Fondo De Biodiversidad Sostenible

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Costa Rica 2020

Sunrise Birding LLC COSTA RICA TRIP REPORT January 30 – February 5, 2020 Photos: Talamanca Hummingbird, Sunbittern, Resplendent Quetzal, Congenial Group! Sunrise Birding LLC COSTA RICA TRIP REPORT January 30 – February 5, 2020 Leaders: Frank Mantlik & Vernon Campos Report and photos by Frank Mantlik Highlights and top sightings of the trip as voted by participants Resplendent Quetzals, multi 20 species of hummingbirds Spectacled Owl 2 CR & 32 Regional Endemics Bare-shanked Screech Owl 4 species Owls seen in 70 Black-and-white Owl minutes Suzy the “owling” dog Russet-naped Wood-Rail Keel-billed Toucan Great Potoo Tayra!!! Long-tailed Silky-Flycatcher Black-faced Solitaire (& song) Rufous-browed Peppershrike Amazing flora, fauna, & trails American Pygmy Kingfisher Sunbittern Orange-billed Sparrow Wayne’s insect show-and-tell Volcano Hummingbird Spangle-cheeked Tanager Purple-crowned Fairy, bathing Rancho Naturalista Turquoise-browed Motmot Golden-hooded Tanager White-nosed Coati Vernon as guide and driver January 29 - Arrival San Jose All participants arrived a day early, staying at Hotel Bougainvillea. Those who arrived in daylight had time to explore the phenomenal gardens, despite a rain storm. Day 1 - January 30 Optional day-trip to Carara National Park Guides Vernon and Frank offered an optional day trip to Carara National Park before the tour officially began and all tour participants took advantage of this special opportunity. As such, we are including the sightings from this day trip in the overall tour report. We departed the Hotel at 05:40 for the drive to the National Park. En route we stopped along the road to view a beautiful Turquoise-browed Motmot. -

Costa Rica Photo Journey: July 2017

Tropical Birding Trip Report Costa Rica Photo Journey: July 2017 Costa Rica Photo Journey 16-25 July 2017 Tour Leader: Jay Packer Many thanks to Deepak Ramineedi for allowing us to include his photos in this trip report. This Yellow-throated Toucan at Laguna del Lagarto wasn’t bothered at all by the rain. Note: Except where noted otherwise, all photos in this trip report were taken by Jay Packer. www.tropicalbirding.com +1- 409-515-9110 [email protected] Page 1 Tropical Birding Trip Report Costa Rica Photo Journey: July 2017 Introduction This Costa Rican photo journey featured visits to five regions of this small Central American country. We covered the moist Caribbean slope, Caribbean lowlands, dry forests on the Pacific slope, a large tropical river, and cloud forests of the volcanic highlands. The clients on the tour were a young couple and their 8-month old son. Given the considerations of traveling with an infant, the pace of the tour was relaxed and much of the photography was done at feeders or from the car. Even so, the diversity of Costa Rica was impressive as we encountered almost 200 species, photographing most of the targets that we hoped to see. Photographic highlights of the trip included stunning shots of toucan species in the rain, great hummingbird multiflash photography, a nesting pair of Turquoise-browed Motmots, Spectacled Owl, King Vultures, Resplendent Quetzal, very cooperative Great Green and Scarlet Macaws, Costa Rican Pygmy-Owl, and more. 16 July 2017 We began the tour with a drive out of San Jose to the well known Casa de Cope, west of Guápiles. -

