, Thryophilus pleurostictus ?Chestnut-breasted Wren, Cyphorhinus thoracicus ?Song Wren, Cyphorhinus phaeocephalus Musician Wren, Cyphorhinus arada White-bellied Wren, Uropsila leucogastra White-breasted Wood-Wren, Henicorhina leucosticta Bar-winged Wood-Wren, Henicorhina leucoptera Gray-breasted Wood-Wren, Henicorhina leucophrys ?Munchique Wood-Wren, Henicorhina negreti Black-throated Wren, Pheugopedius atrogularis Happy Wren, Pheugopedius felix Speckle-breasted Wren, Pheugopedius sclateri Rufous-breasted Wren, Pheugopedius rutilus Spot-breasted Wren, Pheugopedius maculipectus ?Sooty-headed Wren, Pheugopedius spadix Black-bellied Wren, Pheugopedius fasciatoventris Moustached Wren, Pheugopedius genibarbis Coraya Wren, Pheugopedius coraya Whiskered Wren, Pheugopedius mystacalis Plain-tailed Wren, Pheugopedius euophrys ?Inca Wren, Pheugopedius eisenmanni Sources: Barker (2004), Dingle et al. (2006), Lara et al. (2012), Mann et al. (2006).. -

AOU Check-List Supplement

AOU Check-list Supplement The Auk 117(3):847–858, 2000 FORTY-SECOND SUPPLEMENT TO THE AMERICAN ORNITHOLOGISTS’ UNION CHECK-LIST OF NORTH AMERICAN BIRDS This first Supplement since publication of the 7th Icterus prosthemelas, Lonchura cantans, and L. atricap- edition (1998) of the AOU Check-list of North American illa); (3) four species are changed (Caracara cheriway, Birds summarizes changes made by the Committee Glaucidium costaricanum, Myrmotherula pacifica, Pica on Classification and Nomenclature between its re- hudsonia) and one added (Caracara lutosa) by splits constitution in late 1998 and 31 January 2000. Be- from now-extralimital forms; (4) four scientific cause the makeup of the Committee has changed sig- names of species are changed because of generic re- nificantly since publication of the 7th edition, it allocation (Ibycter americanus, Stercorarius skua, S. seems appropriate to outline the way in which the maccormicki, Molothrus oryzivorus); (5) one specific current Committee operates. The philosophy of the name is changed for nomenclatural reasons (Baeolo- Committee is to retain the present taxonomic or dis- phus ridgwayi); (6) the spelling of five species names tributional status unless substantial and convincing is changed to make them gramatically correct rela- evidence is published that a change should be made. tive to the generic name (Jacamerops aureus, Poecile The Committee maintains an extensive agenda of atricapilla, P. hudsonica, P. cincta, Buarremon brunnein- potential action items, including possible taxonomic ucha); (7) one English name is changed to conform to changes and changes to the list of species included worldwide use (Long-tailed Duck), one is changed in the main text or the Appendix. -

Download Trip Report

COSTA RICA ESCAPE: SET DEPARTURE TRIP REPORT 3 – 11 JANUARY 2019 By Eduardo Ormaeche Resplendent Quetzal (photo Tracy Marr) www.birdingecotours.com [email protected] 2 | TRIP REPORT Costa Rica Escape January 2019 Overview This Costa Rica Escape 2019 trip was our first tour of the year, starting only three days after the arrival of the New Year. It was an incredible trip, which allowed us to see the best of the country in just a week. Costa Rica is perhaps the easiest country to bird in the tropical Americas, and most of the Neotropical families are well represented. With great roads and tourist and service facilities infrastructure the country, and this trip in particular, is the best choice for those who come to the tropics for the first time. Our adventure started in San José, the capital of Costa Rica, and we managed to explore different habitats and ecosystems, ranging from the Caribbean foothills to the cloudforest mountains of Savegre in central Costa Rica to end at the Pacific slope at Carara National Park and the Río Tárcoles. Of the 934 species of birds that occur in Costa Rica we managed to record more than a third in a week only! We recorded 320 species as well as an additional three species that were heard only. Our trip list included sightings of amazing species such as Resplendent Quetzal, Boat-billed Heron, American Pygmy Kingfisher, Violet Sabrewing, Black Guan, Spotted Wood Quail, Streak-chested Antpitta, Silvery-fronted Tapaculo, Great Potoo, Spectacled and Crested Owls, Flame-throated Warbler, Long-tailed Silky-flycatcher, Fiery-billed Aracari, Spot- fronted Swift, Prong-billed Barbet, American Dipper, White-crested Coquette, Black- crested Coquette, Black-and-yellow Tanager, Spangle-cheeked Tanager, and White-eared Ground Sparrow.