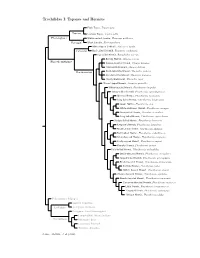

Topazes and Hermits

Trochilidae I: Topazes and Hermits Fiery Topaz, Topaza pyra Topazini Crimson Topaz, Topaza pella Florisuginae White-necked Jacobin, Florisuga mellivora Florisugini Black Jacobin, Florisuga fusca White-tipped Sicklebill, Eutoxeres aquila Eutoxerini Buff-tailed Sicklebill, Eutoxeres condamini Saw-billed Hermit, Ramphodon naevius Bronzy Hermit, Glaucis aeneus Phaethornithinae Rufous-breasted Hermit, Glaucis hirsutus ?Hook-billed Hermit, Glaucis dohrnii Threnetes ruckeri Phaethornithini Band-tailed Barbthroat, Pale-tailed Barbthroat, Threnetes leucurus ?Sooty Barbthroat, Threnetes niger ?Broad-tipped Hermit, Anopetia gounellei White-bearded Hermit, Phaethornis hispidus Tawny-bellied Hermit, Phaethornis syrmatophorus Mexican Hermit, Phaethornis mexicanus Long-billed Hermit, Phaethornis longirostris Green Hermit, Phaethornis guy White-whiskered Hermit, Phaethornis yaruqui Great-billed Hermit, Phaethornis malaris Long-tailed Hermit, Phaethornis superciliosus Straight-billed Hermit, Phaethornis bourcieri Koepcke’s Hermit, Phaethornis koepckeae Needle-billed Hermit, Phaethornis philippii Buff-bellied Hermit, Phaethornis subochraceus Scale-throated Hermit, Phaethornis eurynome Sooty-capped Hermit, Phaethornis augusti Planalto Hermit, Phaethornis pretrei Pale-bellied Hermit, Phaethornis anthophilus Stripe-throated Hermit, Phaethornis striigularis Gray-chinned Hermit, Phaethornis griseogularis Black-throated Hermit, Phaethornis atrimentalis Reddish Hermit, Phaethornis ruber ?White-browed Hermit, Phaethornis stuarti ?Dusky-throated Hermit, Phaethornis squalidus Streak-throated Hermit, Phaethornis rupurumii Cinnamon-throated Hermit, Phaethornis nattereri Little Hermit, Phaethornis longuemareus ?Tapajos Hermit, Phaethornis aethopygus ?Minute Hermit, Phaethornis idaliae Polytminae: Mangos Lesbiini: Coquettes Lesbiinae Coeligenini: Brilliants Patagonini: Giant Hummingbird Lampornithini: Mountain-Gems Tro chilinae Mellisugini: Bees Cynanthini: Emeralds Trochilini: Amazilias Source: McGuire et al. (2014).. -

Bird List Column A: 1 = 70-90% Chance Column B: 2 = 30-70% Chance Column C: 3 = 10-30% Chance

Colombia: Chocó Prospective Bird List Column A: 1 = 70-90% chance Column B: 2 = 30-70% chance Column C: 3 = 10-30% chance A B C Tawny-breasted Tinamou 2 Nothocercus julius Highland Tinamou 3 Nothocercus bonapartei Great Tinamou 2 Tinamus major Berlepsch's Tinamou 3 Crypturellus berlepschi Little Tinamou 1 Crypturellus soui Choco Tinamou 3 Crypturellus kerriae Horned Screamer 2 Anhima cornuta Black-bellied Whistling-Duck 1 Dendrocygna autumnalis Fulvous Whistling-Duck 1 Dendrocygna bicolor Comb Duck 3 Sarkidiornis melanotos Muscovy Duck 3 Cairina moschata Torrent Duck 3 Merganetta armata Blue-winged Teal 3 Spatula discors Cinnamon Teal 2 Spatula cyanoptera Masked Duck 3 Nomonyx dominicus Gray-headed Chachalaca 1 Ortalis cinereiceps Colombian Chachalaca 1 Ortalis columbiana Baudo Guan 2 Penelope ortoni Crested Guan 3 Penelope purpurascens Cauca Guan 2 Penelope perspicax Wattled Guan 2 Aburria aburri Sickle-winged Guan 1 Chamaepetes goudotii Great Curassow 3 Crax rubra Tawny-faced Quail 3 Rhynchortyx cinctus Crested Bobwhite 2 Colinus cristatus Rufous-fronted Wood-Quail 2 Odontophorus erythrops Chestnut Wood-Quail 1 Odontophorus hyperythrus Least Grebe 2 Tachybaptus dominicus Pied-billed Grebe 1 Podilymbus podiceps Magnificent Frigatebird 1 Fregata magnificens Brown Booby 2 Sula leucogaster ________________________________________________________________________________________________________ WINGS ● 1643 N. Alvernon Way Ste. 109 ● Tucson ● AZ ● 85712 ● www.wingsbirds.com (866) 547 9868 Toll free US + Canada ● Tel (520) 320-9868 ● Fax (520) -

SPLITS, LUMPS and SHUFFLES Splits, Lumps and Shuffles Alexander C

>> SPLITS, LUMPS AND SHUFFLES Splits, lumps and shuffles Alexander C. Lees This series focuses on recent taxonomic proposals—be they entirely new species, splits, lumps or reorganisations—that are likely to be of greatest interest to birders. This latest instalment includes a new Scytalopus tapaculo and a new subspecies of Three-striped Warbler, reviews of species limits in Grey-necked Wood Rails and Pearly Parakeets and comprehensive molecular studies of Buff-throated Woodcreepers, Sierra Finches, Red-crowned Ant Tanagers and Siskins. Get your lists out! Splits proposed for Grey- Pearly Parakeet is two species necked Wood Rails The three subspecies of Pearly Parakeet Pyrrhura lepida form a species complex with Crimson- The Grey-necked Wood Rail Aramides cajaneus bellied Parakeet P. perlata and replace each other is both the most widespread (occurring from geographically across a broad swathe of southern Mexico to Argentina) and the only polytypic Amazonia east of the Madeira river all the way member of its genus. Although all populations to the Atlantic Ocean. Understanding the nature are ‘diagnosable’ in having an entirely grey neck of this taxonomic variation is an important task, and contrasting chestnut chest, there is much as collectively their range sits astride much of variation in the colours of the nape, lower chest the Amazonian ‘Arc of Deforestation’ and the and mantle, differences amongst which have led to broadly-defined Brazilian endemic Pearly Parakeet the recognition of nine subspecies. Marcondes and is already considered to be globally Vulnerable. Silveira (2015) recently explored the taxonomy of Somenzari and Silveira (2015) recently investigated Grey-necked Wood Rails based on morphological the taxonomy of the three lepida subspecies (the and vocal characteristics using a sample of 800 nominate P. -

Rapid Ecological Assessment Mayflower Bocawina National Park

Rapid Ecological Assessment Mayflower Bocawina National Park Volume II - Appendix J.C. Meerman B. Holland, A. Howe, H. L. Jones, B. W. Miller This report was prepared for: Friends of Mayflower under a grant provided by PACT. July 31, 2003 J. C. Meerman – REA – Mayflower Bocawina National Park – Appendices – July 2003 – page 1 Appendix 1 Birdlist of Mayflower Bocawina National Park (MBNP) Status: R = Resident, W =Winter visitor, D = Drys season resident, A = Accidental visitor, T = Transient. MBNP: X = Recorded during REA, ? = Species in need of confirmation, MN = Reported by Mamanoots Resort, some may need confirmation English Name Scientific name Local name(s) Status MBNP TINAMOUS - TINAMIDAE Great Tinamou Tinamus major Blue-footed partridge R X Little Tinamou Crypturellus soui Bawley R X Slaty-breasted Tinamou Crypturellus boucardi Red-footed partridge R ? HERONS - ARDEIDAE Bare-throated Tiger Heron Tigrisoma mexicanum Barking gaulin R X Great Egret Egretta alba Gaulin, Garza blanca WR MN Little Blue Heron Egretta caerulea Blue Gaulin, Garza morene W X Cattle Egret Bubulcus ibis Gaulin, Garza blanca WR X AMERICAN VULTURES - CATHARTIDAE Black Vulture Coragyps atratus John Crow, Sope WR X Turkey Vulture Cathartes aura Doctor John Crow, Sope WR X King Vulture Sarcoramphus papa King John Crow, Sope real R X KITES, HAWKS, EAGLES AND ALLIES - ACCIPITRIDAE Swallow-tailed Kite Elanoides forficatus Scissors-tailed hawk DT X Plumbeous Kite Ictinia plumbea D MN White Hawk Leucopternis albicollis R X Gray Hawk Asturina nitidus R X Great Black-Hawk -

(Bird) Species List

Aves (Bird) Species List Higher Classification1 Kingdom: Animalia, Phylum: Chordata, Class: Reptilia, Diapsida, Archosauria, Aves Order (O:) and Scientific Name2 Family (F:) English Name2 Spanish Name3 Costa Rican Common Names3 (E = endemic to Costa Rica) O: Tinamiformes F: Tinamidae Highland Tinamou Tinamú Serrano Gallina de monte de Altura, Nothocercus bonapartei Gongolona Great Tinamou Tinamú Grande Gallina de monte, Perdiz, Tinamus major Gongolona, Yerre O: Galliformes F: Cracidae Black Guan Pava Negra Pajuila Chamaepetes unicolor (E) Gray-headed Chachalaca Chachalaca Cabecigrís Chachalaca, Pavita Ortalis cinereiceps F: Odontophoridae Buffy-crowned Wood-Partridge Perdiz Montañera Chirrascuá Dendrortyx leucophrys Spotted Wood-Quail Codorniz Moteada Odontophorus guttatus Black-breasted Wood-Quail Codorniz Pechinegra Gallinita de Monte, Chirrascuá, Odontophorus leucolaemus (E) Huevos de Chancho O: Suliformes F: Fregatidae Magnificent Frigatebird Rabihorcado Magno Tijereta, Fragata, Zopilote de Mar Fregata magnificens O: Pelecaniformes F: Ardeidae Cattle Egret Garcilla Bueyera Garcilla Ganadera, Garza Vaquera, Bubulcus ibis Garza de Ganado Fasciated Tiger-Heron7 Garza-Tigre de Río Martín Peña, Pájaro Vaco Tigrisoma fasciatum O: Charadriiformes F: Scolopacidae Spotted Sandpiper Andarríos Maculado Alzacolita, Piririza, Tigüiza Actitis macularius O: Gruiformes F: Rallidae Gray-Cowled Wood-Rail Rascón Cuelligrís Chirincoco, Pomponé, Pone-pone Aramides cajaneus O: Accipitriformes F: Cathartidae Turkey Vulture Zopilote Cabecirrojo Zonchite, -

Checklistccamp2016.Pdf

2 3 Participant’s Name: Tour Company: Date#1: / / Tour locations Date #2: / / Tour locations Date #3: / / Tour locations Date #4: / / Tour locations Date #5: / / Tour locations Date #6: / / Tour locations Date #7: / / Tour locations Date #8: / / Tour locations Codes used in Column A Codes Sample Species a = Abundant Red-lored Parrot c = Common White-headed Wren u = Uncommon Gray-cheeked Nunlet r = Rare Sapayoa vr = Very rare Wing-banded Antbird m = Migrant Bay-breasted Warbler x = Accidental Dwarf Cuckoo (E) = Endemic Stripe-cheeked Woodpecker Species marked with an asterisk (*) can be found in the birding areas visited on the tour outside of the immediate Canopy Camp property such as Nusagandi, San Francisco Reserve, El Real and Darien National Park/Cerro Pirre. Of course, 4with incredible biodiversity and changing environments, there is always the possibility to see species not listed here. If you have a sighting not on this list, please let us know! No. Bird Species 1A 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Tinamous Great Tinamou u 1 Tinamus major Little Tinamou c 2 Crypturellus soui Ducks Black-bellied Whistling-Duck 3 Dendrocygna autumnalis u Muscovy Duck 4 Cairina moschata r Blue-winged Teal 5 Anas discors m Curassows, Guans & Chachalacas Gray-headed Chachalaca 6 Ortalis cinereiceps c Crested Guan 7 Penelope purpurascens u Great Curassow 8 Crax rubra r New World Quails Tawny-faced Quail 9 Rhynchortyx cinctus r* Marbled Wood-Quail 10 Odontophorus gujanensis r* Black-eared Wood-Quail 11 Odontophorus melanotis u Grebes Least Grebe 12 Tachybaptus dominicus u www.canopytower.com 3 BirdChecklist No. -

The Birds of Hacienda Palo Verde, Guanacaste, Costa Rica

The Birds of Hacienda Palo Verde, Guanacaste, Costa Rica PAUL SLUD SMITHSONIAN CONTRIBUTIONS TO ZOOLOGY • NUMBER 292 SERIES PUBLICATIONS OF THE SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION Emphasis upon publication as a means of "diffusing knowledge" was expressed by the first Secretary of the Smithsonian. In his formal plan for the Institution, Joseph Henry outlined a program that included the following statement: "It is proposed to publish a series of reports, giving an account of the new discoveries in science, and of the changes made from year to year in all branches of knowledge." This theme of basic research has been adhered to through the years by thousands of titles issued in series publications under the Smithsonian imprint, commencing with Smithsonian Contributions to Knowledge in 1848 and continuing with the following active series: Smithsonian Contributions to Anthropology Smithsonian Contributions to Astrophysics Smithsonian Contributions to Botany Smithsonian Contributions to the Earth Sciences Smithsonian Contributions to Paleobiology Smithsonian Contributions to Zoo/ogy Smithsonian Studies in Air and Space Smithsonian Studies in History and Technology In these series, the Institution publishes small papers and full-scale monographs that report the research and collections of its various museums and bureaux or of professional colleagues in the world cf science and scholarship. The publications are distributed by mailing lists to libraries, universities, and similar institutions throughout the world. Papers or monographs submitted for series publication are received by the Smithsonian Institution Press, subject to its own review for format and style, only through departments of the various Smithsonian museums or bureaux, where the manuscripts are given substantive review. Press requirements for manuscript and art preparation are outlined on the inside back cover. -

Tinamiformes – Falconiformes

LIST OF THE 2,008 BIRD SPECIES (WITH SCIENTIFIC AND ENGLISH NAMES) KNOWN FROM THE A.O.U. CHECK-LIST AREA. Notes: "(A)" = accidental/casualin A.O.U. area; "(H)" -- recordedin A.O.U. area only from Hawaii; "(I)" = introducedinto A.O.U. area; "(N)" = has not bred in A.O.U. area but occursregularly as nonbreedingvisitor; "?" precedingname = extinct. TINAMIFORMES TINAMIDAE Tinamus major Great Tinamou. Nothocercusbonapartei Highland Tinamou. Crypturellus soui Little Tinamou. Crypturelluscinnamomeus Thicket Tinamou. Crypturellusboucardi Slaty-breastedTinamou. Crypturellus kerriae Choco Tinamou. GAVIIFORMES GAVIIDAE Gavia stellata Red-throated Loon. Gavia arctica Arctic Loon. Gavia pacifica Pacific Loon. Gavia immer Common Loon. Gavia adamsii Yellow-billed Loon. PODICIPEDIFORMES PODICIPEDIDAE Tachybaptusdominicus Least Grebe. Podilymbuspodiceps Pied-billed Grebe. ?Podilymbusgigas Atitlan Grebe. Podicepsauritus Horned Grebe. Podicepsgrisegena Red-neckedGrebe. Podicepsnigricollis Eared Grebe. Aechmophorusoccidentalis Western Grebe. Aechmophorusclarkii Clark's Grebe. PROCELLARIIFORMES DIOMEDEIDAE Thalassarchechlororhynchos Yellow-nosed Albatross. (A) Thalassarchecauta Shy Albatross.(A) Thalassarchemelanophris Black-browed Albatross. (A) Phoebetriapalpebrata Light-mantled Albatross. (A) Diomedea exulans WanderingAlbatross. (A) Phoebastriaimmutabilis Laysan Albatross. Phoebastrianigripes Black-lootedAlbatross. Phoebastriaalbatrus Short-tailedAlbatross. (N) PROCELLARIIDAE Fulmarus glacialis Northern Fulmar. Pterodroma neglecta KermadecPetrel. (A) Pterodroma -

COSTA RICA: the Introtour (Group 1) Feb 2017

Tropical Birding Trip Report COSTA RICA: The Introtour (Group 1) Feb 2017 A Tropical Birding set departure tour COSTA RICA: The Introtour 13th - 23rd February 2017 (Group 1) Tour Leader: Sam Woods (Report and all photos by Sam Woods) This Keel-billed Toucan lit up our first afternoon, near Braulio Carrillo National Park. The same day also featured Thicket Antpitta and THREE species of owl during the daytime… Ferruginous Pygmy, Crested and Spectacled Owls. 1 www.tropicalbirding.com +1-409-515-9110 [email protected] Page Tropical Birding Trip Report COSTA RICA: The Introtour (Group 1) Feb 2017 INTRODUCTION There can be few countries in the World as welcoming to birders as Costa Rica; everywhere we went birds were plentiful and frequently people with binoculars were in attendance too. Indeed, Costa Rica makes you feel odd if you are NOT wearing a pair. We enjoyed a fantastic tour of some of the most revered sites in Costa Rican birding; we started out near San Jose in the dry Central Valley, before driving over to the Caribbean side, where foothill birding was done in and around Braulio Carrillo National Park, and held beautiful birds from the outset, like Black-and-yellow Tanager, Black-thighed Grosbeak, and daytime Spectacled and Crested Owls. A tour first was also provided by a Thicket Antpitta seen well by all. From there we continued downslope to the lowlands of that side, and the world famous La Selva Biological Station. La Selva is a place where birds feel particularly plentiful, and we racked up a heady list of birds on our one and a half days there, including Rufous and Broad-billed Motmots, Black-throated Trogon, Pale-billed, Cinnamon and Chestnut-colored Woodpeckers, Keel-billed and Yellow-throated Toucans, and Great Curassow, to name just a few of the highlights, which also included several two-toed sloths, the iconic Red-eyed Tree Frog (photo last page), and Strawberry Poison Dart Frogs of the much publicized “blue jeans” form that adorns so many tourist posters in this Sarapiqui region. -

The Best of Costa Rica March 19–31, 2019

THE BEST OF COSTA RICA MARCH 19–31, 2019 Buffy-crowned Wood-Partridge © David Ascanio LEADERS: DAVID ASCANIO & MAURICIO CHINCHILLA LIST COMPILED BY: DAVID ASCANIO VICTOR EMANUEL NATURE TOURS, INC. 2525 WALLINGWOOD DRIVE, SUITE 1003 AUSTIN, TEXAS 78746 WWW.VENTBIRD.COM THE BEST OF COSTA RICA March 19–31, 2019 By David Ascanio Photo album: https://www.flickr.com/photos/davidascanio/albums/72157706650233041 It’s about 02:00 AM in San José, and we are listening to the widespread and ubiquitous Clay-colored Robin singing outside our hotel windows. Yet, it was still too early to experience the real explosion of bird song, which usually happens after dawn. Then, after 05:30 AM, the chorus started when a vocal Great Kiskadee broke the morning silence, followed by the scratchy notes of two Hoffmann´s Woodpeckers, a nesting pair of Inca Doves, the ascending and monotonous song of the Yellow-bellied Elaenia, and the cacophony of an (apparently!) engaged pair of Rufous-naped Wrens. This was indeed a warm welcome to magical Costa Rica! To complement the first morning of birding, two boreal migrants, Baltimore Orioles and a Tennessee Warbler, joined the bird feast just outside the hotel area. Broad-billed Motmot . Photo: D. Ascanio © Victor Emanuel Nature Tours 2 The Best of Costa Rica, 2019 After breakfast, we drove towards the volcanic ring of Costa Rica. Circling the slope of Poas volcano, we eventually reached the inspiring Bosque de Paz. With its hummingbird feeders and trails transecting a beautiful moss-covered forest, this lodge offered us the opportunity to see one of Costa Rica´s most difficult-to-see Grallaridae, the Scaled Antpitta.